- History

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

I. U.S. Doctrines from Washington to Obama

Foreign policy doctrines are as American as apple pie, and as old as the Republic. Start with George Washington’s Farewell Address: The “great rule” in dealing with other nations was to extend “our commercial relations” and “to have with them as little political connection as possible.” So stay out of Europe, and keep Europe away from us.

Echoing Washington, Thomas Jefferson promulgated the “no-entangling alliances” doctrine. John Quincy Adams decreed: “America does not go abroad in search of monsters to destroy.” James Monroe told off the Europeans: Stay out, the Americas are for the Americans, North and South. Teddy Roosevelt doubled down by proclaiming the right to intervene in Latin America.

Harry S. Truman went global. The U.S. would support “free people who are resisting … subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures.” So did Dwight D. Eisenhower: He would commit U.S. forces “to secure and protect” all nations against “overt armed aggression from any nation controlled by international communism.” John F. Kennedy famously declaimed: “We shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, in order to assure the survival and the success of liberty.”

LBJ built on Monroe and TR: The U.S. would intervene in the Western Hemisphere when “the establishment of a Communist dictatorship” threatened. The Nixon Doctrine pledged to shield each and all “if a nuclear power threatens the freedom of a nation allied with us or [one] whose survival we consider vital to our security.”

Jimmy Carter defined any “attempt by any outside force to gain control of the Persian Gulf region “as an assault on the vital interests of the United States,” which “will be repelled by any means necessary.” Ronald Reagan would aid all those who “are risking their lives...on every continent, from Afghanistan to Nicaragua ... to defy Soviet aggression.”

Bill Clinton promulgated obligation wrapped in realism. “We cannot, indeed, we should not, do everything or be everywhere. But where our values and our interests are at stake… we must be prepared to do so.” In particular, “genocide is … a national interest where we should act.”

The Bush Doctrine, enunciated during the “unipolar moment,” covered the whole waterfront. It was to be preventive war “before threats materialized.” Nations harboring terrorists would be a target of war. In global affairs, it was unilateralism. Plus, most ambitiously, regime change: “The defense of freedom requires the advance of freedom.”

Barack Obama is the odd man out. He rejected a “doctrinaire” approach to foreign policy. But when pressed, he replied: “The doctrine is we will engage, but we preserve all our capabilities.” Translated: We will go low on force and resist sweeping ambitions. “Obama entered the White House bent on getting out of Iraq and Afghanistan,” the Atlantic’s Jeffrey Goldberg reported after a series of conversations with the President; “he was not seeking new dragons to slay.”

According to Goldberg, Obama was loath to “place American soldiers at great risk in order to prevent humanitarian disasters, unless those disasters pose a direct security threat to the United States.” Instead of intervention, it was retraction. Obama confided that he would rather deal with “climate change,” which is an “existential threat to the entire world if we don’t do something about it.”

Obama’s angst was the overextension to which “almost every great power has succumbed.” Retrenchment and strategic reticence were the hallmarks of the (unarticulated) doctrine. He opposed “the idea that every time there is a problem, we send in our military to impose order. We just can’t do that.” (All quotes from “The Obama Doctrine,” The Atlantic, April 2016) What could and should we do? “Come home America,” George McGovern famously cried out in his 1972 campaign. Forty years later, Obama’s mantra ran: “It’s time for a little nation-building at home.”

II. Where Does Trump Fit In?

In Riyadh in May, Donald Trump explicitly defined his approach as “principled realism, rooted in our values, shared interests, and common sense.” He continued:

Our friends will never question our support and our enemies will never doubt our determination. Our partnerships will advance security through stability, not through radical disruption. We will make decisions based on real world outcomes, not inflexible ideology. We will be guided by the lessons of experience, not the confines of rigid thinking. And wherever possible, we will seek gradual reforms, not sudden intervention. We must seek partners, not perfection. And to make allies of all who share our goals.

These nicely balanced cadences could have been uttered by any postwar president. Trump hit all the classic notes. So what about the differences? Interestingly, “principled realism” was not so much directed against Barack Obama as against fellow-Republican George W. Bush. No more “radical disruption.” Gradual reforms must beat out “sudden intervention.” Unlike Obama, Trump would not to be choosy when recruiting allies. Hence, “we must seek partners, not perfection.”

Truman and Eisenhower, JFK and LBJ would have nodded. In the Cold War, none of them had any moral qualms when picking allies against the Soviet Union. As long as “our” strongmen demonstrated fealty to the U.S., they were all welcome: dictators in Spain and Portugal, potentates throughout the Middle East, and caudillos in Latin America. Like Obama, Trump will not be “doctrinaire.” Hence his emphasis on the “lessons of experience” and the rejection of “rigid thinking.” Who would want to quarrel?

Ironically, there is more continuity between Obama and Trump than meets the eye of the media. Obama had told UK prime minister David Cameron: Never mind the “special relationship,” “you have to pay your fair share.” Trump told a NATO summit: “Twenty-three of the 28 member nations are still not paying what they should be paying for their defense.” This is “not fair” and “many of these nations owe massive amounts of money.”

Who said: “Free riders aggravate me?” That was Obama, not Trump. Trump also could have tweeted this Obama line: “You could call me a realist in believing we can’t … relieve all the world’s misery.” The Founding Fathers and John Quincy Adams would applaud.

American presidential doctrines are tricky. In his 1916 campaign, Woodrow Wilson ran on a plank that proclaimed: “He kept us out of the war.” Six months after his re-election, he launched a war against Kaiser Bill to “make the world safe for democracy.” Obama reduced U.S. troops in Europe to 35,000. At the end of his second term, though, he started redeploying men and materiel. Given Trump’s anti-NATO rhetoric, one might have expected him to stop the flow. He did not. The deployment continued with the dispatch of a Stryker battalion to Poland as part of a multinational battle group.

Recall that No. 45 had previously denigrated NATO as “obsolete,” and the EU as a failing business (it “is gonna be hard to keep together”). Recall also that at the Brussels NATO summit in 2017, the president demonstratively declined to affirm Article 5 that commits all members to come to the aid of an attacked ally. Yet the heads of Defense and State, Jim Mattis and Rex Tillerson, went out of their way to praise NATO and underscore the U.S. security guarantee. The vice-president celebrated America’s “unwavering commitment” to the Alliance., while Jim Mattis affirmed “our enduring bond.”

Ironically, Art. 5 has been invoked only once—and then in favor of the U.S. after 9/11. If North Korea launched missiles against America, the U.S. again would be the beneficiary of Art. 5. “Obsolete” was yesterday, and suddenly Trump was “totally in favor” of the EU.

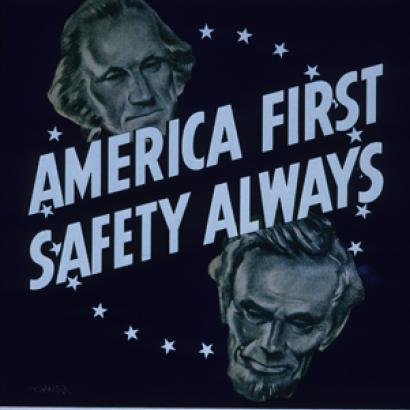

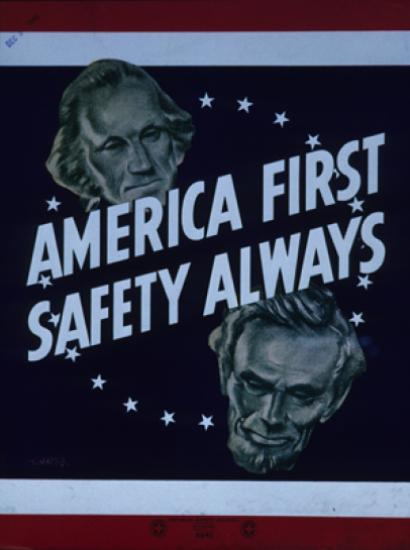

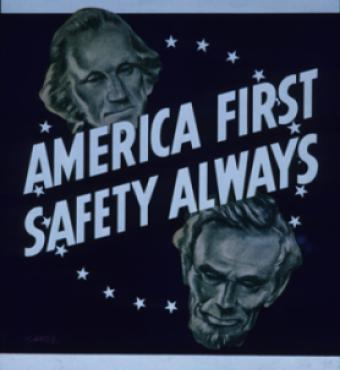

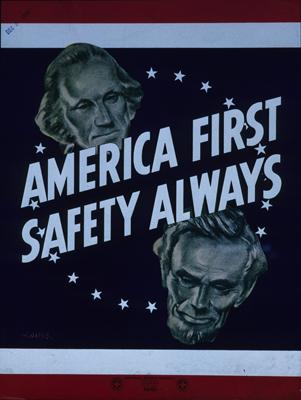

Trump has been fingered as an isolationist. “America first” seems to corroborate the point, and the “free rider” label would apply to both Europe and the Far East. So shape up, or we ship out. But reality bites. As North Korea stoked the fires of aggression, Trump tightened the alliance bonds with Japan and South Korea. THAAD, the Army’s Terminal High Altitude Area Defense, went to South Korea in May 2017 to signal to Pyongyang: The U.S. will defend Seoul against your missiles.

The administration also stepped up naval patrols in the Western Pacific to counter Beijing’s ambitions. In the Syrian War, it is “Obama-plus”: No overt boots-on-the-ground, but plenty of bombing against ISIS, which Obama had ridiculed as a “Jayvee Team.” Bombing runs against ISIS have substantially increased under Trump. Instead of vacating “red lines” in Syria, as Obama did, the U.S. launched missiles against a suspected chemical weapons facility.

It is also Obama-plus on Iran, the “plus” referring to Trump’s harsh rhetoric against Tehran’s nuclear weapons program. The bet, even odds, is that the U.S. will not abrogate the JCPOA, the deal that is to brake Iran’s nuclear effort. Nor does Trump divulge his strategy for dealing with the most urgent issue, the expansion of Iranian and Russian power across the Middle East. Ironically, the U.S. engagement against soon-to-be defunct ISIS has cleared the way for Russia and Iran to secure a permanent foothold in the Levant. Henry Kissinger, who expelled the Soviet Union from the Arab world half a century ago, would not approve.

III. What Then is “Principled Realism?”

As far as U.S. doctrines go, the Trump version owes more to Obama than to W. With his sweeping agenda, Bush was no realist because he ignored the difference between ambition and achievement as well as the gap between limited means and unbound ends, like implanting democracy in a barren Arab soil. Obama’s lodestar was the retraction of U.S. power; only at the end of his second term did he come to understand that great powers do not enjoy the choice of self-containment.

Trump, paradoxically, followed in Obama’s footsteps, denigrating humanitarian and regime-change intervention. Instead, he touted “America first,” an America that looks out for itself and flattens its profile in the world. Yet beware of doctrines and scrutinize actions. Trumpism does not spell the retrenchment of American power, but its re-assertion around the globe. Still, the weight of American strategy has definitely tilted from ideals to self-interest. “Reassert yourself big-time, but mind the risk and look for a deal with your rivals”—this might be the gist of a Trump Doctrine in the making.

In contrast to Trump’s overblown rhetoric, his behavior is actually quite restrained, as befits a great power that must constantly weigh risks against rewards. Nor does “America first” spell isolationism. Trump has reaffirmed alliance commitments and put his troops and missiles in harm’s way, in Europe as well as in the Pacific. His bluster belies his caution. He could almost quote Obama who famously proclaimed: “Don’t do stupid shit.”

What is the difference between Nos. 44 and 45? Obama did not believe in American power, Trump does; but he is not given to visions of omnipotence, as was George W. Bush. If there is a Trump Doctrine beyond the measured cadences of his Riyadh address, it is not “no-force,” but the “economy of force.” Balance means and ends, size up present and future costs, don’t go into open-ended wars, deter your enemies and protect your friends who might look like free riders, but actually amplify American power.

In his first year, No. 45 fails on rhetorical restraint, but gets decent grades on the real-life tests. It is as if there were two Trumps. One threatens South Korea with the abrogation of a free-trade pact in force since 2007. The other simultaneously deploys anti-missile systems to defend the South against an attack from the North. Trump One roars, Trump Two reassures.

While the Europeans have calmed down on their security fears, what with Trump retightening the Atlantic bond, they—and America’s Asian allies—still shiver when it comes to the international economy. Who will prevail? The bad Trump who is putting the axe to the liberal trading order the U.S. built and maintained for 70 years? Or the good Trump who understands that protectionism and trade war will damage America’s economic welfare along with the well-being of its allies.

One year into Obama’s first term, strategic retrenchment was already visible. But his administration was bullish on free trade, as exemplified by the pursuit of the Atlantic and Pacific free-trade pacts. Trump has nixed the latter, while allowing the Europeans to sink the former. If the prudent Trump prevails over the blustering one, realism and the sound calculation of U.S. interests may yet reassert themselves in the international economy—as they did in the arena of grand strategy.