- Law & Policy

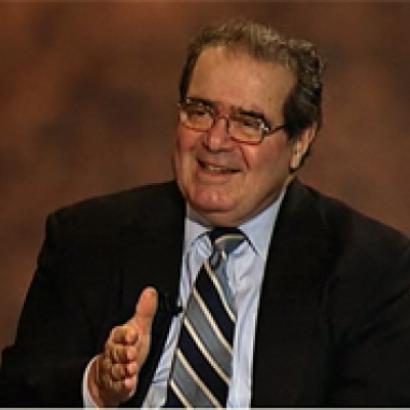

Antonin Scalia, who died Saturday at age 79, was the most influential Supreme Court justice of the past 30 years. Not because he had the votes. He was influential because he had a clear, consistent, persuasive idea of how to interpret the Constitution: It means what it says; it means what those who enacted it meant to enact.

And Justice Scalia was influential because he wrote opinions with verve and good sense, in prose that any American could read and understand. He was the best writer the Supreme Court has ever known—and with justices like John Marshall, Oliver Wendell Holmes and Robert Jackson, that is saying a lot. He was the court’s most withering logician. He showed us what a real judge can be, even on that most political court.

When Justice Scalia arrived at the Supreme Court in 1986, its jurisprudence had become sloppy, results-driven, plagued with fuzzy three-part tests and fuzzier four-part tests, all of them concocted by his predecessors with little basis in constitutional text. Today, the entire court—even the liberal justices—have adopted Justice Scalia’s style: close attention to text, awareness of history, analytical rigor. The Supreme Court has not announced an impressionistic multipart “test” in years.

As a law professor, I find it a joy to teach a Scalia opinion. His opinions make clear their premises. They follow logically. Sometimes students point out that Justice Scalia is not being true to his principles. That is a compliment, because it means he has principles that can be identified and objectively applied. Many justices have no principles for interpreting the Constitution, other than to see in it their own opinions about the issues of the day. Every year, in Constitutional Law, a liberal student will raise his or her hand and say, sheepishly, “I never thought I would say this, but I agree with Scalia.” That is because his highest commitment was to rational deduction from our highest law.

Justice Scalia’s text-and-history approach to constitutional interpretation sounds wonkish. How can the attractions of text and history compare with getting quick national victories on same-sex marriage, affirmative action, abortion, or capital punishment? But text and history are about more than fastidious jurisprudence. They are about democracy: allowing Americans to decide contentious questions for themselves, where the Constitution is, honestly read, silent.

As Justice Scalia wrote in Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), “if in reality our process of constitutional adjudication consists primarily of making value judgments,” instead of “doing essentially lawyers’ work up here—reading text and discerning our society’s traditional understanding of that text,” then the issue is properly one for democratic debate. “The people know that their value judgments are quite as good as those taught in any law school—maybe better.” After all, he wrote, “value judgments should be voted on, . . . not dictated.”

This is fundamental. If constitutional controversies are governed by discernible law, there is a good reason to allow judges to make the decision. That is what judges do: They interpret and apply laws made by the delegates and representatives of the people at some time in the past.

As the great Chief Justice John Marshall wrote in Marbury v. Madison (1802), “It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.” But if constitutional controversies are governed by something other than law, if they are governed by “what the Court calls ‘reasoned judgment,’ which turns out to be nothing but philosophical predilection and moral intuition,” as Justice Scalia put it, there is no reason judges should decide. In other words, it would not be the province or duty of the judicial department to say what the law should be, or to resolve disagreements about philosophy or morality.

Justice Scalia’s political detractors sometimes scoffed that he was merely packaging his own preferences in the trappings of text and history, but any student of the Supreme Court can supply numerous counterexamples. Justice Scalia was undeniably conservative, but he joined with liberals to demand due process for Guantanamo detainees, to protect flag-burning (and cross-burning), to give new teeth to procedural protections for criminal defendants, and to invalidate a law against violent videogames (among many other examples).

He championed the authority of regulatory agencies to interpret their operating statutes, even when Democrats controlled those agencies. He insisted that all executive power must be exercised by a unitary president, even when that president was Bill Clinton or Barack Obama. Bush v. Gore? His detractors forget that the key holding in that case was joined by seven of the nine justices.

True, the results of his text-and-history approach were often conservative. He believed in a colorblind Constitution; he saw no basis in the Constitution for abortion rights; he defended the presence of religion in the public square; he defended the right to keep and bear arms; and he opposed congressional attempts to regulate campaign speech.

On every one of those issues, he offered reasons based on text and history, never on his own philosophy or moral intuitions. He may have been wrong on some of them—I certainly disagreed with more than a few of my former law professor’s constitutional positions—but he reached his interpretations in good faith, as a judge and not as a philosopher-king. He deserves great credit for that.

Justice Scalia’s opinions, especially his dissents, scintillated with wit, blistered with scorn and often soared with appreciation for our constitutional heritage. No one brought more laughter to oral arguments or more trepidation to oral advocates. Sometimes he went too far. But he made his mark. As a result of his three decades on the Supreme Court bench, constitutional law more closely resembles what the Constitution actually says. The American people had their democratic champion. He will be sorely missed.

Mr. McConnell, a law professor and the director of the Constitutional Law Center at Stanford Law School, is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution.