- Education

- K-12

- State & Local

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

If there’s one memorable lesson from the release in October of the 2005 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) results in reading and math, it’s a timeless one: Incentives work. They alter behavior in education and government, just as they do in capitalism. Unfortunately, they don’t always alter behavior for the better.

On the positive side, the 2005 NAEP scores for African American, Hispanic, and poor children were slightly higher than in 2003, thereby narrowing a bit the nation’s long-standing “achievement gaps.” Among fourth-grade students the average scores of black youngsters bumped up two points in reading and four in math (on a 500-point scale). Hispanic students gained three points in reading and four in math, while low-income children rose two points in reading and three in math. All those gains are “statistically significant” and are good news for our democracy and society.

The president’s much-discussed No Child Left Behind Act can take some credit for the modest gains of the past two years. By holding schools to account for the learning of all their students, especially minority and needy children, the law has captured the attention of educators nationwide. One hopes (and the data imply) that schools are raising expectations, redistributing resources (such as quality teachers), and putting their noses to the grindstone in order to help disadvantaged youngsters achieve basic standards in reading and in math (and to avoid the harsh sunlight, embarrassing comparisons, and unwelcome sanctions of the federal law).

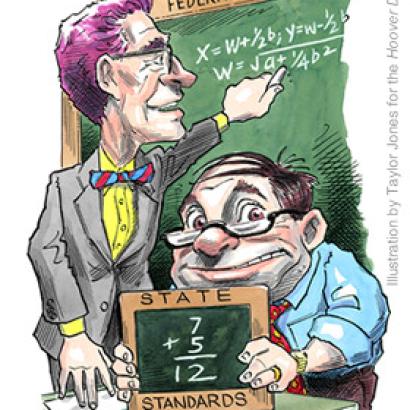

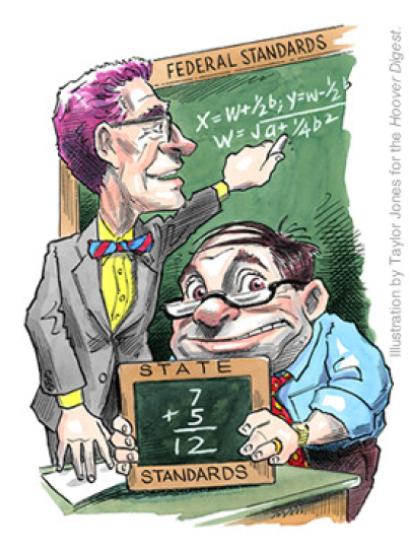

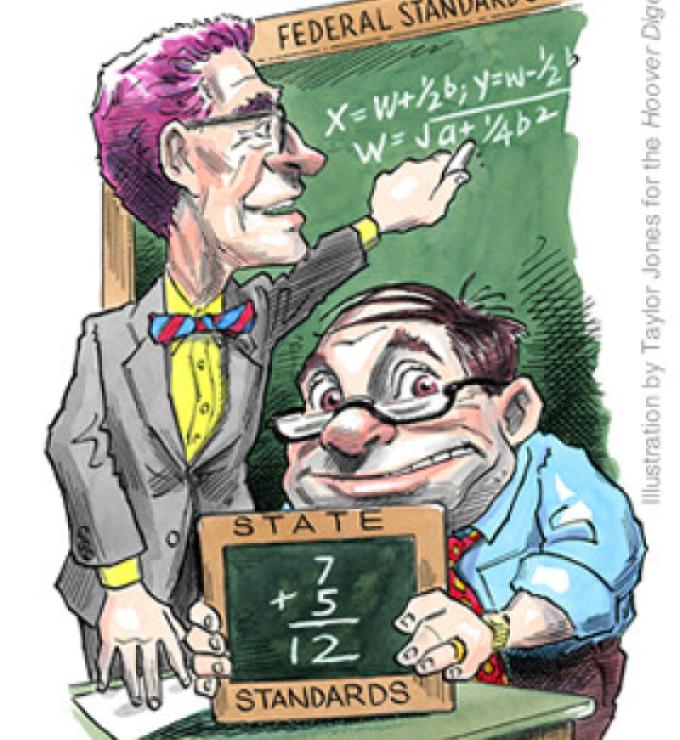

But there are perverse incentives at play here, too. No Child Left Behind seeks to help all students reach “proficiency” by 2014 and requires states to develop tough accountability systems to ensure that their schools are making progress toward that end. (If schools are not progressing, they face a cascade of interventions, exiting students, and other consequences.) But here’s the catch: The states define “proficiency” however they like. So if you’re a governor or education commissioner, and you want your state’s schools to look good, you have a strong incentive to relax your definition of “proficiency” in reading and math and make your own state tests easier. Last week’s good news is shadowed by early evidence that some states may be doing just that.

We analyzed data from state tests as well as the national assessment and looked at states’ progress on both over the past two years. The result? Nineteen states (of the 29 with available and comparable data) reported their eighth-grade students made progress on state reading exams. But only three of these states show any gains on NAEP and, even then, only at the “basic” level. (Eighth-grade NAEP reading results were disappointing almost everywhere, and the national average fell by a point.)

Consider Arizona. Its own test results show the number of eighth graders proficient in reading rose 8 points (from 55 percent to 63 percent) between 2003 and 2005. Yet the percentage of Arizona eighth graders scoring at NAEP’s “proficient” level actually fell two points during the same biennium. (The percentage of Arizona’s students reaching NAEP’s lower “basic” level also dropped by a point.)

States may say that such discrepancies merely reflect the different subject matter they test versus the content assessed by the feds. California, for example, has laudably rejected “whole language” reading instruction and other faddish ideas that have partially infected the national test. Perhaps this is why the Golden State posted gains of nine points in its proportion of eighth graders reaching proficiency on reading, whereas its percentage of students reaching “basic” and “proficient” on NAEP dropped a point each. But surely that’s not the case for all states. The larger trend line is clear: The news is much rosier if you believe state reports than if you believe the national assessment.

What about the concern that the federal law, by focusing on students at the lower end of the achievement range, will give educators incentives to ignore top-performing pupils? Here the news is mixed. In reading, there’s disturbing evidence that our top students are stalling; those at the 90th percentile have lost ground in both fourth and eighth grades since 2003. In math, however, students at all levels showed progress. This is something to watch in future years. Although closing the achievement gap is a priority, so is closing the “economic competitiveness” gap with other nations. We can’t afford to zap the talent of our most gifted kids.

Behaviorism is at least as risky in public policy as it is in psychology. When Washington knowingly holds out carrots and sticks, sunshine and sanctions, to alter the established practices of states, districts, schools, and teachers, unintended and undesirable changes are at least as likely to result as the kind that lawmakers expect.