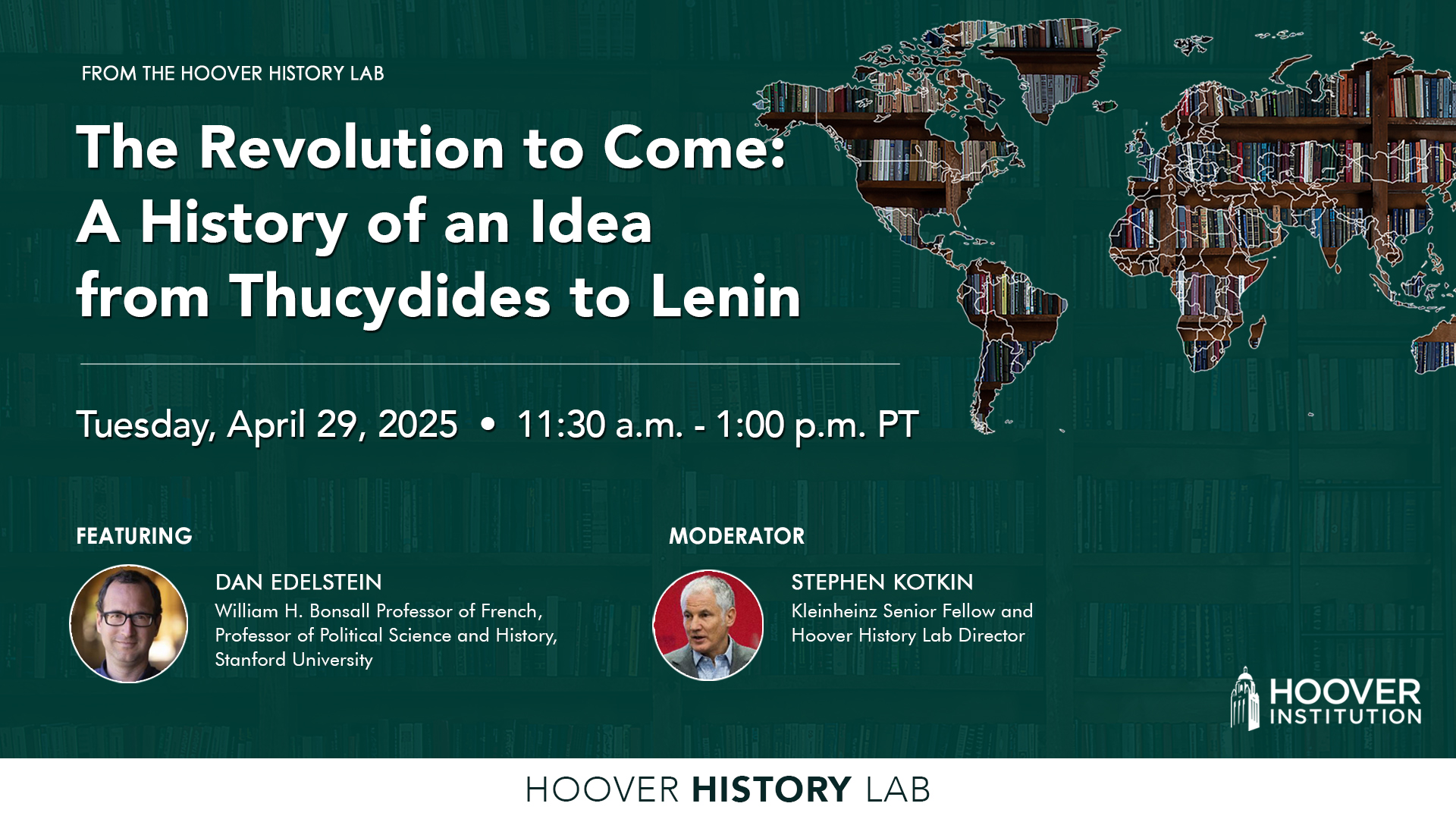

The Hoover History Lab hosted a Book Talk with Dan Edelstein - A Revolution to Come: A History of an Idea from Thucydides to Lenin on Tuesday, April 29, 2025 from 11:30 am - 1:00 pm PT.

Revolution! How did an event once considered the greatest of all political dangers come to be seen as a solution to all social problems? Political thinkers from Plato to America’s John Adams viewed revolutions as a grave threat to society and advocated for a constitution that prevented them by balancing competing interests and forms of government. The Revolution to Come traces how since the 18th century a modern doctrine of historical progress drove a belief in revolution’s ability to create just and reasonable societies.

WATCH THE EVENT

>> Stephen Kotkin: I'm Stephen Kotkin, director of the Hoover History Lab, and it's a thrill to welcome you all to today's book talk, the Revolution to Come. Some of you may feel like it's already underway and has been for some time now. We have Dan Edelstein with us today. Dan is a professor, French department, political science, history and every single other department at Stanford, by courtesy.

He runs the important college program, the first-year program for freshmen at Stanford. He's the driving force behind that program. He's part of the Stanford civics initiatives. We have the leadership here, the Stanford Civic Initiative as well. And he is a newly crowned member coming soon to the Hoover family as a Hoover Senior Fellow, by courtesy.

And so we're thrilled to welcome him to the family and also to hear him present what is now his fourth book on European intellectual and political history. Revolution has to be among the most important concepts and phenomena of the modern era. It's hard to think of too many that are more important than revolution, perhaps markets, liberty.

And I think the list isn't very much longer. So, to have a comprehensive analysis of revolution as a concept over the stretch of time that Dan ambitiously covers is pretty remarkable. And to say something new and fresh in a literature that's about 2,000 years old, judging by the book, is also pretty remarkable.

So please join me. Warm welcome. Dan Edelstein, Cumming Hoover Senior Fellow.

>> Dan Edelstein: Thanks, this is, as Steve mentioned, my fourth book on this sort of broad topic. And in some respects, this is a book that, embarrassingly, I've been working on for over a decade, actually, ever since I finished my first book, which was on the terror of the French Revolution.

And at that time I was struggling with this, not really a problem, but trying to understand almost something obvious. And the obvious thing was that the French Revolution has this sort of world historical quality that I think most people would agree is kind of missing from the American Revolution.

That the French Revolution just was such a transformative moment in history, would be the model for so many other revolutions. And yet also is coming right on the heels of the American Revolution, has all these obvious ties to the American Revolution, even some of the same personnel. Lafayette Jefferson and so I was wondering, well, what makes it so different and why did the French Revolution have such a broader, almost bomb crater than the American Revolution?

And to some extent, as I always remind my Americanist colleagues, in the 18th century, America was this sort of provincial backwater on the other side of the Atlantic. France was the center of the world, Paris was the capital of the world and so the fact that the revolution happened in France was in and of itself that much more dramatic.

But of course, that only scratches the surface of this. And so as I was trying to find some reasons to understand this challenge, I started exploring more the political scientific literature on revolution and just ended up feeling very discontented with it. Sort of the dominant structure story at the time seemed to be that French Revolution was the first of the social revolutions.

Before that, something like the American Revolution was more political, sort of the Theta Skocol story. And it just that seemed like a very impoverished explanation for me both because I think actually, if you look closely, the American Revolution had a very of clear social dimension as well. Maybe it wanted to preserve a certain vision of society, but that also means that it's thinking about social issues in the same way.

And also it seemed to not capture the incredible political excitement around the French Revolution and some of the energy there. So I started thinking about this more, and then I sort of realized that there were two really important and telling clues that I built this current book on.

The first is that the Americans don't really talk about revolution. They don't talk. The expression American Revolution is very rare in the first decade of what we now call the American Revolution. It's something that gets retrospectively applied to it, but they're not writing to each other saying, hey, this revolution that we're doing is pretty awesome, isn't it?

If anything, they still seem to view the word revolution as a bad thing, something you kind of want to avoid. Thomas Paine does not use the word revolution in common sense, except for one time, and it's in reference to the Glorious Revolution. And indeed, the only American Founding Father who does talk about revolution to any degree is Adams.

And that's quite interesting also because Adams is often, I think, somewhat unfairly seen as the more conservative of the Founding Fathers. And if you trace it, like, why does Adams talk about revolution more than anyone else? Again, it's because he sees this really strong parallel between 1775, 1776, and the glorious Revolution.

And that's the framework he brings when he starts to use the word revolution. It's actually to say we, the American colonists, are being faithful to the, quote, revolution principles that have guided British politics since 1688. And so it is, in effect, a conservative move that he's making to say, you can't criticize us.

We're just actually being more faithful than you, the British, are, to your policies. So that was one interesting thing. Why is it that the French, from the very beginning Vive la revolution. They're all in. They're embracing this term. They're embracing this concept. They're calling it the French Revolution from day one.

So that was an interesting clue, like, what's changed there? And then the other realization was that clearly this has something to do with how they think about history and that the Americans and the French don't simply see revolutions differently, they see history differently. And that's really that was the insight that led me to write this book, that there's something that happens in 18th century France that modifies the general narratives of history that most people have.

And in fact, it's not anything really surprising. It's during the 18th century, a number of the, the French philosoph, though not all start to advance a new vision of history which we would today just refer to as the theory of progress. And in this, in this understanding, history is not, you know, as one British historian later put it, one damn thing after another, but is actually a slow, gradual accumulation of knowledge where things build on each other.

And that in this regard, the, you know, 18th century French are more advanced than the Romans had been or even than the Italian Renaissance had been. And on top of that, the 19th century French would be even greater. And that if you sort of embrace this vision of history, you are going to suddenly get way ahead of everyone else.

These are things we're very familiar with. It's sort of Chakrabarti has talked about how this is actually part of the whole civilizing mission of Europe that the Indians, for instance, have to be in what he calls the waiting room of history until they can progress to being in charge of their own affairs.

But this vision of progressive history or what I call the modern doctrine of progress emerges in 18th century France. And I can say more about why that happens and how it differs from other visions of history that came before. But for now, I'll leave it there. Now, in this model of history, you're actually getting somewhere.

Indeed, this is where we get notions like the end of history, that maybe you'll get to the point where everyone is finally agreed. And that seems to be what's underpinning this modern doctrine of progress. It's the idea that eventually reason will triumph, justice will triumph, and there will be no more politics because everyone will be rational.

Everyone will agree there's only one set of laws of physics, one set of Newtonian laws, in the same way there'll be one set of political laws. That's the idea that emerges in these progressive modern circles. People like Turgot, the famous Controller-General of Finances, and before him, I mean, some lesser known French figures.

But the Abbe de Saint Pierre is a key figure here as well. So this is premised not only on the idea of material gains and benefits, but actually of all society coming to a single agreement, a consensus about all the problems in the world. That's sort of the great modern hope.

And in this hope, revolution simply becomes the portal into which we will arrive at this glorious future, the future, the revolution to come, will lead us to this perfect future where all disagreements will have disappeared. So revolution becomes the solution to our political and social problems. And I realized that to really show how radical that new idea was, I actually had to go all the way back to the ancient Greeks, thanks to a seminar I took with Josh Ober.

And realizing that what this was reversing was in fact the classical view, not only of revolution, but also of history. And it's a classical view that you, I think, see perhaps for the first time in its sort of clearest shape in Thucydides. So if you remember Thucydides's famous description of the revolution or stasis in Corcyra is the worst thing that can possibly happen to a polis.

It is the unnatural state par excellence. Fathers killing sons, words losing their meanings, the world turned upside down. And the lesson that Thucydides takes from this, and that most philosophers, political thinkers, after Thucydides will repeat, is that we are doomed to this unless we can find some solution.

Because human nature is always the same. That's sort of the premise of classical political philosophy. That's why we study history. Because if you study history, you learn how people always will be. We're always gonna sort of have the same natural impulses. And so because there's not going to be any end of history, because we don't make progress as a species, human nature does not improve.

In this classical view, revolutions are always gonna be hor events, completely destructive and devastating. And so what you really want to figure out, and this becomes the purpose of political philosophy, really from Aristotle all the way up to Adams, I would argue, is how do you design a political state that is revolution proof?

So actually, the first half of this book is really on the history of constitutionalism. It's history of how theories of balanced constitution are developed at various points in history. Rome, then in republican Florence, and then 17th century England especially, and then finally, 18th century United States. But because the reason people are so wedded to this view of checks and balances, of finding a balance of constitutional order, is so that they can prevent revolutions from happening.

And the reason why it takes a balanced constitution to prevent revolutions from happening is because in this classical view, where not only you're not going to make any progress, historically speaking, but you're also never going to get rid of social disagreements. There will always be disagreements between the, the wealthy and the poor, the creditors or the debtors.

And therefore, your best hope is simply to balance these interests so that nobody wins. And we're kind of in this stalemate that prevents revolution. And so it's actually a pretty pessimistic view. Constitutionalism in this well balanced way is not supposed to do a lot. Actually, there's a great passage in Tacitus where it's like when people start passing a lot of laws, you know that it's over.

That's a really bad sign. It's supposed to be preserving the status quo. That's actually what it's designed to do. And today, people say, congressional gridlock, it's terrible. It's like, no, that's actually working exactly how it was meant to work. And so that's why I ended up having to write this story from Thucydides to Lenin.

Because in a way, even to understand what makes the French Revolution sort of the world historical event that Hegel and others saw it as is that it breaks with this classical understanding of history, of revolution, and even of human nature. By premising that humans are going to reach this stage where there will be no disagreements, justice will finally rule, and we will have reached this sort of end of history state.

Now, of course, didn't exactly turn out that way. And I think that sort of the last chapters of the book explore how the specificity of modern revolutionary violence is itself connected to the failure of this modern view, because. Because what you start to see already in the French Revolution is that when people don't naturally all come to a consensus about what is the proper structure of the French government or any political issue, rather than saying, yeah, we don't agree on everything and that's why we have this constitutional system that's supposed to help us figure out our disagreements.

No, then it becomes, well, if we don't agree, then clearly something's wrong with you. You must be either error prone or filled with superstition or worse, unnatural and fit only to be destroyed. So that was actually what I had sort of worked on in my first book on the Terror is the way in which Jacobin political leaders invoke these ideas of natural law that are actually just there in Locke and others who we think of as more liberal theorists of law.

But there was always this caveat that those who do not follow natural law should be destroyed. That is sort of the fundamental basis that if we cannot, if we cannot have a system where, based on our natural reason, we all recognize what nature is telling us as morally correct, then something's wrong with you, and then we have to just eliminate you.

And then that sort of becomes the modern vision on steroids. And I'll just maybe end my opening remarks by pointing out that I think that that's what accounts for the tragedy of the modern revolution, is that the American Revolution was actually probably almost as violent as the French Revolution.

Most of the violence actually happened before. So I sort of joke that the Americans had their terror before the revolution. If you look at the treatment of loyalists, etc, and then the violence, the way that they took during the war was atrocious as well. But what the Americans never did was go after other revolutionaries.

They might have hated each other, but they did not commit political violence against each other. And that's what would become the hallmark of modern revolutions, to paraphrase Hobbes, the revolutionary is a wolf to other revolutionaries. This is already recognized in the French Revolution, right, the famous line by Virginia, the Girondins, the Revolution is like Saturn, it devours its children.

And I think that to explain the specificity of revolutionary violence, you have to understand that it stems from this aporia of disagreement that in a revolutionary context, disagreement becomes impossible. Or as Trotsky would say, nobody can be wrong against the party. There can only be one truth. And if you do not fall in line, then something must be done with you.

Something must be wrong with you. And then the last thing I'd say is that of course they're then stuck with this problem. It's like, well, how do they figure out what is the revolutionary truth? Who gets to decide? How do we know what is just, what is correct?

And that's where I suggest that the other common feature of these modern revolutions, which sort of commonly referred to as the cult of personality, is actually almost more of a structural solution to this problem of not being able to have a system in which people disagree. In the end, you need somebody to make the decision.

That's why the last chapter is called Revolutionary Leviathans, there has to be somebody who makes the decision. And revolutions in this modern incarnation crave a Leviathan, so maybe I'll stop there.

>> Stephen Kotkin: Okay, Dan, so I think what you're trying to tell us, again, you'll correct me if I get this wrong, right, it was often seen that outcomes like Napoleon or Stalin were deformations of the revolutionary process.

In other words, things should have come out better, and somehow, through circumstance or a person's individual agency, ambition produced that Leviathan individual that you just alluded to, that you concluded to. So Napoleon deformation rather than culmination and you're, it seems like you're on the culmination side, not in the sense that it makes the revolution consolidated, but that this process of delegitimizing politics produces a conundrum for which this is the solution.

Did I get that right?

>> Dan Edelstein: Absolutely.

>> Stephen Kotkin: So we would then expect just about every case of revolution to push in this direction, whether it achieves this way out of the dilemma or not. This is the dynamic that we would expect, so that's what we might call a negative view of revolutionary process and the desirability of revolution.

Is that where we're coming out on your idea? Revolution is a positive for a great, I would say the majority of the time since the French Revolution, it seems seen as a step forward as necessary, as hopeful, as containing possible futures that are superior. But if you're right on this Leviathan problem, then that would be problematic to have a hopeful view of revolution.

Did I get that right?

>> Dan Edelstein: Absolutely. And I think you see precisely that, you know, that tension in just about every modern revolution of the 19th and 20th centuries, that the sort of the incredible excitement, enthusiasm that happens at that moment precisely because of this sense of unlimited future possibility.

But you can't have multiple perfect futures, right? If you believe that everything's going to get resolved, then that's a very unidirectional way of imagining progress and I think it's also fueled, especially in the 19th century by all of these utopian writers who are incredibly detailed about what this great future is going to look like.

Somebody like the guy, I'm sorry, I'm having a brain moment, Fourier, who has the phalansteries idea. He actually tells you the dimensions of the hallways in his phalansteries, this is a science of the future that they're all envisaging. And so it's actually very anti pluralistic, I think that's what it comes down to.

>> Stephen Kotkin: So we have all the cases, we know Napoleon, Stalin, Mao and then we could go on to the smaller version, smaller only in the number of victims and not in their ambitions. Are there cases where it turned out differently so that they were able to resolve the problem without recourse to the Napoleonic outcome?

>> Dan Edelstein: Well, I think there were a number of revolutions that fell back on the older constitutional model. So many of the, for instance, Spanish American revolutions were very wary of the French version. They didn't like that at all. And in fact they, they wanted to be more like the American Revolution.

And they, they saw a lot of parallels, of course, you know, kind of these revolutions for independence. But I think what's tricky is that, and there were other liberal revolutions in Europe also in the 19th century. But I think what's tricky is that the modern doctrine of progress as a historical vision really caught on.

And so the liberals were kind of fighting with one hand behind their back. They're like, you know, this is a good place to stop

>> Stephen Kotkin: classical liberals.

>> Dan Edelstein: Classical liberals, yeah. As opposed to sort of the more revolutionary progressives, they would say. And you see this, for instance, in 1830.

So they get rid of the Bourbons a second time. This is in France. And you have this moment of sort of uncertainty. Is France going to go back to a republic? Is it going to be a constitutional monarchy? And they try to have a constitutional monarchy with a very non authoritarian figure like Louis Philippe is not a particularly powerful monarch.

It's supposed to be really a parliamentary monarchy. The problem though is that where do all these great hopes and expectations for the glorious future go? And so, you know, within two years you have barricades in Paris again. And the July monarchy is really a ticking time bomb until 1848, what does that culminate in another Napoleon, finally taking over?

So I think the problem is, so long as there's a deep-rooted, almost cultural belief that this amazing, wonderful future is around the corner. That's where the structural push towards the authoritarian figure often will derail any attempts to have a more pluralistic parliamentary structure.

>> Stephen Kotkin: So one final question before we open it up.

So, I mean, this looks like an eternal problem that we've inherited of trying to set separate the hopes for a better future from the elimination of politics as abnormal or as detrimental. So holding on to hopes for a better future while recognizing that politics is desirable, it's normal and desirable to have politics and to want to eliminate politics like Lenin and the rest of them did that.

That's the problem. So is this dilemma manageable? Can we figure out how to keep some type of hope for a better future while accepting the constitutionalism and the limits on what state power or executive power can achieve or what it's allowed to do?

>> Dan Edelstein: Yeah, I don't think that it's an incommensurable problem.

I think that it's perfectly possible to be hopeful for some forms of social change while recognizing that there's a political process that is going to make this maybe more difficult than if you had a Leviathan figure who could simply wave a wand. But I think that what I've realized and what I've tried to emphasize in the book is just how it does require giving up on a certain vision of history that I think maybe all of us also have kind of internalized a little.

There's just an expectation that, you know, the latest iPhone is more powerful than the next one and that, you know, we're going to have flying cars eventually. And that's sort of little by little trickles into sort of a sense that, not just technologically, but even morally and at sort of an existential level, we're making progress.

So I think being able to separate out, we could make progress on this particular problem or on this issue. But as a species, we are probably not changing or progressing much, I think would get to the place you're gesturing towards.

>> Stephen Kotkin: All right, we'll continue with the brain food while waiting for the sustenance to arrive, which is coming shortly.

And now we'll go to the live studio audience. We'll start from the top.

>> Steven J. Davis: Thanks, really fascinating discussion. I wanted to push back on one aspect of these, of what you said in particular, including your last response to Steve. So you laid out this classical vision of humans and progress, or Stacey's, and you laid out the modern view associated with the French Revolution.

But of course, another view which I guess I associate with the Scottish Enlightenment, which I understand to accept the classical view of human nature, but recognize that culture, institutions, even policies and norms can channel human nature and society in more or less productive ways. And that view doesn't discount the possibility of continual progress.

It takes a much dimmer view of revolution, of course, but so I don't think those. The two maybe do much more of this in the book. I'm sure you do. Those two polar alternative you sketched out are not the only ones that are possible, nor that have manifested themselves.

The American Revolution kind of is more in the Scottish Enlightenment mold. But what I don't understand in my limited grasp of history is why the French and the French Revolution modern view that you described had such a strong hold in some parts of the world, including France, and in much of the intellectual class.

And the more Scottish Enlightenment view, which has room for pluralism and doesn't adopt this premise that there's one best outcome for all. And so that kind of pushes you in the direction of individual liberty, rule of law. We kind of all want to get along and make our own progress in our own ways.

So can you erase some of my ignorance as to why. Why that modern French Enlightenment view was so powerful and these other alternatives that were also being discussed at the time and had some real world manifestations seem to be less influential then and even now?

>> Dan Edelstein: Yeah, it's a great question.

I do think that there's, there's a way in which the French Enlightenment was fashionable. And I mean that almost in a literal sense, like the same way that French was the language spoken across Europe, that French fashions would spread throughout Europe, the same way they would be picking up the latest Voltaire and other, you know, bestsellers in France.

And so there was just this oversized presence of French culture and French ideas throughout Europe and Spanish America as well. I also think that there is a sort of British exception to all this that I think has to do with the different narratives of history that emerge in the British Isles.

I think you see this already in the 18th century. The way in which the Glorious Revolution serves as the touchstone for a lot of British political thought and does not have this forward looking aspect to it. But is still sort of a sense that, well, we Brits, we're really great because we figured it out and our constitution is better than anyone else's and all we have to do now is stick to it, right?

So it's interesting. Even if you sort of look at like the more progressive figures in England in the 18th century, they're always going back to 1688. I also think that there's a bit of a, I mean, it depends when we're talking about Scottish Enlightenment. There's lots of different people here.

But I think a common mistake I've seen is people say, well, the Scots believe in progress, but it wasn't sort of the same utop. Utopian style, progress as the French. But actually I think the Scottish had a very classical idea of progress. So you know, what are they famous for?

The stadial view of history, right, of like you start with savages, and you get to barbarians, and you end up at the civilization. You find that in Cicero and Lucretius. It's not a modern idea at all. And in fact, when they're talking about civilization in that sense, they're not saying, and we the Scots or the British have sort of come to a higher point of civilization.

They're saying, no, we're like the Romans and the Greeks and then we kind of stop here. And that's exactly what someone like Lucretius would say in his anthropology. It's like, well, we didn't used to have all these art and life used to be really rough. But now that we're like Rome, age of Augustus, you can't surpass that this.

And so I think I still see that a lot in the Scottish Enlightenment, that there's not really much further to go. But it's also not necessarily a vision of continual historical progress. But again, there's a lot of different people we could look at here.

>> Stephen Kotkin: We've got Phil Zelko, then Anthony, then Josh and then Norm.

>> Philip Zelikow: So this is terrific. And my first really fundamental question to put very simply is, is liberty revolutionary? Yeah, right, so I was converted long ago by R.R. Palmer. All right,

>> Dan Edelstein: great historian.

>> Philip Zelikow: And so, I think liberty in the earlier, in the 18th century and including even in the Scottish Enlightenment is actually regarded as a somewhat conservative concept.

That is privileges and liberties that are being protected. There is a point though at which the concept of liberty is expanding to handle modernity. And it very much is by the end of the 18th century, it very much includes liberty of thought, people being liberal minded, opposition to religious dogma, openness to merit, and therefore takes on this extraordinary role opposing hereditary aristocracy which it equates with tyranny.

And then of course it's then regarding the king and the colonies, of course as basically exploiting modernity to create new mercantile monopolies and a royal tyranny, etc. All right, so there's an argument then that the advocates of liberty by the late 18th and early 19th century are actually regarding liberty as a revolutionary concept.

But there's also a sense in which it is a revolution, but it's kind of a one time revolution because once you install the system of ordered liberty, ordered liberty copes with modernity. And this is in a way where I think you're setting up this really interesting argument. It's because actually for a while there revolution is this enormously popular positive concept that's then applied to all these technological and economic phenomena.

Market revolution, industrial revolution, many things and but then there is this question is since there's all this technological and economic change is gee, liberty actually can't cope with modernity. You need a stronger theory of progress than liberty can handle. And therefore, people are trying to adopt the mantle of the only true revolution is the continuing revolution.

That then requires the kind of, shall we say purposeful direction that you're alluding to. So I kind of start then from this fundamental question is do you regard liberty as revolutionary in order to then I end up with can. Can revolutionary liberty cope with modernity? Or is its claim is that it's a one shot and then you allow, you've created a system of pragmatic evolution that copes.

And then the continuing as you kind of follow the arc of your story these are people who are you nope, it doesn't cope. You need something else is But I don't. I'm trying to relate, that's an argument that actually flows from your provocation. And I don't know whether I'm disagreeing with you or agreeing with you.

>> Dan Edelstein: I think we're pretty much in agreement. I guess I would add that I think this connection between revolution and liberty goes back to antiquity. I mean one thing I didn't say is that in the ancient, despite the phobia of revolution that you find in ancient writers, there's always one exception.

That's the revolution that brings about the well balanced state. And the classic example of that would be the expulsion of the Tarquins and the establishment of the Roman Republic. And the first word of book two of Livy's History of Rome which begins with the tells the story of the Roman republic is liberry.

So freedom is the moment when the republic is founded and this will become central to Roman political thought as well. And I think from there it will carry into early modern thinking about freedom and revolution. So, Machiavelli is big on liberty. That's what the discourses are all about.

And it will carry all the way up into the French Revolution. After all, liberte, egalite, fraternity. It's the there from the beginning. But I think you're totally correct that as revolution even in the French case evolves it's not seen as enough. It actually starts to seem almost as what's impeding the revolution from making progress.

And so liberty starts to get downplayed as a revolutionary value. And then, you know, Marx would then, you know, on the Jewish question, liberty just becomes a bourgeois ideology that's not really about true human emancipation. It's about this sort of false consciousness that happens in the.

>> Philip Zelikow: So then in the classical tradition, revolution can be good if it attains the necessary measure of liberty?

>> Dan Edelstein: Yes and no, because. So, I didn't talk about my favorite class classical thinker who's kind of the hero of my book and that's Polybius. So, in Polybius version, all of the different regimes are kind of in a cycle, what he calls the anancy closes. So you know, you start with the king, the king becomes bad, you get a tyrant, eventually there's a revolution and it's the leading men of the state, aristocracy, you know, yada, yada, yada.

Democracy gets overturned and you're back where you started. And this sort of describe it as like the Sisyphean wheel of history for the ancients where it's not great to go from one to the other because you're just gonna keep going around the wheel. So, the only good revolution is getting off the wheel.

And you do that by having a well balanced state that combines all three of the pure models. So he'll say the Roman Republic is great because it's actually a triple state. It's a monarchy, an aristocracy and a democracy all into one. So that becomes the solution. That's the good kind of liberty.

He doesn't actually describe it as a free state, but Cicero will come along and say that's true liberty, but otherwise in the classical version, liberty is usually just associated with democracy. And most of these guys don't think democracy is a great idea. So it will become connected to the good revolution, sort of through the Roman example.

>> Stephen Kotkin: There's more to explore there but let's widen the conversation. Anthony.

>> Anthony: If I understand this master narrative of interaction between revolution and. And ideas about history and antiquity, the violence, the rupture, they lead people to believe that we need to study history because there's a fixed human nature.

And then the French Revolution comes and there's this scramble for understanding, all the rupture and of course, industrialization, all that. And then it's more that we need to study history to understand change. And for perhaps one way to reconcile it with Hegel is that it's in human nature that we're meant to change, that we're meant to go through these phases of development until we attain the end of the story, if that's right, it seems that the revolutionaries of the late modern era, Marx and his followers, the political leaders and other revolutionaries, there's a tension in their thought where they think revolution and emancipation, the end of history, this is all inevitable, but people should listen to us so we can kinda push it along, right?

So it's going to happen, but maybe it won't happen unless you listen to me and you follow me. Is that what I take to be a bit of a paradox? But is that something that all of these, that many of these revolutionaries think, is it distinct to the late modern era?

Is this a tension they grapple with not just the theorists, but the leaders? And are there is this foreshadowed a bit even before the late modern era?

>> Dan Edelstein: Yeah, no, I think you're absolutely right. And of course that's sort of central to Leninism, right? Like the people aren't just going to radicalize themselves, but you see it all the way back in the French Revolution.

There's this conspiracy that happened in 1795 called the Babeuf conspiracy, and it's during the Directory, and it's the first communist revolution really and Marx in fact recognizes it. They want to abolish private property, but then they're confronted with this challenge, which is that, okay, so we seize power, and of course we want to be democratic because that's the future.

Right, but the people aren't going to be with us right away. So how deal with this? And you end up having what I describe as the future perfect politics, sort of punning on the grammatical form. We will have achieved what we want. And then what we have done will have been justified, meaning that we will have to have a dictator who will get us there and get the people there too.

And it's the same logic that you find in Marx. When Marx has the famous line about the permanence of the revolution and the class dictatorship of the proletariat. It's in this temporal way, it's the necessary transit point he says, to get to the next phase where everything will be sorted out.

But I think that to kind of pun on Augustine like that, give us democracy, but not yet is really baked into this sort of modern revolutionary attitude.

>> Stephen Kotkin: Josh.

>> Josh: Thanks, dad, and much enjoyed our conversations along the way. So this is the question is about, is there a distinction to be made between progress and growth because as you point out, it's pretty common in the classical thought.

Imagine that back in the deep past things were rather small and poor, and now things are much larger and wealthier, better in material sort of way. And at least if we then sort of jump forward maybe to the Scottish Enlightenment, I think then the idea of at least a continued material advance is certainly possible.

Factory isn't the last development, I think, for Smith, but then there's sort of a disjunction between material growth in the material circumstances of our lives, perhaps even the technologies that we use, military technologies, various other kind of building techniques and so on. And the idea of this kind of moral progress towards the final end.

And it's really the sort of idea that we can progress morally to a perfectly just world, that the humans will transcend their current sort of bad condition and come to a best sort of condition, a fully just condition of perfection, of our lives together, our social existence. That seems to be what really drives that revolutionary need to destroy the counter revolutionaries who are in our way.

So just the basic question is, is there a story to be told in which that the kind of growth question is dis sort of is not attached to the moral progress question. And does that help to answer Steve's.

>> Dan Edelstein: No, I think that's a really helpful distinction. absolutely.

And I think what's striking is how that becomes a distinction that people have a hard time keeping in mind. Right, so even Robespierre has this famous speech, speech where he'll say half the revolution of the world has been done, the other half remains the revolution of the morals and the mind.

And I think it does come out of this. That's sort of the whole premise of this 18th century, pre revolutionary doctrine of progress, which is that Voltaire is always talking about the revolution in the minds, it's this moral, almost a kind of religious reformation that they have in mind.

And indeed, that's one of the examples that Voltaire will give of a prior revolution was the Reformation and you see this Even in the 19th century, people are always even sort of more liberal in the sort of classical sense. Bourgeois defenders who are not at all in favor of revolution in this sort of strong progressive sense.

They're always slipping into this sense of a kind of utopian transformation of humanity too. The one thing I'll add about antiquity, though, is that I think what's different there is that people like Lucretius and others, they always have these examples of the people who have not made that change, right?

So the inculci, those who are still on the other side of civilization. And so it tends to feel more like a binary, right, that you can either be, you know, off there in the forests of Germania, jumping in rivers at a young age, or you can be like the good Gauls who have figured out that they too can be civilized and like us, but then it kind of ends, right?

So the continuous growth, maybe there, that is sort of perhaps what the Scots figure out, right? That there can be this more gradual wealth of nations and prosperity that is not indexed to moral progress.

>> Stephen Kotkin: Norman.

>> Norman: Thank you, Dan. Nice to see you here. I kept thinking during your presentation about sort of other revolutions that are anti-colonial revolutions, that are national revolutions, the Polish Revolutions of the 19th century, in which elites within the Polish lands or outside Czartoryski is a famous link between the French Revolution, I think, in the 1830s, Polish Revolution.

So how does that fit into your kind of sense of how revolution takes place? These are not social revolutions.

>> Dan Edelstein: Right.

>> Norman: In other words, there's a link, a long duray of social revolutions which we've always studied in Ukraine, Britain, and others that go up through Lenin, and the Chinese, and so on.

But how do national revolutions and anti-colonial revolutions fit into this very capacious term? I mean, it is an important term, but it's also so capacious, as Philip was pointing out too, in other ways that, you know, can be bothersome. And then I was thinking about the American Revolution too, which is essentially an anti colonial revolution, establishing elites that are already there.

I mean, they have social components, right? I mean, even the Polish revolutions have social components. Marx loved the Polish revolutions because it was anti Russian. But how does that fit in this kind of trajectory, this long duray that you're painting for us?

>> Dan Edelstein: Great question. So I, I do actually distinguish between sort of two legacies of the French Revolution.

One I call the liberal legacy and the other the progressive legacy. And, and the liberal legacy is exactly this sort of Polish nationalism. It's all of, you know, it's Spain, Cadiz, it's Portugal, and it's at first most of the Spanish American revolutions as well. And I sort of see that as a kind of a soft modernism in the sense that they still believe that like this is the future.

The future is to have liberal constitutional government, and sort of, if you're not on board with that, then you're a reactionary. And so it's sort of a softer version of the doctrine of progress that sees liberalism sort of as the nec plus ultra. I actually have a chapter where I argue that Napoleon is the founder of this, because Napoleon's whole deal is to say, look, politics is too messy.

All you really want are rights, so I'll give you rights at least sometimes, and I'll take care of politics and then you can just go about your business. And that actually sort of in many respects will become the model for a lot of European liberals, where democracy, we don't really want that, give People rights and leave politics to the elites.

>> Dan Edelstein: Yeah, exactly. For the most part. For the most part, yeah. But then it's always in tension with the more progressive who are saying, like, what kind of, you know, vision of history is this? Like, we want the second half as well. Although I would say with the Americans, I mean, I'm very convinced by Eric Nelson's book called the Royalist Revolution that the Americans are still looking to the British Constitution as the best you could do.

And I know that some Americanists bristle at that idea, but it seems pretty convincing to me.

>> Norman: That's sort of what I mean, in that sense, the French Revolution, American Revolution, at least. Polar opposites.

>> Dan Edelstein: Yeah, exactly.

>> Stephen Kotkin: So if I can triangulate, we're about to close the formal part of our discussion.

You'll get the sustenance in a moment. So I think both Steve Davis and Phil Zelikow and some others are pushing you on this. So this was my primitive understanding before I read the book. You have constitutionalism, classical liberalism, separation of powers, limits on executive power in some fashion before the modern social era.

And then countries that didn't have that institutional achievement, they didn't manage to introduce constitutional rule, separation of powers, limits on executive power, not limits that are circumstantial, but limits that are institutional and formal. It's too late, because now we're in the modern era with the social revolution. And so the former minister of interior in the Russian case hates the constitutionalists.

Of course, he's pro autocracy, but he hates the constitutionalists because he thinks they don't understand history, that they are going to take the czar down in order to get a constitutional republic or even constitutional monarchy. But they're gonna be swept aside by the social revolution that's gonna destroy any hope of liberty.

And so they're fools to oppose the czar, because they're opening up the door to a social revolution that's gonna wipe them out. And if you look at this epoch, I mean, Frank has written about this epoch, right? The China case, the Mexico case, the Iranian case, the Portuguese case, all these cases between about 1910 and 1925 have an attempted constitutional revolution that fails.

There's no example where there's a successful constitutional revolution. Mexico, China, they're all slightly different, but they have this pattern of the liberals in the classical sense. The constitutionals don't have a wide enough social base, and they can't impose the institutions to limit their own power, as it were, successfully, because they're facing the masses and the social revolution, whether in the form of strikes or whatever.

And so liberty and revolution become as it were enemies even though liberty was originally a revolutionary concept to break the privileges of old regime of people born into a certain status in life. So liberty has this moment of being revolutionary but then discovering that revolution is dangerous for liberty.

Sort of what the Scots were onto in the 18th century, sort of what Phil Zelikow was pushing at. And so you pin the tail on the donkey of progressive understandings of history, all right? The so called arc of history bending a certain way. And so that's the enemy.

In other words, if, if we allow the progressives into the room, they take over Stanford or whatever the metaphor you prefer, right before you blink your eye. But what other people are suggesting is that there's this social component, not solely a progressive theory of history, of incorporating the masses into a polity, not just making a constitutional order but making a constitutional.

Constitutional order in which peasants or farmers and industrial workers and artisans are part of the polity. They, they are citizens in the full sense, whether they own property or not. Right. And everybody's a citizen, including all of these people who might not be as educated, might not own property.

And so it's the social problem that swamps the constitutional orders. Not solely or even predominantly the idea, the concept of the progress, progressive notions that tell you you're only going to move in one direction. And listen to me, because you have no choice. That's the direction that history is going.

So how do we reconcile the intellectual history on the progress side, which is deep and fundamental? And I don't think any of us are going to deny its effects because we've been living through it with the social dimension? That was more my understanding before I entered into your framework.

>> Dan Edelstein: I'm reminded of what Marx says in 1848 when after the presidential election, which is that let the people vote and you get a Bonaparte. And I think what he's pointing out there is that in a empirical sense, the broad masses of society are not necessarily the ones who are pushing for the social transformation of the state.

They can actually be much more conservative. And I think the same probably holds true in the Russian case. The peasants are not fodder for the Bolsheviks.

>> Stephen Kotkin: No, unified Germany.

>> Dan Edelstein: Yeah.

>> Stephen Kotkin: This figures this out.

>> Dan Edelstein: Right.

>> Dan Edelstein: So as Raymond Aron put it, communism is the opium of the intellectuals, right?

And, and I think that this is, I, I do feel like this is more of a kind of intra intellectual elite story about which direction does the revolution go in and that most of the time the masses end up being kind of dragged along unwillingly. So not to say that ideas rule the world and that there are no social contexts here, but to me it does seem like there's a power, a scary and incredibly strong power to this idea of revolution that's going to lead us to a point where we just won't need politics anymore.

And it seems like that really drives a lot of the story.

>> Stephen Kotkin: Ladies and gentlemen, let's give it up, Dan Edelstein.

>> Dan Edelstein: Thank you. Thank you so much.

SPEAKER

Dan Edelstein is the William H. Bonsall Professor of French, and Professor of Political Science and History (by courtesy) at Stanford. He studied at the University of Geneva (BA) and the University of Pennsylvania (PhD). Revolution to Come is his fourth book on European intellectual and political history.

MODERATOR

In addition to his Hoover fellowship, Stephen Kotkin is a senior fellow at Stanford’s Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies. He is also the Birkelund Professor in History and International Affairs emeritus at the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs (formerly the Woodrow Wilson School), where he taught for 33 years. He earned his PhD at the University of California–Berkeley and has been conducting research in the Hoover Library & Archives for more than three decades.