- History

- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

Editor’s note: This essay is an excerpt from Angelo Codevillo’s new book, To Make and Keep Peace Among Ourselves and with All Nations (Hoover Press).

“. . . peace among ourselves and with all nations . . . ”

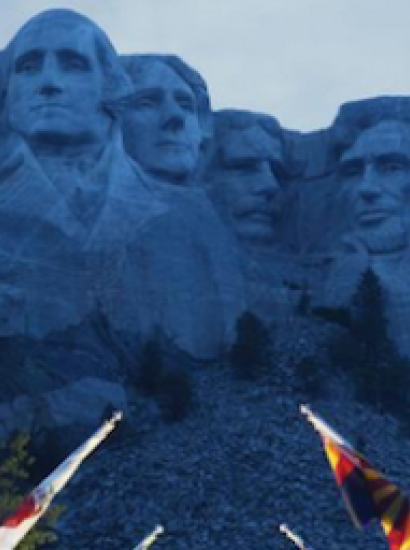

By these final words carved in his memorial, Abraham Lincoln underlined the belief of America’s founders that securing peace is our Union’s primordial job. Knowing that foreign wars and strife among fellow citizens exacerbate and lead from one to the other, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay devoted the Federalist Papers’ first section to peace. In our time, American statesmen seem to have forgotten. I aim to recall the simple truth that “peace among ourselves and with all nations” is statesmanship’s first goal, and hence that its chief question must be: “What is to be our peace?”

Photo credit: Hoover Press

As St. Augustine wrote in the fifth century AD, even pirates crave peace among themselves if only to enjoy their plunder. But they find it difficult to keep peace with one another because they are habituated to making war on mankind. All know that nations are born and die as a result of international battles won and lost. Less noticed but equally true is that any nation defines its character, determines the extent to which it may enjoy internal peace and liberty, by how it deals with matters of war and peace.

Throughout the ages thoughtful persons have noted that while peace among nations does not guarantee peace within each nation, peoples at war with one another do tend to suffer strife among themselves, and that loss of liberty often results even from wars that end in victory. Wars lost or simply long continued produce these tragedies as a matter of course. History teaches us how difficult to gain and easy to lose are domestic harmony and liberty, as well as how dependent they are on peace among nations. In short, peace with “all nations” is a necessary (alas, not a sufficient) condition of “peace among ourselves.”

What I lay out in my book is a history of the ideas concerning the relationship between domestic and international peace that have prevailed in our civilization and especially in our country. This summary of history begins in the Greco-Roman era but moves through time unevenly, slowing down as it approaches our own century, to focus attention on the problems of peace closest to us: Why is our America not at peace, its domestic liberty now in danger? What should be our America’s peace? What can it be, given our circumstances? How did America’s statesmen lose the founding generation’s priority for peace? How did they lose sight of the principle that the prospect of peace must rule the conduct of war? How did they come to confuse the very distinction between war and peace, imagining that the American people can live indefinitely without peace?

How did our national-security state arise? What can we expect from it?

Peace and Civilization in the West

Thucydides’s history of the Peloponnesian War is written as a tragedy: As the Greek cities of the fifth century BC fought one another, they undermined civilization within themselves. Thucydides begins with an account of how Greek civilization was born out of the legendary king Minos’s establishment of peace in the Aegean world, describes its flowering, and then contrasts the wonders of Periclean Athens born of peace with the hell-on-earth of the revolution that resulted from war throughout Greece. For two and a half millennia, that history had cautioned readers.

America’s founders took particular note of how the Athenian people had thrown away their precious democracy under the lash of war. The founders also looked upon Rome’s greatness as tragedy of a different sort. Rome, history’s greatest winner of wars, had shown that when human qualities such as valor, virtue, inventiveness, and dedication, admirable though they be, are used to dominate foreigners they produce all-consuming strife and oppression at home.

Christianity had biased medieval civilization’s mind toward peace. Jesus’s distinction of duties to God and to Caesar, as well as His dedication of mankind to a kingdom “not of this world,” taught classical civilization’s Christian heirs that spiritual concerns take precedence over worldly ones. The Hebrew Bible’s account of God as Father of all mankind gave Christians further reason to resist lending themselves to war, and fit well with Greek philosophy’s discovery of a single human nature naturally ordained to intellection. The cause of peace also benefited politically from the fact that the Germanic tribes who inherited temporal power over Roman lands limited each other’s pretensions by guarding their individual independence. But translating preference for peace into practice has been the ever-difficult work of millennia.

Christians assert that since government exists to serve the people’s secular interest, the primordial of which is peace, war can only be a means to establish peace or an extraordinary counter to threats to peace. Moreover, because peace is everybody’s interest, war cannot be merely the business of sovereigns.

Sovereignty itself is problematic for Christians. Saints Augustine and Aquinas, having distinguished power from truth, warned that claiming sovereignty over both violates man’s divinely ordained nature, and hazards peace as well. Nevertheless, Europe’s kings and clergy indulged humanity’s innate thirst for all manner of power and deference. Only gradually did Christianity’s ethos of peace and freedom become part of Western statesmanship—first and partially in England, then to flower in America’s English colonies.

In England, the imported Germanic feudal tradition was responsible at least as much as Christian theology for lords’ and then for commons’ imposition of the Magna Carta of 1215, and then of financial restrictions on kings’ power to make war. The ensuing complexity of the English regime’s roots underlined the appropriateness of Sir John Fortescue’s fifteenth-century description of it as dominium politicum et regale, in which king and country must collaborate for the common good. Attachment to this medieval vision animated resistance to the royal absolutism of the fifteenth through eighteenth centuries. The resisters’ party, called Whigs, was the trunk out of which America’s English revolutionaries branched.

We see the Whig trunk’s character most clearly in the writings of Henry St. John Viscount Bolingbroke—a Tory—who, in the early eighteenth century, defined the “loyal opposition” to the king’s court by what he called “the country party.” Bolingbroke wrote against Machiavelli’s exclusion of natural right from public life, and in opposition to unnecessary war. Machiavelli had eclipsed the distinction between right and wrong by assuming the normalcy of war. Bolingbroke was neither the first nor last to note that war empowers royal absolutism.

America, Founded for Peace

America’s settlers had not crossed the Atlantic to fight battles of their own, much less the king’s. The New England colonies took enthusiastic part in war against France’s Quebec primarily to secure their frontier against the horrific Indian raids that the French were sponsoring. But by the mid-eighteenth century the British habit of trying to command colonial militias for imperial priorities rather than for domestic peacekeeping had worn thin the colonists’ loyalties. After the French and Indian War of 1763 had ended these raids, participation in the British Empire became synonymous to Americans with domestic oppression.

Thenceforth, the Americans’ supreme request of British authorities was to be left in peace. In 1774 Thomas Jefferson, echoing countless preachers and local authorities, described the “rights of British America” in terms of the people’s natural right to have, to hold, and to dispose of lives and property, a right that comes from God and hard work (cf. John Locke) rather than from any potentate. The Americans of 1776–83 fought to be equals among the nations of the earth, from which they hoped only mutual forbearance.

Historically literate and conscious that their physically enormous country and fast-growing population guaranteed some kind of greatness, the Americans rejected Rome’s kind of greatness because Rome’s conquests abroad had produced bloody corruption and despotism at home. Americans, who were eager to show the stars and stripes “at Canton, in the Indus and Ganges,” also tried to limit their international intercourse to commercial reciprocity—vide John Adams’s unsuccessful 1776 design of a purely commercial “model” for future treaties.

But the Revolutionary War reminded the founding generation of statesmanship’s timeless fundamental: si vis pacem para bellum. If you want peace, ready yourself for war. Thus Alexander Hamilton and James Madison condensed the lessons of international reality into George Washington’s 1796 Farewell Address: “Observe good faith and justice towards all nations; cultivate peace and harmony with all.” From that followed Washington’s “great rule”: “in extending our commercial relations to have with them as little political connection as possible . . . even our Commercial policy should hold an equal and impartial hand: neither seeking nor granting exclusive favours or preferences; consulting the natural course of things; diffusing & deversifying by gentle means the streams of Commerce, but forcing nothing.”1

Americans might enter into offensive or defensive alliances in extraordinary circumstances, such as the Revolution. But ordinarily, said Washington, Americans ought to refrain from espousing or opposing foreign causes. Rather, they ought to build the power to pursue their own.

Washington was emphatic about this because the mere possibility of American involvement in the wars of the French Revolution had come close to ripping apart the young nation’s body politic. These conflicts would lead the administration of President John Adams to try forcibly securing domestic peace by that era’s version of “homeland security”—the 1798 Alien and Sedition Acts. But that historically literate generation remembered that the inherent futility of such measures was well known even to Machiavelli. Domestic strife subsided only two years later, when Adams’s combination of naval power and diplomacy ended America’s “quasi-war” with France.

The sixteen years of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison’s presidencies were plagued and well-nigh defined by inability to deal with foreign war’s powerfully divisive influence at home. Both presidents tried to keep out of the Napoleonic wars by balancing increasingly warring factions at home, and by mere economic sanctions abroad. But, they ended up having to fight the War of 1812—a war as disastrous at home as it was abroad—because they had stopped building the navy that Washington and Adams had started, and unarmed diplomacy proved impotent to diminish British and French pressure on America. New England almost seceded from the Union, the British Army burned Washington, DC, and Britain’s Indian allies massacred the first settlement of Chicago.