In April, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank jointly hosted a weeklong series of meetings in Washington with experts from around the world focused on issues these organizations are prioritizing. In the middle of the week, after existentially necessary sessions on topics like “Is a Feminist Vision on Public Debt Possible?” and “Eighty Years after Bretton Woods: Towards Rights-Based Decolonial, Green, and Gender Just Transformation of the IFA,” these globally recognized experts turned their attention toward a subject that has captivated big-government policy makers for more than a decade: global taxation.

This session specifically discussed adopting a “progressive global [tax] agenda in [taxing] the super-rich.” Notable attendee and UC-Berkeley economist Gabriel Zucman described the scene on X (formerly Twitter),

There was palpable “tax the rich” energy in the room. . . . There was an absolutely *packed* room (+ overflow room) for our panel on taxing the super-rich. This is (at long last) emerging as a central topic of international economic discussions.

He then thanked the “incredible leadership” of Brazil—a country known for its staunch commitment to equal economic outcomes—in pushing for the institution of a global minimum tax. Unfortunately for Zucman and his colleagues, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen took some of the wind out of their sails last week, announcing that the United States would not support any global tax on billionaires.

Still, it is worth considering whether any of this would actually be necessary or whether this supposed cure to global inequality could potentially make things much worse.

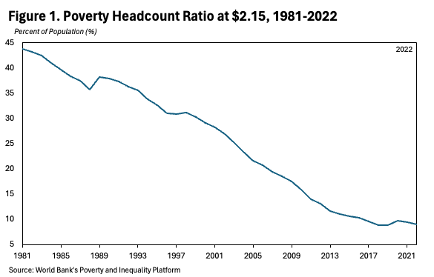

Somehow, without a complicated overarching, global tax regime, the world has seemingly done just fine in ameliorating poverty. Over the past forty years, the percentage of people across the world living in extreme poverty (defined by the World Bank as $2.15 per day in real 2017 dollars) has radically declined from almost 44 percent in 1981 to just 9 percent in 2022 (see Figure 1).

To the extent there has ever been a significant change in trend, the only time there was a substantial uptick to extreme poverty during this period was during the COVID-19 crisis, when countries placed extreme lockdown measures on their populations, causing abrupt halts to commerce and foreign aid. In 2020, Oxfam International warned that a hunger crisis brought on by extensive interventions could be worse than the crisis itself. One year later, the British NGO’s concerns proved prescient, as it would report that an additional twenty million people had been pushed into extreme levels of hunger, the number of people living in “famine-like” conditions had increased sixfold, and the people dying from acute hunger had begun outpacing deaths from COVID-19.

There is an underlying lesson from this experiment: no matter how clever policy makers may think their sweeping, society-wide policy agenda might be, chances are that massively important variables are not being properly factored into their model.

Policy makers would do well to follow the “Chesterton’s fence” principle laid out in English writer G. K. Chesterton’s 1929 book The Thing. That is, before completely upending an established course that has produced a stable society and reliable material returns, one ought to definitively demonstrate with clear evidence that this change would produce better results. While the scope of this hypothetical global tax regime would be completely unprecedented, we do have country-level evidence that is useful to consider in applying this principle of evidence-based policy.

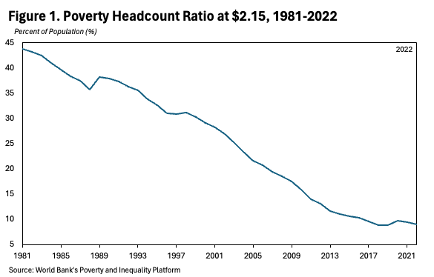

In the United States, Americans repeatedly hear that inequality has spun out of control, requiring a much more heavy-handed domestic tax regime to rectify these differences and even to save democracy. Policy makers, pundits, and academics often cite the work of Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman (collectively dubbed PSZ). These academics have famously argued that the pre-tax and transfer top 1 percent income share has increased dramatically from about 10 percent in 1960 to over 20 percent by 2020. However, due to data limitations, the authors have had to make numerous assumptions to which their conclusions about changes in income shares are very sensitive.

With this in mind, two other tax economists—Gerald Auten of the US Treasury Department and David Splinter of the Joint Committee on Taxation—found more muted changes. In their analysis, the authors find that the pre-tax top 1 percent income share increased from 10 percent in 1960 to just under 15 percent by 2020. The main difference involves technical estimation assumptions in measuring underreported income across the income distribution. For example, in a recent response to PSZ on this issue, Auten and Splinter show that the other authors’ approach to underreported income of non-incorporated (“pass through”) businesses increases the top 1 percent share of income by 1.5 percentage points. This is due to PSZ choosing to allocate about 50 percent of the underreported pass-through income to the existing top 1 percent. The problem with this approach is that work published in the National Tax Journal by Andrew Johns of the IRS and Joel Slemrod of the University of Michigan finds only 5 percent of underreporting went to the top 1 percent. In general, it’s the businesses reporting negative incomes doing the most underreporting. When including redistribution policies, the authors find virtually no change in the top 1 percent income share (Figure 2).

This work has been peer-reviewed and published in the Journal of Political Economy, an equally prestigious venue to those where PSZ’s work has appeared. Yet the press has paid much less attention to the government economists than to the UC-Berkeley revolutionaries.

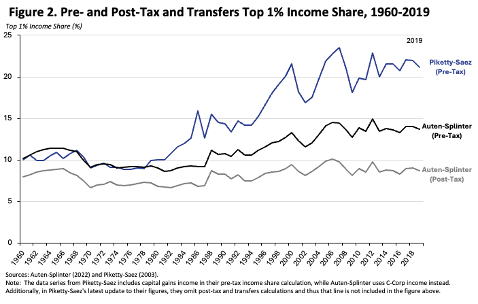

What about progressivity? While the income shares among the top 1 percent may not have changed all that much in the past sixty years, it could still be the case that the United States’ tax regime is not particularly progressive. However, this turns out not to be true. When looking at federal taxes, for example, in 2021 the top 1 percent paid 45.8 percent of all taxes, while the entire bottom 50 percent paid just 2.3 percent (Figure 3).

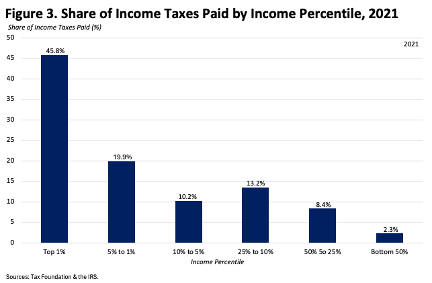

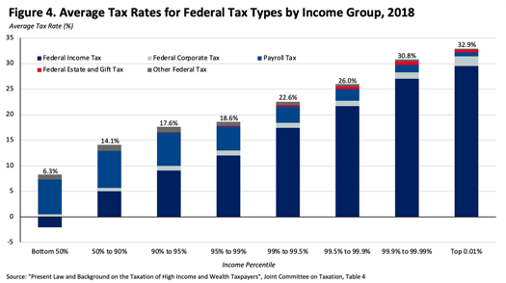

Another often-heard claim is that the rich pay less in tax as a percentage of income. Put another way, these taxpayers could contribute a greater share of total revenues, while theoretically facing a lower average tax rate. Yet, again, this proves to be untrue. When looking at a 2018 breakdown of average tax rate increases across income groups, the Joint Committee on Taxation surmised that the bottom 50 percent of taxpayers had a much lower average tax rate of 6.3 percent relative to that of the top 0.01 percent of taxpayers, who have an average tax rate of 32.9 percent (See Figure 4).

Coincidentally, Zucman has recently claimed in the New York Times that billionaires are now taxed at a lower rate than average Americans. So, what gives? How can one reconcile the previous paragraphs with that claim by Zucman? Phil Magness of the American Institute for Economic Research does a brilliant job in breaking down just how he manages to get there in a recent Twitter thread.

First, as Magness notes, Zucman apparently did not always himself believe that this massive convergence in tax rates occurred between the very highest and average income earners. In 2018, Zucman reported that the tax burden of the top 0.001 percent of earners barely changed between 1962 and 2014, decreasing just 4 percentage points from 44 to 40 percent. Yet, in 2019 (when he was coincidentally advising Elizabeth Warren’s presidential campaign), his numbers changed drastically, with his new series showing a massive drop from 54 percent in 1962 to 23.5 percent in 2014. The reason for this massive change was Zucman’s treatment of who bears the burden of corporate taxes. In his 2018 analysis, he followed sixty years of established economic research on corporate incidence, and in his 2019 version he decided to completely jettison this approach, changing it in a way that massively understated the tax burden of top earners. He then proceeded to ignore important benefits like the earned-income tax credit from his calculations, which significantly overstated lower-income Americans’ tax burden, and voilà, he managed to arrive at his preferred academic destination.

Proponents of progressive taxation could still argue that this level of progressivity remains insufficient and that there are still many societal problems that require additional funding. There are several problems with approaching policy with this logic.

First, the call for more progressivity assumes that increasing tax rates will increase tax revenues no matter how high tax rates go. Studying California’s Proposition 30 measure, which increased the top state tax rate on the richest Californians to 13.3 percent in 2012, Rauh and Shyu (2023) cast doubt on this conclusion. They found that the reactions from high earners to the new tax increase—expressed through either moving out of the state or reporting less income—eroded 55.6 percent of the windfall tax revenues over the first three tax years and over 80 percent by the final year. A persistent high-income earner (i.e., an individual in the top bracket for all years studied) would have reported about 11 percent more taxable income if that taxpayer had faced the pre-legislation marginal tax rate. And now that only the first $10,000 of state and local taxes is deductible against the federal tax, in effect since 2018, high-income Californians actually face an even higher marginal tax rate than at the time of the study. The top of the Laffer Curve has likely been reached.

Second, even if there are some tax increases on the high-income people that in some circumstances can increase revenues, the focus on maximizing tax revenues is misguided. Every tax involves some distortion of economic activity, and even just the current tax system has discouraged large amounts of economic activity, a point emphasized by the late Harvard professor and Reagan economic advisor Martin Feldstein. By the time the government is at a point where taxpayers are literally tapped out, the increases have already wrought much economic destruction. However, if the government’s primary objective was grounded in maximizing prosperity, policy makers and politicians would start by figuring out what economic and political systems would achieve the best long-term productive output of a society, subject to allowances for some redistribution, not simply what income tax rates maximize government revenues.

What is often implied in many of the suggestions from proponents of greater taxation is that countries that are currently economically strong will always be so, and thus the tax base can always be tapped for greater funds for new government projects and initiatives. But this ignores history and the reality that income and wealth are not guaranteed to grow in the areas that currently enjoy the highest relative levels of income and wealth. On the local level, consider a paper by Hoover’s own Lee Ohanian and co-authors Simeon Alder and David Lagakos published last year in the Journal of Political Economy. The authors find that much of the Rust Belt’s poor performance in the postwar era had to do with constant labor stoppages, pushing employers to leave the Rust Belt for other areas of the country.

On the country level, consider the United Kingdom. The most recent report from the Tax Foundation on “international tax competitiveness” ranks the United Kingdom twenty-ninth out of thirty-eight countries studied. Just recently, the country experienced negative per capita GDP growth and has seen its standard of living fall behind many peer countries due to its weak economic performance over the past decade. Last year, researchers from the London School of Economics found that while the UK, the United States, France, and Germany all experienced relatively worse growth rates in the aftermath of the global financial crisis relative to their previous trends, the United States produced 28 percent more value added per hour than the UK, and the French and Germans were 13 percent and 14 percent more productive per hour than their UK counterparts, respectively. According to the authors, half of this outsized slowdown was simply due to a lack of investment in capital and skills.

In sum, it is important to remember the wise words of former prime minister Winston Churchill when considering the usefulness of increasing taxation, “I contend that for a nation to try to tax itself into prosperity is like a man standing in a bucket trying to lift himself up by the handle.” Despite what you may hear, the narratives around income taxation and inequality pushed in the media are almost all completely wrong. Thanks to capitalism and free markets, far fewer people today live in poverty than they did fifty years ago, and inequality has not actually exploded. In the United States, the wealthy today pay the lion’s share of all taxes and substantial redistribution is already under way. While some redistribution arguably can on net be a good thing, too much redistribution will backfire and hurt the very people the government is attempting to help.