- History

- Military

- Contemporary

- US

One of the most memorable lines from the recent presidential campaign was offered by the GOP frontrunner and eventual nominee: “We give state dinners to the heads of China. I say ‘why are you doing state dinners for them? They are ripping us left and right. Take them to McDonald’s and take them back to the negotiation table!’ Seriously!”

That was candidate Donald Trump speaking at a campaign rally in Sun City, South Carolina, on July 21, 2015.

Next week, President Donald Trump will host a state visit by President Xi Jinping, the Supreme Leader of China, at his Mar-a-Lago mansion in Palm Beach, Florida. It is perhaps not going to be a state dinner in a technical sense, but it will certainly not be double cheeseburgers at McDonald’s either.

Perhaps realizing his discomfort with regards to how he really feels about negotiating with China’s leaders and what diplomatic protocols he must afford to his guests, President Trump tweeted a few days before Xi’s visit, “The meeting next week with China will be a very difficult one in that we can no longer have massive trade deficits and job losses. American companies must be prepared to look at other alternatives.”

President Trump’s admonition that American companies might seek “other alternatives” makes his presidency a revolutionary deviation from a well-established, albeit peculiar, tradition for extravagant expressions of profound respect for China and its leaders.

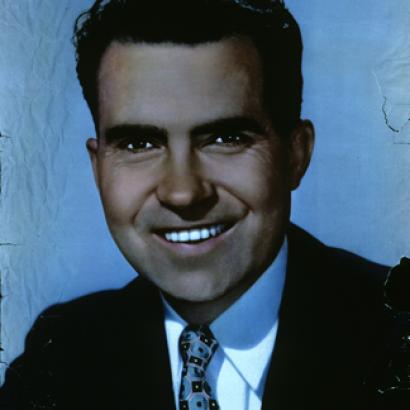

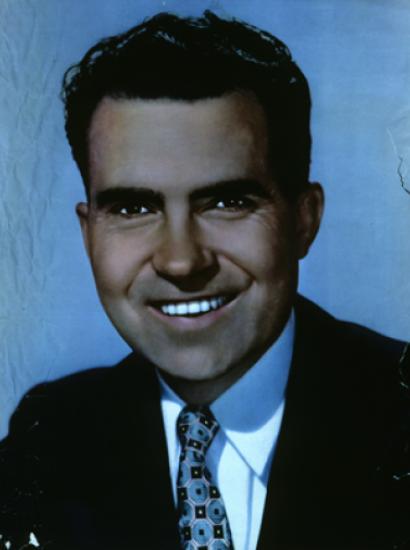

That tradition started in 1972 with President Richard Nixon whose extraordinary hype of the preeminence of the Sino-U.S. relationship set in motion a cult policy of all-out engagement with China, dogmatically carried out ever since by the previous eight presidents—until President Trump.

Nixon’s China hype was rooted in incidental circumstances but not in the inexorable logic of history. His historic 1972 trip to China was motivated, broadly speaking, by three factors, namely, the desire to seek China’s help in fulfilling his 1968 campaign promise to get the U.S. out of Vietnam; the urgency of getting re-elected in 1972 which required tangible progress in a Vietnam pullout; and the tactic of “Playing the China Card” to further upset and isolate the Soviet Union.

The incidental nature of the Nixon initiative to “open up” China would have given the U.S. much coveted flexibility and diplomatic mutability to embrace new changes and developments in the bilateral relationship. But the Chinese leaders pounced on Mr. Nixon’s eagerness for help and vigorously objected to the incidental nature of the new U.S.-China relationship. Instead, they insisted that the compromises and non-confrontational nature of Nixon’s China initiative must be made inexorable and immutable by way of a series of “communiqués” that have served to prevent the U.S. from adapting to new circumstances and developments.

As a result, while the incidental circumstances that propelled Nixon to go to China have all disappeared—the Vietnam war, the 1972 re-election exigency, and the existential threat posed by the Soviet Union—the diplomatic straightjacket codified by these “communiqués” and the non-confrontational, some might say, unprincipled, nature of the overall Nixonian approach to China have become permanent with an army of loyal defenders, mostly from the upper crust of the American mandarin class.

On the other hand, extraordinary new circumstances have occurred, to which the U.S. has been unable to adapt successfully. Since Nixon, Taiwan has become a free society and a vibrant democracy that deserves America’s full recognition, while China remains a Marxist-Leninist one-party state, whose predatory economic, trade, and currency policies have made it the only nation that is challenging America’s economic as well as military preeminence in Asia and the Pacific region.

The Trump presidency provides the first real chance in more than four decades to get the U.S. out of the self-imposed Nixonian diplomatic straightjacket and to deal with China on a brand new platform, with the painful but necessary admission that the U.S. might have played the China Card against the Soviet Union briefly, but it is China that has been playing the “U.S. Card” all along, brilliantly, without interruption, and without mercy.