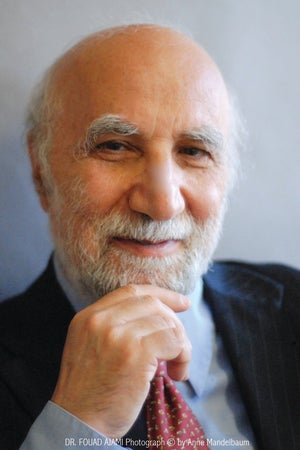

Fouad Ajami, an American Journey and his Pride in America

My brother, Fouad, died of cancer, and he will always be remembered for his love and pride in America. In lengthy and often weekly phone conversations, Fouad spoke of America as a beacon for a better world for all to see and emulate.

Fouad spoke softly but with pride about his cultural inheritance of his youth. To paraphrase, Fouad’s colleague, the leading Princeton Scholar, Bernard Lewis, Fouad melds his world views from a life in a Shia’ family in southern Lebanon with what he learned on his journey in becoming an American. Lewis writes, “He combines the understanding and concerns that are the birth right of the one with acumen and integrity that are the inspiration of the others.”

Fouad was a brilliant thinker and a great scholar with a clear-eyed vision of the Arab-Muslim society and its malaise with its lack of democracy and the demonization of the West and others they labeled as Zionists and Imperialists. He understood the Arab mindset that portrayed the West as a land of infidels, to use their term, to be kept at bay and to be invited as centurion to defend them from their own internal follies and disorders. At other times, they taunted and terrorized us with acts of horror, such as on September 11th, 2001, along with a cycle of escalating violence. Fouad showed us how this Arab mindset gave rise to terrorists and to the “true Muslim believers” whose sects discarded reasoned norms to use terror on all who stood for liberty. They unleashed terror on us and on their own citizens and neighbors. They thought they could redeem themselves and in their own way return to a glorious Arab-Muslim inheritance. Fouad understood the dream for glory, but soundly articulated how their sectarian terror obliterated sensibilities, communities, and their own culture, destroying their dream palace.

Learned colleagues, contemporaries and media commentators generously described Fouad as a brilliant social scientist for both the scholarship in his writings and his public comments in the media.

He was described as an insightful and gifted writer. His colleague, Michael Mandelbaum, from Johns Hopkins University, described Fouad as “a public intellectual” noting that “his published works will be consulted a hundred years from now by those who are wishing to understand the Arab world of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.”

To me, Fouad was first and foremost my brother who exhibited early in life a gift for language which blossomed into the poetry of political analysis. I, too, will miss this brilliant man who gave us honest perspectives on the troubles of the Arab-Muslim world. He was my younger brother, and I can speak of his compassion for people, his humanity, and his generosity of spirit continually exhibited during our childhood and in our journey together in America.

He expressed genuine concern for all people, especially the less powerful and those robbed of freedom. His life reflected his roots and what our mother and grandparents taught us. Their lessons stayed with him, anchored him, and shaped his views of the world.

Fouad was born and grew up in our paternal grandfather’s home with many members of our extended family in the village of Arnoun, a little hamlet in the foothills of a once majestic crusaders’ castle, “Beaufort Castle,” a structure that was built by the invading crusaders.

Standing in that castle, a favorite spot of his where we both played and often got into mischief, you can look as far as the eye can see to the Mediterranean and to the beautiful surrounding landscape of South Lebanon and Israel.

Our paternal grandfather, Mohammad Daher Ajami, was a learned man who briefly studied to be a cleric, a sheikh in the holy city of Najaf, Iraq. The “Sheikh” was a tall, handsome man, an excellent horse rider with a brilliant mind and commanding presence, and a great story teller. He tutored and nurtured Fouad, describing to him the world beyond our village and his abbreviated journey to Uruguay. My grandfather later became a Mukhtar – mayor of his village. There he championed education which included that of his own daughters who were enrolled in catholic schools in Nabatieh, an uncommon deed for a Muslim cleric.

The Sheikh’s best stories, however, were of our neighbors and friends whom he often visited in what is now Israel, to meet with friends and return home with loads of his favorite fruit, Java Oranges, proudly brought back to share with the many share croppers who tilled his land.

Our maternal grandfather, Mohammad Zein Al-Abdallah, of the city of Khiam, a stone’s throw away from the Israeli town of Metula, also indulged Fouad’s curiosity. He told stories about the Abdallah clan of Khiam, one of the largest Shia landowners in that community and their dealings with their Jewish neighbors during the time when the borders were open and free. During that time, many South Lebanese found it easier to conduct commerce with their Jewish neighbors to the south rather than journey to Beirut or Sidon, due to the lack of roads and supporting infrastructure. Mohammad Zein also spoke warmly of his Christian and Jewish neighbors and believed that neighbors who built structures together and worked together side by side would always want to live in peace and harmony.

Both grandparents instilled in Fouad a sense of a shared humanity of all religions, where tolerance and unconditional acceptance of others could be the building blocks for those who dreamt about a better future.

Similar to other prominent South Lebanese Shia, our family moved from the small village of Arnoun to the city of Beirut. Fouad always returned to Arnoun during the summer but lived with our family during the school year in Beirut, a city by the Mediterranean known as the Paris of the Mediterranean.

In Beirut, Fouad spent his time becoming citified and loved riding the street cable cars. He also was an eager, ambitious student, who loved to read. During his high school years, he enrolled in the Protestant College and the IC – International College, a preparatory school for students who aspire to study at the American University of Beirut.

Many of his teachers were American expatriates who spoke of life in America. At the IC, Fouad looked up to a gifted American teacher known to me as Mr. Miller. Fouad would often relate to me Mr. Miller’s stories about a vast country that allowed you to dream of great possibilities and travel in freedom during the summer in a second-hand car, bought for the meager sum of fifty dollars.

Fouad also spent hours in the reading room at the American Library in the West Beirut district of Al-Hamra. The library was full of books and glossy magazines about life in America. We poured over the latest pictures of slick American cars: Corvettes and Thunderbirds. A large American community lived in the area, and my aunt and her husband bought a building adjacent to the famous Commodore Hotel, an American hangout, where we often enjoyed sipping a Coke.

Fouad and I always talked about studying abroad. It was customary for Shia families with financial means to send their sons to study in British, American, French, and German universities to become medical doctors, engineers, and technocrats, among other professions. Fouad convinced me to study in America instead of Europe. He was adamant that only in America could a truck driver by the name Elvis Presley become a famous singer talked about so much in the glossy magazines we devoured. Many times he would say “if you could not make it as a doctor or engineer in America, you can always drive a truck, but leave the singing to others.”

I came to America, and Fouad followed me two years later. Here, Fouad found his place and was determined to make the United States his home and pursue his dreams. He attended college and completed his undergraduate and PhD programs in the Pacific Northwest, in Oregon and Washington, respectively. Later, his love for city life took him to Manhattan, Washington D.C and finally, to Palo Alto for a very successful career in American academic circles at the Hoover Institute of Stanford University as Herbert and Jane Dwight Senior Fellow, Johns Hopkins University as a distinguished professor and director of Middle-Eastern Studies, Princeton as a faculty member, and a well-respected member of the press and the media. But he was also husband to a loving, wonderful and dedicated wife, a father to an accomplished son from his first marriage, and a grandfather to two lovely grandchildren whom he adored.

I have learned, through the many expressions of sympathy extended to me, of Fouad’s generous spirit and direct personal contributions, financial and otherwise, to many individuals who have travelled to the United States for an education, becoming doctors, lawyers, and dentists, in other words, contributing members of American society. Through Fouad’s voice and his pride in his American identity, he was a model for other newcomers who now believe in the greatness of this country. In him, they found a way to love and respect America – its great opportunities and possibilities -- in addition to keeping the good of their own cultural heritage.

In my role as older brother, and often as mentor, I always protected him from neighborhood bullies who later assigned themselves the role of critic, distorting his fidelity to America and to his own ancestry. Now, as an adult and an American, I wanted to write this personal note to protect his legacy, integrity and honor his memory.

Hyphenated identity had no place in our thinking. We adopted America as our home and became proud Americans. Fouad integrity and pride in America conflicted with the muddled minds of some Arab-Muslim critics, who often speak in code and blame others for their own societal dysfunctions. They scapegoat America and the West, bringing their limited vision of nation building to this great country, the United States, and keeping fidelity to an antagonistic value-system that demonizes America.

Fouad swore allegiance to America and its value system to become a proud American. He wanted all men, women, children, Muslims, Christians, and Jews alike to experience the renaissance that is borne from nurturing the best in the human spirit, laying aside differences and working together to build, rather than destroy.

God rest your soul, Fouad.

Your loving brother,

Riad