Alliances matter. Not even superpowers can go it alone. Today alliances around the world are shifting, and not always in America’s favor. To be sure, there has been some good news for the United States and its friends.

The Ukraine War has revived NATO as an alliance and (largely) unified it in support of Ukraine. Meanwhile, the formerly neutral Finland and Sweden applied for membership in NATO: Finland joined in April, while Sweden awaits approval by Turkey’s parliament, no doubt after further negotiation.

The Middle East as well has seen significant realignments. The year 2020 marked the signing of joint normalization agreements between Israel and three Arab countries, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates, followed by Morocco, the so-called Abraham Accords.

The U.S. has also engaged in closer relations with both formal and informal allies in the Indo-Pacific region in the wake of Chinese expansion. Americans describe China as “the pacing threat,” both regionally and globally.

But by the same token, America’s rivals have been on the move.

In February 2022 the presidents of China and Russia, Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin, met and signed a statement declaring that there were “no limits to Sino-Russian cooperation.” Twenty days later, Russia invaded Ukraine. Both China and Russia have reached out to Iran. Putin’s Russia has worked with Iran for years in pursuit of common interests in Syria and the Caucasus. Iran has provided drone technology and artillery shells to Russia for use against Ukraine. There is speculation that Russia is providing Iran with nuclear expertise and technology, if indeed Iran, with its advanced nuclear program, needs any. Iran and Russia, often along with China, work together to a certain degree to network with like-minded states such as Cuba, North Korea, Syria, and Venezuela. They share a hostility to what Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov in 2022 called “the collective West.”

In March of this year, China surprised many by announcing that it had negotiated an agreement between Iran and Saudi Arabia to restore diplomatic ties after seven years of cutting relations. China is Iran’s largest trading partner and has a strong interest in Iranian oil. The Biden administration has responded by negotiating what may possibly lead to an Israeli–Saudi normalization agreement, but from the American point of view, the most important part of the deal involves the Saudis and China.

The U.S. had chilly relations with the Saudis in response to the 2018 murder of dissident Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, a U.S. resident, at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul. American intelligence concluded that Saudi crown prince, Muhammad bin Salman, approved the murder. But, focused on its rivalry with Beijing, Washington does not want to see the Saudis move into China’s camp, so the Americans are trying to initiate a thaw. It has been reported that the U.S. is offering significant concessions in exchange for Saudi promises not to let China build military bases in the kingdom and not to use Chinese currency (as opposed to the U.S. dollar) to price oil sales, as well as to limit the use of China’s Huawei technology. Among them are an iron-clad security guarantee for the Saudis and assistance with developing a civilian nuclear program (which, a cynic might say, could one day be used to counter Iran’s “civilian” nuclear program). There is also meant to be an agreement for Saudi Arabia to recognize Israel in exchange for Israeli concessions to the Palestinians, but that seems less central to the Americans, and less likely to happen.

By the same token, Washington has struck a deal with Iran for a prisoner exchange and $6 billion. The Americans insist that these are all humanitarian moves (Iran cannot use the funds for military purposes, although they may of course choose to free up other Iranian funds for those ends). There is speculation that the deal marks progress towards the Biden administration’s goal of reentering a nuclear accord with Iran. For what it’s worth, the day after the prisoner swap was announced, it was reported that Iran is cutting back on its nuclear enrichment.

The pace of change may be rapid today, but a shift in alliances is nothing new. History records many cases. August 23, for example, marks the 84th anniversary of the Nazi–Soviet pact in 1939. This agreement between two former archenemies opened the way for a German invasion of Poland, which followed nine days later, on September 1. Russia invaded Poland in turn a little over two weeks later and gobbled up the eastern part of the country. It was, in effect, a new partition of Poland. In addition, the Soviets annexed the three Baltic states, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, as well as the northeastern parts of Romania, that is, Northern Bukovina and Bessarabia. Free of any military threat on its eastern border, Germany proceeded to conquer first Denmark and Norway and then Belgium, Luxemburg, the Netherlands and, most consequential of all, France. World War II was in full swing.

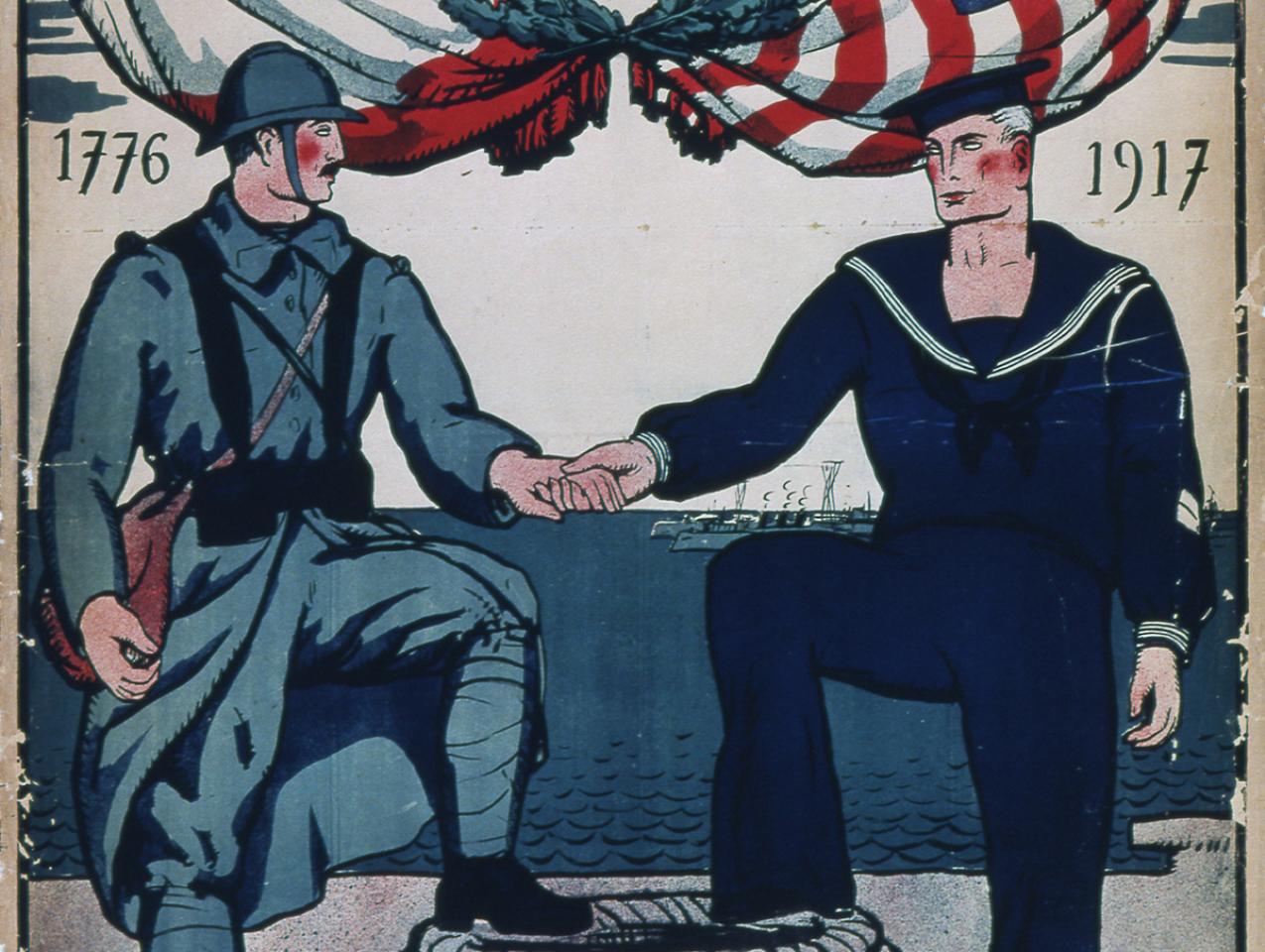

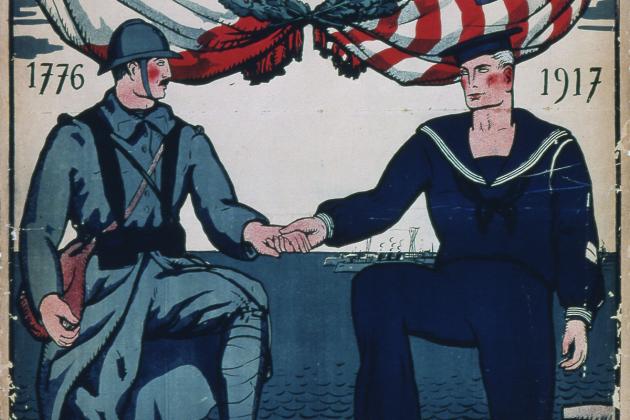

History is full of sudden changes in alliance, beginning in classical Greece, when longtime enemies Athens and Sparta joined forces against the rising power of Thebes. More recently, the British colonists of North America went from armed hostility against France to friendship. The Franco–American alliance, signed in 1778, played an outsized role, arguably the decisive role in the winning of American independence. Yet two decades earlier, the Seven Years War, a global conflict between Britain and France, began when an obscure, 22-year-old lieutenant-colonel in the Virginia militia ambushed a French detachment in the western Pennsylvania wilderness. His name: George Washington.

As alliances shift, today as in the past, the storm of war may follow. It has already begun in Ukraine. Students of history ought to be clear-eyed about the dangers ahead.

Barry Strauss is the Bryce and Edith M. Bowmar Professor in Humanistic Studies at Cornell University, Corliss Page Dean Visiting Fellow at the Hoover Institution, and author most recently of THE WAR THAT MADE THE ROMAN EMPIRE: Antony, Cleopatra, and Octavian at Actium (Simon & Schuster).