When he was born in the backwoods of Kentucky, there was absolutely no sign, nor reason to believe, that Abraham Lincoln would ever amount to much in public life, much less grow up to be one of the most consequential leaders in our nation’s history. Yet, from those very humble origins, that’s exactly what happened. This essay, the final of four on Lincoln, focuses on his actions during the war, especially as the North was completing its military victory over the South, and how these somewhat unpopular (but wise) decisions, in both the military and political domains, supported his vision for a united country going forward.

As he stated in “The Gettysburg Address,” he saw the conclusion of the bloody Civil War as an opportunity for a “new birth” for the nation, fully committed to the vision of the Founding, but now finally free from moral scourge of slavery. [1] Lincoln believed that if we concluded the war the right way, we would be able to once again find common purpose as a nation and reawaken the spirit of Philadelphia. Lincoln envisioned a future America united and fully prepared to tackle the many challenges of an accelerated Industrial Age. While the saying, “we shall not see the likes of him ever again,” is overused in our country today, for Lincoln it just seems apt. He was the very embodiment of the American Dream and used his platform to protect and strengthen this cherished way of life. With his assassination, American Common-Sense Realism, our Founding political philosophy, went into decline as we buried our last Founding Father.

Lincoln’s commitment to Founding principles was evident throughout his life and clearly visible from the beginning of his tenure as president. When the country gathered to inaugurate our sixteenth president on that fateful day of March 4, 1861, Lincoln inherited the herculean task of finding a way to put our nation back together again. On day one, he faced a constitutional crisis brought on by the secession of a number of southern states who left the Union in the months following the November election. Few expected Lincoln would have the answers, but this man had strong convictions and a vision inspired by the Founders. Along with these redeeming qualities, Lincoln possessed exemplary temperament and displayed wise judgment. In the toughest of times, Lincoln’s determination, toughness, courage, integrity, and flexibility—all the stuff of consequential leaders—carried the day.

Self-taught and widely read, Lincoln admired the Founders’ effectiveness at finding compromise and forging common purpose. The respect he had for that philosophic approach informed his decisions as he assumed the office of the presidency and inspired him to reach out one final time to the South in hopes of peacefully resolving the crisis of secession. Lincoln admired the way the Founders overcame significant differences to pass the Constitution in Philadelphia in 1787, and he hoped to recreate that magic in the midst of his crisis in the spring of 1861. The Founders, too, struggled with the issue of slavery because all delegates knew securing Southern support for the Constitution was essential for ratification of the new legal framework. Without Southern support, there would be no United States of America. Still, despite facing that political reality, Lincoln was convinced that the Founders intended to put slavery on a path to extinction. That’s why they included the stipulation on an importation ban in the Constitution and why the Continental Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance prohibiting slavery in the territories that same year.

In his positioning, Lincoln was endeavoring to recover that thoughtful and nuanced approach. It was important both to ensure slavery was on a path to extinction and to peacefully restore the Union. Ultimately, he wanted to create a national environment where all States and citizens could flourish—to live up to our highest aspirations expressed in the Declaration of Independence. As for the details to achieve these daunting challenges, Lincoln was open to creative ideas and flexible timelines; but he insisted that the slavery question had to be resolved and that the Union must be made whole.

As I have outlined in my previous three essays, once peaceful efforts to resolve the crisis proved futile and the war commenced, Lincoln exercised his leadership with Congress, the Cabinet, and the U.S. military to accomplish his vision. This final essay argues that Lincoln’s sometimes overly charitable decisions, appearing to cater to all interests at the risk of pleasing none, were more inspired by his understanding of Founding philosophy and aimed to bring about a rebirth of the country consonant with it.

Even under acute stress of the war, from the very beginning Lincoln modeled the spirit of Philadelphia, picking a Cabinet that one historian characterized as a “Team of Rivals.”[2] Especially with regard to William Seward and Salmon Chase, these were his fierce political rivals as he was rising in the newly formed Republican Party, selecting them for the cabinet was a bold decision and certainly sent a message and tone for his administration. Lincoln was always attempting to strengthen the team—the American team. From a very young age, Lincoln cultivated keen listening skills and was very adept at forging social bonds with others, and these traits and competencies helped him during the war. Lincoln would rather have a rival on the inside of his administration helping him think through problems and issues divergently and creatively than on the outside fomenting trouble. Of course, this is easier said than done. It takes great self-confidence to surround yourself with those who strongly oppose your views, but for Lincoln this was also part of his strategy to build consensus—first among splintered political factions in the North, and then later, across the entire nation. This approach was very aligned with Founding thinking and processes as the Constitution itself was a compromise, intended to drive future compromises, and forging consensus is at the heart of functional government for a republic “of the people, by the people, for the people.”[3]

Although his Democrat rivals in Congress often labeled him as a would-be dictator, sometimes with arguable cause as when he initially suspended Habeas Corpus without Congressional approval, Lincoln generally remained thick-skinned, constantly looking for opportunities to work together and bring them along where he could. Moreover, Lincoln’s political challenges were not limited to his political opponents. Even within his own political party, where ideological differences were so large and apparent it was impossible for Lincoln to please everyone, too often he felt like he was pleasing no one. As mentioned in a previous essay, Lincoln nearly lost the renomination over this dynamic, but his temperament kept him from panicking, and in retrospect, that generosity of spirit allowed all factions of this far-flung governing coalition to freely express themselves, which history records had cathartic value. This ultimately helped our nation continue to move forward in the face of adversity, even though at times it appeared that chaos would consume the moment.

Although Lincoln was very aware of the broad expansion of executive authority provided by the Constitution during times of rebellion, where he could, he still worked with the Congress to effectuate political change in accordance with the letter and spirit of that legal framework. We see this on the matter of slavery as even after his Emancipation Proclamation, he continued to work with the Congress (and the states) to pass (and eventually ratify) a Constitutional Amendment to permanently codify it in accordance with our constitutional process. Similarly, after initially effectuating a regional suspension of Habeas Corpus in 1861 (and paying a price for that politically), Lincoln waited until after Congress passed a law in 1863 authorizing it before extending that suspension nationwide in narrow circumstances.

Importantly, unlike in Ukraine today, which has suspended national elections due to the war with Russia, Lincoln resisted the temptation to cancel elections in the North, despite the rebellion. His unshaken confidence in the democratic process was reassuring and gave hope for eventual national unity. Related, although the North was obviously at war with the South over secession, and the South was overwhelmingly supportive of the Democratic Party, Lincoln consciously selected a Democrat as his running mate as he prepared for re-election in 1864, in a clear effort to signal his willingness to work with everyone to unify the country after the war.

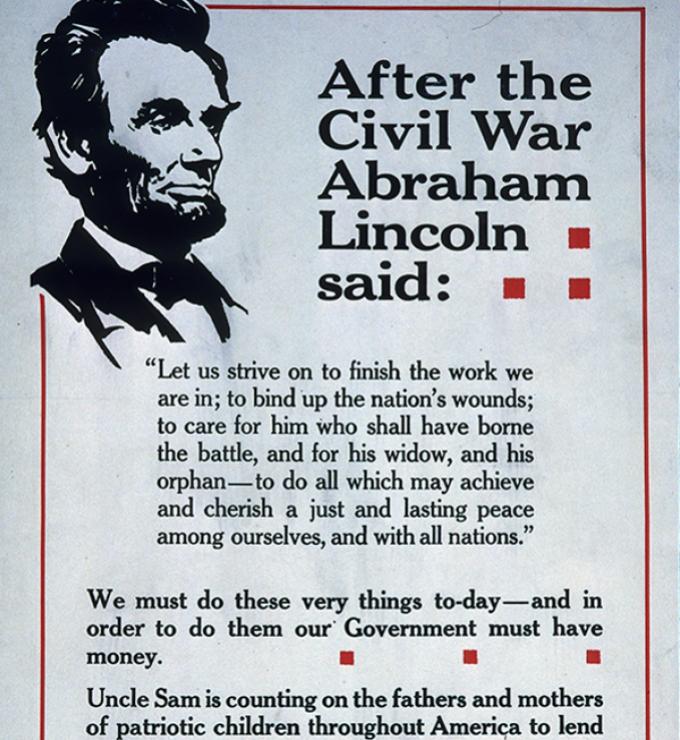

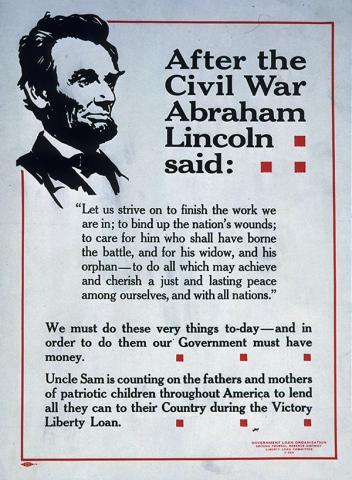

This is how we should perceive the message of his Second Inaugural Address (“with malice towards none and charity towards all”) and his merciful terms for surrender for the South. Lincoln, who had survived the darkest days of the war and by 1864 had finally found the winning strategy and generals to implement it, was preparing the country for a just and lasting peace. He was fully committed to uniting our country under the political philosophy of the Founding empowered by the spirit of Philadelphia. By finally resolving the first-order moral question of slavery, Lincoln planned to strengthen the dynamic process of compromise and peaceful, evolutionary change created by the Founders when they ratified the Constitution.

With Lincoln’s death, we mourned our last Founding Father. Since that day, our country has seen the waxing and waning of various political ideologies (conservatism and liberalism), cultural movements (like populism), and a new political philosophy (progressivism), but the shared political philosophy (American Common-Sense Realism) that the entire country embraced for the first 75 years of the republic has never been the same. That unifying philosophy was strongly supported by such divergent thinkers as John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, and even Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis, but since the Civil War it has never regained its standing and we are worse off for that.

You can read my book to learn more about all this, including my plan to recover it.

Chris Gibson is a decorated Army combat veteran, a former Member of Congress, and a Participant of Hoover’s Working Group on the Role of Military History in Contemporary Conflict. This essay was drawn from Gibson’s latest book, The Spirit of Philadelphia: A Call to Recover the Founding Principles, published by Routledge in 2025.

[1] A direct quote from the final sentence in Abraham Lincoln’s iconic “The Gettysburg Address,” delivered in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania on November 19, 1863.

[2] Doris Kearns Goodwin, Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005).

[3] “The Gettysburg Address,” as Lincoln echoes the spirit behind both the Declaration of Independence and the Preamble of the Constitution.