Join the Hoover Book Club for engaging discussions with leading authors on the hottest policy issues of the day. Hoover scholars explore the latest books that delve into some of the most vexing policy issues facing the United States and the world. Find out what makes these authors tick and how they think we should approach our most difficult challenges.

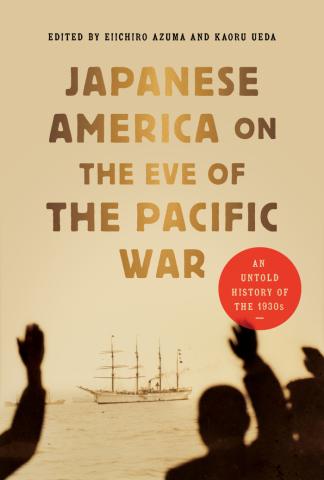

In our latest installment, watch a discussion between Michael R. Auslin and Tosh Minohara on Japanese America on the Eve of the Pacific War: An Untold History of the 1930s.

Friday, March 29, 2024 | 10:00 am PT / 1:00pm ET

WATCH HERE

>> Michael Auslin: Hello, I'm Michael Austin, historian here at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University. Welcome to our latest installment of Hoover Book Club, where we bring Hoover fellows and friends together to discuss their latest writings. Today, we are joined by Tosh Minohara, a professor of international relations and security studies at the Graduate School of Law and Politics at Kobe University.

Where he holds a joint appointment with the Graduate School of International Cooperation Studies. We'll be discussing today the recently released Hoover Institution Press book, Japanese Americans on the Eve of the Pacific War, An Untold History of the 1930s, authored by Eiichiro Azuma and Kaoru Ueda. Tosh, over to you.

>> Tosh Minohara: Hello, everyone, it's a real pleasure to be able to present this book today at this Hoover Book club. Let me jump right in. I have some slides that will go along with my talk today, so let me just share that with you all. Again, the book is Japanese America on the Eve of the Pacific War, An Untold History of the 1930s, by Eiichiro Azuma and Kaoru Ueda.

I had the honor to be able to be one of the contributors to this volume. So let me first introduce the entire volume itself. Now, this book was written to honored Professor Yasuo Sakata, who is known as a trailblazer in Japanese immigrant studies. And he is currently an emeritus of Osaka Gakuin University, which is based in the city of Osaka, western Japan.

I'm actually in Kobe, which is the next major city west of Osaka. I know Professor Sakata in the capacity as my external academic advisor when I was writing my master's thesis between 1994 and 96, even though I was not a student at Osaka Gakuin University. Because my thesis examined the anti-Japanese movement in California and its ramifications on US Japan relations.

He was very kind to take me on as an informal student, and so I attended his class and was able to receive much knowledge and insight. One of the main pillars of this volume is that it includes a translation of Professor Sakata's 1995 seminal paper, which is entitled, Fifty Years after World War II and the Study of Japanese American History.

This paper, for a long time, had only been accessible in Japanese, and this volume, for the first time, has made it available to the English language reader. Which I think is perhaps the largest contribution of these volumes. This volume, of course, is a compiled volume, it has many contributors.

Most of those who have contributed a chapter have worked with Professor Sakata, and they clearly share his passion for archival-based empirical research. This happens to be also the approach taken by my mentor, Professor Iokibe, who knew Sakata, who actually really welcomed the fact that I was also getting the insight of Professor Sakata.

And Professor Iokibe is known as the preeminent expert on US Japan occupation policy. Japan, in other words, US current relations, and that's exactly what my contribution is to this volume. Now, Professor Iokibe's relation with the Hoover Institution would be, is that his first research was on Colonel Ishiwara Kanji of the Japanese Imperial Army.

And this was of course, one of the topics of the late Dr. Mark Peattie at the Hoover Institution. And I also had the good fortune to meet Dr. Peattie at the Hoover Institution, and we discussed Ishiwara Kanji and whatnot. What makes Professor Sakata unique as a scholar of Japanese immigrant studies, it's the fact that he had the courage to tackle the 1930s.

And the 1930s is a period that most Japanese immigrant scholars avoided, because it is the time when US Japan relations sour, eventually leads to war, which had a tremendous impact on Japanese Americans. And as such, to honor the courage of Professor Sakata, this volume also places its primary focus on the so-called dark Valley of the 1930s and its examination of Japanese Americans in both California and Hawaii.

And of course, there's a vast difference between Japanese immigrants in these two, California state, Hawaiian territory back then, because those of Japanese ancestry in California were interned. Where in Hawaii, I mean, internment took place, but it was on a very, very different scale, and it wasn't entire families being interned.

So there is a difference, and I think this difference really comes out in this volume.

>> Tosh Minohara: Now, from now on, I'd like to focus on my contribution, which is chapter 9, which definitely is an oddball in this volume because it does not directly deal with Japanese Americans, nor does it examine the 1930s.

Rather, it examines the moment that Japan decides to go to war against the United States, and then why is this relevant? Well, it's because Japan's decision's to go to war against the United States made Japanese Americans an enemy alien for something that's somewhere American citizens. But nevertheless, citizens of a country when their home country was an enemy state.

And this really, really challenged identity, challenged allegiances, and therefore, it does have a tremendous impact on the story of Japanese Americans. Another focus or another objective that this chapter had is to sort of figure out where the point of no return was in this long and winding road to the Pacific War.

Sakata was very special in that he knew there was an official Japanese American narrative which was pretty much along the lines that a model citizen. But Sakata realized that Japanese Americans were very diverse. There were those who were very devoted to the United States, but there are also those who questioned the United States, especially because they were forcibly relocated.

And Sakata did not shy away from questioning the legitimacy of this longstanding model minority a narrative. And one of the things that I like to bring forth to sort of prove that Sakata was correct is that there was a school known as Heishikan, founded by the Gaimusho. And this was established in 1940, I believe, and this was a school for Japanese Americans.

Japanese Americans were selected, it was very competitive, but through various Japanese American communities in the United States. And once they passed exams, they were able to receive a full scholarship to study at Heishikan in Tokyo. And many of these were unable to return to the United States once war commenced, and so they remained in Japan as Japanese Americans.

So you can see that there's whole range of stories, and it's not just one narrative. Now, my research, like Sakata, is empirical based, it's multi-archival. I use sources in United States, Japan, UK, Australia, and Canada. And again, this goes really along the line of the historical research approach that Professor Sakata took.

And my chapter also challenges the longstanding assumptions like Sakata and posits a new interpretation as to what happened by incorporating the dimension of intelligence. And I think this is what's really new. And by incorporating this new element, this chapter tries to provide a more logical reason as to why Japan ultimately decided to go to war.

And on surface, it's very logical, because Japan GDP is about one-tenth the United States. It was totally utterly dependent on the United States for many strategic resources, including not only oil, but also steel and heavy machinery and whatnot. So why this country that's much smaller challenging United States?

And I tried to give a reason why this happened. Another larger premise this chapter has is the belief that history has utility. Thus, the lesson that history provides needs to be learned so that we can avoid similar pitfalls in the future. And it's my belief that history is a beacon that casts a light, however faint, into the future.

And this is what Dr. Graham Allison calls applied history. And I think this chapter is definitely a case study of applied history. Now, I'm going to jump right in. So every time you do empirical-based research, you need the evidence. If you're a paleontologist, it would be the dinosaur bones, and these are the bones itself.

This is what launched my research, it was that I discovered. I stumbled across documents that showed that the Japanese were actually reading US State Department cables. And this was something that was not known until I was able to discover these documents. And this is, again, it says the Japanese on the right with the calligraphy, it says national.

It's the highest level of national security. And this is a the Japanese decrypt of a conversation that was sent from Secretary of State Cole to the American ambassador in Chongqing. And this discusses the Kurusu-Hull conversation. And when you see this, you're, wow, so the Japanese knew a lot more then that they actually let people know about.

And this is another decrypt. I chose this one. There are about, I would say 50 pages of these actual decrypts. I chose this one because it has a stamp of the foreign minister, the deputy minister, and head of the America section. As you can see, it was distributed in a very small circle.

Just like American magic intercepts. So we have to keep in mind that it was well known that the Americans were reading Japanese decrypts. What was not known was that the Japanese were also doing the same. So both sides were reading each other's highly sensitive diplomatic cables. So this discusses again from Secretary of State Hall to ambassador to grew in Tokyo.

And this discusses the FDR memorandum on the ongoing US-Japan negotiations. And the US-Japan negotiations was, of course, the final negotiations to overt war. This one's interesting. This is because it's in English. And both the navy and the army and the foreign ministry, which is known as Gaim Michaud, all pulled their resources to decrypt American cables.

The army translated these American decrypts into Japanese. So that was the previous cables that I showed you, the decrypts that I showed you. This one, but the navy and the Gaima Michaud did not translate into Japanese because they can understand English at that level. They had the proficiency, but they added a summary.

And this is interesting because it has a summary right here, which you do not see in the actual cable that was sent out. Now, I've actually corroborated the actual cable and just Japanese decrypts. There are certain areas which the Japanese are not able to decrypt, but they have an estimated guess in brackets.

And you can understand by that the Japanese almost 100%. The accuracy was almost 100%, because even if you do not know a few words in a sentence, you can pretty much figure out what word comes in. And this, again, is the decrypt of the Toyoda- Craigie conversations sent from Grew to Hull.

So, of course, the Japanese are participants to the conversation itself. But through the decrypts, they can figure out what the Americans are thinking, what they are assessing, and what their next step will be. Again, this is Toyoda was, of course, he was a navy admiral, but also a foreign minister during this time.

Now, my main protagonist in this chapter that I write is the person by the name of Togo Shigenori, and he was a foreign minister. And people make history, and history makes people that's something that my mentor, the late professor Yoke, used to say. And I do honor this view, and because I focus on foreign minister, a person who was in a very important position at a very critical time.

But when you look into Togo Shigenori, his biography, it's very interesting. And so today, I'd like to spend a little bit of time to just sort of explain to you who this person was. Well, his father was born in December 1882, died 1940. And this was Togo Shigenori's father.

His father's name was Togo Jukatsu, and he was skilled potter, which is a key thing to know because most skilled potters from this part of Japan, this is Kyushu, were originally brought to Japan from Korea. The Togo family, for centuries, for at least a good 400 years lived in the Kagoshima prefecture, which is the western most prefecture in the Japanese four islands.

So it's Kyushu is the western most major island, and Kagoshima will be on the very southern tip of this island. He was an ethnic Korean. So you have an ethnic Korean who was foreign minister on the eve of Pearl Harbor, which I think is quite fascinating. There were 360 Koreans in his village.

Now, you may think, this guy was in Japan for a very long time, so he's ethnic Korean. But perhaps it doesn't really matter that much. But the fact is, is that until the Meiji period, this family was not allowed to mingle with other Japanese, and so that the culture remained, the language remained.

And this was because during the Japanese feudal period and also during the Edo period, that the lords of the domain were afraid that their knowledge of making pottery, which was highly valued, would leak. So therefore, they were isolated intentionally in order to protect the skills that they had.

So Togo himself, his last name was Park for a long time, since until he was four. So he really does have this identity as being a Korean Japanese. He enters the faculty of letters at Hokkien Pearl University. Which shows you in Japan, and this is true for even the military, too, back then, is that regardless of your background, if you are able to pass the exams you were treated equally.

And there is a very equitable system, Mary based system. And Togo studies German literature. So he's a little bit different than his other Geimshop here. He doesn't go to the faculty of law, and he also majors in german literature. He graduates in 1980, 1908, passed to the foreign service exam, which is very competitive, and so it takes him three times to pass.

Many of his peers pass it on the first go. So it wasn't like he was a bright guy, but a little bit different than his other, more well known peers in the foreign service. Now, his batch mate is the famous Amau Eiji, who is known for his declaration 1934 of the so called Asian Monroe documenthood.

Togo is very interesting in that he's very international. He marries a German Jewish woman named Eddie de Lalande, who is a widow of a famous German architect. Now, the late husband has many buildings still remaining in Japan. One has to one happens to be in Kobe. It's known as the Weathercock house, a western style building in the so called foreign settlement in Kobe.

So it's kind of interesting to see how something that indirectly relates to my research also has it still physically remains in Kobe. He is appointed to ambassador to Germany in 1937, but is recalled from his position when he repeatedly clashed with foreign minister Ribbentrop over Nazi policy towards the Jews.

His wife is Jewish, and he feels that it's completely wrong because he's, of course, Korean Japanese. He's never been treated in a bad way, so he just really questions his policy. He's recalled and then next, he's appointed to the ambassador to the Soviet Union in 1938, but he is forced to resign when the hard learner, Matsuoka Yosuke, enters the Konoe cabinet as foreign minister.

So what's clear is that Togo is not a hardliner. He is not a hawk among the Japanese diplomats. And therefore, when things the situation between the United States becomes very tense. He is very reluctant to enter that cabinet. And this cabinet is Tojo was led by Tojo, who is a army general, because he thinks that this cabinet is too warlike.

Tojo had always been hardliner, but he is persuaded by the senior statesman, Makino Nobuaki, to join the cabinet, saying that you are the correct conscience of Japan. You are the only person who can play a pivotal role in preventing war. And you can do that by entering this cabinet, despite your disdain for General Tojo.

Tojo is prime minister, interior minister has several portfolios. Now it's interesting because Tojo, even though he was a hardliner, he was chosen to become prime minister. And of course, the Japanese emperor was behind this because they thought they can control him by making prime minister. Because he will have to serve loyally to the emperor.

And Tojo does change. This is called the so called Tojo volt Foss. From a hardliner, he becomes somebody who's willing to seek a diplomatic solution to resolve the situation with the United States. But then you have Togo, who, as you will later know, in my talk, he reverts the other way.

So you have a Tojo volt false and a Togo volt false. Now, Togo is a determined realist. And to show how far he was willing to go to avoid war is the fact that he leaks the details of the September 6 imperial conference. This is the most highest level conference that you have in the Japanese government in its done in the presence of the emperor.

And the September 6 imperial conference is quite special in that usually the emperor just sits and does not comment, but on this day, he comments. He recites a poem saying that he wants to avoid war with the United States, that he wants to have calm seats. Togo divulges the content of this imperial conference to Ambassador group, saying that even the emperor himself is against this war.

But there's still some hardliners left but please come. Please convey to your government that it's not a monolithic block not everybody wants war.

>> Tosh Minohara: Now, I've been to the Togo Shigenori archives just to show you some photographs. This is a young diplomat Togo on your left. In the center is German wife.

On the right hand side is, well, on the top is the archive itself. And below is the main gate so this is where Togo's resident used to be. You can see that as a wonderful gate. It shows you that, as he became very wealthy. And below you see some of his writing, his handwriting.

>> Tosh Minohara: Now, I earlier said that Togo entered the Tojo cabinet reluctantly, very grudgingly, and he sets forth three conditions that Prime Minister Tojo needed to accept. One was that a diplomatic solution must be of utmost priority for the new government, and he will resign if peace cannot be attained.

He also insists that the navy minister must not be a hawk. What happened is you have Admiral Shimada Shigetaro, who is on the far right on the top of here. So you have photo of Togo, and then you have a photo of Tojo, and then you have Admiral Shimada he is appointed.

Now, Shimada is basically a yes, mahan to Tojo, perhaps the most pro Tojo person you'll find in the navy, which generally disdain the army. But Shimada Shigetaro was definitely not a hawk. He was, back in the day, called a saloon door, meaning that a saloon door opens both outwards and inwards.

That he was pretty much would sway in the wind. So not really a person of principle, but he was not a hardliner. And Togo insists that he also must be given a free hand in reforming the Gaimusho. What he does is, he pretty much cleans house when he becomes foreign minister.

He purges the so called pro-Axis renovations, these are the pro-German, fascist leaning diplomats. He really was heavy handed in the way he relieves these people. And the Japanese bureaucratic system, it's very difficult to fire people, but he finds a way, and it really shows you that he's intent on seeking peace with the United States.

And his card to use to solve or to resolve situation in the United States is two peace plans. One is called Plan A in English, it's known as Koan in Japanese. And it pretty much since the main point of contention between United States and Japan back at the time is Japan's war with China, and Japan making inroads deeper into China.

So, he proposes that Japan will withdraw from China. And please keep in mind that China does not include Manchuria at this time, Manchuria was not considered to be part of China. And therefore we have the great wall that, that marks the boundary between China proper and the North of that.

Koan initially, Togo insists that Japanese army will withdraw from China in 5 years. The army says, no, no, no, it has to be 99 years. Toga raises his hand and disbelief, saying, I can't bring this to the Americans, I'm not gonna say 99 years. So he says, how about 15?

The army says, okay, how about 50 years? Again, not very workable, in the end, they reach 25 years. But Togo realizes the Americans are not gonna say yes to Japan withdrawing 25 years. So his next Plan is Plan B, which it's a lot more, it was considered to be a lot more feasible in that it's much smaller in scale.

And it's basically maintaining the status quo that Japan will not make any further inroads into China. And the United States will at this time in the United States embargo in Japan, that it will allow the export of oil to Japan. So it was just sort of lessening tensions and so that they can launch into another set of negotiation that can reach a permanent resolution to the crisis.

I'll talk about Otsuan later on cuz this is very key to my chapter. Now Otsuan is rejected by Tojo saying, no, I can't do this. There are, again, lots of other hardliners in the Imperial Japanese Army, but this is where Togo uses his ultimate card, he threatens to resign.

And Togo is like, you can't proceed without a foreign minister. So Togo's, he's okay, I need to, I'll reconsider my position. And of course, Togo people, those that are close to Togo, believe that this is not the moment to resign. So both Makino and Yoshida, who, Yoshida who later becomes prime minister in the post war period, say, no, no, Togo, this is not it, you can threaten to resign, but don't resign.

You gotta, that's your ultimate card, we'll have to use that at the moment in which peace is completely lost, because you can't go to war without your foreign minister. And so Plan B is submitted as the most viable compromise to be submitted to the American government. Now, what is this?

Well, I told you what the Plan B is. And, but at the same time, the United States had so called the Hull four principles, and the Hull is again secretary of State Cordell Hull. And an American foreign policy can at times be very principled. And the principles that were raised at this time towards Japan were the four things that I write here.

I respect the territorial integrity of China, non-interference and internal affairs of China, maintaining an open door in China. And maintaining the status of quo, which it actually goes back to John Hay and his open door notes. But these were the principles in the United States. Definitely, they were willing to negotiate because a war was already taking place in Europe, cuz lots of Germany invaded Poland in 1939, and so war was engulfing much of Europe.

So it did not make sense to open a second front. Of course, the British and Australians applied pressure to the Americans because they didn't want Japan to open up another front. The fear was that Japan would go ahead and take all the British possessions in Asia and would also advance South and try to invade Australia.

So they wanted to appease Japan because they could deal with Japan after they deal with Germany. And this led to the creation of so called the modus vivendi, which in the Japanese is in the characters there, zante kyotiya. Which basically means, just let's hold things for a little bit, which means that it was very close, the Japanese ultima, maintaining the status quo.

But it's important to note that both sides did not know that they were trying to create a short term resolution to make an asset scope. So the modus vivendi was created independently, thats Plan B is a key thing to know. This is where the so called Togo's volte face takes place.

And it was very unfortunate, I think, in Japanese history, because again, he was supposed to be the immovable dam in Japan's path to war, that he was gonna stand in the way and not allow Japan to go to war. But yet in the end, Togo supports the war.

And this has been a mystery in Japanese history for a long time, which I hope my chapter was able to explain why Togo took the action that he did. November 22, 1941, a very important meeting takes place between the Dutch, Australian, British ambassadors and the Chinese minister. They meet in close office, and this is the first time that Cordell Hull reveals the contents of the modus vivendi.

And this goes very much in line with America's Germany first policy, that is, that they will deal with Germany first. But the Chinese, the Dutch, Australian, British ambassadors are quite content. Okay, it's Germany first, and we're not gonna force Japan's hand. But the Chinese minister Hu Shi is infuriated because he thinks it's basically a selling out of China that you're going to, by focusing on Germany, you are ignoring China's situation.

Hull says, okay, I understand you're upset, but please send this decrypt back to your home government, to Chongqing and the Dutch ambassador. Dutch, Australian and British ambassadors also do the same because they need to get the approval of their home governments. Togo learns of the content of the modus vivendi through the Japanese decrypts.

I already showed you the Japanese were able to read American cables. I believe that he read the Chungking, the one that was sent to chunking, because the Chinese cables were the most easiest to read. Because they didn't use cipher, they just used, basically codes, they used numbers to represent Chinese characters.

And this was because they couldn't Romanize Chinese back then. Because it was pronounced differently in China's huge different pronunciations for the same Chinese character. And so the only way they could communicate was through writing in the Chinese character. So it took about 3 to 4 hours, which was much shorter than the other English language decrypts, which took a couple of days.

Togo is naturally lady, I mean, just put yourself in the shoes, I mean, he was thinking of this, and he submitted his plan B. He sees this Modus Vivendi, and he thinks, the Americans are countering his MOSFET, and it was very close. So he believes the crisis can be averted.

But what happens is, on November 26th, the American final response to Japan's plan B is submitted. And this is known in history as the whole note. Togo is stunned, and you can tell because he writes in memoirs that I was utterly blinded by disbelief. And again, the fact that he writes that hints that, he was expecting something altogether different.

And he's shocked because the whole note, there's no motives of ending the whole note. It's basically back to the same four principles. And so the United States had pretty much rejected Japan's plan B.

>> Tosh Minohara: This is where there's conjecture. I believe that Togo, seeing the decrypts of the Modus Vivendi, felt that this would be submitted to him as a counter his plan B, so in that the situation could be resolved.

But the moment the Americans dropped the Modus Vivendi, he realized he felt that America had decided to go to war. And Togo is a realist, he's not a dove, he's not a pacifist. And so he believes that if the United States has decided on war, that Japan had no choice but to go to war as well.

And this is where he writes in his memoirs, Japan now had no choice but to rise. And this is immediately impression, right after reading the so called hold note. The moment foreign minister Togo gives us one diplomacy is when I believe, Japan crosses the Rubicon, it's the so called poetic turn.

So it's not the Manchurian incident, it's not the second son of Japanese war, it's not the tripartite pact. I believe this was the ultimate moment in which Japan could no longer return. That the wheels started to Spanish on a course in which Japan would collide with the United States.

So what are the lessons that can be learned? And this, I think, is really important if you are practicing so called applied history. I like Mark Twain a lot, and one of the things that he wrote and I thought is definitely true is the, quote, there that you see in front of you.

What gets you in trouble is what you think you know, but it ain't so, and that's exactly what happened in Toga's case. It's very hard to interpret the actual intent of your opponent just through decrypts. And sometimes it can be very misleading because it's not intended to be read by a third party.

So I think this episode, very unfortunate episode, shows you the so called fog of diplomacy. That limited information and the misconstrued constraint of intent can cause problems, that deduction is at times imperfect. And in this case, the results were disastrous because he was the last impediment to Japan's path to war.

Once he gave up and decided Japan had to rise now, then there's nothing stopping Japan. Caution is warranted when interpreting information that is intended to be read by third parties. So, and this is true with the Toga Nomura cables, Nomura was Japan's ambassador to Washington. Togo is sending all these cables saying, Nomura is a former, not only is an admiral, he was a former foreign minister.

So Togo has to send out instructions to, so is much more senior than he is. But Nomura has a tendency, because he wants to World War II, to sort of putting his personal views into official correspondence with the United States. And Togo does not want Nomura to add anything to plan B, whether it be in writing or verbally.

And so he says, this is Japan's absolutely finalized proposal, even though this was just telling Nomura, don't mess with plan B. But the United, I've actually seen American decrypts to that, and that's underlined by somebody in the State Department. It's a double underlying, and this final-like, absolutely final-like proposal, it was obviously construed to be and ultimatum.

So I think this sort of explains why the Americans decided to drop the most Vivendi. Because they thought, well, most of India is very close to plan B, but it's not an exact match. But if the Japanese are saying, we're not gonna budge on plan B, this is it, then why show the Muslim.

It'll just show the world that the Americans are willing to sell out China at a critical juncture. So without nothing to gain, and if you're gonna gain peace by that, then of course, it's worth it. And so I think, again, it shows you the dangers of trying to read the intent through this decrypts.

>> Tosh Minohara: And I also think that it shows that wishful thinking is human nature, I think expectations clouded judgment. Togo really wanted peace, and I think that clouded his judgment, and another way to put it is we tend to see what we want to see. So he read into the decrypts what he wants to see, and this, of course, is known by psychologists as scenario fulfillment.

I'm not gonna get into the details, but when the American warship down, the Iranian Air Flight 655, is considered to be a classic example of scenario fulfillment. So, in other words, the crisis situation in November 1941. And Togo's eagerness to avoid war created a pitfall that led to a tremendous intelligence failure on part of Japan.

And it's much more gray for Japan because the United States also suffered heavily in the Pacific war. But Japan lost the war, and it ended a regime. So, I mean, the consequences were very, very grave.

>> Tosh Minohara: And this is my final slide. One of the things that I believe my chapter reveals is the intricacies of what was going on in the Japanese government by that during this time.

One of the questions that was all in my mind as I wrote this chapter is, who's the adversary? That you have competing institutions, even the United States you have competing institutions. But in Japan's case, you didn't have a strong central authority like president right now. The prime minister was not, as he couldn't, control the navy and whatnot.

So you had many competing institutions, and they all were pursuing their own interests. And they thought it was national interests, but other institutions thought otherwise. For example, I have two examples here. One is the so called Miyazaki operation that was launched by the Guy Michelle. Guy Michelle wanted to end the war in China.

They sent a well known Asianist to go to China, meet the Chinese to sort of find a solution to the Chinese, the second Chinese Japanese war. Well, what happens is that when moment Miyazaki lands on the continent, the Asian continent, he's captured by the Japanese imperial army because the Japanese imperial army were reading Gaima show cables.

And so here again, you have your own team sort of obstructing what you're trying to do. It shows you the complexity of what was going on in Japan in 1941. And also you have the Kwanoi Roosevelt summit, in which this was a last ditch effort by Prime Minister Kwan, had to meet FDR, a summit that was to take place in Juneau, Alaska.

But again, this falls through. It became known after the war that Kwonoi actually had a personal letter from the emperor himself asking, this is kinda strange. But asking for Americans to not go to war because he was against it, and that he will do his utmost to prevent this war, but that he needed Americans understanding of Americans and their help.

This fell through because Cordell Hull insisted, Roosevelt, you don't wanna go all the way to Alaska for a meeting that be fruitless. Says, why don't we have the Japanese tell us beforehand what they're willing to bring to the table and what they will agree to. Konoe can't do this because he can't say, I have a letter from the emperor because he knows the army will find out.

And so it was really unfortunate that the summit did not take place. Of course, the advance could have taken an altogether different path. And considering the counterfactual, I think this is really important because it shows you the magnitude of Togo's final decision to stand up and rise. What happened if Togo had not read the most event?

What did he had no access, he didn't have access to the decrypts. Well, I believe he would surely have resigned since he realized that he was the final card in preventing this war. Now, the imperial household would not have allowed the appointment of a hawkish replacement because, I mean, it would be a cabinet that was formed to go to war.

And that would make the imperial household, the emperor, complicit to this. And so they probably would have said, okay, ask Togo not quit. Convince them to come back, something of that nature, but not allow an appointment of a hawk foreign minister. The problem is that I've been talking today on diplomatic time, but there was also the military time.

The Japanese combined fleet has already left in the Kurils and is sailing to the northern Pacific. It's just a few hundred miles north of Hawaii. This is a different set of time. What is Admiral Yamamoto gonna do? Is he gonna anchor his ships until the Japanese government can figure out who the foreign minister will be?

No, I think that he will lose his window opportunity to attack. That he's not gonna risk his navy, is proud imperial fleet, is gonna have the ships come back. And then a week later, from Pearl harbor, what happens in the eastern front is that the Soviets push back the Germans 100 miles.

And what becomes clear is that Germany is not gonna win this war with the Russians very easily, which would allow Japan to reassess its situation and perhaps sit out this war much like Spain did. So it's the diplomatic time versus military time.

>> Tosh Minohara: This is something that most people don't know.

But the navy had another set of plans, and what was actually implemented was climb Mount Niitaka, which in Japanese is Niitaka yama nobore, but the other one was, okay? The US Japan negotiations are making headways. Let's call off the attack. And that was Tsukubayama bare. The weather is fine on Mount Tsukuba, so there was the possibility that Japan could have avoided this war.

Then they would have said, okay, the weather is fine on Mount Tsukuba, lend back the ships. But I believe the Rubicon was crossed when foreign Minister Togo misconstrued American intentions. In today's world, I think there are a lot of similarities. Japan, Germany and Italy combined their strengthen to establish a new world order, which meant challenging the then Anglo US pacts.

Today, the challengers are China, Russia and Iran, with a few other countries that are unhappy with the current existing order, too. It's been made very clear that they want to change the existing order. The rhetoric that's used by these leaders really resonate with rhetoric used by the axis powers in the late 1930s.

>> Tosh Minohara: Are we towards the end of the so called interwar period? Are we heading towards another major war? The purpose of this talk is not to discuss that, but to keep in mind that when a crisis situation takes place, that there are a lot of pitfalls. And one of the pitfalls can be intelligence, in that in our attempt to try to avoid a major war that we misconstrue the intentions of the other side.

And so I think lots of caution is warranted, and I think history can always serve as sort of a guide to where we're headed and the lessons that we need to be careful of. Thank you very much. And this is just to honor my mentor. He passed away early in the month, is a great, great man with a person I know with heart of gold.

So I'd like to dedicate, if I may, this talk to the late Professor Makoto Iokibe, who was a great mentor to me. Thank you very much.

>> Michael Auslin: Thank you, Tosh, for a very detailed and interesting presentation on, I think, a history that Americans obviously don't know very well.

And, as you said, doesn't really quite fit with the rest of the book, which is on the Japanese American experience. We don't have a lot of time for questions, so there's questions I could ask on the book, questions I can ask you. Let me start with the end, where you talk about the difference between military time and diplomatic time.

And it seems that there may be a third time in there as well, which is political time.

>> Tosh Minohara: Yeah.

>> Michael Auslin: Which is the level where the decisions were being made at the cabinet on the Imperial War Council.

>> Michael Auslin: Does that supersede both military and diplomatic time? Meaning your argument, it's a lot of inside baseball that Americans won't be familiar with.

>> Tosh Minohara: Yeah.

>> Michael Auslin: But if Hogo had resigned, then your argument is that the attack could not have gone forward because it would have ground the politics.

>> Tosh Minohara: Sure.

>> Michael Auslin: Which seems to be opposite or at least counter to, let's say the Tuckman thesis, that once you get the wheels turning and as you said, that the task force was already in the ocean, it's already in the Pacific, that things then take on a life of their own.

So how do you respond, maybe to someone saying, well, but if the fleet had been launched, they were gonna do it at some point, or the politics could not have held? I mean, the normal operating of politics might not have held in such a crisis situation, so the end result being we would have had war anyway.

How do those factors into how you think about this?

>> Tosh Minohara: Well, I think in Japan's case, it's really different than, for example, United States or Germany or the Soviet Union back then, because you just really do not have this strong political decision-making figure. I mean, the emperor could not be directly involved because he couldn't be responsible for anything.

Prime minister was General Tojo, he could control, he can rein in on the imperial army, but that was pretty much it, again, it's going back to the competing institutions. When you have competing institutions at this level, I think the political aspect is relegated to perhaps a lower tier.

And the focus becomes really the military time you can't disregard because the fleets are actually out there. And the diplomatic, because you have the diplomatic time because you have to resolve the situation with the United States. Well, the thing that I did not talk about, because it would open up another whole can of worms, is that the imperial Japanese army was a completely different animal.

The navy had a plan to actually call off the attack and return. Now, believe it or not, the Imperial Japanese army, because they had never supposedly lost a major war, did not traditionally have a plan to withdraw. So, as you know Japan's attack on the Pacific war was two pronged.

The navy would attack the United States, the army would go into Southeast Asia, and it was actually the Malay peninsula. Japan army invaded Malaysia would later take Singapore, there was no plan to cull this off, there was no Tskubaya Mahade. So, what would have happened is that the army would have proceeded to invade Southeast Asia despite the navy calling off its attack.

And this is where we go into the conjecture, well, then what would happen? How would the United States respond? Well, in my study of American foreign policy during this time is that the red line was the Philippines. The United States would not go to war over Japan's invasion of Malaysia, that was a British thing.

As proof, when the British asked the Americans to station trips to Singapore, the United States declined because it would be a tripwire. So, I think it would have been a really strange situation in which you have Japan fighting a war in Southeast Asia, but not the United States.

But again, this is all history that did not transpire, and we could argue about it all day, but to show you the differences that existed in Japanese institutions.

>> Michael Auslin: And something you talk about in the chapter, which you didn't get to talk about much here is the decoding.

I mean, you started off a little bit with that, can you just tell us a little bit more about that? Because obviously, in the histories of the war on the American side and the British, magic and purple, they all enigma, they play huge roles. Nobody thinks that the Japanese could actually do decryption.

>> Tosh Minohara: Absolutely, and that's a very good question, and it's because there are different biases that existed back then. And one is that, well, it goes back to Pearl harbor, how that Japan could never pull that off. I mean, Japanese are genetically in fear, in eyesight, they couldn't fly planes, and that really had an impact.

And this perhaps goes into the book about how the Japanese Americans suffered these various prejudices. But the basic assumption, both the British and American intelligence sources, that the Japanese were not bright enough to be able to decrypt. And even a report that was written in 1944, it writes that the Japanese, because they were so incapable, had to ask Germany for help.

And Germany initially helped the Japanese, but because the Japanese had nothing to offer in return, this cooperation was called off. Which was really not true because the Japanese had been reading decrypts much earlier, from what I can see, this all took place in the 1920s. And Japan admittedly was a late starter when it came to decrypts, because Japan was not a major participant in World War 1.

And World War 1 is the major battle in which people would communicate via air, right? It was the radios and whatnot which meant that anybody could receive it, so you had to protect it rather than the landlines. But Japan realized that after the war, quickly convened a meeting to set up its decrypting unit.

And surprisingly, it was Poland that offered help, it was a colonel, Koweleski, who was brilliant in math. He played a role in breaking Germany's enigma, even though the British get most of the credit for that. He actually worked out the formulations that allowed the Brits to do that, so why are the Poles helping Japan?

Well, it's because their mutual enemy is the Soviet Union, now, it's interesting, when Germany invades Poland and Japan has the Axis pact, then Japan becomes an indirect enemy to Poland. Yet the Polish continue the intelligence cooperation with the Japanese with the caveat that they would not share intelligence that related to the allied powers.

So anything that dealt with Germany and especially the Soviet Union, this cooperation would continue, so it really shows you the intricacies that took place during World War II.

>> Michael Auslin: So, this is not something that you obviously cover in the chapter, it's not something you talked about. I don't know if it's something you've looked at, but you've raised this whole issue of, as you said, you had the Mark Twain quote, things you think that turn out not to be.

So you're talking missed opportunities, misunderstandings, unmet and mismatched expectations.

>> Tosh Minohara: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

>> Michael Auslin: Can you flip to the end of the war? And if you can't, that's fine, we can ask something else, but can you flip to the end of the war? And is there in any way a similar dynamic at the end of the war to what you've identified in the beginning of the war in terms of all of this, you called it the fog of diplomacy?

The diplomacy and a fog of politics at the end of the war, that is just as interesting as what you've talked about at the beginning.

>> Tosh Minohara: No, yeah, no, absolutely, and this is where it gets very politically sensitive because how the emperor is revered here in Japan. And I don't wanna get in trouble here, but, and the end of the war is quite different in the Japanese decision-making process because the emperor plays a very decisive role.

He says, this is it, gonna end this war, and you have disgruntled generals, but, I mean, they're not gonna go up against the emperor. So to show such decisiveness, the question is, why couldn't you do that in 1941. And of course, the counterargument was, well, he didn't realize the war would turn out so badly.

And in 1945, Japan's been, it's been bombed every day. And so it was out of desperation that he attacked, and I understand that. But the fact remains that he was the key person in ending the war. But I think that japanese history would turn out to be much more happier if he had been that decisive in 1941, that it could have completely changed.

And then it goes back to Japan's security identity to this day, I am very frustrated. It's the reason why I launched my think tank, and we should probably share this too, is that the Japanese do really do not understand the importance of security. That the role that Japan needs to play in today's world.

And it's because it goes back to the war, that they lost the war, and they believe that everything that deals with military is bad. And it's this remorse that's continued into the new century, which I think really has to change. And one of the things that I think that you probably would, if you had time for another question this would be it, is that the parallels.

I think history rhymes at times, and the parallel, now the new challengers are Russia and China and Iran, and the rhetoric is very similar. Japan's inroad was into the continent, and that became a big point of contention between United States and Japan. Now China's expanding the other way into the maritime realm and it wants to change the status quo there.

And so is there a chance that there could be some kinda conflict as the United States does not want China to close the door in the Indo Pacific, just like dynasties didn't want Japan to close China from the rest of the world. So, I mean, there's parallels there, and I would be wonderingm delighted to hear your insight on that cuz I know you're an expert on that.

So what do you think? Cuz I think this really is a key part of this book, is that my chapter at least, to think about the implications of today. So, I mean, what do you think?

>> Michael Auslin: I appreciate it, I appreciate it. I'd love to answer, but I really would rather ask you one final question cuz-

>> Tosh Minohara: Okay, good, sure, sure. Okay., yeah, I shouldn't be the one asking questions, sorry about that.

>> Michael Auslin: No, no, no, I appreciate it, and I think we should find time to actually come back and talk.

>> Tosh Minohara: Okay, sure.

>> Michael Auslin: Not under the book event auspices, but under other auspices to talk about this.

But I actually did-

>> Tosh Minohara: I understand, yeah.

>> Michael Auslin: We only have a few minutes. And so I actually did wanna pick up on your comments here on the contemporary point about Japan not accepting or understanding security. And actually, someone who did try to work much on that was Professor Iokibe, who was your mentor and with whom I studied, of course.

>> Tosh Minohara: Yes you did, yes you did, yeah.

>> Michael Auslin: And so I thought maybe we could finish up, if you could take a few minutes, actually, just talk a little bit about who he was, his legacy. I think one of the great shames we have here in the States is that we really don't know great Japanese professors and scholars.

The work isn't translated as much, though some of his book on diplomatic history, I think was, I may have a japanese copy, but I certainly have a copy. Unfortunately, much of the work isn't translated, which is why this book, the Japanese America on the Eve of the Pacific War, is so important.

But maybe you can talk a little bit about Iokibe-sensei.

>> Tosh Minohara: Yes, yes.

>> Tosh Minohara: No, thank you for the opportunity to talk about him. Of course, he was my mentor. He was the reason why I became a scholar. I had other ambitions back when I was younger, and he's the one who guided me to this path.

But the thing that I appreciate most about Professor Iokibe, I mean, we disagreed on whole hosts of issues. But he was a person who really felt that US-Japan relations was important, that it was the core of Japanese foreign policy. And I see this because, in Japan, academics, you know, of his age, people in their 80s generally tend to be anti America.

The American Association for Japan for a long time, is to be really anti American for Japan. And it's cuz they viewed America as the hegemon, the preacher and whatnot, but to Professor Iokibe, that was irrelevant. He says, no, Japan needs the United States. And because he examined the occupation, you realize what the United States did for Japan.

That this was an undertaking that history has never seen before, that you have a country that is helping to rebuild and establish democracy in a defeated nation. And, of course, America had the reason to do so. And there were altruistic parts, but also non altruistic parts. It was about an American interest as well, but he understood that.

And I remember anybody who would doubt this, I remember this dinner that we had with somebody who was very anti United States. And Professor Iokibe, you know him, he was very mild mannered, actually became visibly upset. He says, I can't believe you do not understand why you US-Japan relationship is important.

And so for this, I mean, this is why I really respected him, cuz he really realized what was at the core of Japan and what was important for Japan. And for him, it was definitely United States. And this, I think, was very unusual for somebody born in the early 1940s to feel that way.

He didn't have any resentment, and he felt it wasn't that, of course he regretted Japan's path to war and especially what Japan did in Asia. But he actually was not just looking in the past, he was looking in the future. And he realized that, yeah, go ahead.

>> Michael Auslin: I was just gonna say, just at that point, the point about looking towards the future, he also wasn't just an academic.

Maybe you can talk about that.

>> Tosh Minohara: Yes, yes, actually he was the president of the National Defense Academy, which was Japan's West Point, Annapolis, Air Force Academy, all rolled into one. And then they also, because that was a graduate student in 1995. That's when suffered that massive earthquake.

Professor Iokibe realized that recovery from disaster was also really important. Because in 1995, the socialist government really thought it was Kobe's thing to deal with and that the government really didn't have much role to play. And he felt that was incredibly wrong. He felt that it was responsibility of the government.

And so when the 2011 Eastern Japan earthquake and tsunami hit, I mean, he was the chairperson for the committee of recovery. And he actually moved the Japanese government to play a more active role in recovering from the disaster. So, yes, it was more than academic. He understood security issues, and he also understood the importance of disaster recovery.

So, yes, he wore many different hats. And it's really, I think it's a big loss for Japan. I mean, I wish you would have been around for another decade, because of what's happening in the world today with Ukraine and the Middle East. That he could have been a really important voice to sort of point the correct direction for Japan.

And the fact that he's not around, and I guess it means that we need to sort of play that role now.

>> Michael Auslin: That's right, and I think that when you think about Japan today, I talk about this a lot here in Washington. It's a completely different Japan from 199q, 1995, 2001.

And it has been a progression, but Professor Iokibe played a not insignificant role in helping bring that new sense of Japan's role in the world, the one that you said still needs to be further developed, which is true.

>> Tosh Minohara: Absolutely.

>> Michael Auslin: He played a big role in that.

And so I think that's a nice way for us to-

>> Tosh Minohara: You would agree it's a work in progress, right, that Japan shouldn't be content. It shouldn't pat itself on the back, there's still more to do.

>> Michael Auslin: It's always a work in progress, until end days, it's a work in progress.

>> Michael Auslin: So I think we're pretty much out of time. It's a fascinating chapter in the book, again, it's a Hoover Institution press book, Japanese America. I was gonna say Japanese Americans, Japanese America on the Eve of the Pacific War. Again, most of the chapters are focused on the still relatively unstudied experience of Japanese Americans.

Your chapter is this fascinating diplomatic history with some intelligent skullduggery going on and a lot of what ifs. And so I commend it to anyone who is trying to figure out, how did we get to December 7, 1941. But the rest of the book also is just a fascinating look at something that should be better understood.

So, Tosh Minohara, professor at Kobe University, an old friend. Thank you for joining us today. And, again, I'm Michael Auslin for the Hoover Book club.

>> Tosh Minohara: Thank you for the opportunity.

ABOUT THE BOOK

The era sandwiched between the 1924 US Immigration Act and the 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor marks an important yet largely buried period of Japanese American history. This book offers the first English translation of Yasuo Sakata’s seminal essay arguing that the 1930s constitutes a chronological and conceptual “missing link” between two predominant research interests: the pre-1924 immigration exclusion and the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II.

The anthology pays tribute to Sakata’s role as a foremost historian of early Japanese America and transpacific migration while providing an opportunity for a younger generation of scholars to reflect on his contributions and carve out a new area of research in Japanese American history. Original and translated essays from scholars of varied backgrounds and generations explore topics from diplomacy, geopolitics, and trade to immigrant and ethnic nationalism, education, and citizenship. Together, they attempt to catalyze further research and writing based on the thorough and careful analysis of primary-source materials, an effort that Sakata spearheaded in both the United States and Japan.