The Hoover Project on China’s Global Sharp Power, Stanford’s Center for East Asian Studies, and Stanford's Department of History presented Sparks: China's Underground Historians and their Battle for the Future on Monday, March 18, 2024 from 4:00 – 5:30 PM PT in Stauffer Auditorium.

Sparks: China's Underground Historians and their Battle for the Future describes how some of China's best-known writers, filmmakers, and artists have overcome crackdowns and censorship to forge a nationwide movement that challenges the Communist Party on its most hallowed ground: its control of history. The past is a battleground in many countries, but in China it is crucial to political power. In traditional China, dynasties rewrote history to justify their rule by proving that their predecessors were unworthy of holding power. Marxism gave this a modern gloss, describing history as an unstoppable force heading toward Communism's triumph. The Chinese Communist Party builds on these ideas to whitewash its misdeeds and glorify its rule. Indeed, one of Xi Jinping's signature policies is the control of history, which he equates with the party's survival. But in recent years, a network of independent writers, artists, and filmmakers have begun challenging this state-led disremembering. Using digital technologies to bypass China's legendary surveillance state, their samizdat journals, guerilla media posts, and underground films document a regular pattern of disasters: from famines and purges of years past to ethnic clashes and virus outbreaks of the present--powerful and inspiring accounts that have underpinned recent protests in China against Xi Jinping's strongman rule. Based on years of first-hand research in Xi Jinping's China, Sparks challenges stereotypes of a China where the state has quashed all free thought, revealing instead a country engaged in one of humanity's great struggles of memory against forgetting—a battle that will shape the China that emerges in the mid-21st century.

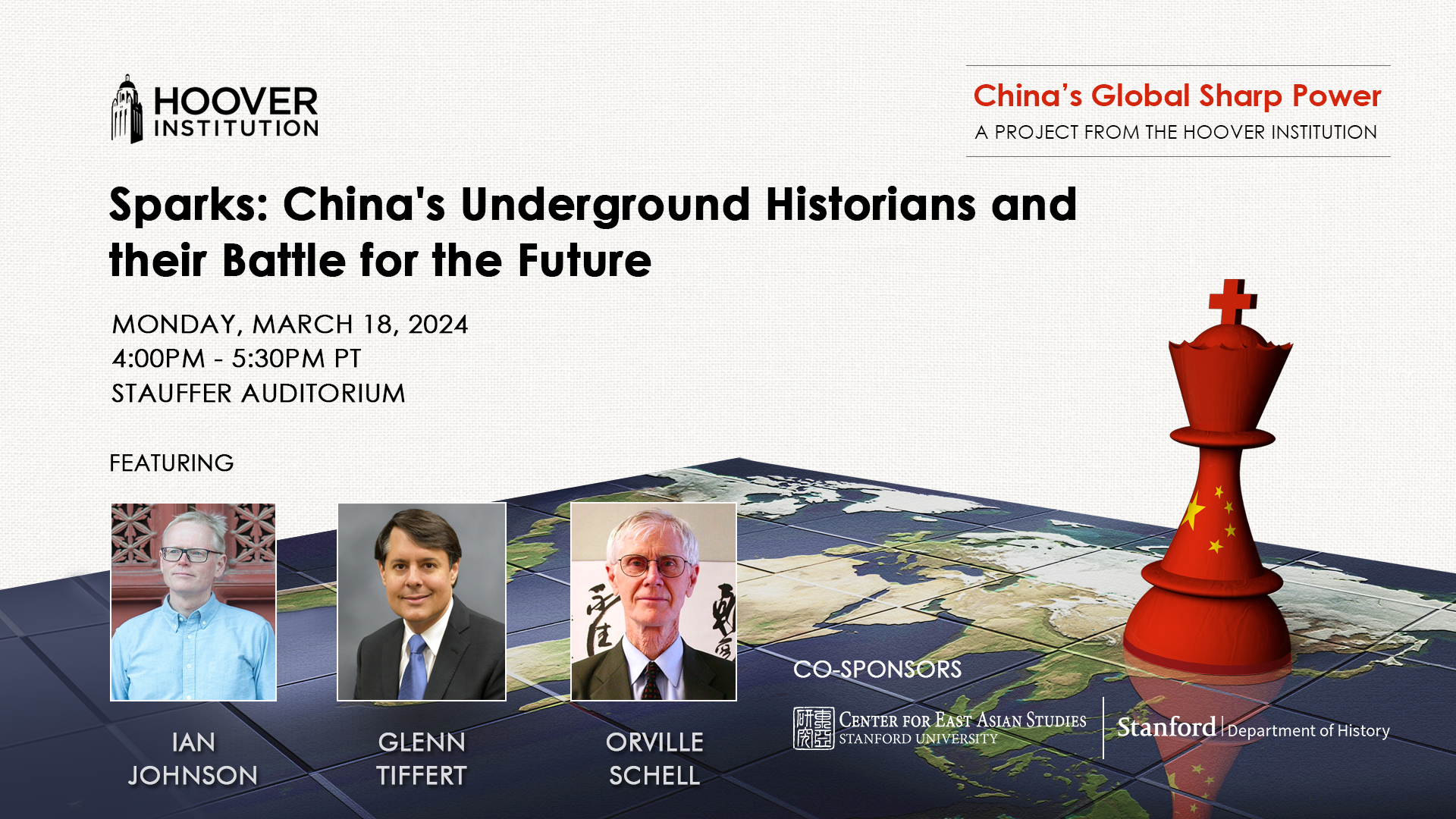

>> Glenn Tiffert: Thank you very much for joining us in our latest installation of the speaker series of the project on China's global sharp power. Today it is my pleasure to introduce Ian Johnson to talk about his new book Sparks, China's underground historians and their battle for the future. Ian Johnson is among the most astute commentators on contemporary China anywhere today.

He is a Stephen Schwartzman senior fellow for China studies at the Council on Foreign and Relations. And a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer who has spent most of his adult career and life working in China as a correspondent for the New York Times, New York Review of Books, and the Wall Street Journal.

He's the author of other books that also focus on the intersection of politics and civil society, including the Souls of China, the return of religion after Mao, and wild three stories of change in modern China. After his presentation, we'll be joined by Orville Schellenheid, who's the Arthur Ross director of the center on US China Relations at the Asia Society in New York.

He's the former professor and dean of the School of Journalism at the University of California, Berkeley, and he's the author of 15 books, 10 of them about China, and a contributor to numerous edited volumes. He's been an invaluable contributor with CGSP on several projects, most recently co-editing the joint study by Hoover and the Asia Society on the competition in semiconductors, silicon triangle.

Please join me in welcoming Ian Johnson. Thank you.

>> Ian Johnson: Thank you very much for the kind introduction. I want to talk a little bit about how I got involved in this project and why I wrote it, and then we'll have a discussion and open the floor to Q&A's.

So calling this the Battle for Memory in China. Briefly, I went back to China. I was in China as a journalist from 1994 to 2001, and I went back around the time of the Olympics with an idea of wanting to write a book on religion in China, which is something I ended up doing.

In 2017, I published a book on the religious revival in China called the Souls of China. And so I spent a lot of time talking to religious believers and their faiths and their hopes and so on and so forth. But at the same time, I was doing a lot of work for the New York Review of Books, and I had a Q&A and a series there with intellectuals that I called talking about China.

You can still find it on the New York Review of Books website. It's paywalled, but thanks to the good folks at the Asia Society, there is a NYRB archive that unpaywalls that. So if you wanna navigate your way, you can find these articles there. One of the very first people I talked to was Yang Jisheng, who is probably one of China's best known unofficial historians.

And he talked to me about, of course, the importance of history. If you know him at all, he wrote a landmark book on the great famine called Tombstone. He also wrote a book on the cultural revolution that came out a couple of years ago called the World Turned Upside Down.

These have been translated into English, they came out earlier in Chinese. And I began to see a similarity between the people who had a spiritual quest and the these public intellectuals I was talking about. They all saw that China was suffering from some sort of authoritarian malaise, that there was some political problem, something wrong in the country.

The people on the spiritual side of things thought that China needed a spiritual revolution before they could actually have a political revolution. And indeed, some of them had been through the 1989 protests, the Tiananmen protests, and the failure of that. They sort of chalked up partly not just to the government being strong, authoritarian, brutal, but also that China needed some kind of a spiritual revolution that had to start from within before it could go out.

But the other people I talked to, and I have some pictures of them here. These were all portraits done of these thinkers. They believed that China had to deal with its history first, that by confronting the whitewashed history, that by challenging the whitewashed history that the party presents, this would cause more of an awakening.

That, of course, as we know from our own countries, history matters a lot here, too, in this country were battling and discussing things from the early 17th century. The centrality of slavery in the founding of the United States. People are still debating things from last century, such as the civil rights movement or abortion, the Roe versus Wade from the 1970s.

So in some ways, it's not surprising that Chinese are also concerned with history. But I would argue that history matters more, and this was in China than even perhaps in this country. And this is something that these people brought home to me. And I'll go back and talk about some of these people in depth.

But the main focus of my book ended up being two of these people in the picture. On the upper left, the independent journalist Jiang Shue, and the, oops, on the auto timer already. And the lower level second from the left, the feminist scholar and documentary filmmaker Ai Xiaoming.

And there are many other people I talk about in my book. But these two people come back over and over again in the book. They sort of take you from the beginning of the book, all the way to the end. So I'm gonna show you just some pictures of places of memory.

This is, so just sort of auto go in the background while I talk a bit about some of the ideas in the book. These pictures are from one particular county in southern China where a massacre took place. And the idea of places of memory, the landscape of memory, geography of memory, is something that really informs my book.

And the book is structured geographically, taking you from one part of China to another. And I have, in between the main chapters, I have places of memory that I go and describe. These are little interpolations between the chapters that I call memory. And they are sometimes a location, such as this county.

Sometimes they're a work of memory, like a book or a film or something like that. That's become central to this battle over history. But getting back to the centrality of it, I think it really matters in China because the Communist Party's legitimacy is essentially based on history. So in its telling, China was laid low in the 19th century, starting with the Opium War, as it went through a century of humiliation.

And it was only in 1949, when the CCP took power that China was put back on its feet again, and they made the country territorially whole. The foreign concessions and almost all the foreign colonies, except for Hong Kong and Macau, were closed down and expelled. The foreigners were all driven away.

Soon after that, China fought the United States to a standstill in the Korean War, which was actually sort of sensational when you thought China had suffered a series of military defeats. So one after another in the 19th and early 20th century, and here it was, obviously with a lot of soviet help, fighting the United States and holding its own.

And then it put the country on the road to prosperity, and this is sort of the mythic story that the CCP tells. And this is not just in the pages of People's Daily or big propaganda venues like that, but it's told in every child's textbook, in every movie.

It's the subtext of every television series. There are tons of television shows about how the Red Army fought the Japanese and how it was the Red Army that did this. And the other thing, people watch this, there's not much choice. The textbooks also tell the story. And like a lot of national myths, there are some elements of truth to it, because China did become territorially whole again in 1949.

It might have happened anyway because it was an era of decolonization and probably would happen anyway. The Korean War was in some ways a real achievement at a terrible cost of human lives. And China was eventually, 30 years later, put on a path to some sort of prosperity.

But in between these things are also, of course, the world's greatest reported famine, with up to 45 million people dying. Endless political campaigns and things that go on up until this century. The battle over history isn't just about stuff that happened last century, but also this century, even a few years ago, such as the COVID lockdowns and the terrible price that some people paid in the second half of those lockdowns.

So the people who challenge this say that the party's monopoly on the past has kind of brainwashed people, and that they have to challenge it, and they challenge it by writing their own versions of the past. They may be memoirs, they may be sophisticated books of history with full academic apparatuses, they may be documentary films, works of art.

There's many different ways to challenge the party on this, but it's become an important movement. I think also it has a real resonance in China. Maybe another point to mention is that history, some people think of it as a religion in China. There are religions in China, right?

Like Taoism, and Buddhism, and Christianity, and Islam, and so on and so forth. But the telling of history is almost like a sacred calling in China. When you look back over the past, some of the great heroes of the past were people who stood up to the emperor and tried to tell the truth about what was happening.

They were banished. And these are stories that all Chinese schoolchildren learn in their textbooks. I mean, you can say even the Dragon Boat Festival, which will be coming up in a couple of months, it's essentially a story of dissent, of a official who tried to tell the king what he should do.

The king didn't listen to him, and so he committed suicide and jumped into the water. And the dragon boats are out there to try to find his corpse or prevent it from being eaten up by fish or something like that. This is the real story of the Dragon Boat Festival.

But it's also the story of China's first great historian, Sima Qian, who stood up for an official who was being scapegoated and was then castrated and expected to commit suicide. But he didn't because he wanted to finish writing China's first great work of history, first macro history. So, this are also interesting things, these are also all the heroes of Chinese culture, right?

These are the good guys. And so when you look back at the Chinese culture, when these historians today, they see themselves in the tradition of these unofficial historians of the past. The people who stood up to the leader, who wasn't listening, and who tried to point out the truth, and they may suffer, but in the end, they're the people who are the heroes of the story.

They're the ones who win. So many of them know that right now we're in a very, very difficult time in China. It's a very strong period of authoritarian control under Xi Jinping, but many of them are still convinced that in the end, they're going to succeed. And I think this is probably the one of the motivating factors for many of them.

They view themselves as undertaking a sacred calling, almost. Many people wanna know, how important are these people? I think one way of looking at it is to look at the government's reaction. And one could argue, in fact, I argue in the book, that since taking power in 2012, Xi Jinping has made the control of history one of his central tasks.

He appeared for the first time in public as head of the party in November of 2012 at the National Museum of China, at his permanent exhibition called the road to rejuvenation, which tells this story, the opium war. There were patriotic Chinese, but they couldn't do anything until the communist party came along and saved China.

And if you go to this exhibition, there's nothing about the great famine, I think there's one picture from the Cultural Revolution, and that's it. It's basically China going from strength to strength to strength over the past, roughly, almost now, 75 years. This will be the 75th anniversary coming up.

So he appeared there, and the next year, 2013, he essentially banned criticism of the Mao era. He called the two negations. You can't negate the Mao era and before the reform era. You can't be against Mao and be for the capitalist style reforms. And vice versa, you can't be against the capital style reforms and be a Maoist.

You have to accept both of them, they're two sides of the same coin. And this was the beginning of a lot of pressure on unofficial historians because up until then, there were reformers in the party who said that, yeah, we want the Communist Party to still run China.

But for us to do that, we need to look at our own history and kind of get that right, make amends for the debacles of the first decades of our rule. There were many people up near the top, such as Mao's personal secretary, Lee Ray, and even Xi's own father, Xi Zhongxun, was a supporter of this liberal trend inside the party.

He was a backer of a magazine called China Through the Ages, or Yanhuang Chunqiu. China Through the Ages published many cutting-edge, interesting works that challenged some of the CCP's orthodoxy and its myth-like telling of history. And they said, well, they never challenged the party's right to rule, but they challenged some of these stories that just really don't hold up.

The one that really got them closed down in 2016 was a story about these Red Army soldiers who fought the Japanese on this mountain outside of Beijing. And when they got to their last bullet, they jumped off this cliff and miraculously survived. And the Japanese were then befuddled because they weren't able to capture the Red Army soldiers.

And so this writer went back and he went to the mountain. He said, if you jumped off this bit, it would be, it's a 2,000 foot drop, you'd die. That can't have been the case, it has to be there's something not quite right here in this story. And so they got sued by family members who were probably put up to the lawsuit by the party.

And then eventually they closed it. And so in 2016, this magazine, which was an official magazine, it wasn't an underground magazine. It was an official one that you could subscribe and get mailed to every month, it was closed down. And this is almost like an act of edible defiance by Xi Jinping, cuz his own dad had supported the magazine.

And in the way that his own dad had been a senior leader in the party, one of the, say, 20 or 30 most influential people in the CCP when the party took power. And after the Cultural Revolution, he supported the founding of this magazine, as leaders do, they give some calligraphy.

And they write a piece of calligraphy, and then you give it to the magazine, it's just like a talisman that you have. And so he wrote this calligraphy that is like which is like, China through the ages is doing a pretty good job. And so they would print this on the back of their magazine.

It's like, see, Xi Zhongxun supported us. But that didn't matter to the son, cuz the son saw this as too threatening, and the magazine had to be closed. You might wonder why. Was it just an oedipal complex or was there something else going on? And I would say, there probably was something else going on, which is that Xi saw the collapse of the Soviet Union as due primarily to an ideological hollowing out of the party.

After the Soviet Union collapsed, the leaders at the time, especially Deng Xiaoping and his handpicked lieutenants, they saw the problem as economic. So that's why soon after that, Deng goes on something called the southern tour to jumpstart reforms again. This is after Tiananmen, the country's in a bit of a deep freeze for a couple of years, but he gets the economy going again.

He pushes pro-reformist leaders kind of to the top. China joins the WTO and does stuff like that. And he thought the problem was economic. And he said, if we dont get the economy right, were gonna go the way of the Soviet Union, where, as you know, there were many lines for consumer goods and stuff like that.

Xi Jinping, I think, sees a different problem, and he's spoken about this explicitly. He said, the problem here is that, it wasn't the perestroika that was the problem of Gorbachev, the economic restructuring. It was the Glasnost, it was the opening up. It was allowing groups like Memorial, which was an independent history-investigating NGO, that literally dug up the graves of the Stalin era and wrote articles about it.

They recently won a Nobel Peace prize and recently Putin closed them down. It's groups like that that were the problem. And he has this line in one of his talks where he said, at the end of the day, nobody was man enough just in the Soviet Union to just track down and say, this is nonsense.

We're not gonna allow this country to collapse. Send out the tanks, what the hell's going on? And so he talks about this very explicitly as a problem. So I think this is why he sees this as so important. And why he sees these kinds of people, we'll show some pictures of here, to be such a challenge to the party.

Some of the people I write about, almost all the people I write about are autodidactic historians. Some of them are academics, but they're not working in their field. Some of them are scientists or they're in other academic disciplines, but they write about history. Some of them are people like this fellow, Tan Hecheng, who was a journalist.

And in the 1980s, during this period, when the party wanted to make amends for the past, he went down to that place where the massacre took place. He went down there as a journalist, an official journalist with a delegation of 1,200 officials to find out why party officials had massacred with their own hands 9,000 people in this county.

And they did this big investigation. They came up with tens of thousands of pages of documents. But when they got back and were ready to publish all this, the winds had already turned against this kind of reformist leader at the time, the guy named Hu Yaobang. And he was not allowed to publish his article.

But he felt that he'd promised this to the people, to the officials he talked to, to the victims. He promised them that he would write something, so that China won't go through this again, this kind of systemic violence caused by the party. And so he made it his life's work.

He just went back there on his vacation. Every summer he'd go back down to the county, he lived in Changsha, which is the provincial capital of Hunan. And he'd go back time and time again, and ended up writing a book that was published in 2016 in Hunan, and it was translated into English as The Killing Wind.

Here I am taking some pictures, this is some of the people he talked to. The other person I mentioned, Jiang Xue, independent journalist who wrote many investigative articles in the 2000s. When Xi began to close down media companies or put in a harder ideological line in the early 2010s, she became an independent journalist and would work for donations.

She would write these articles, these long investigations into the wives of the human rights lawyers. She wrote a very touching series of profiles about that. And she also wrote a long investigation into the famine in her home county. I'll talk a bit about that later. Some of the people I write about, I don't talk about too much, but this is an independent filmmaker named Wang Bing.

Wang Bing is a celebrated arthouse film director. He recently came out with a film that got widely reviewed in the New York Times and so on and so forth about workers. But he also wrote about this labor camp, not wrote about, but he made a film, a couple of films about the Jiabiangou labor camp.

And this is a steal from one of his films. Ai Xiaoming is, as I said, a feminist scholar, independent filmmaker. She went to the University of the South in Tennessee, spent a year there. And came back with a manuscript to The Vagina Monologues, translated it into Chinese, had her students put on this play, and decided, we need to make a documentary film about this.

So she called up her old buddy Hu Jie, who is one of the leading independent documentary filmmakers in China, and said, come down and help me make this documentary film. And so he goes down there with his handheld camera and starts filming it. And she thinks after, well, I could probably do this also.

So he becomes her mentor. They make three or four films together, initially, smaller films, like 45-minute films. One about a very infamous case of a woman who was murdered by her boyfriend. And the case was sort of covered up, and the government kind of excused this date rape and not really important.

And this became a big scandal in China in the 2000s. They made a film about that. And then she went on to make her own films, which were very sophisticated, long films. Her longest and most complex film is also on that labor camp that I mentioned, Jiabiangou labor campus, it's four and a half hours.

People like Ai Xiaoming and like Hu Jie, they, as I said, they're autodidactic, but they're very ambitious people. They dissect the great works of the Holocaust. Shoah, Hotel Terminus, the film directors like Marcel Ophuls, Claude Lanzmann, they go through these films scene by scene and try to figure out, why did they do it like that?

Why did they do the interview? Why was the camera set up like that? The technique which, I think, Ophuls does really well of letting these officials, these guys, just these ex-Nazis, talk and talk and talk until they implicate themselves. Having these long, pregnant silence where the cameras just going, and then they begin to explain what they did.

And, well, it wasn't so bad and it was just a few people I killed, and it goes on and on, gets worse and worse for them. They use those kind of techniques also, and it's really interesting. So they haven't been to film school. Hu Jie also uses art, in a way, to fill in the gaps.

One of the great tragedies is the great famine from 1958 to 62 or 59 to 61, however you want to. And one of the reasons I think that it gets less ink in the west and even in China than say things like the Cultural Revolution, even though ten times more people died in the famine than, say, in the Cultural Revolution, is because there's no visual record.

There is really, if you think of horrific images of famines, you can sort of immediately think of kids with bloated bellies and stuff like that that will come to mind. There's nothing like that. Because in the countryside, in China, in these poor communities, these were illiterate farmers. They had no cameras, they had no equipment like that.

And unlike, say, the Cultural Revolution, which often affected educated people, after it ended, they didn't go back and write memoirs because they were illiterate, mostly. So they couldn't write anything. So we don't have a lot of memoirs, a lot of stories about the famine, and we have almost no visual record of it.

In fact, one of the great tragedies, one of the most outrageous things is in 1959, Henri Cartier-Bresson with Magnum went back to China and did a photo essay. It's on the cover of Life magazine. In fact, I just bought it. It was like July 59 or something like that.

And it shows backyard steel furnaces and all these people doing great things. And it shows some North Korea type things, which you kind of, well, these army of people digging the Miyun reservoir, a dam outside of Beijing. But he doesn't capture the famine at all cuz he wasn't allowed to go there, and he didn't ask any questions, and he just was given this dog and pony show.

But what an opportunity that would have been, but probably impossible for that. So people like Hu Jie, they use art to do that. And of course, Wang Bing, he made a film about it using actors and so on to try to recreate the events of the famine. And this is Hu Jie.

These filmmakers, one thing that's really important to note is they don't take any foreign money. They are low budget, and they don't take foreign money because they know that would be one way for sure to get into trouble. They would then say, foreign forces foreign forces are putting you up to this, and they're behind your work.

So he travels around with his cheap handheld camera and makes these films on his own. Same with Ai Xiaoming. A couple of times, I think, a grad student helped her tote equipment around, but that was basically it. I think maybe the thing I wanted before I finish, I wanna talk about the role of technology and where I would date the beginning of this movement.

There have been people throughout the history of the PRC who have tried to challenge the party's monopoly in the past or their version of events. One of them was this magazine called Spark, and this is what my book gets its name from. It was a magazine published is almost too grand of a word, but it was written by students in 1960.

They had been exiled to the city called Tianshui, and they saw the famine firsthand. And being naive students, they thought, golly gosh, the government can't know about this. Cuz if the government knew what was going on, they'd surely do something. So one of the students was a party member, and he wrote a long letter to the party's theoretical journal, red flags, of explaining what's going on here, mails it off.

A month later, a PLA truck pulls up with soldiers. They string him up, and he has to sort of dangle from a tree with his hands behind his back for hours and hours and hours. The students realize, okay, the party probably does know what's going on, but for some reason, they're not doing anything.

So they got a hold of a mimeograph machine in a local party office, and they hand wrote out this eight-page magazine that they called Spark. From the idiomatic expression in Chinese, a single spark can cause a prairie fire. And it's also an idiomatic expression in English. But anyways, and they wrote, this first one was sort of basically the first.

The articles are really interesting because they talk about things that are relevant today. They talk about the lack of freedom of expression, the fact that this political system can put up leaders who grasp enormous power, and then you have to follow them. Now they're talking about Mao, but you can kinda think of Xi Jinping.

They also talk about things that haven't changed at all, like farmers don't own their land. So this is why the farmers had to follow these insane policies that led to the famine. They didn't own their own land. They couldn't do what they wanted on their land. So all property, every square inch of China, belongs to the state, that hasn't changed.

So anyway, these students wrote this thing, as you can imagine, a few months later, they all get rounded up. 40 people get arrested. Three of them are executed. The guy in the center was the founder of Zheng Shunyuan. That's a picture of him shortly after serving in the army.

He was a bit older than the other students. That's a picture of him on the left shortly before his execution. On the right, the poet Lin Zhao, who contributed poems to the journal. She was also arrested and later executed in 1970. By the way, just as a quick aside, there's a dynamite book about her called Blood Letters by the Duke University Professor Lian Xi, which talks about her life.

She was a christian dissident and was motivated very much by faith and wrote these amazing sort of long, epic poems that the students found electrifying, in fact, inspired them. Like many other, this magazine was then confiscated. Nobody heard of it until the late 1980s, when one of the students, a woman who had been sent to a labor camp for 18 years, was then released.

She eventually went back, and when she was able to look into something called her personnel file, which is something that almost all Chinese people have. It can have banal things like your high school test scores or something like that, but it would have your police records in it.

She was able to sit down with her personal file and photograph all 500 pages of it. It had all the confessions of all the students. It had all the copies of the two issues of Spark. It had even, I've got a picture, her love letters that she wrote to Zheng Shunyuan, the guy who founded it, who was executed.

They kept everything, the way, I would say, the more polite way, the way that retentive bureaucracy does. They can't throw away anything, right? If you're a police officer, these are enemies of the state. You're not gonna dare throw away anything. So it was all kept in the file, and she took photos of it.

It sat in her apartment in Shanghai for a few years until the late 1990s when this new technology, newish technology, began to spread in China, the PDF. And we take this totally for granted. But obviously with the PDF, if you have the photos, you can then recreate the magazine.

So the magazine was then put together. In fact, all of these, all 500 pages were put into PDF's, and they began to circulate among Chinese people in the late 1990s, they had this electrifying effect on people. One of the most prominent public intellectuals in China, Xue Wei Ping.

She said, now we have our genealogy. Now we know there were people 30 years earlier grappling with the same issue, lack of freedom of expression. And they wrote these powerful essays. So the PDF allows you to recreate lost books, journals and things like that, letters, but it also allows you to self publish.

And it's at this time in the late 1990s that these big underground journals began to publish, like Yesterday, Zhou Tian or Remembrance, GE, and they are self published. These are not like that other magazine I mentioned, China through the ages, which was an official publication and printed, and you could buy and so on and so forth.

These are circulated only by email to friends, and they would be then sent on further and further. The other big technological breakthrough. We'll go back to Cheng Shu later perhaps. And this is Hujie again, I mentioned the digital camera. Sounds so obvious, right? But in the late, if you think 30, 40 years ago, if you wanted to make a documentary film, it was a big project.

You had to have expensive, sophisticated equipment. But by the late 90s and early 2000s, people were making films in China with digital cameras. And it meant anybody could make a film and edit it on their laptop. They didn't need editing equipment. So this started this genre of underground history films, of which there are at least 200.

And this is the kind of film that Hujie made. Again, it's kind of low res, purposefully, almost like as a badge of honor, cuz in China, the best equipped people are the propagandists. The government has armies of people doing propaganda. They have the latest equipment, the best equipment.

They're trained, they go abroad to study and go back and make sophisticated, slick films on this, that or the other thing. But these people are like, no, no, no. We have the crappy equipment. We do the stuff that's handheld, we purposefully, it's like jerky. It's like, can you buy a tripod?

No, I wanted to make it and I want it to look real. I wanted to have this feeling of reality. So they make these kind of films. This is Ai Xiaoming with her lousy camera. Even I asked Hujie later, I said, why don't you buy a better camera?

You're still using this 15 year old thing. And he's, why should I bother? I said, well, it'll be better resolution, it'll be 4K. Nah, an iPhone 14 definitely has a better camera than you have. And he's like, well, it doesn't matter to them. This is not their goal is to have some slick thing.

I think it's also worth pointing out that this, I don't wanna go too long, but this desire to look into the past isn't limited to just a few intellectuals in big cities. I think there are really hundreds and hundreds of people working on this. I participated in a couple of workshops that I describe in the book where people from around the country would go to the media university in Beijing for workshops on how to use cameras.

And they didn't all have a big political agenda, right? It was sometimes they just wanna make a film about what grandma and grandpa experienced, and they would learn how to put a lapel mic on and how to use a digital camera and edit it and some basic interviewing techniques.

But many times people would go back and begin to ask these questions and come up with revealing things like, there was this famine. I didn't know that. And so on and so forth. So it's sort of a bigger movement. I think it also is worth pointing out it involves even recent events like the COVID lockdowns in Shanghai.

There are many independent journalists who wrote stuff about that. There are people who are writing books and articles about this now. Yeah, well, I won't go through all this. This is the white paper protest from a year and a half ago. Yeah, let me just briefly say future trends before I end it.

I think a lot of this was due to, hang on a second. Let me go to that later. This is a picture from a book warehouse in Hong Kong. A lot of these books used to be published in Hong Kong and then were smuggled back into China. The government began to stop that about ten years ago when they began x raying suitcases.

When you came back from Hong Kong, you had to have your suitcase x rayed. And if they found books, they would confiscate them cuz people were going to these independent bookstores, they closed down the bookstores. And a couple of years ago, I wrote about this also in the book, one of the better known independent publishers in Hong Kong.

He called me up and he said, the warehouse owners, they can't sell the books in the bookstores, but the warehouse owners think they're gonna violate the new national security law if they even hold these books. We organized this kind of rescue operation to get some of the books out of China and into libraries and stuff like that.

But I think that the trend is that there are more and more people abroad who are active in some of these things. I think there's something, I've noticed that there's a lot more interaction between, especially young people inside and outside China in a way that I don't feel was true, say, ten years ago.

I mean, people say, well, there's the Internet and stuff, but there was the Internet ten years ago. But I think that right now in China, for people who are, say, under 40, what China's going through now is one of the first major kind of crises or question marks that they've been through.

Many of them under 40 would not have experienced Tiananmen, and they would have experienced the 90s and 2000s when things are kind of getting better and better, and there may be problems like the Falun Gong crackdown and so on. But overall, tomorrow was kind of a better day, and it was better maybe not to rock the boat.

But the debacle of the last half of the COVID lockdowns, the slowing economy and things like that. Xi Jinping taking a third term has caused many people to think there's something not right in the country. I can't even live a quasi normal life in China anymore. Or I can't take for granted that I can just put my head down and make money because the economy is not even good.

So I think this is driving more and more young people to link up. I've noticed there's more people, younger people, inside and outside China, who are active and working together as a quick promotion at the very end here, people often want to know, where can I find some of this stuff?

Where can I see it? Where can I find the movies? I set up this charitable organization, a 501(c)(3) called the China Unofficial Archives. This is just a screenshot of the homepage. It's a fully bilingual site. It's aimed primarily at Chinese people, but English being the international language of scholarship, the pages are also in English, where we post books, magazines, and movies.

Right now we have several, we have over 800 items there. We're rejiggering the software. We launched it on December 11th, but we had some feedback from people who said, you should really put this on a database software that would allow us to do full text searches and so on and so forth.

So we're going to migrate the site to that. But any case, it's still active. And if you go into the explore the collection, you can see all these things that we have books, some talking about 1959 in Lhasa and so on and so forth. This is an example of, one of the books that you can download is English there and then Chinese, and then there's a full PDF download of the book that you can get.

So it's aimed to kind of make this more accessible. For me, it's really aimed at people inside China. Of course, the site is blocked in China but many people have VPN's and they can access it. So it's a way if you know, you like Ai Xiaoming but you didn't realize you made these other films you can click on Ai Xiaoming.

You can search the archive very quickly by creator or by theme or by year, and you can find other works on the great famine or whatnot, and then you can find things. But I think also for foreigners, it's worth seeing how much has been made. It's not just Yang Jisheng writing a couple of books and a couple of other people writing a couple of books.

It's hundreds and hundreds of books, these magazines that are still being published, films, hundreds of films that have been made. I think it's worth taking note of that, because for some reason, in our mental mind, we used to be. When I was growing up, people were also aware of dissidents and so on behind the Iron Curtain in the Cold War.

People aren't so aware of these people, I don't think, in China. And so this is my effort to kind of say this in the conclusion of the book to inspire civil society to bring more of these people over here, bring it to film festivals, have a film festival dedicated to Hu Jie or something like that.

It hasn't been done. Those kind of things, I think, would be, even if they can't leave China, it would be huge. It's unbelievable, these people want to be written about. Yes, they want be written about. They don't wanna be forgotten. They want their works out there, they want people abroad.

So otherwise, it's a very lonely job doing something like that. You want to know that other people care. And I think that that's something that we can do here abroad to help them. So with that, I'll stop and thank you very much.

>> Glenn Tiffert: So the next part of our program involves a discussion between Orville and Ian, and then we'll open it up for audience Q&A.

>> Orville Schell: Well, Sparks, congratulations. I mean, this is a really wonderful evocation of that part of China which is so difficult to see beneath the carefully manicured surface of party propaganda. And moreover, I would say that I think Ian's done an unusual job in personifying these sort of different kinds of oppositional voices within actual characters.

And it reminds us that there are people who do care and that there is a kind of a subterranean aquifer that has existed throughout history of these people. But, Ian, let me ask you this.

>> Orville Schell: There have been people since time immemorial who care about the correctness of history, who care about humanism, care about a lot of august things.

Do you think that in China's case, we've reached some inflection point in history where autocracy united with technology creates some kind of new system in force that may mean these people are forever doomed to being marginal, submerged. And people like you can dig them out, but that they may ultimately, in the grand sweep of historical evolution, be not particularly consequential?

>> Ian Johnson: Yeah, it's possible. The pessimistic view is that things will never change. I remember when I went to Germany in 1988 and I went to East Germany, and the conventional wisdom then is East Germany will never change. It's the most Stalinist, the hardest line, etc., etc. I traveled around East Germany, and a year and a half later, the country didn't exist.

And that's not gonna happen in China, that was pretty special series of-

>> Orville Schell: And it gave hope to the dream that things do end, countries do turn over.

>> Ian Johnson: Yeah, the end of history or something like that. Yeah, but Vaclav Havel had this great saying in 1986. He said, the face that a country presents the world now isn't the face that it will always have.

The potential inside of people are, I can't remember what he said, hard to fathom or hard to predict. And so I think we often have this linear projection of things. The way things are now is the way they're always gonna be, right? But it's also possible that Xi Jinping's maybe this is the optimistic scenario.

Xi Jinping stays in power for another ten years, the economy continues to go south. China doesn't make the leap to the advanced countries because of all these various problems. The economy, the per capita GDP doesn't go up the way they want it to go. And when he dies, and he will die one day, the party will have one of its big corrections, which it had after the Cultural Revolution.

And they say, you know what? That path just didn't quite work the way we thought it was gonna work, and we need somebody who's more of a reformist and that could then change things. It may not, they may just bring in another Xi Jinping, who is even harder line scenario.

But you can't entirely rule out some kind of shame.

>> Orville Schell: Yeah, I think that's well said. I mean, I remember being in China in the 1970s when Mao Zedong was still alive and the Cultural Revolution was still going. And one had absolutely no sense of any incipient capacity of the country to be other than it was.

And it seemed that this was China, and yet a year later, Mao died, Deng Xiaoping came to power. You all know the litany that what happened after that. And it was a reminder that then that some of the forces that I think you're writing about here that were even present, although unseen during that period, did sum well up with incredible vigor in the 1980s.

>> Ian Johnson: Yeah.

>> Orville Schell: So, I mean, these forces are ongoing. You describe them now as perhaps even more evolved and more fulsome as a result of our globalized world than they would have been back then when people didn't have such easy ability to communicate digitally and whatnot. Do you think that now, as you look at the manicured surface, the forces underneath are more powerful will prove to be more able to re-express themselves in a fulsome way should the worm turn?

>> Ian Johnson: I think many of the people I write about in the book are quite realistic. One of the people said, it's like a message in the bottle to future generations. We want future generations to know that there were still people now in Xi Jinping's China who were trying to do things, and they also are trying to just do oral histories to get stuff on the record so that future generations will have this material.

I think it's harder to erase that, like Spark, the magazine. If it hadn't been for these digital technologies, the party had erased it. I mean, nobody knew about the magazine, Spark, in the 60s and 70s.

>> Orville Schell: It came from this godforsaken place, Tianshui, heavenly water, which was hardly heavenly.

I mean, I was quite surprised that that was sort of an epicenter of something of some of this.

>> Ian Johnson: Well, I know people from Tianshui, and they would disagree. But it's actually got these amazing Buddhist grottoes in Tianshui. But yeah, it's true, but these were students who had been caught up in the anti-rightist campaign.

They were at Lanzhou University and they had ventured criticisms of the party and the Hundred Flowers Movement. This is another in this earlier thing, in what was it, 56 or 57. And then they were then all sent off to the countryside. So that's why you had these remarkable, intelligent people.

And the funny thing, the reason they got a hold of the mimeograph machine is the local officials thought, this is a godsend. We have 20 educated people. And so they set up an online, not an online survey, but a community college for farmers to teach them literacy. So they had the students they gave them.

That's why they got into the party office, cuz they use the party office, and they were reading the newspapers. They also realized the famine was more than just in Tianshui or in Gansu. It was all across the country, because they were reading various things. Things they heard about Peng Dihuai at the Lushan conference, and they put two together and so on.

But they got this mimeograph machine because of that. So, yeah, I think generally, the feeling today by people is that they know this isn't gonna be widely read, it's not gonna be widely seen. It's not gonna be on public television or something like that in China, but maybe someday in the future it will be.

>> Orville Schell: I mean, I think we sort of blithely assume in this day and age that there is a fundamental drive towards freedom and openness that animates all human beings. But, I mean, if we look at history, it is not actually the case. And I would say particularly Chinese history, which largely had very autocratic imperial regimes since the time immemorial.

>> Ian Johnson: Well, so do most countries. I mean, you look at many countries in the EU today, like Spain. I mean, Spain was run by a fascist dictator until the 1970s. Portugal, these are not like eternal democracies. Greece was the cradle of democracy or something like that, was run by military junta until pretty late.

These countries only democratized fairly recently. So Germany doesn't have a great history of democracy. Only in the past, say, 75 years. So, yeah, I mean, China could. I don't think any of these people have this idea they want Westminster democracy or something like that. They just want a more open China where you can talk about things.

I don't know, I think probably if you had, all of a sudden the party lifted the lid on this, you'd have a lot of different opinions, and you'd have many people who would even be supporting the party if they could. If there were election the party might well win, or they might think it'd be even maybe even more nationalistic.

So it's hard to know how things will go in the future.

>> Orville Schell: So let's for a minute, analyze the party's perspective, which is, if they release these control mechanisms and you have all these voices speaking out. You'll have cacophony and quickly you'll have chaos. How do you answer that?

Do you think that China could survive a real opening up in democratization?

>> Ian Johnson: Well, Chinese society, Taiwan has shown that it's possible.

>> Orville Schell: Small island with-.

>> Ian Johnson: And very specific historical circumstances. But, there was this hope, dream, maybe delusion in the 1990s that these rural elections, they had some senior leaders in the party would have, this village council would have like five members of it, and they would allow seven candidates or something like that so people could vote.

And if there was really a corrupt person in there, you could vote them out. And the party saw this as a safety valve mechanism. And if there were non party members who were elected, they would quickly recruit them into the party. Yeah, you wanna recruit into the party.

And there was an experiment to bring this up. It was in Sichuan, wasn't the county level, this is a township level. So it was gonna go up from the village to the township. And this was an experiment. It only happened once and the whole thing was closed down.

And now the village elections are basically meaningless. But you could see where over time, that could be something that would happen, that could be reintroduced. And slowly but surely you can get people used to this idea.

>> Orville Schell: You remember that even the Carter center had a whole program to work with these village elections.

And then Xi Jinping came along and Jimmy Carter went to China and he was told that will be the end of the village election program for the Carter center. Why don't you do something else like-

>> Ian Johnson: Build houses.

>> Orville Schell: Economic development, well, that was the end of that.

So in your view, I assume from what you've written not only in this book, but other books, that the party is probably correct from its point of view, that these tendencies would be its demise. And the party understands, and this is why it attacked reform and ended the reform movement, thought that this would be its death metal.

It would reform it out of existence. Do you think they're correct in that assessment?

>> Ian Johnson: Well, it would weaken their. So part of the story is that they have, they tell this mythic founding of the PRC and that they did all these great things, but they have to engage in performance legitimacy.

So the reason why are we still running the country? Okay, you did a great job in 49. Why are you still running the country? Why is Xi Jinping get a third term? So you always have to constantly legitimize yourself by saying what a great job you've done. And so this is why they don't allow.

This is why history isn't just a matter of stuff from last century. It's also a matter of the COVID lockdowns, how that is discussed or not discussed. The economy, the youth unemployment, the 20% youth unemployment and all those statistics have vanished. They have to constantly fight this battle to control history.

It's not just sort of shut down some discussion of the cultural revolution or something like that. So I do think-

>> Orville Schell: They're so incapable of tolerating any sweet disorder in the dress, I mean, any little imperfection. Why is it so important to them to.

>> Ian Johnson: I think there were periods in the past when even under Mao, in the 40s and so on, they would have these internal reference journals that were quite critical, so they would have these.

What was it called? I can't remember, I just saw a panel of it at the AE's meeting. But it was quite amazing the kind of stuff they discussed. And Mao saw this as an important feedback mechanism. But then I think, a lot of leaders, it's like, well, that's enough feedback.

I get the picture, but enough of that. So they can't really tolerate, I mean, there were people like Liu Binyan who wrote articles that expose malfeasance. Not to challenge the CCP's right to rule, but just to sort of show that there are some bad apples. And that was tolerated at various times, but now I think they're just too brittle.

I don't think Xi Jinping is also, he doesn't strike me as a terribly innovative, deep thinking kind of person. He's just sort of a bit of a control freak. And he just doesn't seem to really get economic policy.

>> Orville Schell: Well, he came of age during the Mao era.

>> Ian Johnson: He has no education beyond elementary.

>> Orville Schell: That's where he got his toolkit and didn't go abroad. So, I mean, I think there's somewhat limited in his.

>> Ian Johnson: Well, it's interesting cuz some people think of it as the worst generation. Because they were the people, unlike his predecessors, who all, to some degree, either went abroad to study as kids, even Hu Jintao, I think, studied in a missionary school.

And so did Jiang Zemin, and Jiang Zemin went to the Soviet Union, and Deng Xiaoping, of course, went to France and so on. They've seen at least some of the world and had different perspectives on their life. Xi Jinping hasn't. I mean, he was born in, what? 52, right?

And so his education was interrupted by the cultural revolution. He never really went back to school. He went to, nominally, he has something like a PhD or something. They had this worker peasant soldier university thing. Well, I think that might be the equivalent of a really crappy community college or something like that.

But it doesn't mean he's stupid or something like that. But it just means he hasn't seen much of the world. He's just his whole reference point is the party and the internal political battles of the party. And his dad's experience, cuz his father was felled by history. His father was a senior leader in the party, and he was purged because of a historical novel that was written about the Yenan period.

And his Mao saw this as a threat, because this guy that in the historical novel was actually maybe had ideas before Mao on using farmers to fight and using these guerrilla tactics. And Xi's father had given interviews to the novelist and given him information. And so it wasn't a small purge, like 20,000 people were purged.

So Xi's father was found, so that may be also why she. This is the world he lives in, this is all he knows.

>> Orville Schell: And I think to have had a father who is a counter revolutionary when you grow up at that age is incredibly damaging, informative. And I think probably had a very profound influence on his own sense that to prevail, he had to be more red than anyone else or he would be pilloried because of his father.

Let me ask you finally, people often say that, yes, intellectuals in China are kind of an independent lot. But by and large, most people in China are patriotic, they're nationalistic, and they feel fine with a guy like Xi Jinping. How do you analyze that? And what's your response to that repose to your book?

>> Ian Johnson: Well, I think maybe two things, one is that, it's very hard to know what public opinion is in China or in any country, what people really think. I do think when I was in China up until 2020, when I was expelled and I left, I went back last May, but I had a project for this next book.

I'm working on a working class pilgrimage groups in China. I was dealing with a lot of working class people in Beijing, and they liked Xi Jinping. They thought Xi Jinping has a deep, gravelly kind of voice, and he has this famous singing wife as a superstar. It's like, I don't know what she's like.

>> Orville Schell: Doesn't she sing in the People's Liberation Army?

>> Ian Johnson: Army, yeah, they have a great, great rock group, and she's like that. But she was a patriotic singer, and so they kind of liked him, I think. And the economy is going fine, everything was going good. I went back in May, and the attitude among those people, this is super anecdotal, right?

But it was quite different. Many people had died when the COVID policies were all of a sudden lifted, overnight with no preparation. And many of these old elderly people in the pilgrimage associations die in that period, especially more like December to January or February. And people were just rolling their eyes a little bit.

That doesn't mean they don't like him. But whether people matter or not, change in any society starts with small groups of people. It's a truism like most people in every society don't care about anything. And you can go on, and most American high school students can't find Alaska on a map or whatever.

You can go on and find all these sort of things. It's just like when they go to one of these tropes that foreign journalists will sometimes do on June 4th is, they used to go to a campus and show a picture of pink man, the guy who's sit in front of the tank.

And people were, well, who's that? I don't know, or something like that, or run away. And then the conclusion would be, most young people don't know anything about the Tiananmen Square massacre, which is probably true, or they don't wanna talk about it or something like that. But I think that's kind of true, I mean, probably most young people in the United States think the United States won the Vietnam War or something like that, I think.

Who knows what the people think? Most people don't know much of, I think so. So I don't wanna be pessimistic, but I think that change does start with small groups of people. And these people may have an impact or not, but they are trying to keep the flame alive for a future China when things might be better.

>> Orville Schell: I mean, there is a tradition, I think, over the last 100 years plus in China that intellectuals matter. I mean, from the May 4th movement on down, and that since they are the reincarnation of the scholarly elite of the imperial times, they are of consequence. So in that regard, I think the party may pay particular attention to them.

But do you think there is the capacity in the future for these people to be reborn again if given an opportunity? And how do you look at the future of China in terms of the ability to really rejuvenate not Xi Jinping, but all of division in these people?

>> Ian Johnson: As a journalist, I was hated to predict the future.

>> Orville Schell: You must have some hope.

>> Ian Johnson: Yeah, well, I have hope that there are still people. Jeremy Barmet calls them the other China. Right, he has a series of articles and profiles about that. And it is important to remember that there are people like this in China.

And when people talk about how to engage with China or not to engage with China. I think if you want to engage with China, these would be the people to engage with organizing the secretary of state's visit to Beijing or something like that. I would put in requests to see some of these people, even if you can't see them, the fact you put in the request is a signal.

>> Orville Schell: Of course, that would be lights out for these people.

>> Glenn Tiffert: I don't think so.

>> Ian Johnson: No, I think it'd be helpful. I think it would probably be helpful.

>> Orville Schell: Well, it could work either way, it could protect them or really harm. So since you raised the larger question of geopolitics just before we open it up to the floor, how do you think all of this and Xi Jinping portends for the US China relationship?

>> Ian Johnson: Well, it's not good, putting it mildly. I think the main thing for the United States is probably to get its own house in order and to try to have a more functional political system where everyone isn't always at each other's throats. And I think that would allow us with more self confidence to face China, cuz I think that I sense almost like this real lack of self confidence.

When I work at the Council on Foreign Relations and sometimes go to Washington and brief members of Congress or staffers and stuff like that. People have this almost like paranoid view that China is this giant, this behemoth, and that it's almost this view people had of the Soviet Union, say, in the 1960s, that it's gonna eat our lunch.

It's got this, it's got that they have people up in space before we do and so on and so forth, and they don't realize that China has huge structural problems. And it's not that it's gonna collapse. It doesn't have to be the other extreme, but that it's the country that we should view as a challenge.

And there are areas that we should address, we shouldn't be selling them the rope that they try to use to hang us with. So technology and stuff like that, some technology controls make sense, but we should also not be so paranoid about it. I think there's almost like this idea.

I talked to some people, staffers, and I said, one of the things that bothers worries me the most is that there's only a few hundred Americans studying in China. That we have a whole new generation of Americans, American China watchers, who've never been to China. And I think this is a real problem.

And I said, one of the problems is that they can't get security clearances if they've been to China. And this guy was like, yeah, you're right, they shouldn't get a security.

>> Orville Schell: Or they can't get into China.

>> Ian Johnson: Or yeah, they might not be able to get into China, but I mean, he thought it was fine that you shouldn't get a security clearance, you've been to China.

I'm like, well, this is crazy, you're not gonna have any China experts in the government who've been to China. I mean, is that really what you want, guys? Yeah, yeah, cuz they could all be compromised. Well, they could be turned by the communist party here in the United States also, right?

I mean, this is like an insane view, I think, but this is how we're so nervous about just any touching. This country is gonna poison us and contaminate us. We should be encouraging people to go study there.

>> Orville Schell: Well, there certainly are a lot of imponderables within China, as your book suggests.

And also a lot of imponderables between the outside world and China, which we will just have to wait and see how they resolve. Well, let's.

>> Glenn Tiffert: Yeah, so before we open up to the audience, I wanna take the moderator's prerogative here and ask the first question. You began your talk by noting that your study of chinese religion, which, by the way, was just fabulous, there were very few people who were taking that subject seriously, writing for a broader audience the way that you were.

And so I thank you for that. But saying that that is what tipped you off, that there was something about history that was special that needed to be surfaced. And I wanna pull on that thread for a second because there are those who believe that, of course, history is subjective in the eyes of whoever writes it, but that history in China is pulling on a really different tradition that goes back thousands of years that is different than the western tradition.

And so when we speak about history here at Stanford University, and we speak about history outside of the most August academic departments in China, perhaps we're not talking about the same sort of thing. And that, I think, may get to why history is so loaded in China, apart from the fact that the party claims to have sole authority over it and be obeying the sort of marxist laws of history, which move only in one direction.

And that is that, history has always had an exceptionally strong moral dimension in China. The entire Confucian tradition for 2,000 years was about returning to the glorious dynasty, right? And so history, and the way each successive dynasty wrote history was always to pass judgment on the failures of the previous dynasty in order to legitimate the current dynasty.

And this, of course, the party inherited this tradition and then sort of repackaged it in the bottle of socialist realism, recreating the world as it should be rather than what it is. And caricaturing the past and traditionalism and even the republican past. And having taught many students from the PRC who arrive in american universities, their understanding of what history is, is still informed by the sense of, there has to be a bad guy, there has to be a good guy.

The mission of many of the individuals that I've spoken to, the filmmakers, some of the same people that you've documented, they're driven by a really personal, intense sense of justice. Sometimes it's a promise they made to someone who died in the family, for example, right? For them, this is a mission that I think connects with the religious idea that you spoke about, which is why they persevere in spite of all of the obstacles and adversity in their path.

Do you think, though, that the burden of history, having to find good guys and bad guys, is part of the challenge here in overcoming that? Which is why the party feels it must stamp it out, because any independent history is bound to pass judgment on the party rather than just enhanced understanding.

>> Ian Johnson: Yeah, I think there's part of that. I think that for sure, history, one dynasty would write the previous dynasty's history, and they would say it started out okay, but then problems occurred and it fell and that they lost mandate of heaven. And that's why we had to take over.

And this is essentially what the PRC says also. They will even give the KMT some credit, perhaps, for early on, even now, they give the KMT some credit for fighting the Japanese. I think that's now more acceptable to talk about that. But I think what motivates a lot of the people is the sense of justice.

And I remember talking to one of the people popular in the film and in the book, named Tiger Temple, who is sort of known to Guerre. I asked him, why are you doing this? Is it for this reason or for that reason? And then he says, I don't have a lot of education.

He says, I'm motivated by one thing, E, this concept of E, justice, righteousness. If I see something wrong, I just feel I have to do something about it. And I think there's people like that in every society, right? Most people will get along and go along with stuff, but there are some people who just have this idea that I have to stand up and say something.

And yeah, those people are not writing favorable things about the government. The works are not all diatribes against the CCP, right? They may not be the most sophisticated historical works, but they tend to be, a lot of them are oral histories. A lot of the works that I talk about, our oral histories.

Some of them are fairly sophisticated works like Gaohua, the famous historian from Nanjing University. I mean, his work on the yen, and period, this crucible for the party in the 1940s, it is pretty critical of Mao and is pretty fixated on Mao, but it's really well documented and it's got a fairly sober tone to it.

So same with Yang Jishang and his work on the famine. It's critical of the party and the authoritarian system, but it's, in some ways, pretty fair. I think it matches what other historians outside of China like Frank Decatur, have done in terms of their-

>> Bobby Shore: Hi, I'm Bobby Shore, Center for East Asian Studies graduate student.

Zeroing in on your book, so you talked about that most of their work is censored within China, and that implies that the government or party institutions are aware of their work in order to then censor it. But at least there was no mention that any of these people are in jail or have actually been really cracked down on.

So I'm curious, what is the relationship between these people in your book and various institutions in the party, in the state? Are they being pestered by the government? Are they being threatened? Just what is that relationship between these people and the government?

>> Ian Johnson: Yeah, the way the government handles most, cracking down the most dissent is they crack down on the best-known people first and the people who've done more things, so they get their heavier presence.

I think the government's overall view is, as long as they block them on social media and the Internet, as long as they can't show their films or write about their works, say, on WeChat or Weibo, that that means that they are kind of irrelevant to most Chinese. So much Chinese don't know about this, and that that's kind of good enough.

Some of the people have been given travel bans. Like, AI Xiaoming has not been allowed to leave China, I think she was told recently until 2032, very specific timeframe. And probably in 2032, they'll extend it another ten years or something like that. Hu Jie, the filmmaker, he often has the problem nowadays where he will arrange to go to see somebody, and he goes to their home.

And then he knocks on the door, they open it and say, it's not convenient to talk and they close the door in his face. And this is clearly somebody has talked to them and said, hey, if you want your daughter to go to college or if you want your kid to do this or that, you better not talk to this guy, Hu Jie.

So he faces harassment like that. Other people are still able to do work. Journals are still being published. Some of these underground journals are still being published, and so on. So I guess it's hard to know because it's sort of like the government can't control everything all the time, it can control things.

It's still very labor intensive, I mean, technology can do certain things and it probably will do more things in the future, but right now, the surveillance, it costs a lot of money. And a lot of this is pushed down to the local So there's one guy I write about in the book who ran one of these journals, and he's now sort of retired and has his cafe on the outskirts of Chengdu.

And he estimates there's eight full time cops who are watching his cafe that he runs. And this is not sometimes have this idea. It's all this mega ministry called the Ministry of Public Security. And they have a gazillion officials and they send them down to the outskirts of Chengdu.

No, it's the local police office in the outskirts of Chengdu which has to do this. And the local police chief has got, other stuff going on, there's maybe unrest or there's this or that, and the other thing he's gotta watch out for. And this is a big burden.

And so when I went to visit him, there wasn't anybody there. And they sort of showed up after a while in the late afternoon and say, hey, what's going on? How are you? Okay, it's just the old guy at the edge of town. It's well, and it's also a huge financial burden.

So it's not the government. So for really famous people, they can arrest them or they can survey them to the point that they can't do any work. But for many of the others, I think it's just not quite feasible, but could get more and more. And I think one of the things I sort of mentioned in the book that one of the things this could do is it pushes.

It's a big burden on the state, all of this public security apparatus, the money that they spent on it. There's many other huge priorities. If I think rural education or something like that where they ought to be putting money in for China to make the leap to a high income country.

They've got real social issues they need to deal with, but they're wasting all this money on public security. In some ways, it reminds me of East Germany, which had this huge burden of supporting the Stasi. And China is much more economically vibrant than East Germany. It can afford it right now, but at some point, it is a zero sum game, the money they spend.

>> Speaker 5: Last year I made friends with a young graduate student from the PRC working at the Uber archives. And I'm still in contact with him, but I'm concerned about what I'm sending him or what to send him controversial articles and what I write to him. I was wondering if you could give me some advice, please.

>> Ian Johnson: Well, but I don't know what kind of sensitive stuff you're sending him. But I would try to use some kind of a secure messaging app, like Signal or something like that if you're in contact with people. Cuz email can be read, right? And WeChat is essentially like you're sending a copy of whatever you're doing to the public security bureau.

So those things, if you're just talking about run of the mill stuff, it's fine.

>> Orville Schell: And it's worth noting, Ian, that people who are in this country who evince errant tendencies tend to have their parents or their relatives visited in China. So the potential to control is not limited to China itself now it's limited to the globe.

>> Glenn Tiffert: I think the prudent thing to do is to assume that all that comes could be read by the authorities. Yes, and so sure that just for the safety of the individual may err on the side of caution.

>> Speaker 6: Hi, I was just Googling the speakers and Professor Xiao, because you mentioned AI Xiaoming, and I looked at Ai Xiaoming's mother, who has a family from the warlord Tang Sheng Chi.

The reason I mentioned all this was I've been thinking about the generational difference. When we were growing up in 1976, right after the opening of the country, Professor Xiao must have seen it. The people who wrote books and wrote these dissent disagreeing articles are people who grew up or educated in the Republic of China.

Before I draw a line, exactly the year you were born, 1940. Because they were after they already finished elementary school at 1949. So my concern was they went back after they studied here, like my great grandparents, to China to do a lot of industry as well as education.

But people like us are not going back, and the only people who are going back are making huge amount of money in private equity. So I was just wondering if that is a pessimistic outlook because of that. Because we're all afraid to go back. I was afraid to go back, I did, to try to make contribution to education.

But I can't anymore because we can't even donate to some rural kids because they say, you are foreign influence. So that, why do you donate money to this girl who needs high school? You must have ulterior motives. So it's more a question, I guess, whether you see it being also a reason to be pessimistic as the kind of people who are bringing influence back.

>> Ian Johnson: Well, I don't know if your point was sort of only the people who were doing critical work were born before the PRC. I'm not sure that was your part. Well, yeah, but they were. I mean, nowadays, AI Xiaomin was born after the PRC was founded, and so she grew up in the PRC.

And so, I think there's a number of younger people who are also involved in this. It's the same thing probably in our own lives or in our own countries, that often what gets people interested in something or they wanna do something is a personal experience. So it's often the people who experienced in some way the great famine, like Yang Jishung.

His stepfather died in the famine, and he wrote this book as a memorial to his stepfather, and so that's what he did. And another generation might have been people who experienced the Cultural Revolution firsthand. But now you have people who experienced the COVID lockdowns and the lack of political institutionalization in China.

I think a lot of people were sort of shocked, in a way, by Xi taking the third term. It kind of created this sense of hopelessness. Everybody has their own thing that drives them or motivates them. And I think that in any country, there are crises that pop up from time to time.

And China is no different in that sense.

>> Orville Schell: I think it does have a strong indigenous root. I mean, I remember democracy wall. That wasn't people who came in, who lived through the 40s. That was younger people just started popping up and putting up placards and giving speeches.

So I do think there's an indigenous power within China itself to generate the kinds of things that Ian's been writing about.

>> Glenn Tiffert: One of the things that the party can't control is people taking the party's own language and appeal to values and idealism and turning them around. I mean, this is exactly why Liu Xin is no longer taught the way he once was, because it's people look at the society around them, and they see a lot that looks familiar, right?

So they can turn that around and use it against the party. One group we haven't talked about, Ian, and I wonder if they came up at all in your research book is. There's a very large group now of wealthy private collectors who are going around and assembling impressive collections of primary source materials from the grassroots.

From town and county level archives or government offices, and oral histories that are being kept in private collections that are just sort of being whispered or talked about. You have to know a guy in order to get access to them. But in many ways, this is the future of archival historical research in China.

Because the party controlled the official state archives, are being restricted significantly and collections are being withdrawn. But in the meantime, has always been the case in China back into imperial times, wealthy private collectors would maintain manuscripts and copies of things that had been censored by the state. And this is where you go to find the richness of history in China.

>> Ian Johnson: Yeah, I know. I just was on picture. I mean, this used to be, second, I'll go back here. This is kinda funny. Yeah, so this used to be a great way to find documents in China. You'd go to the old used bookstores, used book markets. There's one place in Beijing, Panjayuan, where you could go.

And it was sort of this time partly when all these old founding. So members of the PRC were dying and their families were just getting rid of all of their personal papers and often selling it to scrap paper sellers. And after a while, scrap paper sellers would take it to Tanjiayuan and get more money for it than they would get if they just pulped it.