- Contemporary

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

- History

Probably the most repellent statement ever made by a contemporary American intellectual was that of Susan Sontag when she wrote: "The truth is that Mozart, Pascal, Boolean algebra, Shakespeare, parliamentary government, baroque churches, Newton, the emancipation of women, Kant, Marx, Balanchine ballet et al., don’t redeem what this particular civilization has wrought upon the world. The white race is the cancer of human history. It is the white race and it alone–its ideologies and inventions–which eradicates autonomous civilizations wherever it spreads, which has upset the ecological balance of the planet, which now threatens the very existence of life itself." (Partisan Review, winter 1967, p. 57.)

Sontag’s anarcho-racist language is on a par with an equally repellent statement made by a contemporary British intellectual, E. M. Forster: "If I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country" (from Two Cheers for Democracy). Not only repellent but stupid, since in betraying his country he might be betraying his friend into the hands of its enemies. In a fitful absence of mind, Mr. Forster forgot to repudiate the highest honors—Companion of Honour in 1953 and Order of Merit in 1969—that he had happily accepted from the government and land he was prepared to betray.

And then there is the comment just after September 11 by tenured history professor Richard Berthold at the University of New Mexico, who told his freshman class that "anyone who can blow up the Pentagon has my vote." Mr. Berthold is still teaching at UNM, but had he uttered a politically incorrect word about Jesse Jackson, Al Sharpton, or the Black Panthers he’d have been fired or, at the very least, suspended. Actually the university has administered a "cruel and unusual punishment"—Mr. Berthold won’t be able to teach freshmen for the immediate future, the university announced December 10, 90 days after the Pentagon and Twin Towers bombings.

I was reminded of these "blame America" reflections on noting publication of a book by University of Chicago professor Mark Lilla, The Reckless Mind: Intellectuals in Politics. He poses this question: "What is it about the human mind that made the intellectual defense of tyranny possible in the 20th century?" That question applies to intellectuals like Susan Sontag, an admirer of Ho Chi Minh and Fidel Castro, who described the September 11 tragedy as no tragedy at all but, to quote her words in the New Yorker, "an attack on the world’s self-proclaimed superpower, undertaken as a consequence of specific American alliances and actions."

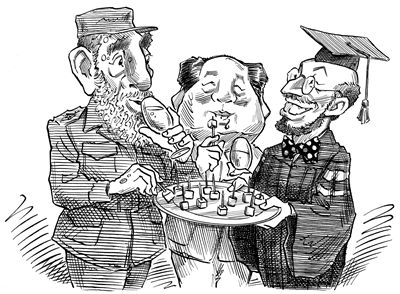

It is one of the anomalies of our time that it was highly intelligent people who willingly and actively supported Lenin, Stalin, Hitler, and Mao during the twentieth-century supremacy of these master genocidists. These irrationalist intellectuals—a "chorus for tyranny" Mr. Lilla calls them—all lived in democratic societies; their assent was thus born not out of fear but out of a conscious decision to ignore reason. Mr. Lilla has coined a phrase for these reckless minds: the "philotyrannical intellectual." This "social type," he says, included "distinguished professors, gifted poets and influential journalists [who] summoned their talents to convince all who would listen that modern tyrants were liberators." Perhaps they were inspired by Hegel, the nineteenth-century German philosopher, who wrote: "A mighty figure must trample many an innocent flower underfoot and destroy much that lies in its path." Osama bin Laden and his ilk would certainly agree with the observation of this Teutonic infidel.

These "philotyrannical" intellectuals are with us today, as they were back in 1932 when Theodore Dreiser, Sherwood Anderson, Erskine Caldwell, Edmund Wilson, John Dos Passos, Lincoln Steffens, Malcolm Cowley, and Upton Sinclair, among others, signed a joint letter endorsing the communist presidential candidate because, they wrote, "It is capitalism which is destructive of all culture and communism which desires to save civilization and its cultural heritage from the abyss to which the world crisis is driving it."

In his recently published study Public Intellectuals: A Study of Decline, Richard Posner, himself a public intellectual as well as a U.S. court of appeals judge, ascribes to them a "proclivity for taking extreme positions, a taste for universals and abstractions, a desire for moral purity, a lack of worldliness and intellectual arrogance." These attributes, he writes, "work together to induce in many academic public intellectuals, selective empathy, a selective sense of justice, an insensitivity to context, a lack of perspective, a denigration of predecessors as lacking moral insight, an impatience with prudence and sobriety, a lack of realism and excessive self-confidence." (For a devastating analysis of Judge Posner’s book, see Gertrude Himmelfarb in the February issue of Commentary magazine.)

The striking consequence of these failures to serve truth is their malignant influence on society. As Lionel Trilling once wrote: "This is the great vice of academicism, that it is concerned with ideas rather than with thinking and nowadays the errors of academicism do not stay in the academy; they make their way into the world and what begins as a failure of perception among intellectual specialists finds its fulfillment in policy and action."