- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- US

- Contemporary

- Military

- World

- Security & Defense

- US Defense

- Terrorism

- History

Looking back on the two decades since the tumbling of the Berlin Wall, what have we learned? Can reflection prepare us for the future? A brief review will help clarify our thinking just in time for the start of a new presidential administration.

THE COLD WAR: GOOD OLD DAYS?

America’s rise to solo superpower status came about with the Soviet Union’s collapse and disintegration. With the vanishing of its Cold War nemesis, the United States bestrode the globe not as a militaristic empire but as the sole standing superpower after a four-decade confrontation. Rather than hankering after fresh conquests or overseas colonies, the American people looked briefly inward, away from international burdens and toward a “peace dividend” after decades of heavy defense spending, while their governments heedlessly slashed the standing military forces by 40 percent during the 1990s. This was to be the era of the United Nations, “robust multilateralism” in foreign affairs, and globalization.

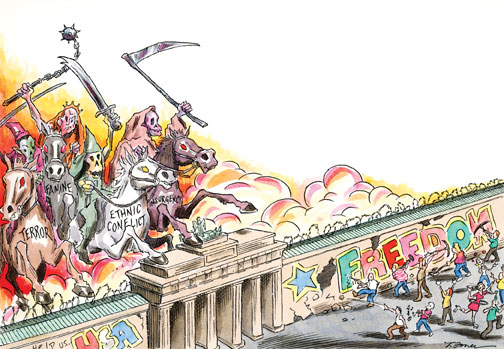

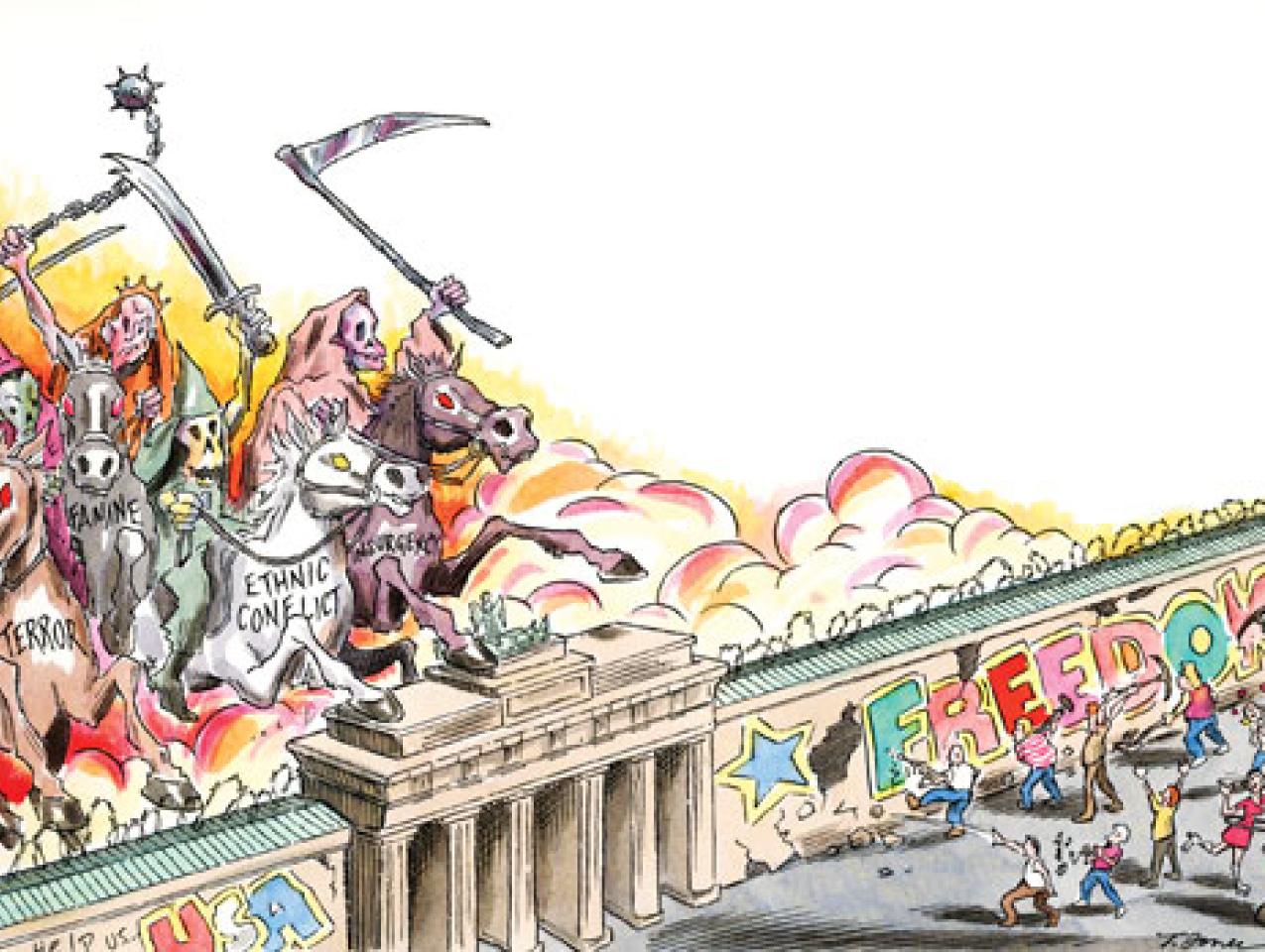

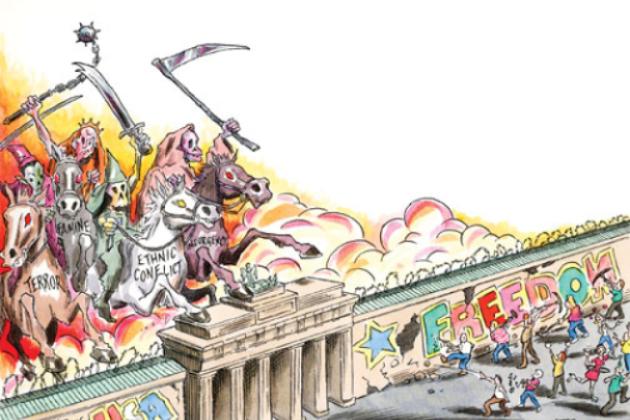

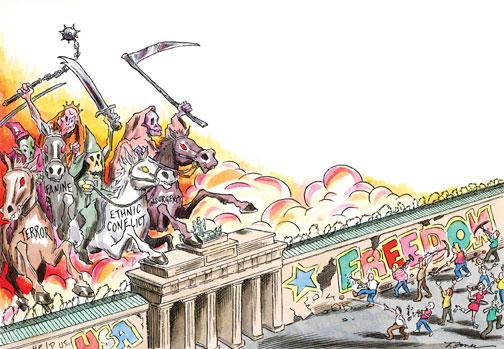

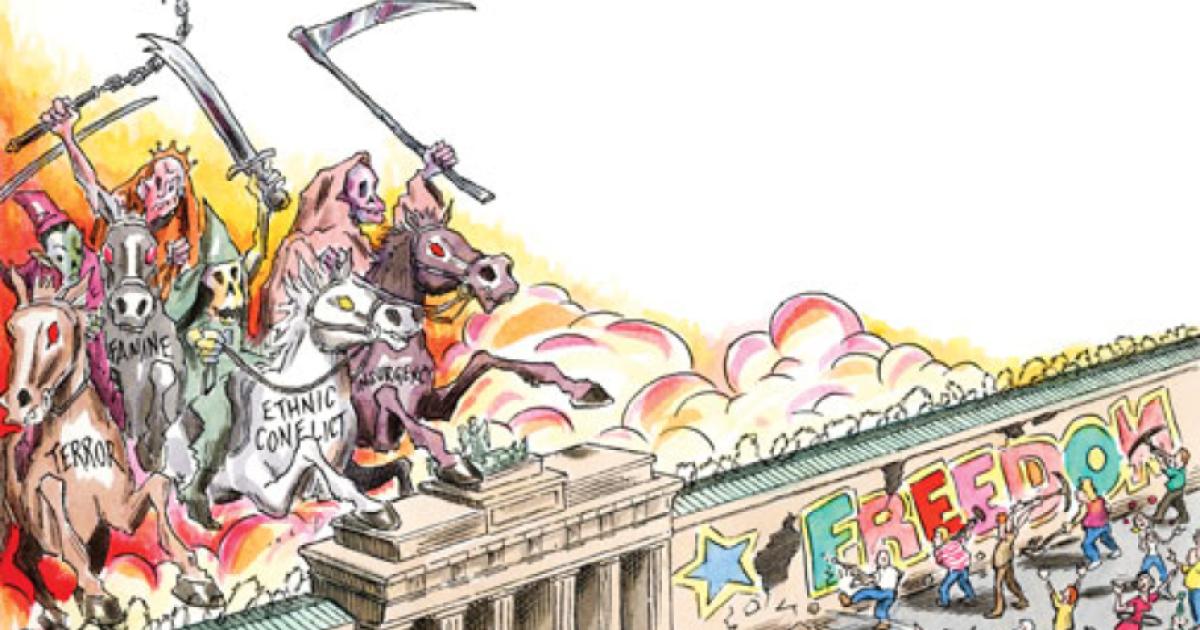

Instead of peace, tranquillity, and ubiquitous brotherhood after the Berlin Wall tumbled, the world pitched into turbulence. Malevolent forces broke loose from the bipolar constraints imposed by Washington and Moscow to limit conflicts that might escalate into a nuclear war. Sure enough, the freedom, democracy, and independence that leaped across central European countries that had been held in the Red Army’s iron fist since World War II gladdened hearts in the West. But the Wall’s fall, German unification, and withdrawal of Soviet tanks also meant trouble into the Atlantic alliance. The political glue that bound Western Europe and the United States into a bulwark against Soviet expansionism dissolved with the Wall. Europe no longer depended for security on its alliance partner across the Atlantic; it was free to drift from ally to critic.

Outside the core of the Western world, things went from bad to worse after the Soviet Union’s demise. Rather than closing the lid on a Pandora’s Box of ethnic conflict, war, insurgency, humanitarian tragedies, and terrorism, the Wall’s crumbling seemed to fling the box open and empty its malign contents onto the unsuspecting United States.

The spate of crises even evoked a whiff of nostalgia for the Cold War’s good old days of stability and predictability, as the post-Wall world called for the application of more U.S. power than during the constrained East- West competition.

CHAIN LINKS—ONE CRISIS AFTER ANOTHER

As the dust settled from the falling stone slabs that had partitioned Berlin, Americans peered at a much less tidy international landscape. The new world disorder coughed up warlords, tinhorn dictators, freelance terrorists, and simple thugs whose atrocities brought wanton violence, mass death to demonized tribal or religious outsiders, “blood diamonds,” and raw political power. To stabilize—and sometimes to democratize—chaotic lands, the United States embarked on a series of interventions that have characterized American foreign policy since 1989.

Two months after the Berlin Wall collapsed, the George H. W. Bush administration intervened in Panama to overthrow Manuel Noriega rather than turn over administration of the Canal Zone to his tender mercies. The ham-handed and brutal Noriega was the first in a line of dictators to be confronted by Washington.

Next the Bush White House collided with a far more ominous threat: Saddam Hussein’s ruthless conquest of tiny Kuwait in August 1990, which posed an additional danger to the world’s largest oil prize—Saudi Arabia. President Bush obtained the blessing of the United Nations and troop commitments from around the world, including Middle Eastern countries, to expel the Iraqi occupiers. The Persian Gulf War saw a buildup of 500,000 U.S. soldiers, together with an allied force of 160,000 from thirty-four countries. After a thirty-nine-day aerial bombardment, Operation Desert Storm resulted in a lopsided coalition victory in less than a hundred hours of ground fighting. But the political outcome did not match the spectacular information-age weaponry and decisive military defeat of Iraq, with Washington merely expelling the Iraqi attackers from Kuwait and accepting the retention of power by Saddam Hussein.

The result was an armed hiatus, not a genuine peace. The Baghdad dictator soon provoked the international community with bluster, support for terrorism, and the threat of a buildup in weapons of mass destruction. In response, during the next decade, the United States patrolled no-fly zones in the north and south of Iraq, backed U.N. arms inspections, and even bombed Iraqi military targets from time to time.

The Bush White House next acted on humanitarian impulses by feeding the destitute in the failed state of Somalia. The Clinton administration then set about nation-building in the anarchic Horn of Africa by deploying elite U.S. Army troops to capture the infamous clan warlord Mohamed Aidid. That hunt led to the bloody incident of October 3, 1992, when Aidid’s militia shot down two helicopters deployed to capture his henchmen. The ensuing fifteen-hour urban battle cost the lives of eighteen U.S. Army Rangers and Delta Force troops and some five hundred Somalis. Americans at home were horrified by television images of their soldiers’ bodies being scourged and dragged through the dusty streets, having believed that the United States was engaged in a strictly humanitarian mission in Somalia. The Oval Office soon beat a hasty retreat, and by March 1993 the bulk of U.S. troops had left. Somalia sank back into anarchy.

The ill-fated Somalia intervention led to two consequential outcomes. First, the Arab world, and particularly Osama bin Laden, took note of the world’s superpower turning tail and retreating after suffering casualties without retribution. The Saudi exile-turned-terrorist proclaimed in a 1998 fatwa that America left Somalia “in disappointment, humiliation, and defeat.” He added that U.S. “impotence and weakness became very clear,” and he resolved to test Washington with a series of terrorist attacks.

The second, and no less consequential, result was the constraint placed on U.S. power. The Mogadishu casualties and the public’s distaste for military escapades dampened President Clinton’s enthusiasm for militarized intercessions no matter how excruciating the plight of foreign populations. The Oval Office, for example, turned its back on the Rwanda genocide that would cost an estimated 800,000 lives. It also wrung its hands over restoring the legally elected, but junta-ousted, Haitian president for more than a year, lest the operation degenerate into “another Somalia.” Squeezed by the approaching midterm 1994 congressional elections and racially tinged lobbying from the Democratic Black Caucus, Clinton tiptoed up to Operation Uphold Democracy, which restored Jean-Bertrand Aristide in the presidential palace for ten years, until the presidency of George W. Bush removed him from power.

Even in the face of mass murder and ethnic cleansing during a three-year period in the Bosnian crisis, the Clinton White House procrastinated and dragged its feet. Senator Bob Dole’s candidacy and the approaching 1996 presidential election at last galvanized the Oval Office into action that eventually saw NATO peacekeepers march into Bosnia, ending a humanitarian tragedy and an international crisis.

Four years later and still in the Balkans, the Somali incubus haunted Clinton and his top aides. Here again, a Muslim population in the breakaway province of Kosovo beckoned for Western rescue. Mutual cruelties inflicted by Serbs and Muslims on each other reawakened the West’s conscience about mass murder and hardship. Fearful of land warfare, Washington prevailed on its NATO allies to launch an air campaign against Serbia. After nearly three months of bombing, Belgrade refused to budge in its claim to Kosovo. But after the Clinton administration put a land invasion back on the table, Serbian strongman Slobodan Milosevic finally capitulated to a NATO-protected Kosovo.

The same risk-averse mentality marked America’s response to the rising level of Islamist terrorism in the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Centers, the 1998 East African embassy explosions, and the 2000 attack against the USS Cole in Aden’s harbor. Not until the 9/11 attacks did the United States take seriously the mounting terrorist peril. Then it struck back.

In some ways, the Bush administration’s exuberant use of military power in Afghanistan and Iraq was a correction to a wide pendulum swing away from the unsheathed sword. Likewise, the Bush White House’s initial coolness to stability operations and nation-building also stemmed, in part, from its perceptions about its predecessor’s inclinations to wade into places like Somalia, Bosnia, Haiti, and Kosovo for mainly humanitarian impulses.

HAVE WE LEARNED ANYTHING?

After the first Bush administration launched its near-perfect armed operation to topple Manuel Noriega in late 1989, Panamanian crowds took to the streets, looting and trashing the capital’s business district. Washington was compelled to deploy more troops to deal with the postinvasion civic disorder than to launch the initial assault.

Once NATO ground forces swept into Bosnia after the Dayton Accords were signed in 1995, they encountered another unanticipated postconflict imbroglio. Unprepared for civil disorder, NATO soldiers stood aside while Serbs burnt down their own houses in Sarajevo rather than turn them over to their hated Muslim neighbors.

A few years later, when NATO intervened to rescue a Muslim population in Kosovo, it again did so without enough military power. Reluctant to employ ground forces in its second Balkan clash, NATO relied solely on air power.

In the assault on Afghanistan for its sheltering of Al-Qaeda, the initial campaign went brilliantly. Less than three weeks after 9/11, the Bush administration commenced bombing the mountainous country. Small numbers of special-operations forces and CIA operatives organized and coordinated anti-Taliban militias. A combination of American precision bombing and U.S.-backed Northern Alliance forces, which had long fought against the Taliban regime, routed Al-Qaeda and its Afghan backers. But the lull that followed the opening attack witnessed a lapse in American planning for an endgame; the coming war in Iraq diverted attention, troops, and money from securing the peace in the long-embattled Central Asian country. By 2005, the Taliban, entering from neighboring Pakistan, staged a revival inside Afghanistan. Helped by Al-Qaeda, the Taliban and other anti-American tribal chieftains initiated suicide bombings, roadside explosions, and ambushes against NATO soldiers.

Thus, U.S. lack of preparation for a breakdown in law and order in the days after the fall of Baghdad in 2003 fits into the context of other post–Berlin Wall engagements. In the case of Iraq, early missteps unraveled the astounding U.S. military victory, resulting in a rapid progression from street violence to a multisided ethnic insurgency. The main causes—inadequate troops for constabulary duties, disbanding the Iraqi army, unwillingness to employ Iraqi officials in post-Saddam Iraq, and hesitant counterinsurgency practices—are well-recorded missteps.

What is the proper balance between tanks and food trucks?

THE PAST AS PROLOGUE

The new presidential administration will no doubt reflect on the lessons of the twenty years that followed the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Military power must remain an option to combat terrorism and contain nuclear-ambitious states like Iran. But military power alone will not suffice against terrorism, ensure U.S. security, or promote democratic values. Already, counterterrorism is under way in the Philippines and the Horn of Africa, conducted by specially trained troops who not only teach the locals to fight terrorists but improve the lives of villagers with roads, wells, jobs, and medical clinics. These clandestine, small-footprint operations are preferred over massive occupations that alienate populations.

America’s multiyear wars in Afghanistan and Iraq may serve as a watershed: a time that divides an era of interventions from a period of nonintervention. But that outcome is unlikely. Instead, the United States may become less willing to intervene overseas, doing so only with allies or with the blessing of the United Nations.

If past trends can be taken as predictors of future actions, the new U.S. government must do a better job of envisioning outcomes of interventions, meshing ends and means, and securing military victories with civic stability. The failure to plan for postliberation realities is a recent phenomenon.

By late 1943, for example, the United States had already embarked on planning for Nazi Germany’s postdefeat governance, an American way of war that offers lessons for us today.

Policy makers must draw conclusions from what has happened during the past two decades. Military planners need to study closely the postconflict environment in Iraq for lessons on how to handle future problems and the best means with which to tackle them. In this way, the future remembers the past and the present cannot escape history’s influence. The historical stretch from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the Iraq War will weigh heavy on the United States for the foreseeable future as it confronts international terrorism, Iran’s nuclear and regional ambitions, China’s reach for a global place, and a newly resurgent Russia. America’s unipolar moment, despite its exertions in Iraq, is not finished. Looking clearly at our recent past offers us lessons, both positive and negative, with which to forge ahead.