- Economics

- International Affairs

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

After a week in St. Petersburg, I can’t seem to get that old Beatles number out of my head: “I’m back in the USSR / You don’t know how lucky you are.” Russia’s prerevolutionary capital has certainly changed since I was last here in 1990. It has, needless to say, acquired all the garish trimmings of post-perestroika capitalism: billboards for U.S.-style sport-utility vehicles and a rash of neon lights along the Nevsky Prospekt, the city’s Champs Elysées.

And not just the trimmings. Fifteen years ago, the state-run shops lacked even the most basic essentials; people appeared to subsist on air and pickled gherkins. Today there are supermarkets offering a cornucopia of cheeses and chardonnays.

Yet look behind this patina of economic progress and you soon spot disquieting vestiges of the old Soviet Union. Every public building still seems to be guarded by its gimlet-eyed babushka, hell-bent on denying you admission if you do not have five copies of your permit stamped by five different government offices. The Russian bureaucracy may have lost its old air of menace. But it still lurks in dingy, stale-smelling offices, just waiting for the signal to spring back into inaction.

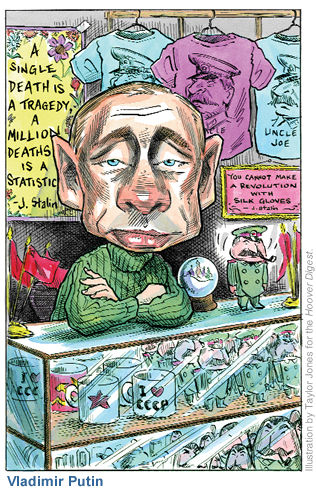

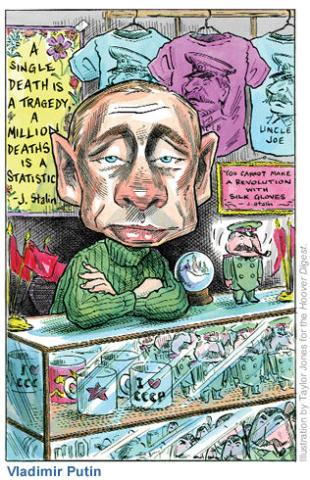

The Russian president, Vladimir Putin, also paid a visit to St. Petersburg recently. This, too, brought back memories of the old days. Whole streets were cordoned off. Motorcades roared around the city, bringing traffic to a standstill. Close to where I was working, a stretch of potholed sidewalk was hastily repaved so that Putin could unveil a plaque there (to the Soviet-era president of Azerbaijan) without stubbing his toe.

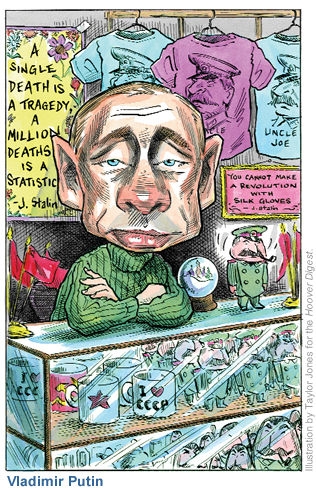

Since coming to power as Boris Yeltsin’s anointed successor, Putin has worked hard to concentrate power in his own hands. His party, United Russia, dominates the Russian parliament. In the aftermath of the disastrous Beslan school siege last September, he took over the appointment of regional governors, who had been directly elected in the 1990s. He has also tightened the Kremlin’s grip on the country’s main television networks.

But Putin’s most dramatic power play has been his decision to break the political power of the business “oligarchs” who were the main beneficiaries of the Yeltsin era. Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the former head of the Yukos oil company, has just been sentenced to nine years in jail for alleged tax evasion and fraud. Everyone here knows, however, that his real crime was to pose a political threat to Putin.

Nobody can deny that all kinds of mischief went on in the Yeltsin years. The privatization of the energy sector was one of the scams of the century, but the vehemence with which Putin heaps opprobrium on the oligarchs awakens unpleasant memories of the old Soviet regime, which specialized in the vilification and destruction of internal enemies.

Even more troubling is Putin’s unapologetic nostalgia for the days when Russia ran the affairs of nearly all its immediate neighbors. “We should acknowledge,” he recently declared in an astonishing speech, “that the collapse of the Soviet Union was a major geopolitical disaster of the century.” Putin clearly intends to restore Russia’s influence over the Commonwealth of Independent States, the vestigial association of former Soviet republics. “We need not turn this CIS space into a battlefield,” he said. “Rather we should turn it into a space of co-operation.” The idea that these are the two options being considered by Putin is not reassuring.

Is Putin’s long-run aim to restore the Soviet Union? Russians always insist that it would be impossible to turn back the clock now that people have grown accustomed to the whole range of Western freedoms—not least the freedom of information symbolized by the crowded Internet cafes along the Nevsky Prospekt. Yet there is a discernible nostalgia for the terrible simplifications of the old days. In a poll conducted in 2003, the Russian Center for Public Opinion found that 53 percent of Russians still regard Stalin as a “great” leader. The explanation is not far to seek. The collapse of communism has meant not just greater freedom but also widening inequality and a dramatic decline in average living standards.

Since 1989, the Russian mortality rate has risen from below 11 per 1,000 to more than 15 per 1,000—nearly double the American rate. For adult males, the mortality rate is three times higher. Average male life expectancy at birth is below 60, roughly the same as in Bangladesh. A 20-year-old Russian man has a less than 50/50 chance of reaching the age of 65. This has much to do with the round-the-clock consumption of cigarettes and booze—the typical St. Petersburg man walks around with a bottle of beer and a cigarette in one hand the way a Londoner carries his mobile phone—not to mention an attitude to road safety apparently inspired by the Mad Max films. It also reflects the long-term effects of the planned economy on the Russian environment and the near-collapse of the health-care system.

Exacerbating the demographic effects of increased mortality has been a steep decline in the fertility rate, from 2.19 births per woman in the mid-1980s to a nadir of 1.17 in 1999. Because of these trends, the United Nations projects that Russia’s population will decline from 146 million in 2000 to 101 million in 2050. By that time the population of Egypt will be larger.

All this helps explain why so many Russians might welcome a return to the USSR. Or perhaps it might be more accurate to say that they would willingly trade their own recent history for a version of China’s, which would give them the benefits of the market economy without the costs they associate with the collapse of the Soviet state.

Whether Putin can deliver that is a moot point; it is probably too late now for Russia to exercise the Chinese option. But what he can undoubtedly give Russians is a sense of geopolitical revival after the humiliations of 1989–91, which saw perhaps the swiftest decline and fall ever experienced by a great empire; for in military, diplomatic, and economic terms, Russia still remains a serious power.

Just consider Putin’s diary for a week this past June. On Monday he welcomed Tony Blair to Moscow. On Tuesday he had a phone call from President Bush. And on Wednesday his guest in St. Petersburg was Sonia Gandhi. Needless to say, all this gets blanket coverage on the television news. Still, there is substance behind the show.

Other world leaders have good reasons to hobnob with Putin. Blair came here to get his backing for African debt cancellation and the Kyoto Protocol, which Russia recently signed. Russia, is after all, a member of the G8. Bush wanted to hear Putin’s thoughts on reforming the United Nations. Russia is, after all, one of the five permanent members of the Security Council. And no doubt Sonia Gandhi wanted to talk economics. Russia is, after all, Asia’s number-one source of oil, gas, and other vital commodities.

Any British visitor to Russia instantly recognizes the symptoms of postimperial trauma. The place has the feel of the 1970s, right down to the terrible clothes, teeth, and hairdos. Yet those who wrote off Britain in the 1970s overstated its decline. The same mistake was made by a British journalist who recently compared Russia with Africa. This is not, despite the old Cold War joke, “Upper Volta with missiles.” There may be no going back to the USSR. But it is much too early to consign Putin’s Russia to what Soviet propaganda used to call the dustbin of history.