- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

Most people, most of the time, lead lives removed from political and ideological engagement. Family, work, health, sports, and entertainment define what is generally held to be a normal life.

It is also in our national DNA to believe that we are entitled—indeed, obligated—to have a loud voice in the conduct of our government. Isn’t that what our Founding Fathers, and our American ethos, require? Yet we vote at a measurably lower rate than the citizens of most other democracies (although, as their lives improve, they tend to emulate us in this regard). Nor do we generally define ourselves, like most of our counterparts elsewhere, as belonging to the political Left or Right. Indeed, even our traditional Democratic-Republican identities are eroding. A growing plurality of Americans finds comfort in the Independent/non-partisan label.

In sum, we have convinced ourselves that in theory we are engaged citizens, while in fact most of us are the self-family-sports-media-obsessed folk that polling tells us we are. But not all of us, all the time. A substantial number of Americans claim some identity with regard to public life. A fifth of us are ready to say we are liberals; close to twice as many identify themselves as conservatives.

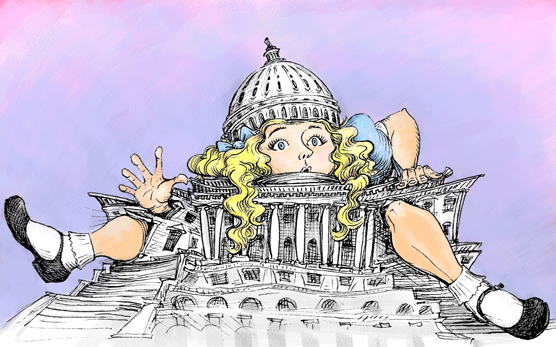

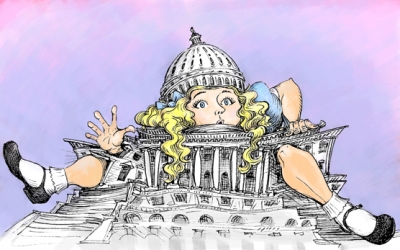

Illustration by Barbara Kelley

There is as well a political class that has career self-interests, or a cultural (or psychological) inclination to be steadily engaged in public affairs. Many are drawn by self-interest and by the sheer excitement of the political game. Others enjoy the ample outlet for commitment to causes that politics, as compared to much of the rest of contemporary society, provides.

The bulk of the political class operates much of the time within the confines of what most Americans would regard as the everyday world. True, partisan discord can grow heated. Yet vigorous interparty thumping is as old as our country, and traditionally has been regarded as a sign of the well-being of our democracy. But the belief that ours is an age of unprecedented polarization is widespread. The usual trope is to see it as a distinguishing feature of the opposition: The terrorist Tea Partyers! The socialist Obamaites!

Are we in fact living in an age of untypical ill-feeling? Compared to more placid times like the 1820s, the 1920s, and the 1950s, perhaps. Compared to notably non-placid times like the 1790s, the 1850s, or the 1960s, no.

What does distinguish ours from past periods is the vastly expanded scale and presence of ancillary political players in public life, beyond the traditional political parties and professional politicians. This includes the media, advocacy groups, the blogosphere, and ideologues for whom the cause trumps the party. These are voices and interests who share an unprecedented volume, ubiquity, and lack of direct involvement in and responsibility for the process and consequences of governing.

The genius of our two-party system has been to modify, or mollify, the more passionate segments of our populace. Do these extra-party players now pose a threat in their expanded volume and their autonomous character? The widely held view is that our on-steroids political culture, with its hyper-ideological polar extremes, does indeed endanger our capacity for self-governance.

That perception has made the political culture an attractive subject for the most conspicuous forms of political analysis: polling, punditry, and prediction. But the character of our current political scene calls for other treatments as well. One is that traditional, but currently out-of-fashion literary device, political allegory. Here is a way not so much of measuring but of testing the view that the current American political scene is in some respects an Adventure in Wonderland.

Some iconic works of Western literature are both political and allegorical. Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726) took its hero to the mythical lands of Liliput and Brobdingnab, whose issues—are high or low heels preferable? do you break an egg at its big or little end?—parody the political world of early Georgian England.

Do we live in an age of unprecedented political polarization?

Voltaire’s Candide (1759) similarly demolished the pretenses, illusions, and hypocrisies of Enlightenment Europe. More recently, George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945) did the same in spades for Stalinist totalitarianism, setting it in the all-too-appropriate locale of a barnyard.

American politics has not inspired much in the way of political satire or allegory: whether that is due to its democratic base, or its generally prosaic character, is hard to say. One exception is L. Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz (1900). It is widely (though not without controversy) regarded as an extended parable of the Populist movement of the 1890s: in itself not your usual American political party. Another notable example of allegory (again, ostensibly a children’s book) is Norton Juster’s The Phantom Tollbooth (1961). But that work is known for its word-play and fantasy more than for a political subtext.

There are two notable works of English literature that lend themselves with special relevance to the task of viewing our current political scene in allegorical terms. These are Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass (1871). Some see cloaked references to imperial mid-Victorian England in these books. But they are regarded primarily as works of exceptional literary imagination. In their inverted, mirror-image way, they satirize human types and social situations. Precisely because they do that, they can also illuminate some of the more patent absurdities of our present political condition.

What do we find in the fantastical worlds of Wonderland and the mirror-image Looking-Glass House through which Alice passes? They are populated with bizarre collections of sorts-of-people and not-quite-right animals, usually speaking in riddles or gibberish. They engage in endless, often nonsensical disputations, mutual threats, and generally antisocial behavior: a not inapt metaphor for our political culture. “It’s really dreadful the way all the creatures argue. It’s enough to drive one crazy!” says Alice, as if she had just emerged from a bout of listening to a panel “discussion” on cable television, or reading what passes for “comments” on the internet.

It is helpful to divide Alice’s Wonderland into two subsets, Rightworld and Leftworld. These are home to the primary political absurdities of our time. Leftworld’s Truthers (35 percent of Democrats, according to one poll), who believe that the Bush administration was complicit in 9/11, and Rightworld’s Birthers (28 percent of Republicans), who believe that Obama is not a native-born citizen, are to the Wonderland manor born.

Al Gore’s list of Inconvenient Truths about climate change is a vintage Wonderland trope. To it may be added the category of Convenient Lies, their convenience depending on your ideology. Thus we have apposite, though quite opposite, renderings in Leftworld and Rightworld of such topics as:

- The Bush administration’s firing of six United States Attorneys. In Leftworld, this was an unprecedented misuse of executive power. In Rightworld, it was an insignificant bleep compared to Clinton’s asking all U.S. Attorneys to submit their resignations.

- The Valerie Plame affair. According to Leftworld, this was the illegal cover-blowing, and thus endangerment, of a CIA agent, orchestrated by Vice President Cheney for political purposes. According to Rightworld, it was the insignificant leakage of a marginal CIA employee not by Cheney but probably by former State Department official Richard Armitage, an event distorted by a Bush-hating media.

- Global warming. In Leftworld, this is a major threat to the world’s well-being, irresponsibly downgraded by anti-scientific conservatives despite its incontrovertible scientific pedigree. In Rightworld, it is the Left’s gross exaggeration for political purposes of a complex and still unsettled matter of scientific investigation.

- Intemperate political behavior. In Leftworld, this consists of near-Fascist Tea Partiers and right-wing Congressmen refusing to do business with a compromise-seeking president. In Rightworld, principled conservatives are slandered by a vengeful media and demonized by a take-no-prisoners, my-way-or-the-highway president.

These and other points of contention are fit for a place in Alice’s Wonderland or Looking-Glass House. One reason for this is that they have a far greater appeal to the chattering, ideological classes, and to the media apparatus that panders to them, than to the general public. In this sense, they resemble the issues that the traditional parties used to stir the passions and secure the support of their ethnic, religious, and regional constituencies.

The difference now is that the ancillary players of our political world—the media, advocacy groups, the blogosphere—are free to obsess on these matters to their hearts’ content, unhindered by the normal political constraints of the clash of differing interests, or the responsibility to legislate and govern. It is this otherworldly dimension that so often makes our public life a political Wonderland.

Sense and nonsense are intimately intertwined in Tea Party discourse.

Another revealing link between Alice’s surreal worlds and our political one is the use of language. Word-play is a defining characteristic in both. When Humpty Dumpty declares in Through the Looking-Glass, “When I use a word, it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less,” surely his is the voice of today’s political class.

Alice, a lonely voice of sanity and common sense in her dream-worlds of insanity and nonsense, quite properly responds: “The question is whether you can make words mean so many different things.” Humpty’s answer is straight out of the modern American political playbook: “The question is which is to be master—that’s all.” (Or in Bill Clinton’s classically Wonderlandish formulation: “It depends on what the meaning of the word ‘is’ is.”)

In a language culture such as this, euphemism flourishes. Our Age of Euphemism fits seamlessly into Alice’s Wonderland. Who among its creatures would find it strange to call the inheritance tax a “death tax,” or government spending an “investment”? Or for illegal immigrants to be called “undocumented workers,” or socialized medicine to be called a “single-payer system”?

Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee refused in 2007 to sign a tornado relief bill because it used the discomfiting phrase “act of God” to describe a natural disaster. Two years later, Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano defended her desire to replace the term “terrorist act” with the more anodyne “man-made disaster.”

Another Wonderland moment: In her spot-on take of Sarah Palin on Saturday Night Live, actress Tina Fey declared that she could see Siberia from her Alaska home. Inexorably, this was attributed to the subject of the satire. Palin actually said, quite accurately, that Russia can be seen from Alaska. But she might have said what Fey said, which in our land, as in Wonderland, trumps the fact that she didn’t.

The bloggers and commenters who populate the ever more surrealistic world of cyberspace eerily echo the more outré denizens of Wonderland. Paul Krugman, who some time ago left the prosaic precinct of mainstream economics to take up full-time residence in Leftworld, recently observed: “If we discovered that space aliens were planning to attack and we needed a massive build up to counter the space alien threat...this slump would be over in eighteen months.” That comment might have readily found a place in the conversational ambit of the Mad Hatter’s Tea Party.

Who can join Alice at that Tea Party without thinking of the current, shadowy “party” that bears the same label today? This is not to deny that much of what the Tea Partiers say, and believe, makes sense in the real world. But as was the case with its predecessors (the Populist party of the 1890s, the Perot movement of the 1990s)—and as was the case in Alice’s Wonderland—sense and nonsense are intimately intertwined in Tea Party discourse. Thus a proper concern for excessive government coexists with excesses such as former Colorado Congressman Tom Tancredo’s observation that “People who could not spell the word vote or say it in English put a committed Socialist ideologue in the White House.”

Much the same can be said of another Alice experience: the Caucus-Race, what she calls a “queer-looking party.” The Caucus-Race attracted a motley crew of characters. It also was circular and pointless, with no clear winner and prizes for all.

Nancy Pelosi is a slam-dunk for the Queen of Hearts.

The current Republican equivalent of the Caucus-Race, the runup to the primaries, will ultimately produce a candidate. But on the way to doing so, it not infrequently echoes its Wonderland forebear. When the Dodo in Wonderland declares that the best way for his pool-drenched fellow-creatures to dry off is to hold a Caucus-Race, the Mouse delivers an historical lecture in order to stupefy his audience, and thus speed along their dehydration. Heavy-lidded viewers of the recurrent candidate debates in the current GOP run-up can readily empathize.

No less surreal, and yet equally applicable to our own time, are the croquet match in Wonderland and what Alice calls the “huge game of chess…being played—all over the world,” which is the leitmotif of Through the Looking-Glass. These contests are disjointed and full of bizarre twists and turns: not inapt metaphors for our gathering electoral battle. Many a winded competitor today can relate to the Red Queen’s admonition to Alice: “Now here, you see, it takes all the running you can do to keep in the same place.”

Along with word-play and bizarre happenings, the Alice books are full of vivid near-people and more-than-animals. Do any of them resemble our current cast of characters?

Nancy Pelosi is a slam-dunk for the Queen of Hearts. “Off with their heads!” indeed. As for the bloodless, querulous King of Hearts: Harry Reid? And as things now stand, the president is ever more like the Cheshire Cat: most of him slowly fading away, leaving only a warm smile behind.

As for the time-obsessed White Rabbit: who among our contemporary public figures fears that he will be too late? Who doesn’t? Timothy Geithner and Ben Bernanke, in hot but fruitless pursuit of that elusive grail, Recovery, are likely prospects. So too are many in the field of Republican hopefuls. At least in the past, Romney has been perhaps the most White Rabbit-like. Some of his rivals are more apt candidates for the role of the Mad Hatter.

The characters of Tweedledee and Tweedledum came to embody the traditional view that the major parties are given over to undifferentiated sound and fury rather than standing for something. But in our hyperbolic political age, we have to account for more impassioned and opinionated voices.

The Leftworld and Rightworld versions of Wonderland are stocked with people who are as opposed to each others’ views as they are similar in their modes of expression. The Tea Party, an entity as difficult to pin down as the Jabberwock, is the most conspicuous instance of this new model of political identity. In a less popular (and populist) sense, a predecessor was the Neoconservative movement (the Neocons), who championed principles of foreign policy much as Tea Partiers do principles of domestic policy.

Leftworld counterparts include entertainment mediacrities like Oliver Stone and Michael Moore, who never met a Communist tyrant they didn’t like. Their whitewashes of Castro and Chavez inject into our political discourse the fantasies of the old Marxist Left: a Neocommunism of sorts. May we call them Neocoms?

In its manifest inequity, erratic procedure, and unclear purpose, the Red Queen’s intermittently conducted trial of an inconsequential figure accused of an indefinite offense is a fine stand-in for many a Congressional hearing or media feeding frenzy. The King’s instruction to a witness (“Give your evidence and don’t be nervous or I’ll have you executed on the spot”) and the trial’s peculiar procedure (“Sentence first—verdict afterwards”) inevitably summon up memories of one or another contemporary mini-drama. When witness Alice concedes to knowing nothing, the King observes that this is important, and orders the jury to write it down. A popular joke from the Clinton-Gore years has the vice president visiting a government agency. He asks one functionary what he is doing; the answer is “nothing.” He asks another one, and gets the same reply. He instructs his secretary to make a note: “There’s a redundancy here.”

Alice’s dream-time in Wonderland ends with her recognition that the characters hectoring her are, in truth, nothing more than a deck of cards. Here we take leave of allegory. Our Wonderland of election-games, of Rightworld and Leftworld, is all too real: indeed, the only political reality we have. But that only adds to the value of observing Alice on her descent into Wonderland, or her journey through the looking-glass into a counter-world in which “things go the other way.” Sometimes looking through a glass, however darkly, illuminates truths not evident in the quotidian light of day.