- The Presidency

- Security & Defense

- Revitalizing History

In the realm of American politics, the notion of a “deal” has long carried a whiff of suspicion—conjuring images of smoke-filled rooms, cynical bargains, and horse-trading for personal advantage. Yet dealmaking, far from being a shameful deviation, is a core element of American presidential tradition. Throughout history, presidents have used bold, visionary “deals” to confront the nation’s toughest foreign and domestic challenges, demonstrating that negotiation and compromise are indispensable tools of leadership. Seen in this light, President Donald Trump’s “Big Beautiful Deal” rhetoric fits squarely into a proud legacy that stretches back more than a century, echoing a deeply American style of pragmatic leadership.

From Theodore Roosevelt’s Square Deal to Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal to Harry Truman’s Fair Deal, American presidents have embraced the language of dealmaking to signal transformational programs. These phrases were not mere marketing slogans; they expressed a willingness to broker agreements among competing social, economic, and political forces in the name of the national interest. Whether breaking up corporate monopolies, reviving a shattered economy, or expanding civil rights, these presidential “deals” carried the legitimacy of negotiation to bring about real reform. Trump’s invocation of his own “Big Beautiful Deal” belongs to this same presidential tradition, demonstrating that a negotiated path forward—however challenging—is not only normal but expected.

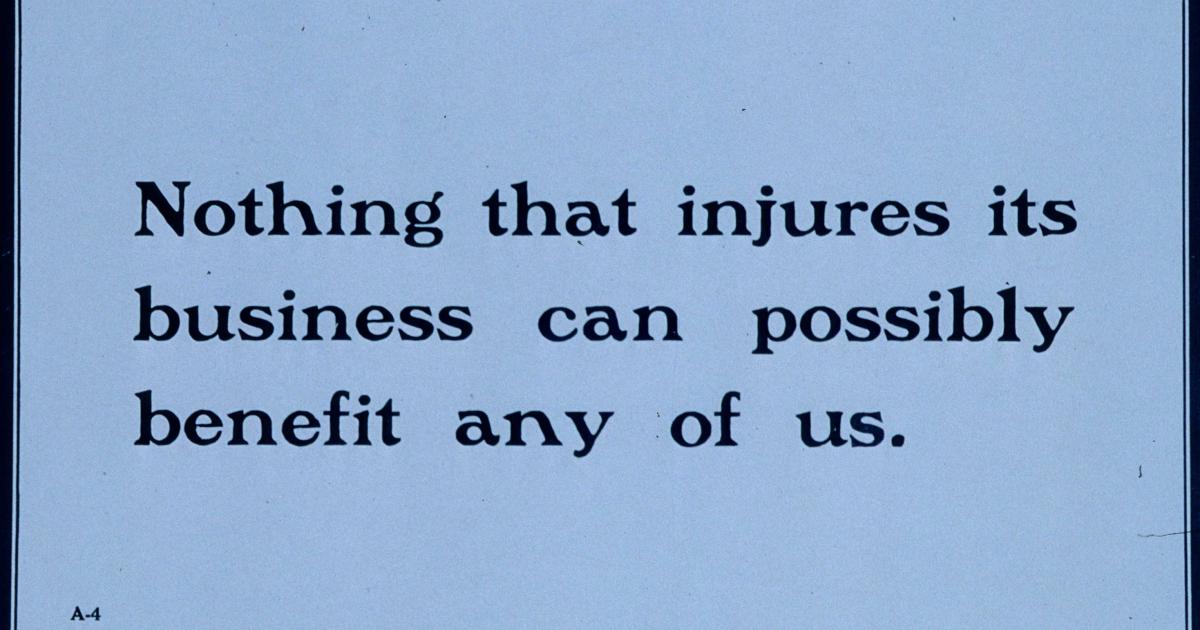

That said, the word “deal” has also been tainted in American history by some of its darker episodes. Americans have good reason to associate the term with backroom bargains, cynical alliances, and manipulative horse-trading. The presidential campaigns of the 19th and early 20th centuries showed these tendencies in full force. The contested election of 1876 between Rutherford Hayes and Samuel Tilden gave rise to the so-called Compromise of 1877, in which southern Democrats accepted Hayes’s presidency in return for the withdrawal of federal troops—effectively ending Reconstruction and dooming Black civil rights for generations. Similarly, the Republican convention of 1880 was an unseemly spectacle of delegates switching sides between Ulysses S. Grant and James Garfield. In 1948, Robert Taft’s allies clashed with Thomas Dewey’s faction in a swirl of backroom trades to secure the Republican nomination. These moments remind us that the dealmaking impulse, left unchecked, can devolve into a grubby, transactional cynicism.

Yet it would be a grave mistake to throw out the concept of deals altogether. Politics is, by nature, a forum for clashing interests, and it is often only through negotiation that progress can happen at all. When deals are infused with honesty, fairness, and a sense of the public good, they can transform society in a positive way. Theodore Roosevelt’s Square Deal consciously distinguished itself from “fast deals” made to benefit corporate bosses. Truman’s Fair Deal sought to advance social equity rather than reward “self-dealing” politicians. These adjectives—square, fair, new—matter enormously, because they signal that a deal is meant to lift up the common good rather than protect the powerful. In that spirit, deals deserve to be judged not merely on whether they exist, but on whether their substance is honorable and effective.

President Trump’s dealings with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un capture precisely this tension. As a lifelong negotiator, Trump boldly opened a diplomatic door that had been slammed shut for decades. His intention to broker a dramatic breakthrough in one of the world’s most dangerous nuclear standoffs showed the value of presidential dealmaking at its best—testing whether a historic settlement might be possible. But when Kim’s final offer failed to meet the essential interests of American security, Trump did not sign. He walked away, refusing to take a bad deal that could damage the country. However brash his style might have appeared, Trump upheld a longstanding presidential principle: good deals transform history, but bad deals must be rejected no matter how tempting the headlines.

The United States has been shaped by presidents who dared to make big, bold deals—and by those who knew when no deal at all was wiser. From the Square Deal to the New Deal to the Fair Deal, the nation has been steered by leaders who used negotiation to address social, economic, and security challenges. Far from being a dirty word, dealmaking has been an essential method of presidential governance, making the impossible possible through compromise and vision. Done right, a deal can build fairness, equity, and even peace. Donald Trump’s “Big Beautiful Deal” rhetoric was not an aberration, but rather another chapter in this American story, proving that while a good deal is good for America, a bad deal must be left on the table. That is, in the end, the true art of presidential leadership.