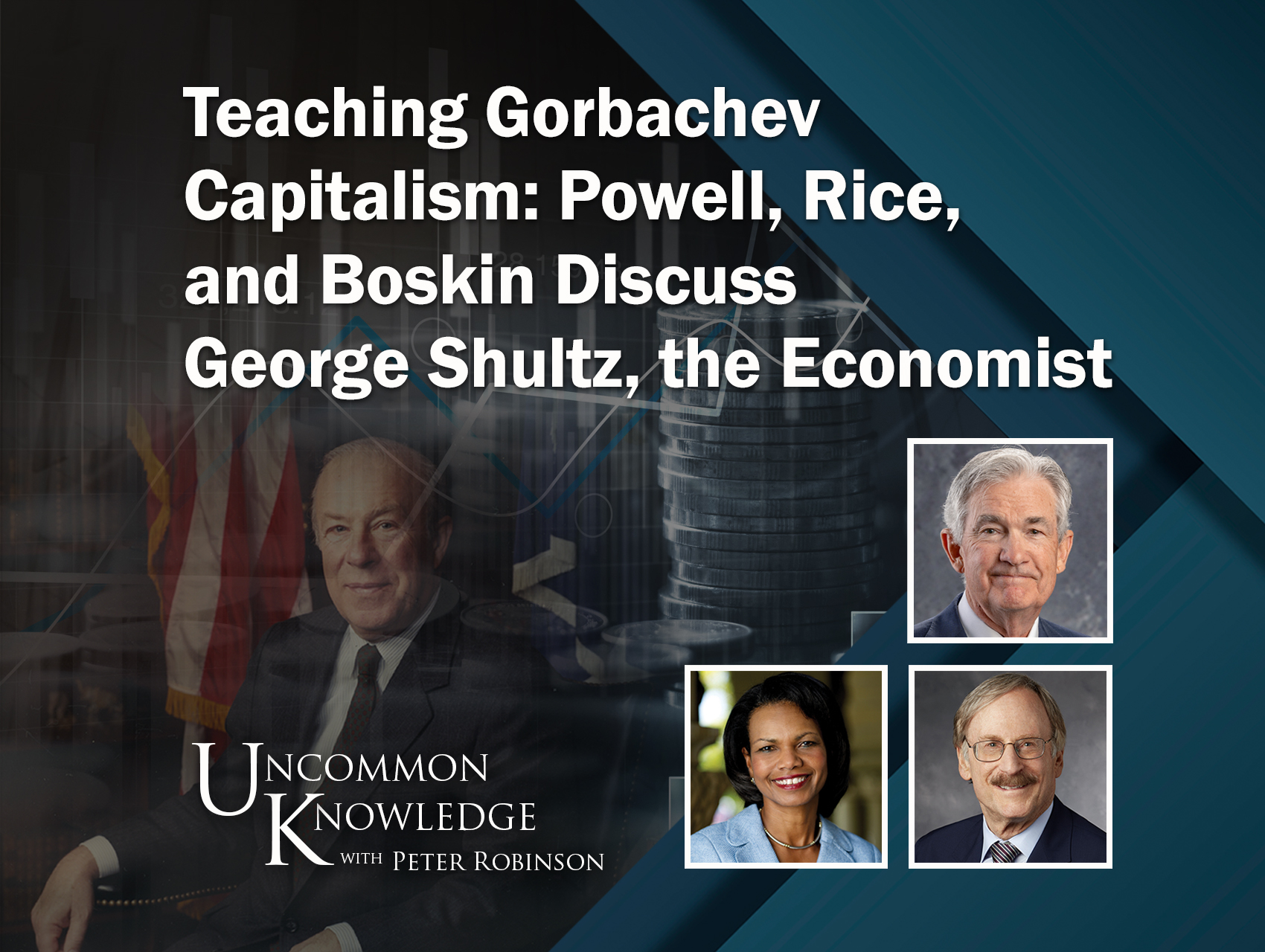

Hoover Institution (Stanford, CA)—Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell joined Hoover Institution Director Condoleezza Rice, Senior Fellow Michael J. Boskin, and Distinguished Policy Fellow Peter M. Robinson to discuss the economic legacy of former Secretary of State and Senior Fellow George P. Shultz.

Before leading the State Department for President Ronald Reagan, Shultz served as secretary of labor, secretary of the Treasury, and director of the Office of Management and Budget in the Nixon administration. Informing that service were years of work as an economist at the University of Chicago and MIT.

Speaking of Shultz’s legacy, Powell said he was someone who “combined strong principles and unshakable integrity with common sense and a practical, problem-solving approach to policy.”

“As one of the most successful policymakers of his era, George brought the intellectual rigor of an academic to the practical, constrained, messy work of policymaking through four cabinet appointments,” Powell said. “He dealt with many of the great issues of his day with remarkable success, and he kept at it long after leaving public office, making important contributions here at Hoover on healthcare reform, climate change, nuclear disarmament, and other areas.”

The lecture series, which previously featured a discussion on Shultz’s achievements for human rights, was made possible by the Koret Foundation.

Throughout the hour-long discussion, which was broadcast live on C-SPAN, Powell, Rice, and Boskin reflected on Shultz’s many achievements, including those lesser known, and personal qualities he exhibited even when he stood far from the limelight.

George Shultz on Racial Justice

Powell cited a 1969 episode he studied where Shultz, serving as secretary of labor, worked to push for full racial integration of schools in the US South, where White-led states and school districts were refusing to comply with the terms of Brown v. Board of Education, despite its being decided almost fifteen years prior.

“Essentially nothing happens in integration of the schools despite the striking down of ‘separate but equal,’” said Rice, herself a Black student in a still-segregated Birmingham, Alabama, during this period. “They just ignored it and ignored it and ignored it.”

Shultz brought White and Black representatives together on a commission from seven states where integration of schools had stalled. His thinking was that once they all started speaking together about the issue, the holdouts would realize that school integration would eventually occur, with or without them.

“This is sort of the full ‘Shultz’ playbook of bringing people together, treating them with respect, empowering them, enabling them to take on this terrible, difficult issue. And it really worked,” Powell said. “The schools did open without violence in these seven southern states, and it’s quite a remarkable story, and he really made it happen.”

George Shultz the Pragmatist

Working as an economist at the University of Chicago in the 1960s, Shultz despised the idea of price and wage controls. It was a view shared by many at University of Chicago, as well as the Hoover Institution. But in the wake of inflation that at one point hit 6 percent in early 1970, the Nixon administration instituted those controls, even as Shultz and others protested. But Shultz responded to this development differently than others. He stayed quiet and waited. And he didn’t relish saying “I told you so” when the measures ultimately failed.

“So, he lost the argument, but he understood who was elected and he was able to bide his time. And then when he had the opportunity, he worked to move things in the other direction,” Rice said.

“George was in that way, quintessentially a pragmatist always,” she continued. “He played a long game. And I think it isn't as well understood that when you’re in government, sometimes you’re going to win some and you’re going to lose some. But if you never lose sight of what you think is right, you might have a chance to correct it.”

George Shultz, the Patriot

Ever the consummate diplomat, Rice spoke of how Shultz would prepare ambassadors before they assumed postings around the world.

“There’s a story that when George would swear in, as secretary of state, our ambassadors, he would go to a big globe and he would say to the would-be ambassador, ‘Show me your country.’ And that person would point to Brazil or to Paraguay or to Kenya, and George would say [pointing to the United States], ‘No, no, this is your country.’”

Rice continued by saying it was stories like these that demonstrated how Shultz really viewed his home. “He just had an unfailing belief in this country.”

To close, the speakers offered Shultz-inspired advice to the Stanford students in the crowd, who were too young to have lived through the challenges Shultz took on, whether segregation, wage and price controls, or the Cold War with the Soviet Union.

“You can serve with integrity whenever, with anything you do—whether that's in public life, in the business world, in a think tank, in academia, you can serve with integrity,” Boskin said. “Try to do the best you can and try to make sure that you take your God-given skills and make the most of them. You only have one shot at it.”

Powell said he hoped Shultz would serve as an inspiration to young people to enter public service. “I would hope people would look at him as an example and think, ‘I’d like to do public service. I'd like to serve this great country and make my own contribution.’”