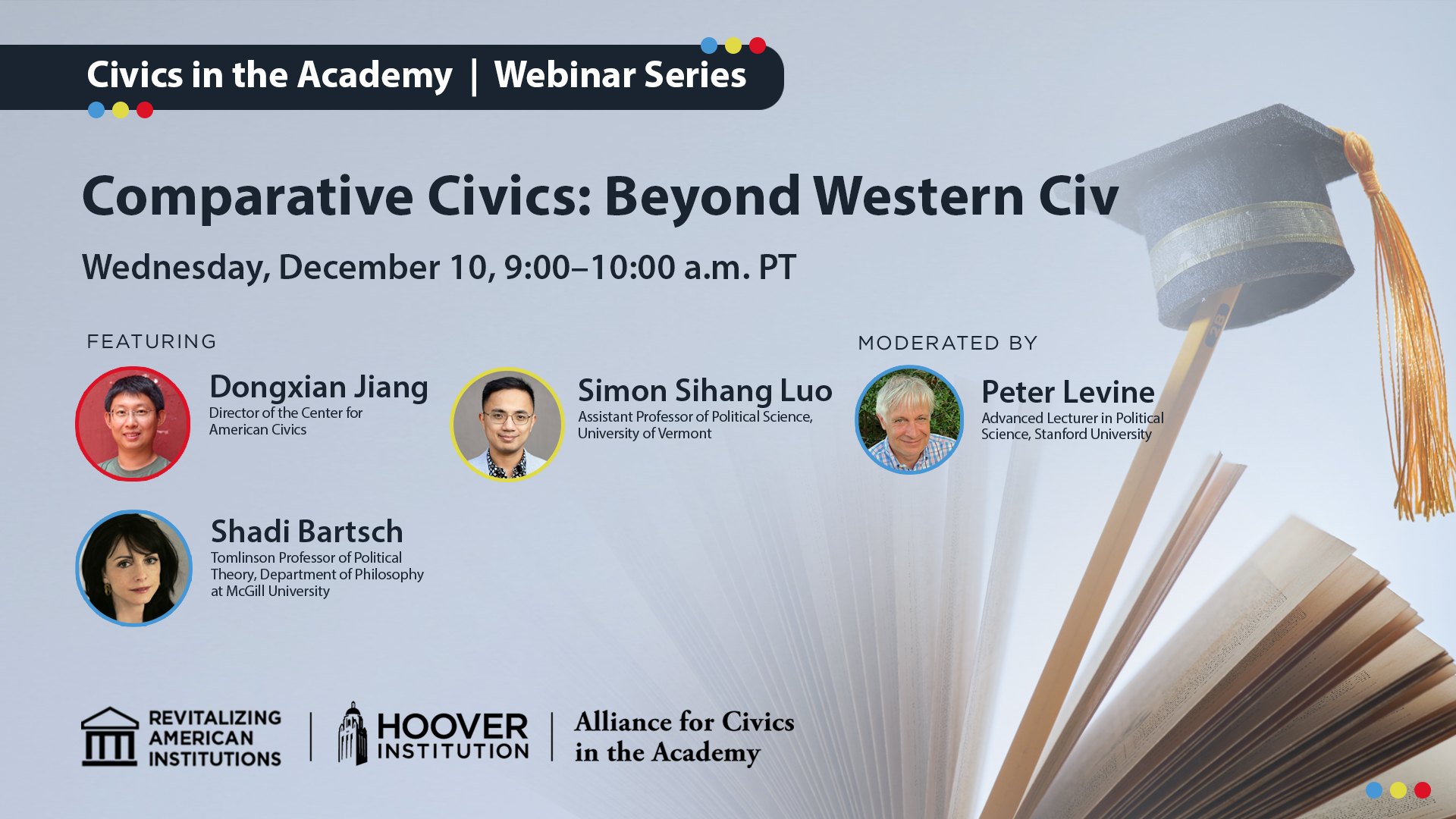

The Alliance for Civics in the Academy hosted "Comparative Civics: Beyond Western Civ" with Dongxian Jiang, Shadi Bartsch, Simon Sihang Luo, and Peter Levine on December 10, 2025, from 9:00-10:00 a.m. PT.

There is broad agreement that effective citizenship requires a firm understanding of the history and principles of the American constitutional system. But what about the insights, lessons, and perspectives that can be drawn from foreign contexts? How might the study of other societies–including those with autocratic systems or markedly different cultural traditions–enhance one’s preparation for effective American citizenship? This webinar explores what global perspectives can teach us about citizenship and democracy at home.

- Hi everyone, welcome to this webinar, comparative Civics Beyond Western Civilization. My name is Peter Levine, and I am a professor and associate dean at Tufts University at Art Tisch College of Civic Life. And I'm your moderator today, and this is one of a series of webinars put on by the Alliance for Civics in the academy or a CA. We had an inaugural webinar, which is more, more or less an introduction to the Alliance. And then after that we have a series of webinars that are substantive like this one. And so we'll, we'll share information about the whole series so you can join the a CA. The Alliance specifics in Academy was founded by a small group that our friend Josh Ober, Josiah Ober from Stanford, convened in April, 2024. And at that group, at that meeting, we agreed, the whole group agreed on some shared principles, which are on the Alliance website. And by January, 2025, we were an association and open to membership. And so anybody watching can look at the principles to make sure you agree and, and can join. It's a, it's really meant for people who teach civics in the academy. In other words, people who are part of civic education and higher education. But it's certainly open to you if you would like to join in that context. And one of a bunch of different things we do is offer webinars. So this one is entitled Comparative Civics Beyond Western Civ. I will say it's the way it's gelled, it's really focused on China. And, and maybe that wasn't in our mind when we had the title originally, but I think it's a, and so I should acknowledge that there's a lot of the world beyond China and what we call the West, which, which is something we can discuss what, what we should call the west. Anyway, there's much, there's many other consonants, but I, I actually think that the focus on China is gonna be very good idea because it is a focus. And so we should have one, be able to have one kind of organized conversation today with a number of colleagues who really know about China, which doesn't include me, but I'm delighted to be the moderator. So I'm, I'm gonna begin by just introducing our, our panelists. By the way, the slide, if you happen to see it was wrong, wrong titles, wrong even wrong institutional affiliation. So ignore those. But I'll tell you who we actually have here. So Shadi BCH is Helen Stein, professor of classics and a very experienced and famous translator, and was recently the director of the Institute on the Formation of Knowledge at the University of Chicago, both, both roles at the University of Chicago some other day. I wanna learn a lot more about the Institute on the formation of Knowledge. Her most recent book, Plato goes to China, the Greek Classics and Chinese nationalism, was Princeton University Press 2023. That's the hook for this conversation. Obviously. She also has two books in progress, 10 Tales from the Graveyard of Science, how Ancient Theory Shaped the Modern World with Scott Montgomery and Mutuality, the Meeting of Humanities and Science. Fascinating Topics. Don Chang is Assistant Professor of Chinese Studies in the Department of Languages and Cultures at Fordham University in New York. He's his research and teaching interest include comparative political theory, the history of Chinese and Asian political thought, intercultural dialogue and contemporary normative political theory. And he has a book Why China Needs Democracy. Incredible. The important title coming out with Prince and University Press soon it's in it's press. Simon Si is an assistant professor of public policy and global affairs program at the NY Young Technical Technological University in Singapore. He's a political theorist and intellectual historian. He's the lead PI of a research project entitled 1980, the Global Electoral Moment, China and Beyond. And he's working on a book manuscript that investigates the use and abuse of memories of the Chinese cultural revolution in intellectual, theoretical, and policy debates in post Mount China. And he was a postdoctoral fellow at the Stanford Civics Initiative at Stanford University, which is related to the A CA in many ways. We also are gonna be joined by Jesse Wong, who, whose video's not on yet, but that's fine. Oh, here she is. She can join us whenever she wants. She's a incredibly impressive undergrad in University of Chicago, majoring in anthropology and public policy doing significant research in rural China. And the idea with Jesse was to basically ask you to comment a little bit later in the conversation once you've heard these people talk about things that are relevant to your experience. So I'll, I'll, I'll call on you. Thanks for joining us. So, and we'll, the way this will work is we do have some questions for the panel, but I'm gonna make sure that we'll open it up to questions. We have something like 36 people in in live, live attendees, and more people will join later, but we'll give them an opportunity to ask questions and comment as well. So I guess I wanted to start a little bit autobiographically with how studying in either foreign countries and or the United States has shaped your experience thinking about civics and thinking perhaps in significantly about civics in the us. In other words, the topic is civics in the US but you've had the background experiences elsewhere. So maybe Dian, could we start with you? How did you, how did you experience sort of civic education in your own formation and what does, how does that make you think about civic education in the us?

- Sure, thank you. So I was actually also a postdoctoral associate in the civics in initiative program at Stanford. So I actually kind of, I, I was there from 2020 to 2022. And so the first time I saw the job announcement from SAI, I was like, okay, so what, this is the job about the moral foundations and moral and political foundations of democratic society. And I asked myself, should I apply for this? Because I obviously don't work on kind of contemporary western normative political theory. I work on comparative things, but because I was really desperate for a job, so I applied and I was surprised that kind of, I was admitted. So at that time I was like, okay, so this is a great moment, but on the other hand, what's the purpose? So is the United States right now in need of an authoritarian citizen to teach civics? So maybe this is the end of America. And so the reason I asked me this question was because I definitely didn't have any kind of experience in civics when I was in China, but I cannot say that China right now because I haven't been kind of, I haven't experienced the educational system for more than 10 years. But when I was in China, basically civics was about, Marxism was about kind of political ideology. This doesn't mean that the instructors of those classes, they did not have any kind of independent thinking. To the contrary, when I was in college, I suppose Simon would have similar kind of experience. Those Marxists, the instructors, they were actually yearly most critical. And they will teach us not only certain kind of basic textbook principles of Marxism, they would also say something very, very critical of the current regime and how to kind of perfect it maybe from a critical theory perspective, not necessarily from a liberal or democratic perspective. So I thought that my experience was in China, there is a tier system is definitely not every university would have the same freedom is not kind of the case that at every university you would be able to say the same things or learn the same things within the communist party system, within the education system. The idea is that, so if you are really at the top level of the elite class, then you would be assigned more freedom to explore something. So I was really lucky that kind of, I got some space of freedom to explore different ideas and to focus on political theory and to even hear Marxist scholars and instructors talking about kind of critical things from various different perspectives. But I'm not so sure whether this can be said to about other universities, maybe kind of the government would have some tighter controls of other universities. And so later when I came to the United States, I realized that, okay, so this is a place that from high school or from middle school, from primary school citizens were taught kind of civics, not in the way of indoctrination, but kind of in a way of cultivating critical thinking. So I thought that probably this is a place that I can contribute something important. And so right now I still don't know whether I would characterize myself as a instructor of civics. I would say that I'm a participant of liberal education rather than civics education, but I would think that there can be a lot of overlaps between civic education and liberal education. So basically that's my personal experience.

- And you're, you're coming, you're sort of at this point after fair amount of experience in the US your, your view is that the US civic education is non indoctrinating.

- So I

- I that's, that's a question that Americans debate. Yeah,

- Yeah.

- So whether education is indoctrinating or not,

- To be honest, actually kind of, I don't know. And I think America is definitely more diverse and the political system is more decentralized than China. So different states, red states, blue states, they would have different ideas about civic education, different levels of education. For example, middle school, high school, and, and college definitely kind of, their manifestations are different. So in China, I would say kind of is more unified. So the freedoms that given to you at higher level education or maybe higher level universities, these are kind of some implicit or tested freedom given to you rather than some legally guaranteed freedom. So I, I would say kind of these are the differences.

- I also was thinking when you mentioned that the professors at a, at a distinguished institution in China were often pushing against the assigned texts. That might be true at Stanford or Fordham as well. Yes, Simon, how about, how about you, your, your kind of trajectory and how you come into this question of teaching civics, especially in the us

- Thank you so much. I also did my undergrad in China. I was admitted to college as a liberal arts student first, and then ended up majoring in philosophy in particular political philosophy. And, and, and that's where I, I I, I had a bunch of very good professors. That's what got me interested in, in an academic career. And indeed it was, I found the history of political thought, particularly inspiring and stimulating for me. But at that moment, those were mostly intellectual inspirations. I was, I got hooked because I, I like the philosophical challenge. I like interpreting texts. I like working with, you know, smart people and smart minds in the history of thoughts. But then I moved to United States in 2015, I believe I have, sorry, 2013. I finished college, I enrolled in, in NYU as a master's student in politics. And that's, I think the, the, the environment. YU of most of us know that it's a university without the campus, and there are tons of stuff going on. And that's where I start seeing ideas translating into politics. When I was a student there, there were several different kinds of movements going on, including, for example, there was an adjunct movement defending their workplace and labor rights. And my, many of my professors were somewhat involved, some of them active, actively participating in it, some of at least discussing it or encouraging students to discussing it. And as in such movement or in this kind of parents that I, that I started seeing how the political language that I I studied translated into politics and then where civic skills broadly defined, including skills to have a conversation with others, intellectual or political conversations with others, but also skills to, for example, way political decisions act responsibly and to think about communities and, sorry, communities and responsibilities and membership in, in these kind of contested ways. Right? And so I guess starting from that moment I started, I, I started recognizing that the things that I learned and the things I have been grappling with can and should be considered as political by their own very nature. And that's, that's, I think that's when I started cultivating this practice that whenever I read a new text, I will be thinking about how to, how to make it relevant to yes, students, students, but students as potential or already political actors and citizens. And that's also what I think eventually got me to towards civic teaching and cyber civics initiative. Yeah.

- Yeah. So that's fascinating. So is it fair to say that your experience in a, in a lively and relatively free political context actually brought the texts alive for you in a way that

- Absolutely, they had

- Already been good at reading them and interested in them, but they, they, they, they became alive. So that's, that's something yeah, absolutely. Something there about what might bring texts alive for other students as well. So shady, you, and we'll come back to both of you, and there are questions, a lot of questions that are more substantive, but Shadi, you actually did study in some other countries, but I'm not sure that's, that's the path you wanna describe. Your path may be more intellectual or yeah, inside books as you, as you've navigated the, the world. But how have you come to this conversation about civic education in, in the us

- Thanks, Peter. So yes, I, I grew up not in the US but in many different countries in Asia and Europe. And I think as a result, deeply interested in, in the frameworks with which we're thinking, because we come to the question of what a civic education is so differently depending on what our background is in, in the west. And you know, through its heritage from the Italian republics and through the Italian republics back to Greco-Roman antiquity, there's been a tradition of, of civic education and, and civic training that has focused on things like responsibility, participation in juries and deliberation, the ability to engage in dialogue with others. The a a certain awareness of the nature of political rhetoric and the shapes it can take and how to push back against it. And a tradition that's always told to be skeptical of power and demagoguery. Again, those are the, the athenia, the Athenian genetic background in American civics education. But in other countries, what civics is, is not merely political. It seems to me to also have more to do with the self and with ethical self-regulation. And of course, if you look at the Chinese tradition, and I don't know mean the old Confucian examination system before the fall of the TIC system, but I mean, even today embedded in, you know, Marxist Leninist teaching and so forth, there's still this sense that what's really important in the citizen, which itself is a, a temporal category in China, it's not a 2,500 year old category as with the West or Greece. What's important for the citizen is self-regulation, ethical awareness, and a sense of one's role in society, which is also shaped by an understanding of one's role in the family and a view of the state as the family writ large, right? So that, whether it's the emperor or the head of the CCP, there's a, a sense that this is family and that harmony rather than questioning and self-control, rather than maybe dialogue, are the most important things. And so given those very different frameworks, I find myself very stuck about what is civic education and how should we be defining it? And yeah, those questions,

- Let's, that's opens up the question, some of the questions, the central questions here. So I'd love to hear Ian and Simon and after a little while, Jesse, also on these questions. But yeah, I mean, I I'll just say obviously the, the, the relationship between the public and the private between ethics and politics, these are contested questions in every tradition that I know. And so while there's a certain genetic thread from a certain Athenian democracy down to the present, also plenty of resources for thinking about things like self-regulation or the private, private sec sphere or the inner life in, in what we call the west. But so I'm, so you characterize it in the, as a contrast, but I'm just curious if that contrast works for everybody or anyway. Well, so I suppose to be a little sharp to two questions, does Shadys contrast work for everybody? And also is this a useful way, is that comparative approach a useful way to think about civic life? Like how should we live as people on this call? Is it useful to think about that by thinking about the two, two traditions in juxtaposition? So I don't know, Dohan, do you have thoughts? I see you nodding.

- I think I basically agree with Chad's characterization. So because I don't have any experience in, in American civics, I, I didn't grow up in this country, but I can say for sure that in China, kind of, there is a very strong tradition of emphasizing self cultivation, self-regulation. So I don't think kind of in China or maybe other Asian traditions, there would be a very sharp distinction between the political and the moral. So moral education and political education, they are intertwined. So the question is, the question is kind of to what extent a super submissive political environment would truly cultivate freedom, sorry, not freedom, but, but morality, because things kind of, the Aristotelian tradition, we know that actually the cultivation of morality requires certain degree and maybe a very substantive degree of freedom so that people can reflect upon those moral principles. And so that when you become a moral person, actually you would reflect upon that freely and you would even have the freedom to try different principles. And ultimately you may reach the conclusion that, okay, so I submit to those more principles out of my free view, not out of kind of some external imposition or suppression. So I think what Shadi described about the contrast between the, the west, if we use this very generic term and the east would hold, and what I would say more is actually kind of to what extent self cultivation would require freedom. And that would a little bit complicate the relation, the, the, the contrast between the east and west. So probably kind of in eastern civics, if it is a well-regulated Asian society with a Confucian legacy, probably kind of the assumption of freedom or maybe kind of the encouragement of freedom would still be extremely important.

- Thank you. Simon, where are you on this?

- I have, I have some mixed feelings about, about this topic. I will start with the idea that the, the, the sense that yes, when I, I mean the first thing that I have to note is that it's hard to like what we call civic education today, the counterpart in China has, like, they are thrown different things that you might count as other Chinese counterpart and they're not exactly the same. But my experience back then was that yeah, indeed private public definit, sorry, distinction was not heavily discussed, at least not in my experience. I could be wrong a little bit about what we, and, and, and yes, it, it's also true that moral and political leadership or moral on political cultivation, all all more often the same thing or you know, intertwined in Chinese example. But a little bit more about this topic or a little bit more about this question that I'm reflecting on specifically about what they both do, I think in the like different kinds of civic education both do, is that they serve to provide a certain kind of a set of political language and vocabularies to the citizens, whether you in a set in, in a certain way that that would enable them to discuss political fears and, and in the communicate communicable way. And I mean, I mean we might eventually get into this a little bit deeper, but my sense is that a lot of times we don't necessarily always agree with what's being taught the contents, right? Either you are in the United States or somewhere else, or China Chen just mentioned this, that a lot of, you know, Marxist professors in China had some freedom to discuss critical views about Chinese history, about ideology, et cetera, et cetera. That's absolutely true. What I find particularly intriguing is that even those kind of disagreements still enable the shared political language. In the Chinese case, there will be a certain kind of, you know, Marxist under understanding of history, economic base determines superstructure or a certain kind of stages understanding of history, those kind of vocabularies abs the means and, and political language would get reinforced, which I'm not saying is necessarily a good thing or bad thing, but I think that's indeed something that the civic education provides for the citizens.

- So actually let me build on that. So that's, that's a way of, of taking us into the next territory. So you could imagine that American students in on the whole are getting a certain kind of common vocabulary too. And some of the components of it included separation of between state and private sector and a, you know, a difference between politics and ethics and these kinds of questions. So then reading serious Chinese political thought would actually complicate some of those assumptions In some ways it, it might, you somebody might even say it, it would undermine a shared language which allows us to govern. 'cause it, now we have the other, other language. But I, I, I guess I wanna hear about the pros and cons. I'm imagining mostly the pros the advantages of in, of asking American students to do things like read, you know, they read the nalytics and translation, I mean, read serious Chinese thought, what, what would a chi, what would an American student get outta that? And are there any drawbacks to, to that for any, any of you shady maybe, maybe you haven't heard from you for a little bit.

- I was actually wondering, Peter, if this is not an answer to your question, I apologize. But whether this is a question for Americans, whether the two party system and the kind of political rhetoric we're seeing now makes civic education more difficult in the US than in China.

- Okay, well let that let question hang there. Or either are the other two panelists or, I mean, I, I don't think I know the answer to be primarily because I don't know enough about what's happening in China. Certainly polarization makes it more difficult in the US more difficult even to even literally to offer classes in, in a case of, of school because it's, it's so fraught. Indeed.

- Yeah. So as to the question of whether American college students should be reading Confucius, I think yes, but I think for them to be reading Confucius in a, in political science classes would be deeply confusing. Or even in civics classes would be deeply confusing because they wouldn't have, they wouldn't have confronted the notion that ethics and politics could be the same in some cultures yet. And so it would be a, a category confusion. So there would need to be further background before we just threw the analytics, I think at students.

- Sure. But Mel, maybe, but that would also be a reason to do it. In other words, it wouldn't just be the text, it would be the text plus an explanation, but the result might be beneficial.

- Fair enough.

- But I'm curious what, what, yeah, Don Shannon, do you have thought about this?

- Yes. So my view, and this is a very firm view, that Confucianism is definitely not outside of the western tradition because the Fanging fathers actually read the Confucius and the before, the Fanging fathers, the European enlightenment generation, and even before the 11th generation, they all read Confucius. And one could say that our theories of the modern state actually is partially built upon certain Confucian principles. For example, even kind of those Catholic and European ideas about natural law actually also kind of was partially enlightened by the Confucian ideas about heaven, about kind of so-called heavily principles, the mandate of heaven, those kind of things. So, and I have also seen some research demonstrating that even kind of during the movements of African American civil rights movements, so a lot of African Americans intellectual leaders actually use the Confucius ideas to advocate for the equality of opportunity and a certain degree of meritocracy. So I would say that study Confucius would contribute probably rather directly to American understanding of themselves, and especially when meritocracy as a political concept has been occupying the center stage of our political debate, learning something about Confucius and also the Confucian tradition and also the political and historical experience of China would be directly beneficial and especially a higher education when we talk about kind of credentialism. So in China there has been thousands of years practice of credential. So that's the reason why I feel that even though I don't think I am in the field of civics, I still think that kind of teaching Chinese history and ideas thoughts can contribute directly to American students understanding of their kind of situations.

- Great. I wanna hear from Simon too, but I kind of comment from me is, I mean one, and you didn't go this far Chen, but one view would be there is no such thing as, as west the West, it, it's, it's way too complic. There's way too much diversity plurality within, within whatever we would define as the West, and way too much interaction going all the way back to, to ancient times. So, so in some ways it's a, it just doesn't, it's not an analytically clear category to talk about the west. So for example, there have been plenty of people living in Europe who have thought that ethics was incredibly closely connected to politics or, or that the, that self have have believed in self fashioning or whatever, whether they got it from Confucius or came from different paths. So that, I mean that's a, I've just said that in a strong way in order to provoke reactions, but I actually sort of believe that that the, that the west is a misleading category, Simon. So I think the question on the table at the moment, and then we'll change check a little, is what are the advantages to an American student of studying serious Chinese thought?

- Excellent. And I might, if I may, am I, I might divert, divert a little bit from Confucius to talk about, you know, other kinds of political thought, political philosophy, mostly because I don't direct always directly teach Confucius. I teach more contemporary subjects and themes. And when I was at Stanford, I taught a course roughly three times the thing that's called political politics and political theory in contemporary China, which is by design half history and half political theory. And it is especially designed in this way because I think it is particularly useful for students to grapple with the political theoretical of philosophical concepts because they were proposed to be universal ideas and they give students an entry point to a context that, that they are vastly unfamiliar with. And they are, they're about to get confused a lot of the times, to be honest. And that confusion I took like the, the kind of confusing sentiments, I took them to be good sentiments for teaching actually, because it, it, it opens up a certain things that you are vastly unfamiliar with. So for example, most students are familiar with some versions of the concepts of democracy as they grew up in the United States. And now I present them speeches, documents, and academic writings or or archives to show that, you know, in forties and fifties, Chinese leaders, Chinese pol political actors were fully convinced that, that they were building some versions of democracy. And they were also able to convince some people, not all people, but some people, including many Chinese people and some western observers who were layer in China, alright? And they give students a puzzle. For example, if Chinese clams of democracy were, were worth dealing with in a certain way, right? Doesn't mean we have to accept their, but if they were worth dealing with and engaging with, what were the base of making such claims, what kind of democratic thought democratic theory do they claim to be pursuing? And based on what conditions did, did they develop this specific understanding of the democracy? And how was that different from let's say, American understandings of democracy in the 18 hundreds, 19 hundreds, 1950s or even now. Right? And this, in this sense, I think some versions of Chinese democratic thought not only give students an entry point to grapple with other context, but this also in this process that they obtain a chance to re reconceptualize themselves their education and their identity in, in a way that's more sophisticated. Yeah,

- You great. Just a couple of comments about how the conversations proceeding. One is that people are putting questions in the q and a box and I'm, I'm reading them and that's very welcome. As we, as we go forward, we'll start using those questions. And also, Jesse, I would love to bring you into the conversation. Would, would you first of all like to tell us just a bit about yourself and, and your kind of root into this, this webinar today, but also what, when you hear this kind of conversation from your perspective, what do you, what do you, what do you hear? I mean, what, what, what do you think of it?

- Sure, thanks Peter. So I'm an undergraduate at the University of Chicago, but I grew up in China. My experience is, I would say atypical for both just an American undergraduate and also for like a Chinese student. This was in part because I have had contact with several different educational systems within the Chinese context. So I started in a very traditional Chinese school. I had civics classes as part of my elementary school curriculum. Simon, and you guys will probably recognize this, but I wore the, the green ribbon that signified, you know, my standing as a student but also as a member of larger Chinese political society. After that, I moved into an American school in northern China. So this was like a fully American kind of experiment happening in this like rural area in China, which was also really interesting to see. And then finally I moved into what would be called an international education system. So this is a school that was run by Chinese administrators, borrowed heavily from the Chinese educational curriculum, but it was intended for it, it intended for its students to go abroad afterwards. And so in many ways, I wonder if that experience too is an example of how perhaps a more western conception of civics may be operationalized in a Chinese context. That could be interesting to think about. But yes, that is generally my background and yeah, did you have other parts of the question?

- Well, well you answered my question as I asked it, but I I did wonder when you do, so you do, among other things, anthropological research in, in China, right? As part of your, do you think of that as a civic, as a civic, something you're learning, learning to be a better participant in public life, either in the US or China by doing that?

- Yeah, I think so. We've spoken a lot about how the moral and political are often conflated in China. I wonder if it would be helpful for the audience to kind of gain a better understanding of how civics education works within the Chinese educational framework, which is that, you know, civics education is part of education. I think in the US the two can be separate, but this is a required class from when you start elementary school all the way up to college. So students are in classes where they will be reading texts and given exams where there are case studies and then they have to write about the values that are most important in those cases, how they would respond to different situations. And a lot of times these are Chinese cultural values, things like humility and self-sacrifice and hardworking, but they are also very, very political. You are, you are trying to, you know, do your best in order to advance like the political agenda. You are hardworking within this kind of political framework. And crucially, I, so the civics has also worked into your advancement as a student. So the green ribbon thing I was talking about earlier is like a mark of your accomplishment in civics as a student that you get in first grade you get this little green ribbon and then slowly you update to a red ribbon. And then there are more groups that you can join as you progress in your educational journey. And in within this system of progression, you're standing in academics as a student who gets good grades, is very deeply connected to your standing as a, a person who is educated within this Chinese system of civics who can communicate clearly using the language within these frameworks. And so the two are very deeply connected and my experience of coming to the US has been more about severing some of those moral values that I very much still retain from my upbringing in China, from their political opera optimizational kind of Im impact. 'cause clearly that isn't as relevant in, in my undergraduate experience in Chicago.

- I'm imagining, I know some of the people who joined us on the as in the audience, but I don't know everybody. But I imagine that people are having somewhat mixed feelings about the, the the vivid story you told is fantastic. It's very, it's very enlightening, but I imagine people are having different views about whether it's good or bad that the students are thinking so much about personal character, that it's being done in a structured way. The pedagogy also, the fact that the state is involved in, in requiring studies of the state is obviously from a certain kind of classical liberal perspective worrying. So I imagine people probably think about it differently,

- But Peter don't, don't states always seek to imprint the, their version of the ideal citizen upon who are studying civic virtue, no matter what state it is. We also, us also has its version of the ideal citizen that it imparts in civics, right?

- Sure. But probably with a lot more caution and self-conscious and worrying about it and, and backing off it and you know, and then actually literally dropping the subject periodically and putting it back in and that kind of thing. I don't know, Jesse, you were gonna say one more thing on this? I think

- I actually have a question related to what Shadi just said, which is the Chinese civics is built into the Chinese system because it serves a very clear purpose for the Chinese states. You people are very well versed in these discourses related to civics in the context that they would like it to be. And it encourages obedience and respect for authority and rules. Does the US have a similar incentive to, to be doing, to be encouraging civic education in its more liberal western form, which is, you know, asking questions, political participation, raising dissent, are those things, do they have an incentive to pursue those things in the education system?

- Right, right. I I'm taking that as a little bit of a rhetorical question because instead of one that we just said, but, but it, it haunts, it haunts us because the, it's, it's not clear who really has a reason to invest in the civic education of young people. If that civic education is mostly about, about strengthening democracy, we have a for anybody, for all of you, we have a, a series of questions from Richard McGrail, which I also have been thinking about a lot myself, which have to do with the role of reading in civic education, particularly reading hard hard texts. I think because so all of the, all of all four of you actually, especially the professors here, are professionally interested in hard techs. That's what you do. And the alliance civics in the academy talks about grounding civic education in texts. That's one of the principles in the common statement of principles. But techs are under a lot of assault. There's AI summarizing them, there's resistance to reading and from different directions there's evidence that reading is just simply declining. And Richard McGrail says that the analytics was in the Stanford requirement curriculum and got pulled out because students found it in part because students found it difficult. So this is a question that is partly about the relation to China, but it's also just more generally about the humanities. What are you all finding about teaching with texts and especially with hard texts, especially with texts that come maybe from a different cultural context, but that's also true of, of Aristotle. It's not just true of Confucius.

- I'd be happy to say a few words.

- Yeah, you're a good person for that. 'cause I think a lot of your life has been about that.

- My life. Yes, indeed.

- Yeah, no,

- One of the questions was whether Plato and Aristotle and other of the Greek political theorists didn't themselves combine ethics and politics at the start of the Western tradition. And the answer is yes. And this goes to the question about texts, because texts can be good to think with and they can also be appropriated. Well, they're always appropriated and used. And what they teach us to do is to take a, a complicated set of facts in a book and create arguments about them that lean upon those facts and utilize them to create a irrational purposive statement. So arguing about a text, especially texts like Plato or Aristotle that have been, that are currently being found good to think with by the Chinese and have also been found good to think with by Westerners for millennia. Those talking about those texts help us model logical disagreement because the words of the text are there in print in front of us. And they're not debatable, they're not up for grabs in the way that somebody spouting facts that other people don't have access to. Might be they're not up for grabs in the same way that personal experience is. They challenge you to create an argument and support it using something that's accessible and available to everybody who has that text. And why close reading is so important because it models these habits of argument and reason that are so important to civic education. And so the fact that the alliance for civics in the academy is really stressing the reading of texts as part of what makes, helps to make a, a good citizen, I think is, is spot on. And I, that's also an endorsement of course for the humanities that are currently under siege.

- Love to hear from others on this. And actually, you might also just think of a different, an additional question as you're, as you're answering, which is who, who's, who's qualified to teach these kinds of texts? I mean, you know, I I have very, very limited, I have no Chinese at all and very, very limited really contextual information should I be teaching the analytics? So, so, so one que so the first question was what do we get out of teaching civics through difficult texts? But the second question is who who's qualified and what do you need to have to know in order to teach these texts? So I don't know, do you have thoughts on these?

- Yes. So I would want to kind of raise a relatively provocative point. So I would say that in the age of AI probably is a good time to revive the very old fashioned great book style liberal arts education because, so right now I think the popular way of organizing our syllabi is we just a kind of peak and choose different readings from different traditions. And we have some texts from Confucius, we have some texts from Aristo, we have some texts from hos and some texts from John Stewart Mill. So students would be able to kind of have a very general view about different ideas about political thought in history, not only of the West, but also of the East. But so right now with AI, as we have discussed, so students they say, okay, we hate reading, or maybe we can just kind of outsource our reading to ai. They can summarize for us. So that reminds me that when I was in China, actually that was definitely before AI time, but most of the classes actually teachers would not assign readings the instructors, they would just lecture in front of 200 students and you're not required to read any primary texts. So what you need to do in order to pass the final exam is actually to, you know, a lot of classes to memorize the PowerPoints provided by the, by the instructor. So basically kind of, I didn't find those classes very helpful. So what the few classes that I, that I found extremely helpful was offered by philosophy department. So one class for the entire semester, we just read Nicom Ethics and, and Niches, genealogy of Morals, a different class. We just read Plato's Republic for an entire semester and a third class that we read Hobbs, Leviathan and Russo's Second Discourse. So I suppose right now kind of, it's a really good time to revive those kind of practices so that we can guide students over an entire semester just to focus on one grade book that is, that provides kind of a funding role for our democratic society. So why not we con we constantly complain that students cannot read a book, a single book cover to cover. So why not we just, the guy students read Democracy in America for an entire semester so that they can know that kind of what is the best mind, what the best mind in history have said about American democracy. So this in this way actually I would say students would appreciate. So we just, the kind of, we would revise our pedagogy of asking students, expecting students to do the reading before each meeting. We would actually kind of give them some kind of encouragement so that they can do some reading. But the most kind of discussions and the text-based discussions would happen in the classroom that we put some important texts on the slide and ask the students to have some reflections. And this is exactly my approach of teaching the analog, analog is very hard to teach and form a a lot of American students, they just don't, don't, don't believe Confucianism is just confusing. So, but kind of guiding students read each passage line by line is a very good way to ask to help students understand texts.

- And then there's a question about whether understanding texts is a good way to make you a better citizen or a better person. I think, I think there prob it probably is, but that requires a separate argument 'cause it's not, it's not immediately evident. Simon, how about you? What are you thinking about texts and importance? Yeah,

- No, sorry. Thank you so much Peter. And if I may, I will lean towards your, the, the the second question that you also raised Yeah. Is qualified to teach what?

- Right. Thank you. Yeah.

- That may be intentionally provocative for a quick moment I'll say no one is qualified to teach anything, but let me explain.

- That's a good answer. Yep.

- Yeah, I mean, of course we have experts, like we are all experts on over certain things more rather than others, right? We are professors what ch to do and what our research focus on certain things. However, to be an expert of something is different from the capacity of teaching something actually, they might sometimes be related in my mind, of course they are a lot of times related, but they are not exactly the same. And I have seen in my myself, experts, like people who I'm sure are experts, something teaching in terrible ways. I've seen those classrooms. I've, I believe we've all seen those classrooms. But I do think that the, the, the idea that, or having the sense that no one is fully qualified to teach any material, even if those are materials that they are most comfortable with as a philosophical principle, let's say, right? Give us a certain kind of way of thinking about, you know, whether I should teach the this specific thing or not. I do that, like I do this all the time. In fact, I think designing is new syllabus is one of the few moments that I would actually actively push my myself to engage with materials that I've not encountered before. Especially you can do it in a, in a reasonable dose every time, right? Like this new semester, you can add a new section on third things and then you can explore how, how you can, how to incorporate that new section in your existing syllabus. And that I think, I mean like even when I'm less familiar with certain materials, for example, in the past, past the last course I taught at Stanford, I tried to incorporate a lot of Arabic political thought into a course about the, about the Cold War. I found it useful. And I think particularly the, the thing that was particularly useful was how I explained my, my struggles Yeah. Of interpreting these texts to my students and, and worked with them with their struggles. And the, the unfamiliarity, the confusions I think were important moments. And not just the students' struggles, but also the teacher's struggles. They can also be useful in a civic classroom.

- Yeah. Thank you. And by the way, Josh Ober in a comment that everybody can probably read notes that both Josh and Simon had stellar student evaluations and Jo, which, so we need to record that. And Josh asks whether we can bring in this kind of teaching into lower level courses with less fully prepared professors or less specialized professors. And Shati wanted, did you want to answer that live looks like you did?

- No, I was actually reading the question and wondering about it. Oh, okay. I, I I don't know. I mean, what matters is how much time does one have to spend with a text? What background is one coming in with what is one hope for students to take away? It's, so it's a complicated question.

- Okay. That no problem. That's, that's fine. I think we should address a, a different topic before we close. Also, I'll Oh, and, and, and that's a good point. So before we get there, Don is saying, let's ask Jesse that question. I agree. That's a good point. So Jesse, the question is about levels, about, about sort of where, where in the, where in the undergraduate curriculum. So do you think it's appropriate to study, you know, the analytics or something like that kind of early in every and more, perhaps more importantly that everybody should study it as opposed to it being a specialized thing for students who are, you know,

- Sure. Undergrad is only four years. It's actually not that long. And I think you, the reality is you will be losing a lot of students in time if it is only taught in later years. Now. There's definitely an argument to be made about how much they can engage with those ideas, maybe earlier on in their educational journey. At least from my perspective, I don't think a first year is necessarily that much worse off than a fourth year college student. But yes, so generally I, I do believe that these texts should be taught for me, maybe in part because of what I see as a really important like civics education value, but also education value generally that perhaps isn't emphasized enough, which is curiosity. This is the greatest advantage for me of reading a text instead of asked to memorize PowerPoints through my education. I want to become more curious about the world around me, not just learn more and absorb more information. And this to me does not seem limited to like a fourth year, third year college context or even higher education at all. I, I think if someone who doesn't graduate from high school or from middle school can walk away from their educational system with a desire to continue learning about the world around them in whatever form that takes that is just as valuable as learning what it means to be a citizen or how to participate or, you know, knowledge of Confucianism.

- Thank you. Great. So we have about seven minutes left and, and the last two minutes I need to make some announcements about how to join the other webinars. So I think, so in about five minutes I'd like to raise the que big question, which is I've, in my mind been lurking there, but we haven't really addressed it directly, which is China, people's republic of China would generally be classified as authoritarian United States would generally defined as demo democratic. Although, for example, CIVICUS just downgraded us this last week to less than fully democratic. But so, so there's a serious argument that we're backsliding or not fully democratic. So, but the question is, what are the advantages of, for an American student of studying thought coming from a explicitly authoritarian context or, or encountering thinkers such as, such as yourselves coming from an authoritarian context. Do you, I think, I think this is mainly for Hun and Simon. So maybe if you each want to take it and then we'll close out.

- I would also love to contribute a thought if I might on that.

- Yeah, why don't you just, just I'll make you make it quick, but go for it.

- Yeah. It'll be very quick. You bet. So when I became interested in China 20 years ago and spent some time there, it was a huge shock for me to understand that there was a philosophical tradition that did not emphasize logical deduction as the premier principle of what philosophy was as it has to this Play-Doh and Aristotle, well I'm exaggerating slightly, but you know, the deduction, I think therefore I am, et cetera. But instead emphasize qualities like then humaneness. And I thought, oh my gosh, philosophy doesn't have to be about deduction or ideal forms, it can be about humanness. And that was a revelation for me. And it had nothing to do with autocratic or not autocratic,

- Something else to learn. Thank you, Simon.

- Yes. The quick way to to to, to say this is that I use Chinese philosophy to teach self understandings. I teach, I use philosophy to reflect on, you know, not necessarily entire community, but certain important secs of the Chinese community, like citizens, community, how they understand their work role in the world, their word role in society, their understanding of what the future China will be or a future world would be. And author like. There is no denying that China is authoritarian, but we also probably would recognize the authoritarianism or an authoritarian country as not something that of course the Chinese government or the Chinese citizens actively embrace as their identity. Sure. Just the party will still insist that we're doing democracy and the citizens might have different understandings of what they are actually doing or committed to. And I use philosophy to reflect on these things and I think these are valuable things for American citizens to learn.

- Thank you. Perfect. This may be the la your last comment actually, everybody's last comment.

- Definitely. Yeah. Yes. So every time that I begin my classes on Chinese political side or Chinese politics, I would just give students a warning that, so I know that politics right now is highly polarized in the United States, and we are talking about China. Originally I thought that, okay, people may be kind of just curious about China because they don't know too much. So maybe kind of, I would have a relatively easy time to just introduce a, a, a, a country to students. But it turns out that was not the case because students, they would project their ideas about American politics into their conceptions of Chinese politics. That's everywhere. And that's kind of every time that I teach those classes. So I would tell students that the Confucius tells about kind of the golden rule is to hold the mean that is kind of to be on the middle. So we would avoid one extreme that is to demonize China to say that, okay, China is an authoritarian system. Every Chinese citizen is just a super submissive. There is no agency, there is no thinking. So the other extreme is to say that, okay, China right now is doing so well, it's so stable, so prosperous, and is actually a shining example of the future of the world. So both extremes can be harmful and those extremes can map on the political polarized, the political spectrum in the United States. So I think that giving students some ideas about the internal power, logic of Chinese politics can be beneficial for students. For students who think China positively, that would provide some caution. Who for students who think China very negatively, that can also give them some ideas that the United States and China are not radically different. So I remember Simon actually raised a very important point earlier in our discussion. When you project, when we ask the students to project themselves into a concrete political system, actually they would have a better idea about how to react to those different political situations. And after this kind of process, I would say that students would come up with a better understanding of politics and better understanding of how to be a citizen, not necessarily kind of a good citizen in different political processes. And it's, the opportunity for it is actually kind of the, the duty. And I would say the, the, the instructors should not teach students any ideas about China. I'm a Chinese citizen, I'm patriotic, but not patriotic to the regime. I'm patriotic in my culture. But I think as a good teacher, I should just kind of hold my personal ideas and ask the students to judge and whatever judgment they will make, I would just say, okay, that's acceptable after kind of going through all those different opinions about, about Chinese politics.

- Beautiful. Thank you. That's a very nice way to end. So I'm gonna turn to thank you all in a minute, but I wanna say for those listening or either alive or or later, 'cause this will be archives, you can join the alliance specifics in the academy. You can also nominate colleagues and so we'll, we'll have links. I think the, a link will go up in a minute or I can put it up. But for in any case, you can, you can search for the alliance specifics in the academy and see a registration link. So people are welcome to join and invited to join. People are welcome and invited to submit resources, commentary, and research. We have an ideas page with a lot of resources people are welcome to, to submit things that they want others to read. And the next webinar is January 14th at 9:00 AM Pacific, which is noon eastern, it's called from Harvard to Hometown u What colleges can teach each other about civics. And it's really focusing on the big disparities in resources and opportunities depending on different kinds of colleges in the United States and ways that we can learn from each other. And that's, that continues a conversation that's been happening within the alliance specifics in the academy. Well, I think the best thing to do is for people to, to search alliance specifics in the academy, Stanford, and, and those, those links are there. And so the last thing I wanna do as we close out on time is just to thank a really great panel. Thank you. I, I don't, as I said, I really don't know anything about China, but I learned a lot from you and also just appreciate your thoughtfulness and collegiality and, and commitment to this call. And so thank you and see everybody at subsequent webinars in this series. Bye for now.

Panelists:

Dongxian Jiang: Assistant Professor of Chinese Studies, Department of Languages and Cultures, Fordham University.

Shadi Bartsch: Helen A Regenstein Professor of Classics; Director Emerita, Institute on the Formation of Knowledge, University of Chicago

Simon Sihang Luo: Nanyang Assistant Professor, Public Policy and Global Affairs Programme, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

Moderator:

Peter Levine: Lincoln Filene Professor of Citizenship & Public Service, Tufts University; Executive Committee Members, Alliance for Civics in the Academy