- Education

- US

- Contemporary

- Law & Policy

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Civil Rights & Race

- History

There are very few photographs of my dad as a child. The only two I have seen are his christening picture—a baby boy engulfed in a lacy white dress—and another of him, aged seven or so, with his father, both in baseball uniforms. My grandpa Earl, of the Northwood Team, is down on one knee, leaning on a massive wooden bat. Young Russell, meanwhile, stands beside him wearing the baseball outfit his mother sewed for him, one hand on his dad’s shoulder, the other holding a slimmer bat, grinning ear to ear. Religion and baseball— those were the two commemorated moments of cultural transmission.

There are oodles more pictures of me as a child. But two of my favorites are baseball photos: one of me, less than a year old, cradled in my dad’s arm, watching a baseball game; another of me and my sister in our Minnesota Twins jackets being taught to throw—not like girls—by our dad.

Because of the way in which baseball links the generations it has been a channel through which vital traits of American character are instilled. The health of baseball concerns all of America, and the health of America— perhaps especially the American family—finds itself reflected in the state of our national pastime. Baseball is a mirror of American liberty and of the virtues necessary to sustain it.

THE DEMOCRATIC GAME

Preferring to be nonjudgmental, Americans don’t give much thought to the moral effects of various sports and games. Of course, we have a general notion of sportsmanship. Good sportsmanship is a virtue that can be displayed in any activity that involves victory and defeat. But there are also more subtle effects on character wrought by how we exercise our bodies. Inasmuch as human beings are compounds of body and soul, there is no such thing as a purely bodily pursuit.

Thomas Jefferson, who thought deeply about the formation of republican citizens, addressed the question of proper exercise in a letter to his fifteen-year-old nephew, Peter Carr. After admonishing him to moral behavior and detailing a course of reading in ancient history, poetry, and philosophy, Jefferson instructed him to spend two hours a day exercising:

Clearly, Jefferson had a number of concerns about exercise. For the body, he recommended moderate (but sustained) exertion rather than violent effort; for the mind, he wanted relaxation and refreshment (secured through the diverting observation of nature); for the character, he preferred vigilant self-reliance rather than conformity to team spirit.

Against Jefferson’s wishes, Americans soon became a ball-playing people. Most of us have exchanged the serious solitude of the streams and forests for the camaraderie and competition of the playing field. Unlike Jefferson, we believe that being part of a team—including rooting for a team—can be good for us. Parents hope that their children will be healthy and fit, develop specific athletic skills, and perhaps acquire beauty of form and movement. Beyond physical excellences, they hope for character training—all that is implied by words like practice, effort, discipline, and concentration. They hope their kids will learn to be neither a ball hog nor afraid of the ball, neither boaster nor coward. Perhaps they sense the benefit of games—which are highly rule-bound, man-made constructions—as a preparation for self-government, where one lives as a citizen under laws that the community has given itself. Perhaps they hope that being part of a team will allow children to experience the subordination of the self to a larger whole engaged in a noble endeavor.

Granting that a wide variety of sports can help inculcate virtues of body and soul, we still ought to ask, are some better at it than others? Are there qualities of character that belong especially, perhaps even uniquely, to some sports? Moreover, do the virtues cultivated by a sport have any political valence? Baseball was once overwhelmingly the national pastime. Was that purely accidental, or was there a connection between the national game and the national character?

Does it matter that so many American youngsters now play soccer rather than baseball? Jefferson’s opinion that ball games “stamp no character on the mind” may well be accurate with respect to soccer. The virtue-neutral aspect of soccer is consistent with its universal appeal. Soccer is played in all manner of regimes, from the radically secular to the theocratic, from dictatorships to democracies. Soccer is never psychologically demanding or politically formative in the way that baseball is.

For a beginning player, baseball involves long stretches of boredom interrupted by moments of heart-stopping terror. The punctuated pace of baseball requires the development of coiled attentiveness (it is estimated that Cal Ripken assumed the “ready position” twenty-one thousand times a season) and unflappable self-control. There is no flow as in basketball or soccer. Flow can hide a multitude of mistakes. In baseball, each moment is distinct and features one individual. (John Updike famously dubbed baseball “an essentially lonely game.”) The whole team is counting on that player in that moment. The possibility of utter humiliation does not disappear even at the professional level—think of Bill Buckner’s fielding error in the 1986 World Series.

Of course, there are key moments in other games: you get the ball in the final seconds and must score. But often those moments can be scripted or engineered; a coach goes to the player he thinks can deliver. In baseball, however, the offense is fixed from the start by the batting order. It’s your turn and no one else’s. Although there are strategies involved in setting the batting order, there is also an inescapable element of chance in how the order plays out in any particular game. It is a lottery—and lottery is the quintessential democratic mode. The assumption behind the batting order is that each individual deserves an equal chance. There is no taking turns in other ball sports. Kids will naturally feed the ball to the best players or their friends; in other words, they adopt either the aristocratic or the oligarchic principle. Baseball’s batting order is salutary in that it insists upon and demonstrates just how difficult democracy is. Especially at the younger levels where natural inequalities are more pronounced, stronger hitters must learn to cheer on their teammates and weaker hitters must learn to conquer dread, learn to draw the walk, learn to bunt, learn even to “take one for the team.”

Just as everyone bats, so too everyone takes the field. A baseball team is like a citizen militia rather than a professional military with distinct ranks and services. There is no division into fully separate offensive and defensive squads as in football; there is nothing remotely like a quarterback, barking orders. The array of skills—batting, throwing, catching, running the bases—that must be mastered by each player in baseball is truly daunting.

The democratic individualism of baseball is also on display in the shape and dimensions of the field, which allow each player—and each spectator— a sovereign view of the whole. Home plate is a vortex from which radiate foul lines stretching (theoretically) to infinity. These are the respectable distances of self-government, where each action is ideally transparent, seen by all, understood by all. The experience of football is the opposite.

The gridiron illustrates the fog of war. If you are one of the grunts on the front lines, you slam the guy facing you. You know the planned movement as it appeared on the sweeping arcs of the general’s map or the coach’s diagram, but you don’t witness its execution or failure. The perspective of the football player is partial. That’s why teams have to pore over the game films, so they can retroactively figure out what happened.

Of all the major sports, baseball has been most resistant to the inroads of technology, both in equipment (contrast baseball’s preservation of the wooden bat with the game-changing evolution of tennis rackets) and in the use of the instant replay, which seeks to replace fallible human judgment with scientific accuracy. Baseball was the last major sport to allow a role for such technology, and it has kept that role strictly limited. In general, the status of the umpire—especially the home-plate umpire—is different from the referees of other sports, who mostly police infractions and dole out occasional penalties. Referees are like the policemen that every regime must have, but the home-plate umpire is more like the independent judiciary unique to liberal democracies. In baseball, every pitch requires a judgment call. What the umpire does differs in both degree (the frequency of his calls) and kind (calling balls and strikes is qualitatively different from calling violations like offside or traveling). The umpire is integral to the game to an unparalleled degree. Not surprisingly, umps come in for more abuse from players, managers, and fans than do refs.

Once again, the situation in baseball can be analogized to our political life. In the American republic, the attitude toward the law is complicated. Law-abidingness is a virtue, and a duty since you have consented to play by these rules. At the same time, standing up for your rights, speaking truth to power, and resisting bad government are admired. Justice is not reducible to obeying the law. Baseball embodies this duality. It encourages deference to judicial authority by enshrining judgment behind the plate (the rules forbid players to dispute calls); but it also, by the unwritten rules, tolerates a fair bit of raucous questioning of authority. Baseball doesn’t permit civil disobedience (no game could—and it’s a serious question whether any polity should), but it does put up with obedient incivility. Hurling invective at umpires readies one for bad Supreme Court decisions.

One thing an umpire does not control is the clock. There is no clock in baseball. By contrast, games played within the bounds of large rectangles— basketball, soccer, hockey, football, lacrosse—usually play by the clock. Moreover, there are no ties in baseball and no quick, sudden-death mechanism to resolve a tie. You just keep playing. Games played on the clock suit the hectic pace of modern life: dash to the game where the kids dash around for an hour then dash to the next lesson or appointment. Baseball, though, insists upon its own internal rhythm; innings are infinitely variable (a side might bat around or it might be three up, three down). Fascinatingly, one of the dictionary definitions for inning is “an opportunity for action or accomplishment.” Whereas a quarter is a fixed increment, an inning is shaped by the action itself. An inning is a timeless, alternate world of human agency.

Other evidence of the unbounded character of human aspiration in baseball is that the foul lines are not absolute. In rectangular games, outof- bounds means out-of-bounds. Nothing of significance occurs there. In baseball, by contrast, foul balls on the fly are playable. Fielders are encouraged to make stunning catches in foul territory. The same lofty ambition is possible for batters. The home run goes beyond the dimensions of the outfield, sailing over the wall and even out of the stadium altogether. Thus, baseball rewards achievements that technically transcend the horizon of the game. In no other sport can you score outside the lines.

Perhaps because the pace is slower (in what other sport is a special break, the seventh-inning stretch, provided just for the spectators?), it is sometimes asserted that baseball belongs to pastoral America. The self-contained, world-unto-itself character of baseball is often described as “leisurely.” Among the Greeks, the proper use of leisure was worthy activities—among them politics, prayer, philosophy, and play—engaged in for their own sakes. Real leisure takes one out of time and self. Baseball’s exemption from the clock encourages this salutary forgetfulness. It is old-fashioned in the sense that freedom is understood and experienced not as license but as transcendence. It’s no wonder that baseball—along with religion and philosophy— is endangered in our profoundly this-worldly, uncontemplative time.

Because the object in baseball is not to put the ball in one fixed place (the basket, the goal, the end zone) but to get players “on base” and then “home,” there are unique possibilities for team play. Most revealingly, in these other ball sports there is nothing equivalent to a sacrifice fly or sacrifice bunt, where an out can advance the runner. Of course, there is teamwork in all team sports, and young people gradually learn the value of making the pass that leads to the shot on goal. A sacrifice fly, however, conveys deeper lessons about the subordination of self than an assist does. The cooperative virtues taught by baseball are of a higher order.

Sports are often analogized to warfare. Football may teach the martial virtues of pain and discipline, but a baseball player might be more likely, upon an instant, to take the individual initiative to fall on a grenade for the sake of his buddies, so they can return home. Moreover, the baseball diamond teaches the priority of home. Baseball knows that war, though both necessary and ennobling, is for the sake of peace. The offense in baseball is nonimperialistic in character. There is no unseemly gloating at home plate as there is in the end zone of the enemy.

MEMORY AND HISTORY

Because baseball is a game of statistics, it is a game of records and the record book. Just check out the Baseball Records Committee of the Society for American Baseball Research, for whom records are made not to be broken but to be discovered, cataloged, corrected, and analyzed. Baseball records reach back into the distant past. My son, who plays soccer and baseball with equal devotion, can still name only one famous soccer player from the past (Pelé). By contrast, he has heard the names of scores of old-time baseball players, has a handful of their cards, and has read books about legendary figures who died well before he was born. Baseball lengthens memory.

By encouraging reverence, baseball goes against the dangerous democratic tendency to forget the past and celebrate the new. Democracy is precarious because it so often undercuts its own moral underpinnings. Paradoxically or not, it turns out that conservative virtues are needed to sustain the democratic experiment. Baseball shows the way: it has a constitutional soul that secures the future by preserving the past. If there has been anything positive about the steroid scandal in baseball, it is the talk of asterisks in the record books. This is an example of constitutional vigilance, protecting the game’s structural integrity and fidelity to history.

There is a related discipline for which baseball constitutes a preparation: the art of storytelling. From the point of view of the spectator, many of the superiorities of the game culminate in the uniqueness of baseball’s scorekeeping. No other sport offers the same level of participation to its fans. Scorekeeping is a form of translation; the action is translated into symbols, which can then be translated into a narrative. What better preparation for a life of scholarship than to learn that exciting stories can be lodged in, and then extracted from, curious markings? A child introduced to scorekeeping is primed to greet documents and texts of all kinds— whether natural or man-made—with enthusiasm. From the fossil record to voting records, from the songs of grasshoppers to the dialogues of Plato, there are esoteric meanings and truths to be puzzled out.

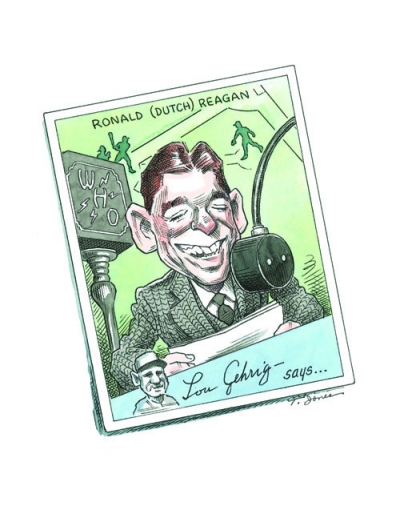

My dad taught me to keep score. While my parents worked in the yard, gardening and building stone terraces, I sat at the picnic table taking down the Twins game from the radio. Because of its narrative quality, baseball is especially suited to radio. Political pundits often mention Ronald Reagan’s career as an actor (usually with a discreditable implication), but his years as a radio sportscaster may have been more important for the development of his skills as a political orator.

Baseball and language belong together. American speech is rife with baseball idioms, as a glance through The Dickson Baseball Dictionary will reveal. Wordsmiths have always been drawn to baseball: from the vernacular (the specialty of players like Dizzy Dean, Satchel Paige, Casey Stengel, and Yogi Berra) to belles lettres, memorable language has surrounded the baseball diamond. That the national game should be so word-drenched could hardly be more appropriate, for the United States is a nation founded by and upon words, from the bold pronouncements of the Declaration to the written Constitution (the world’s first). We are a nation with a narrative.

A NEW BIRTH OF FREEDOM

Narratives of course have beginnings, middles, and ends. Here the baseball metaphor perhaps breaks down, for although both individual games and seasons end in either victory or loss, baseball renews itself each year. Not so with governments. So far as we know, all political orders perish. But here again, baseball speaks in a salutary way to our hope that “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” Baseball is a game of surprises, extra innings, and, should all else fail, the promise of spring. Baseball is a hopeful game.

It is sobering to realize that the perpetuation of our polity has certain moral preconditions—preconditions that may be in danger of eroding. So too the perpetuation of our national pastime depends on certain qualities of character in both players and spectators. However, it turns out that both sets of requisite virtues may be prompted by the very activity of playing ball. Happy thought: “Play ball!” could become the rallying cry of American moral and civic renewal. Whereas Thomas Jefferson counseled against ball games, Abraham Lincoln had a baseball diamond built behind the White House and often joined his sons and their friends in playing ball—testimony to the homely wisdom of Father Abraham.