- History

- US

- Revitalizing History

When high school students are first taught the history of the American Civil War, they often are told that the Battle of Gettysburg and the North’s capture of Vicksburg, both occurring during the first week of July 1863, marked the turning point of the war. While from a strictly military vantage point this may be true, such claims mask the political peril that Lincoln endured well into the summer of 1864, when demands in the North for an immediate end to the war nearly caused the president to offer generous terms to the South that would have allowed them to keep their slaves in exchange for a cessation of hostilities and the restoration of the Union. From a strategic and political perspective, I contend that it was actually General Sherman’s capture of Atlanta during the first week of September 1864, that finally gave the North a decisive advantage that they would enjoy for the remainder of the war. Taking this key Southern city electrified the North, shoring up resolve to stay the course under Lincoln’s leadership, and ensuring his re-election that November. That bought the time necessary for the commander-in-chief’s new strategy of attrition to succeed.

In some ways, Lincoln’s change in strategy in 1864 was a nod to the effectiveness of Confederate general officers who were able to fend off the North’s attempt to end the war quickly with decisive battle. Still, we must also credit Lincoln’s remarkable inner-strength and wise decision-making skills because when faced with those early failures, Lincoln did not remain stubbornly entrenched in his formerly held positions. Instead, he assessed the relative strengths and weaknesses of both sides of the conflict and changed course to exploit the significant resource advantages the North enjoyed over the South.

As early as 1862, while still searching for a decisive blow in major battle with Confederate forces, there were signs of this impending change when Lincoln took action to limit the South’s ability to sustain a long war. Endeavoring to cripple their war effort, after the Battle of Antietam, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing the slaves in the Southern states still in rebellion as of January 1, 1863. That same year, Lincoln ordered stepped up efforts to strangle the Confederacy from external support, further tightening the blockade of Southern ports. These actions set the stage for the eventual strategic pivot in 1864.

Then, in March 1864, Lincoln made major changes to the high command of the Union Army, empowering the kinds of leaders he thought would best implement the new strategy. This included Generals Grant in the east and Sherman in the west, and he gave them guidance to gain contact with Confederate armies and not let go in order to wear them down. And, if Richmond proved too elusive of a target for the moment, Lincoln wanted Atlanta taken soonest.

These Union generals quickly complied. In the west, Sherman took Atlanta later that summer. In the east, Grant implemented this new guidance with vigor, beginning in May 1864, when after Union and Confederate forces essentially fought to a draw at the Battle of the Wilderness, to the surprise of even his own troops, Grant ordered his men to turn south and to stay in contact with the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. Up until that point in the war, Union forces generally would disengage after major battle in an effort to regroup with the hope of picking a new place for epic battle where the complete destruction of the Army of Northern Virginia could be achieved. After the Battle of the Wilderness, Grant’s decision to go south and stay engaged marked a new phase of the war. One that would significantly increase casualties on both sides going forward, but of course, for the North that was now the point.

Meanwhile, back in the west later that fall, after consolidating his gains in Atlanta, Sherman prepared to march towards Savannah with the intent of destroying everything in his path along the way. Southern forces, now under the command of General John B. Hood, sensing the Union change in strategy and desire to stay in contact, made a risky decision to head north towards Chattanooga and Nashville hoping that this would cause Sherman to follow him. Sherman, seeing firsthand the demoralizing effect on Southern morale that Union forces had achieved by occupying and systematically destroying a key cultural center for their way of life, concluded he could best achieve Lincoln’s intent by doing the same to Savannah. So, Sherman did not chase Hood and instead proceeded towards Savannah, confident that Lincoln still had General George Henry Thomas with a sizable army in Tennessee to deal with Hood.

Looking backwards, it’s tempting to underappreciate the boldness of these decisions by Generals Sherman and Grant, but they were risky and decidedly different than earlier ones made by their more risk-averse predecessors. Importantly, these moves were nested with Lincoln’s intent and new strategic approach to winning the war. While one general kept contact with the Confederate Army and one did not, they both headed deeper into the heart of the Confederacy, psychologically dominating their foe and destroying their will to fight.

Consequently, by the end of 1864, the fate of the war appeared all but decided. In December, Confederate forces in the West under Hood were making a last desperate effort to capture Nashville, but as Sherman anticipated, Union forces under General Thomas smashed them, essentially rendering that Confederate Army non-combat effective for the rest of the war. Meanwhile, Grant’s pressure on Lee was unrelenting. Even as casualties horrifically mounted on both sides, Lee had no ability to reconstitute losses. While this was happening, Sherman resolutely marched with impunity towards Savannah, capturing it just before Christmas, delivering yet another decisive blow to Southern morale. Thereafter, Sherman made no secret that he planned to move on Columbia, South Carolina next as he continued the ravaging of the Carolinas, with the ultimate goal of linking up with Grant in the spring to help encircle Lee’s forces somewhere in Virginia.

Meanwhile, to support ground operations, Lincoln continued to synchronize naval operations and diplomatic activities. While Lincoln’s war-long effort to keep Europe out of the conflict was proving successful, it was never a forgone conclusion. In fact, for a time in late 1861, it appeared that war with Great Britain was possible, a crisis brought on by the “Trent Affair.” This developed when Union forces boarded and seized for a short period of time the British vessel RMS Trent. This British ship was transporting to Europe two Confederate diplomats who were seeking England and France’s recognition of the Confederacy. Union forces took these Confederates as prisoners and then let the ship sail on to England, but the British Crown and Parliament were furious with this brazen action by America.

Lincoln found himself is a very difficult situation, not wanting war with Great Britain but also not wanting to appear weak in more nationalistic domestic political circles. Lincoln was able to deftly deescalate the situation, however, peacefully resolving the matter in early 1862, without apologizing as the English had demanded. With both Great Britain reaffirming its neutrality and Union nationalist political forces placated that the country’s honor was not compromised in the process, Lincoln gave clearer guidance to Union naval forces going forward, hoping to steer clear of these traps for the remainder of the war. It was never lost on Lincoln that France’s entry into the war during our own Revolution over four score years earlier proved decisive to our victory. Europe, Lincoln concluded, must remain neutral for the North to prevail.

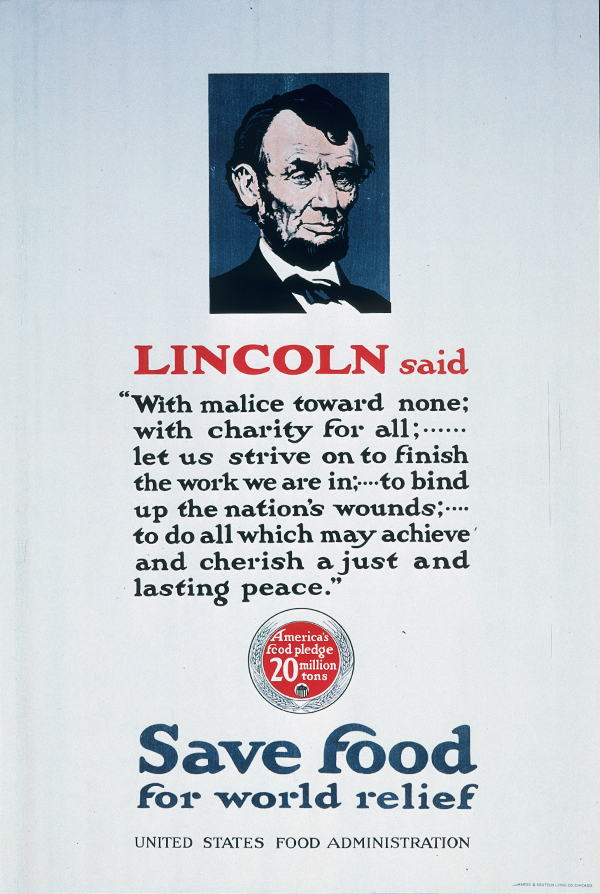

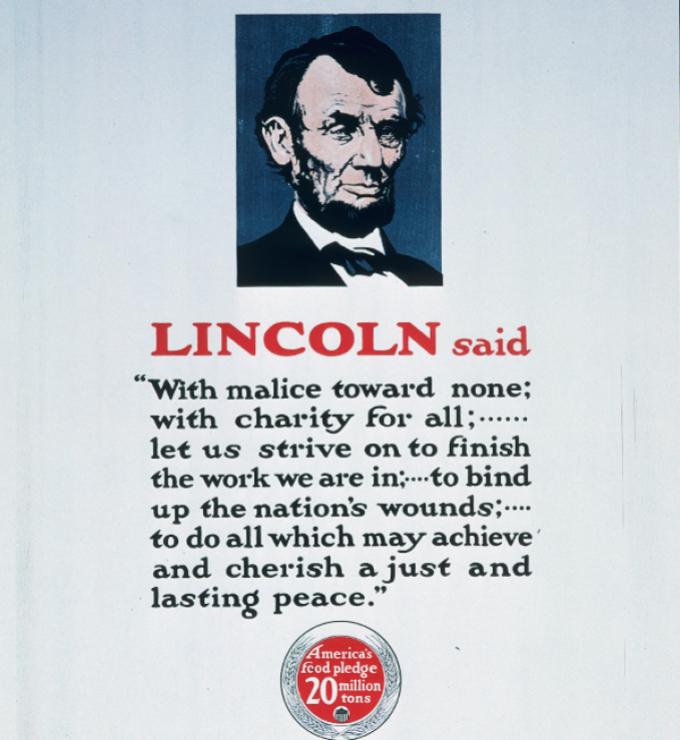

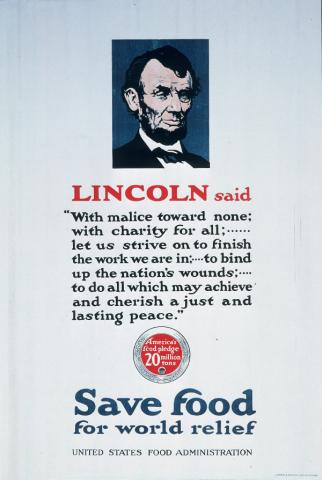

Lincoln’s embrace of a “malice towards none and charity for all” approach with the South also enhanced his diplomatic efforts. It not only gave European diplomats an effective talking point when they engaged with Southern leaders, assuring them they would not be summarily executed and their lands confiscated and razed Carthage-style (…the South knew Europe was interested in Southern commerce); it also gave credence to realists in the South that surrender could be honorable if a military victory could not be won. Lincoln was betting that General Lee would be among those open to such an approach.[1]

It’s easy now to look back and declare all of this was destined to happen, but that belies the master stroke Lincoln accomplished with how he ended the war. In the spring of 1865, there were no guarantees of anything. While the strategy of attrition was brutal for both sides, realists throughout the country understood Lincoln chose this path only when it was clear that it was the one path that could produce the kind of victory he articulated from the start. Advancing this strategy with a clear message of “malice towards none and charity for all” created the space for potential honorable action from soon-to-be former Confederates who always reserved the right to “fight to the last man,” including full blown guerrilla warfare and insurgency against reconstruction efforts. While eventually, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) did foment an insurgency, imagine how much more formidable it would have been if Confederate forces transitioned from conventional to unconventional warfare before Appomattox; and had that insurgency been led by General Lee and Jefferson Davis instead of Nathan Bedford Forrest?

Lincoln’s wise decision-making in the last months of the war enabled our country to take the first steps down the long road of peace on a solid and conciliatory footing. His careful, determined, and steady decision-making throughout the war, and especially his approach to conflict termination, should be studied by historians and statesmen who seek to learn how to win the peace. Indeed, had the Allied leaders committed to such a study and action in 1918, world history might have been decidedly different. Fortunately for us and the world, Allied leaders did better after World War II.

Going forward, let’s not forget these crucial leadership lessons given to us by President Lincoln.

Chris Gibson is a decorated Army combat veteran, a former Member of Congress, and a Participant of Hoover’s Working Group on the Role of Military History in Contemporary Conflict. This essay was drawn from Gibson’s latest book, The Spirit of Philadelphia: A Call to Recover the Founding Principles, published by Routledge in 2025.

[1] While General Lee did, in fact, surrender at Appomattox rather than wage an insurgency, his family’s land in Arlington had already been confiscated in 1864 for failure to pay property taxes and was turned into Arlington Cemetery. The U.S. Supreme Court later found in 1882 that this seizure lacked due process, and the United States paid the Lee family $150,000 in 1883 to close out the matter.