- Economics

- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- Energy & Environment

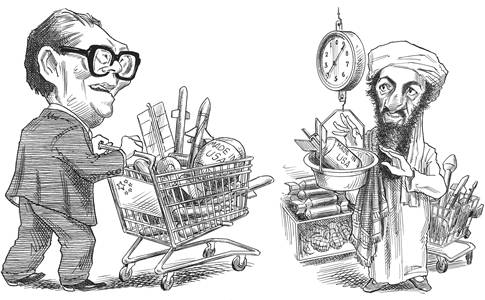

If you believed certain politicians, American companies would sell out their country if left to their own devices. These politicians are concerned about technology exports and how the government should control them. Unless we have better controls, they claim, hostile governments and radical terrorists could develop better weapons and threaten the United States.

No one likes the idea of Osama bin Laden packing a nuke, but, unfortunately, U.S. policy on technology controls is going way off course. In fact, our current controls have achieved a rare trifecta in regulatory nonsense: they hurt the American economy, violate basic principles of the rule of law, and usually do not improve U.S. security.

The main target in this controversy has been the U.S. aerospace industry (although computer and software manufacturers have also taken some hits). Critics complain that U.S. satellite and rocket builders are "rope sellers" (Lenin’s phrase describing bourgeois merchants who want so badly to make a buck that they would sell the hangman the noose for their own execution).

The recent controversies started when U.S. officials discovered China was making major improvements in the accuracy of its long-range missiles. Some of the Chinese gains seemed to come from espionage and some seemed to be homegrown. But some seemed to come from U.S. aerospace companies.

Satellite manufacturers such as Loral, Hughes, and Lockheed Martin had all used the Long March launch vehicle, manufactured by China’s Great Wall Industries. Integrating a satellite to a launch vehicle requires engineers from both sides to provide information about electrical connections, mass properties, operating rules, and so on. Also, the Long March had experienced several launch failures in the early 1990s. Insurance companies wanted Great Wall to carry out a detailed review to find out why. The American satellite companies that wanted to use the Long March agreed to help in the review.

|

This country’s draconian export control laws hurt the American economy, violate basic principles of the rule of law, and usually do not improve U.S. security. |

The U.S. companies made no effort to hide their assistance because they did not believe they were doing anything wrong. But when U.S. officials found out, they claimed that American engineers had revealed sensitive technologies to their Chinese counterparts—either in planning their launch operations or in the review of the Long March.

A close look at the evidence suggests that the technologies U.S. companies supposedly gave to the Chinese were trivial at best. Indeed, the Chinese probably gave away more technological secrets than they acquired from the U.S. companies that were working with them. The Chinese revealed technical details of their missiles, and we informed them about routine—and wholly unclassified—U.S. engineering practices. If the Chinese really wanted this information, it would have been easy for them to get. They could have requested government design specifications under a Freedom of Information Act request. They could have planted an agent at one of the companies or at a subcontractor. Or they could have surfed the Internet, where much of the information is readily available.

But the export control issue is hard for the general public to understand and easy for politicians and bureaucrats to spin. Supporters of controls argue that certain technologies can aid our adversaries. But they rarely ask the follow-up questions: Is it really possible to control these technologies? And at what cost?

|

|

Illustration by Taylor Jones for the Hoover Digest. |

Export Controls in the Real World

The recent preoccupation with export controls is ironic in that many of the critics of U.S. aerospace companies are libertarians and conservatives who defend free trade, free speech, and government accountability—and then turn around and support strict controls to restrict exports of so-called sensitive technology. Probably few of them have thought carefully about how their thinking on security clashes with their thinking on freedom. Probably even fewer have any direct experience in dealing with export controls in the real world. If they did, they would know that no government bureaucracy is more arrogant, unaccountable, and authoritarian than the one that oversees export controls—in other words, exactly the kind of martinets they complain about when they cite the dangers of too-powerful government.

The agency responsible for regulating exports with potential military applications is the State Department’s Office of Defense Technology Controls (ODTC). The State Department receives a request for technology exports and distributes it to other government agencies, which then approve, reject, or comment on the application. Before you can have a substantive discussion with a foreign engineer about any controlled technology, you need a "technology assistance agreement" (TAA). To send abroad a piece of hardware that is on the list of controlled technologies, you need an export license.

|

Last year, for the first time ever, European companies beat their U.S. competitors in sales of satellites to foreign customers. |

Ask engineers or executives in the aerospace industry about their experiences with ODTC, and they will respond with a roll of the eyes and several horror stories. Incredible as it may seem, some companies never even receive an acknowledgment when they submit an application for a TAA or an export license. At least the Internal Revenue Service answers its mail. ODTC officials routinely ignore requests for status updates on applications. Usually companies hire lawyers who specialize in cajoling bureaucrats to reach a decision on an application.

Even when companies make an honest effort to comply with the rules, it is easy to make mistakes because the rules about what constitutes "technical information" about a controlled product are broadly defined and open to debate. Also, under the law, if you can prove that information is in the public domain, then you can discuss it. But if the government charges a company with unauthorized disclosure of technical information, it is up to the company to disprove the charge. Indeed, the government often does not even have to prove that technical information—let alone hardware—was actually passed or caused any harm. Simply having a discussion with a foreign engineer can lead to a charge.

Consider a 1998 case involving the Boeing Company. Boeing was involved with two foreign companies in Sea Launch, a joint venture to launch rockets from an ocean platform. One of the partners was Yuzhnoye/PO Yuzhmash, a Ukrainian aerospace company, which provided the rockets. The other was Kvaerner Group, a Norwegian shipbuilder, which provided the platform. Boeing integrated the systems and marketed the services. In other words, with possibly a few minor exceptions, Boeing was importing hardware and receiving technical information. Nevertheless, the government claimed that, just by talking with Ukrainians and Norwegians, the Seattle engineers could have exposed secrets that threatened U.S. security.

|

The best way for the United States to influence the use of technology is to maintain leadership over its development. |

The Boeing episode exposes the worst features of current regulations. The government does not need to prove willful intent to impose a penalty. Indeed, the government does not even have to demonstrate that a violation caused any harm. And if a company fails to cooperate completely in an investigation of a violation—even a postulated violation—officials can stop action on every other export application the company has pending. Such an action could put a company like Sea Launch out of business. Little wonder Boeing simply paid its $10 million fine and got on with business.

How We Got Here

The real kicker is that there is little evidence that export controls work; indeed, they may be counterproductive in the long run. In fact, logic would lead one to conclude they are bound to fail in exactly the situations their supporters are most concerned about.

We take technology controls for granted today, but peacetime controls on nongovernment technology are a recent invention. True, the federal government often regulated the export of weapons during peacetime, and sometimes it controlled information about technology in wartime. But until the Cold War, no one tried to limit the flow of technical information developed by civilians with private money.

The first controls came in 1949, when the United States joined with 14 other countries (Japan, Australia, and all NATO members other than Iceland) to form the Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls (COCOM). The committee maintained a list of products that members agreed not to export to the Soviet Union and its allies. The goal was to protect the West’s advantage in military technology and to pressure the Soviet economy.

As the Cold War wound down in the 1980s, the Bush administration explored how to replace COCOM with a new set of controls. The Clinton administration—which had a greater faith in the ability of international organizations to guarantee security—pushed even harder. The so-called Wassenaar Agreement that emerged was supposed to keep states like Iraq, Iran, Pakistan, and North Korea from developing ballistic missiles and nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons. Alas, it has proven impossible to develop an agreement that all countries will accept. Wassenaar is supposed to control "dual-use" technologies—those that have both commercial and military applications. Unfortunately, almost any technology can be used for both peaceful and deadly purposes (your truck can easily be converted into the terrorist’s truck bomb). Also, there are too many countries that manufacture electronics and chemicals. As a result, the Wassenaar guidelines—which would likely be ineffective in any case—have no legal standing as a binding treaty.

|

The current approach to controlling technology will, in time, result in less influence for the United States—and less security. |

This is why U.S. export controls today are mainly a patchwork of laws and regulations left over from the Cold War. These controls are ill suited for current conditions. The old COCOM controls assumed the United States had a clear lead over the rest of the world in advanced technology. This is no longer true. Today many countries compete with the United States in aerospace and other controlled technologies. The French and Russians build advanced jets; the Israelis and Indians write software that competes with ours; and many countries are getting into bioengineering. It is hard to restrict technologies when you do not have a monopoly over them.

The old controls also assumed that government was ahead of the private sector in technology development. This was true during much of the Cold War but is rarely true today. Even government officials acknowledge that government has become a "technology borrower" rather than a "technology leader." The private sector has more capital, more minds, and less red tape. So, although the government still leads in a few niche technologies and in basic research (mainly because it does not need to worry about making a profit on its investments), the private sector dominates more fields.

Thus by the time government bureaucrats hear about a technology with potential military applications, researchers and businesspeople in the private sector usually know about it. Once that happens, it is difficult—or impossible—to control the technology without sealing the borders. Limiting the knowledge behind the technology is even harder.

|

There is little evidence that export controls work. Indeed, they may be counterproductive in the long run. |

Even if such controls could work, they would be a poor fit for the kinds of competitors and adversaries we face today. COCOM was based on an assumption that the Soviet Union was economically weak and could be pushed over the edge with enough pressure. However, countries such as China—the main target of the recent controversies—are economically strong. We are not going to defeat them by withholding supposedly sensitive technology.

More likely, the countries we target with technology controls will find alternative sources or they will develop the technologies themselves. Hundreds of millions of dollars are at stake. In one 1999 case, a Singapore company canceled a $450 million order with Hughes because it believed it would be prohibited from using a Chinese launch vehicle. And last year, for the first time ever, European companies beat their U.S. competitors in sales of satellites to foreign customers.

An Alternative Approach

During the Clinton administration, the White House and Congress argued over whether the Commerce Department or the State Department should have the lead role in regulating exports. This was, in effect, a debate over whether the federal government should be putting a higher priority on promoting trade or protecting security—or whether it should have an "easy-to-export" or a "hard-to-export" policy. This debate missed the point. The question is not whether we should be lax or tough on exporters. The question is how to balance costs, benefits, and risks. This is a routine question for regulation policy. The objective should be to treat export controls like other kinds of regulations designed to balance public interests with the interests of individuals.

|

Consider the State Department office that oversees export controls. There is no government bureaucracy more arrogant, unaccountable, and authoritarian. |

Indeed, one reason our current laws and regulations are so misguided is that they have unrealistic objectives. They are designed to eliminate any case in which a technology designated as sensitive might be released. Any regulation expert knows the problem a "zero defect" criterion creates: the corollary of zero defects is infinite costs. When no risk of compromising technology is acceptable, there is no limit to how much time and expense regulators can impose to protect technology.

Also, our methods for controlling exports have minimal public input and few requirements for transparency. It is hard to think of any other regulatory process that is so isolated and opaque. We have decades of experience in designing regulatory processes that avoid these traps. The only question is how to apply them to technology controls.

A good first step would be to focus our efforts on the technologies that are truly dangerous and have a good chance of being successfully controlled. One way would be to require only technologies developed by the government and classified at the top secret level or higher to be subject to formal review prior to export. This would concentrate the most stringent regulations on technology that is already tightly controlled. It would also recognize that, once a technology is in the private sector and widely known, it is difficult or impossible to control.

A second step would be to create a technology control commission (TCC), which would monitor and regulate technology exports the same way the Federal Communications Commission regulates the use of the airwaves. As is the case with the FCC, the president would nominate the TCC chairperson, and the majority and minority leaders in the Senate and House of Representatives would each nominate a commissioner. Commissioners would serve for fixed terms. Regulations controlling exports of technical information would be subject to public hearings, would require a majority vote of the TCC, and would include a sunset clause requiring their periodic review and renewal.

This approach would improve accountability. Also, if both the executive and legislative branches of government had a say-so in developing and overseeing technology regulation, there would be less demagoguery when controls failed. Creating a TCC would also concentrate the review process in a single body and avoid many of the delays the current system creates.

Finally, the entire export control process should be brought within the rule of law. Investigation of potential violations should not proceed unless officials can demonstrate prior cause. Government officials should be required to demonstrate damage before violators are penalized. All export restrictions should have meaningful sunset clauses. When controls expire, the TCC should be required to repeat the review process, including public hearings.

Those who argue for technology controls need to remember that the best way for the United States to influence the use of technology is to maintain leadership over its development. Similarly, the best way to gain insights into how foreigners are using technology is to allow American companies to remain engaged with them. The current approach to controlling technology will, in time, result in less influence for the United States, less insight—and less security.