- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

- Health Care

- Economics

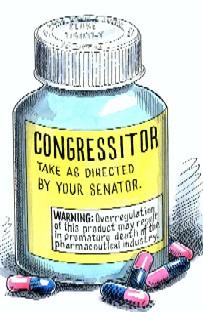

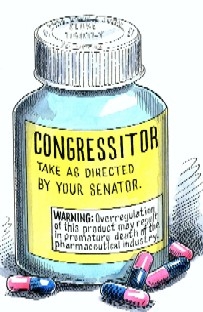

The winds of political fortune have brought the Democrats into power in both houses of Congress, and high on their 2007 agenda is tightening the regulatory screws on the pharmaceutical industry. It seems highly likely that the new Congress will seek to intervene on such hot-button issues as FDA oversight of drug safety, patent protection, and drug pricing.

The implicit premise behind this looming regulatory offensive is that Big Pharma (an epithet) is a 900-pound gorilla in need of domestication. In recent years, notable authors such as Arnold Relman, Marcia Angell, and Jerome Kassirer—all former editors in chief of the New England Journal of Medicine—have penned searing indictments of the industry.

These and other critics treat the industry’s multibillion-dollar profits as a sure sign of its permanent robust economic status. But those numbers conceal deep vulnerabilities. It is no accident that the shares of major pharmaceutical houses have been hammered over the past few years, even as profits appear to be at record highs. Wall Street values companies not only on current earnings but also on long-term prospects, which are cloudy at best for research pharmaceutical firms. Pfizer, for example, recently announced plans to cut one-fifth of its U.S. sales force, with a promise of further restructuring.

We shouldn’t be surprised. The huge profits of major drug firms are often tied to one or two drugs, such as Pfizer’s Lipitor or Viagra—profits that evaporate when their patents expire and generics enter the marketplace. The Standard & Poor’s review of pharmaceuticals thus starts somberly, noting that products with $21 billion in U.S. drug sales are going off patent in 2006, with an additional $24 billion to follow over the next three years—a sharp dent for an industry that today generates about $250 billion in revenue. All the while, the pharmaceutical houses also must absorb the legal and business risks needed to identify, patent, test, license, and market any new drug.

| It is stark evidence of how dire the situation is for pharmaceutical companies that the FDA, typically no friend of theirs on safety issues, has now actively intervened on their side in personal-injury suits that attack the adequacy of FDA-approved warnings. |

These trends should worry us all. Pharmaceuticals are not tobacco. There is no reason to rejoice in putting Pharma on the ropes if its business reversals hurt the very consumers it is trying to serve. The medical advances of the past 30 years are not just a matter of dumb luck. They are heavily dependent on patent law, pricing freedom, and marketing strategies that have allowed these firms to bring a wide variety of vital products to market.

The champions of further regulation argue that their efforts won’t limit innovations or curtail the widespread use of new drugs. But there are no free fixes. Too often ill-designed regulation gives us the worst of both worlds—slower innovation and more limited drug use.

We have much to fear in any new round of regulation. Bringing a new drug to market is already an arduous task. The FDA has consistently upped the number and type of clinical trials for companies seeking approval of new drugs; today as many as 60 separate trials are often required. Fewer drugs make it through these hurdles, and those that survive the ordeal cost ever more to bring to market.

Firms are thus caught in a vise. They have to spend more to reach the market, yet once there they have a shorter period of patent exclusivity in which to recover their extensive front-end costs. (One consequence is that it has become ever harder to persuade companies to invest in drugs that attack diseases or conditions that afflict small populations—thus exposing companies to the charge that they heartlessly put profits before patient health.)

| Pharmaceuticals are not tobacco. There is no reason to rejoice in putting Pharma on the ropes if doing so hurts the very consumers it serves. |

The risks of marketing a new drug have been further compounded as the FDA has become more willing to remove drugs from markets at the first sign of any real or imagined dangerous side effects. But although such FDA actions often lead to accusations that drug companies have not come clean about a product’s risks, it is usually the FDA that has made the incorrect risk calculation.

Last year, for example, early clinical trials showed great promise for a cancer drug called Iressa, which was used with success by many patients. After the early successes were not replicated in further clinical studies, the FDA adopted a Solomon-like solution: It allowed current users to continue receiving the drug but otherwise took it off the market. The FDA rationale was that a new drug, Tarceva, worked better. Yet it could never explain why patients for whom all other therapies had failed should prefer one last-ditch option to two. What is needed is good information about Iressa’s successes and failures. If that is supplied, surely oncologists can do a better job calculating the odds than the FDA, which has to deal with averages, not individual cases.

With other established drugs, like the antidepressants Zoloft and Prozac, the FDA leaves them on the market but requires they be sold with severe “black box” warnings that overstate the risks (in the case of Zoloft and Prozac, of suicide). Fearful physicians thus shy away from prescribing such drugs—not because of the dangers the drugs pose, but because they fear the warnings expose them to greater risk of medical malpractice suits.

Pharmaceutical companies, meanwhile, have their own lawsuits to worry about. The liability risks of mass-marketed drugs have increased significantly in recent years. Consumer-fraud class actions, now common, arise after drugs have been withdrawn for some adverse side effect. Nonetheless, litigants are often allowed to sue for refunds not only for unused drugs but also for the drugs that were successfully used, on the grounds that if the truth about the side effects had not been concealed (itself a debatable proposition), the pills would never have been purchased in the first place. The resulting loss in revenue leaves drug companies with even fewer resources to cover the thousands of suits for compensatory and punitive damages for drug-related injuries, like the multiple suits brought against Merck for its drug Vioxx.

Personal injury claims are immensely expensive to defend individually and their outcomes are fraught with error. Often they are propelled by inflammatory trial techniques that obscure the scientific evidence, which lay juries find hard to assess in the first place. It is stark evidence of how dire the situation is for pharmaceutical companies that the FDA, typically no friend of the drug companies on safety issues, has now actively intervened on their side in personal injury suits that attack the adequacy of FDA-approved warnings.

The common judicial refrain in tort litigation has long been that FDA oversight, no matter how comprehensive, supplies only a “minimum” set of warnings. In reality, however, excessive warning is the greater peril. The FDA faces fierce criticism from Congress, the medical profession, and the popular press whenever any approved drug exhibits adverse side effects. Yet these watchdogs offer little or no outcry when the FDA keeps a new drug off the market. Visible injuries are easier to track than lost opportunities for cure.

Perhaps the biggest threat on the horizon for the drug industry is mounting pressure to submit to price controls. One possibility is that the government will set uniform prices for all drugs. Another is that it would require a company to sell to all customers at the lowest price charged to any customer within the past year. But no matter how such controls are calculated, they could devastate the business. What’s more, they’re just not necessary.

Traditionally, patent holders could decide how much to charge for their wares. Public protection against excessive profits for drug companies came from three sources. First, the patent period is limited to 20 years, with about half that time used to shepherd a new drug through the FDA approval process. Once the patent expires, the entry of low-cost generics sharply reduces the cost of proven drugs. Second, the rapid pace of invention means that consumers frequently can choose between two or more patented drugs in the same class (Lipitor, Crestor, and Zocor, for example, are three statins used to lower cholesterol), effectively blunting the monopoly power of all patent holders. Third, antitrust laws make it illegal for any makers of the same or similar drugs to conspire to raise prices or reduce output.

Within these constraints, of course, the research pharmaceutical firms still must recover their huge front-end costs, which can run more than $1 billion for a new drug, over an ever shorter useful patent life. In addition, their successful drugs must generate additional revenues to cover the predictable flops. Yet companies need to charge someone for the initial costs of production, not just for the small cost of producing additional pills.

| Public watchdogs offer little or no outcry when the FDA keeps a new drug off the market. Visible injuries are easier to track than lost opportunities for cures. |

One common argument for price controls is that drug companies should spend money only for research, not for lavish marketing. Yet that shortsighted argument assumes that pharmaceutical companies could sell the same quantities of drugs without advertising them. Of course, the cost of marketing raises the total cost of production, but by expanding the consumer base, it lowers the average costs consumers pay per unit. Any system of direct price controls would thus play havoc with both research and marketing, drying up the capital needed for innovation.

The overall picture today shows a research drug industry under constant pressure from all sides. Industry critics greatly fear letting bad drugs on the market and simultaneously underestimate the real costs (in the form of forgone health benefits) of keeping good drugs off the market. In reality any sound risk assessment, whether by regulation or litigation, should take into account both kinds of error.

Critics also naively assume that investors and firms will continue to make huge investments in new products without any assurance of recouping their costs in the marketplace. But the drug business is too vast and complex to depend on individual altruism or government bureaucrats to fuel medical advances. As Adam Smith recognized long ago, the profit motive is the only constant and reliable spur to making the major investments on which the prosperity (and health) of any nation depends. Today’s pharmaceutical industry is not exempt from that enduring insight.