- History

- World

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

The Early History

To break up the mutually growing infatuation between her son Arthur and the aristocratic but penniless governess Bertha von Kinsky, the Austrian Baroness von Suttner suggested Bertha apply for a position advertised in the Paris papers—housekeeper for an older gentleman. Bertha, realizing her untenable situation, applied and received the position. The older gentleman was the 43-year-old Alfred Nobel.

Bertha had worked for Nobel for only a short time when Arthur cabled that he could not live without her. She left Paris; they eloped and moved to Georgia in the Caucasus for eight years before returning to Austria. Her marriage did not, however, mark the end of her relationship with Nobel. Their friendship, carried on mainly through correspondence, continued for 20 years until his death.

During those 20 years Bertha, now Baroness Bertha von Suttner, became an accomplished writer and developed an interest in the nascent European peace movement. Her 1889 antiwar novel Die Waffen nieder (Lay down your arms) was not only a best-seller translated into 13 languages by 1905 but the bible for a growing number of peace advocates. That same year, peace-minded deputies from nine different countries met in Paris and formed an organization that became the Inter-Parliamentary Union, still operating today. Also in 1889 the first International Peace Congress was held in Paris.

As von Suttner became more influential in the peace movement, she continued to write to Nobel, sharing her views and asking for his support. In general, Nobel believed, as did many educated people of his day, that the progress of science and technology, the emphasis on mass education, a free press that would expose the private machinations leading to war, and the general equality of nations that came from the expansion of democracy would logically make war outmoded. He had less faith in people, however, than the progressive reformers of the time. The inventor of dynamite claimed that his war machines would bring the end of war more quickly than their peace congresses. “On the day when two army corps may mutually annihilate each other in a second, probably all civilized nations will recoil with horror and disband their troops.”

After Nobel read von Suttner’s appeal for peace in the Paris newspapers he wrote, “Delighted I am to see that your eloquent pleading against that horror of horrors—war—has found its way into the French press. But I fear that out of French readers, ninety-nine in a hundred are chauvinistically mad.” She ignored his comments and deluged him with her literature.

In 1893, Nobel wrote to Bertha that he would like to dispose of a part of his fortune as prizes for peace every five years for thirty years, assuming that “if the present system is not reformed in that time, we will all return to barbarism.” She continued to write him, enclosing tracts and brochures. He carefully preserved all the letters. In correspondence dated September 26, 1895, she encouraged Nobel to read them “not for the author, but for the work that is dear to her; throw to the wastebasket all those little papers, but keep at the bottom of your heart a voice that tells you here is a woman who despite the indifference and opposition her ideas encounter, perseveres in her task.” Within the following two months Nobel drafted the final form of his will and signed it. On December 10, 1896, he died.

|

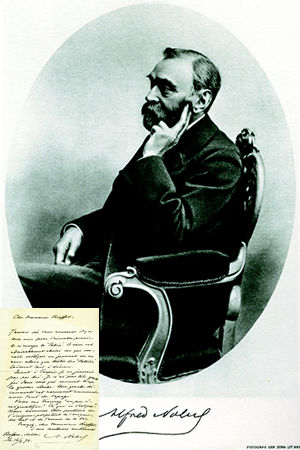

| Alfred Nobel This is one of the few portraits of Alfred Nobel, as he thought his visage unattractive. |

When Nobel’s will was made public after his death, it created a huge sensation. The never-married inventor and international businessman, whose fortune of 33 million Swedish kroner (U.S. $190 million in today’s currency) was created from more than 350 patents and the international corporations he established to produce his inventions, had not left any part of his estate to his many relatives. Instead, his will dictated that his holdings were to be liquidated, the cash invested in government bonds, and the interest used to create five prizes—in medicine/physiology, chemistry, physics, literature, and peace—to be awarded yearly. Those prizes were to be presented to the person of any country, man or woman, whose work in the preceding year had done the most “to benefit mankind.” In the case of the peace prize it would be awarded to someone who worked toward establishing fraternity among nations, reducing standing armies, or holding peace congresses.

Naturally the peace community, particularly von Suttner, was overjoyed, as the will gave public recognition and credibility to the movement. Several years passed, however, before its details were worked out. The will, probated in Sweden, survived the predictable contest from unhappy relatives, but there were other problems. Specifics were lacking, such as who would invest and manage the money. The court, however, respecting Nobel’s intent, established the Nobel Foundation.

In the case of the peace prize, however, Nobel’s intent was not followed. Nobel had identified the Norwegian Storting (parliament) as the entity to award the peace prize. At Nobel’s death Norway was part of Sweden. Swedish conservatives, concerned about the growing Norwegian independence movement, were afraid that Norway would use the prize to influence other countries to support it against Sweden. The executors of the will finally had to make compromises. Despite Nobel’s intent that the peace prize go to an individual, the final statutes said it could be split or awarded to an organization, thereby diluting its impact. (Nobel had specified that the prize go to an individual as he felt that more was accomplished by the inspired individual with resources than by an organization.)

|

| Jane Addams, 1860–1935 Jane Addams—pioneer social worker, feminist, and internationalist—represented the peace movement in the United States. She was awarded the peace prize in 1931. |

Finally, on December 10, 1901, five years after Nobel’s death, the first prizes were presented. Each laureate received a gold medal, a hand-painted diploma, and a statement of the cash award. The Norwegian parliament announced the peace winners: Frédéric Passy, the founder of the InterParliamentary Union and a friend of von Suttner’s, and Henri Dunant, the founder of the International Red Cross. Assuming that von Suttner’s persuasive arguments with Nobel were the reason for the inclusion of a peace prize, these initial awards surprised the peace community, including both Passy and von Suttner. In addition, the latter award upset many in the peace community, as the work of the Red Cross was not considered the work of peace as stated in the will. These initial awards thus opened the door to a broader interpretation of the will’s specifics that continues to this day.

For the next four years von Suttner watched as the prizes went to others. Alfred Fried, her colleague and editor of her newspaper, also called Die Waffen nieder, claimed her omission was “an infamy, an outrage.” Finally, in 1905, she was named the winner of the peace prize. Words from her diary show her emotions at the time: “she will not take the cash—she will take it—it was worth the effort—big difficulties: back and forth, the losses, travel fatigue, sleepless nights—remarkable, instead of joy, it also brings worries—it is still magnificent!”

Statesmen and Officials as Peace Laureates

Early recipients of the peace prize were European with one exception, Theodore Roosevelt. In his presentation speech, Gunnar Knudsen, speaking for the Nobel Committee, acknowledged “President Roosevelt’s happy role in bringing to an end the bloody war recently waged between two of the world’s great powers, Japan and Russia.” Roosevelt was a statesman who believed that arbitration should be used to settle conflicts between nations.

The outbreak of World War I devastated the peace movement and the idealism of its adherents. With a few exceptions, the postwar peace prizes were awarded to statesmen and politicians who negotiated treaties, boundary disputes, and in general promoted “fraternity among nations,” to use the words from Nobel’s will. Unfortunately many of these settlements quickly collapsed when new tensions arose.

Frank B. Kellogg, the U.S. secretary of state, received the peace prize in 1929 for his pact condemning war. Article I states: “The High Contracting Parties solemnly declare in the names of their respective peoples that they condemn recourse to war for the solution of international controversies and renounce it as an instrument of national policy in their relations with one another.”

Aristide Briand and Gustav Stresemann received the peace prize for the Locarno Pact (1926), which included a series of treaties with mutual guaranties and established borders, signed by Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, and Poland. In 1936 Hitler denounced the pact when he remilitarized the Rhineland.

The intrawar laureate list is long, and most of the names, such as Bourgeois, Dawes, Henderson, and Lamas, have little or no general recognition today.

Government officials continued to be chosen periodically after World War II. When supporters for West German chancellor Willy Brandt’s nomination were collecting recommendations, one letter from historian Golo Mann, son of Thomas Mann, stated the problem succinctly.

“Regarding Willy Brandt and the peace prize. Unfortunately I cannot approve of this at all. First, in my opinion, professional politicians should not receive the prize at all. When they do something for peace, they do only what they are paid and honored for. Second, if politicians were to receive the Nobel Peace Prize, then this should happen at the end of their career, just before their retirement, when what they have really achieved for peace is clear and proven. In the case of Willy Brandt, whom I esteem tremendously too, it is today still way too early. Stresemann and Briand received the Nobel Peace Prize for Locarno; a few years later one could only smile melancholically about this.” And he added a postscript. “PS: My mother has the same opinion.”

Despite Mann’s opposition, Brandt was awarded the peace prize in 1971 for his Ostpolitik (eastern politics), his continuing work toward reconciling West Germany with East Germany, Poland, and the Soviet Union.

|

| Ralph Bunche, U.N. undersecretary for special political affairs, holds a press conference in Leopoldville, Republic of the Congo, January 1963.

|

The dream of a lasting peace in the Middle East has been the basis for three Nobel Peace Prizes. Ralph Bunche, a member of the State Department, was assigned to the U.N. Special Committee on Palestine in 1947 and sent to Palestine in 1948 with mediator Count Bernadotte of Sweden at the conclusion of the British mandate over Palestine. When Count Bernadotte was assassinated, Bunche became acting U.N. mediator, attempting to settle the issues between the new state of Israel and its Arab neighbors. After 11 months of almost ceaseless negotiating, Bunche obtained the signatures on armistice agreements between Israel and the Arab states. The Nobel Peace Prize followed in 1950.

In 1978, Mohamed Anwar al-Sadat and Menachem Begin shared the peace prize following an agreement between Egypt and Israel known as the Camp David Accords. Again in 1994, the prize was shared among Palestinian Yasir Arafat and Israelis Shimon Peres and Yitzhak Rabin for the Oslo Accords.

Peace Laureates as Human Rights Advocates

|

| Italian translation of Menchú’s autobiography, I, Rigoberta Menchú, dictated to Elizabeth Burgos.

|

During the last 40 years the Nobel Peace Prize Committee has expanded the definition for peace so that it no longer applies to just “fraternity among nations.” Peace activism has come to include work within a country for the human rights of its citizens. Referring to the new emphasis on human rights, Nobel Committee chairman Edil Aarvik said to Professor and Nobel Prize historian Irwin Abrams in 1983, “The will does not state this, but the will was made in another time. Today we realize that peace cannot be established without a full respect for freedom.” This definition means that men and women working to stop imprisonment without trial, torture, censorship, and general injustice are thus peace activists and as such qualify for the peace prize. Albert Luthuli of South Africa, a recipient of the peace prize in 1960 for his nonviolent resistance to apartheid, and Martin Luther King Jr. (1964 prize), who spoke and worked tirelessly for civil rights in the United States, are the earliest examples of this new direction.

Politics and peace are always intertwined. The choices of the Nobel Committee call attention to oppression in various parts of the world. The Dalai Lama, spiritual and secular leader of Tibet, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989, the year the Chinese government imposed martial law on Tibet’s capital, Lhasa, in response to demonstrations by Tibetans seeking independence. The Chinese government then condemned the Nobel Committee for interfering in its internal affairs. Jose Ramos-Horta and Carlos Belo, leaders of the independence movement of East Timor, won in 1996, following a period of intense international interest in the future of East Timor and its independence from Indonesia. The plight of indigenous peoples in the Americas as the result of European colonization was addressed by awarding Rigoberta Menchú of Guatemala the prize in 1992, the 500-year anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s first voyage to the new world.

As one views the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize over the past 100 years, one finds the recipients have been generally worthy, particularly if the award was based on a body of work, not just a onetime treaty. The few notable omissions include Mahatma Gandhi, whose practice of nonviolent protest has been the model for so many. In a century known for its violence, the Nobel peace laureates remind us that men and women throughout the world are working to relieve suffering, stop injustice, and bring light into the dark places.

|

| The Dalai Lama.

|