- International Affairs

- Key Countries / Regions

- Middle East

- Security & Defense

- US Defense

- US Foreign Policy

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

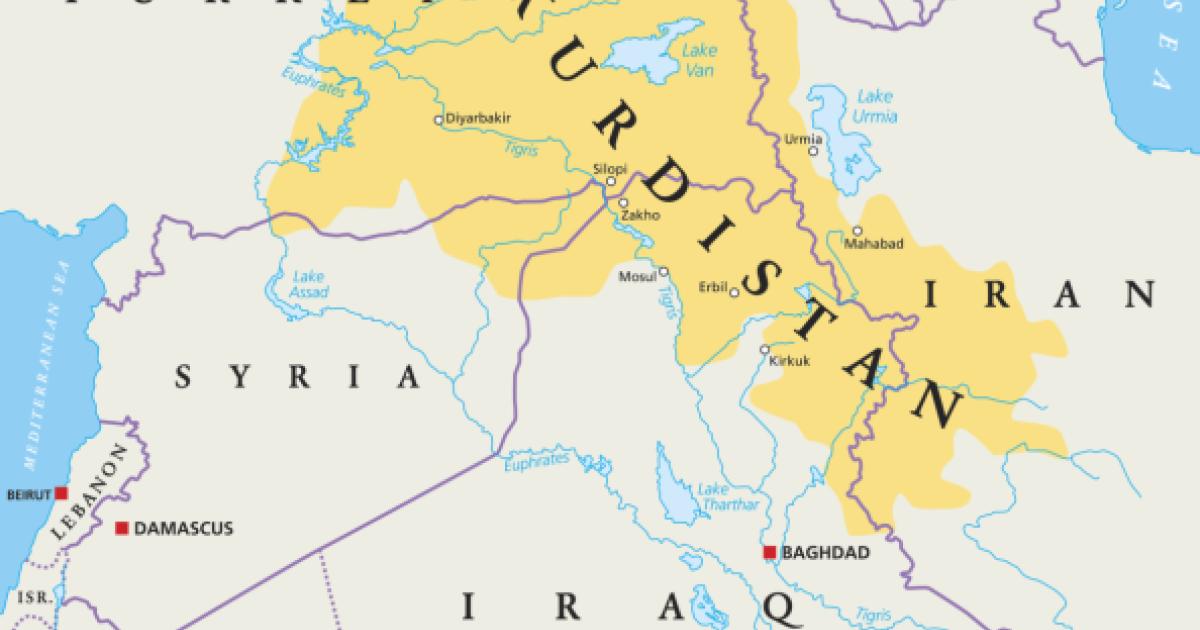

In April 2020, the US Department of State decided to support the opening of a dialogue between the Kurdish National Council (KNC), an umbrella organization of Syrian-Kurdish political parties close to the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) of Massoud Barzani, and the Democratic Unity Party (PYD), the Syrian branch of the PKK (Kurdistan Worker’s Party). At the end of May, the PYD founded the "Kurdish National Unity Parties", a coalition of 25 political groups, and in June, the talks between the Kurdish Unity Parties and the KNC began in earnest. The aim of these negotiations was, and still is, to reach a compromise regarding the political future of the Syrian Kurds’ autonomous administration thus far solely controlled by the PYD.

The fact that the US administration decided to invest in the political process flags a remarkable shift in its approach towards the Syrian Kurds: before, the cooperation with the PYD or rather its militia, the YPG (People’s Defense Forces), was exclusively of a military nature. Without the US Air Force supporting YPG and PKK through air strikes, they would have hardly succeeded in defending the city of ʿAyn al‑ʿArab (Kobanî) in September 2014 against. At that time, there was no direct armament of PKK fighters taking place. Because the PKK has been designated by the US as a terrorist group, the Pentagon would have had a problem openly arguing for direct cooperation. However, to solve this problem, a “new” military alliance was created. On October 10, 2015, the YPG and the YPJ (Women’s Defense Units) joined together with a Christian militia and a coalition of Arab units to form the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in order to cooperate in the fight against ISIS. The YPG would take command of this force and assume the responsibility for recruiting Arabs into it. Only pro-regime fighters were brought in. By mid-October 2015, the US was supporting the alliance with weapons – the goal was to capture ar-Raqqah, the “capital” of ISIS in Syria.

The Trump administration not only continued the cooperation with the SDF and the YPG, but strengthened it further – authorizing in May 2017 the arming of “Kurdish elements” within the SDF – that is directly arming the YPG. Thus, the Pentagon clearly outplayed the State Department in its desire to cooperate with the PKK; military “needs” in Syria had been assessed to be more urgent than the diplomats' wishes to respect NATO alliances and, in particular, Turkey’s concerns. The defeat of ISIS had absolute priority – even though the American administration was well aware that the PYD and YPG were responsible for severe human rights violations in the parts of Syria they took control of in 2012. According to organizations such as Human Rights Watch, the United Nations, and KurdWatch, the YPG is recruiting children, some as young as 12 years, to be engaged in combat. Moreover, members of parties of the KNC, particularly members of the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Syria (KDP-S) and the Yekîtî are regularly arrested, intimidated and even killed, their offices attacked and shut down. Obviously, the understanding of democracy held by the YPG, PYD, and PKK is not shared by Western countries, but corresponds instead to the model of “people’s democracy”, a political concept characteristic of the former socialist countries. There is one ruling party, and all other groups must subordinate themselves to it. Competing parties are not allowed to participate in the political process. However, these aspects have been downplayed by the different US administrations thus far.

Given these circumstances and particularly the imbalance of power between the parties concerned, is there any real chance that the Biden administration can successfully negotiate a power sharing compromise between the KNC and the PYD/PKK dominated "Kurdish National Unity Parties"? Why should the Biden administration be more successful than Massoud Barzani, former president of the Kurdistan Region – under his supervision, the PYD and KNC agreed in October 2014 to set up a 30-member power-sharing council to run the Kurdish region in Syria and to form a joint military force in order to fight ISIS. However, the agreement – like its two predecessors – never materialized.

Still, there is a chance – because the KNC as well as the PKK currently both have interests in such a compromise. For the KNC, a power sharing agreement is attractive, as it would allow them not only to resume their political activities in the North-East of Syria, but also offer them access to positions in the administration and to political decision-making structures. On paper, the parties have already voted for a solution similar to that of 2014 – that is, the establishment of a Shura Council that would have political decision-making power for the Kurdish-majority areas of Syria. Both sides would have 40 seats for their own people and the right to name another ten persons who are independent, but nevertheless close to them. Additionally, an agreement is important for the KNC as the first step toward the return of Syrian-Kurdish refugees currently living in Iraqi-Kurdistan and Turkey. Many of them left the country due to persecution by the PYD, and many of them are close to one of the parties of the KNC.

At first glance, the PYD and thus the PKK do not seem to have any interest in an agreement – no matter what, they would have to give up power to the KNC. However, since ISIS was defeated in Raqqah in October 2017, the argument that it is necessary to work with the YPG in order to fight ISIS has lost momentum, and the follow-up thesis, that the YPGs presence is inevitable to prevent an ISIS return, is less convincing. This is particularly true because any mid-term solution to the potential re-emergence of ISIS would have to involve a much broader diplomatic and political investment. Thus, it is of no surprise that Mazlum Kobane, the commander of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), initiated the US-led dialogue with the KNC in October 2019. Not only had the Trump administration decided to pull American troops out of Syria then, but Turkey invaded substantial regions of the Kurdish-controlled northeast of Syria at that time. It was the fourth Turkish military operation after “Operation Euphrates Shield” in 2016, the establishment of military posts in Idlib in 2017, and “Operation Olive Branch” in the beginning of 2018. Already the 2018 attack had been identified by many as a betrayal of the Kurds by the U.S. Kobane, thus, saw the talks as a vehicle to expand the engagement with the United States in Syria beyond what has largely remained a strictly military alliance and in doing so bolster the PYD’s international legitimacy beyond a leftist romanticization of “Rojava”.

It is against this background that the Biden administration now has a chance to negotiate a power sharing agreement between the two parties. However, in order to stabilize the Kurdish administered region, to promote democratic structures, to maintain Syrian unity and to create a safe base of operations for US-engagement in Syria, it should be led by the following principles:

- A transitional council should be established. Within this council, power must be equally exercised by the two parties.

- Within a year, this council shall prepare free elections for the region`s administration. These elections shall be monitored by the UN.

- Party militias such as the YPG and the “Rojava Peshmerga”, an Iraqi-Kurdistan based militia of Syrian Kurds linked to the KNC, shall be dissolved and a new defense force established – controlled by the civil administration. The example of Iraqi-Kurdistan clearly shows that competing party militias tasked to defend a region are not part of the solution, but part of the problem.

- All Syrians having fled the region – mostly to Kurdistan-Iraq and Turkey – must have the unconditional right to a safe return.

- Victims of human rights violations must be compensated.

- The administration shall have the right to sell a certain percentage of the oil produced in the region. It may be paid at least partly by food deliveries in order to provide support for the population of the region and to prevent corruption.

- A regional constitution shall be drafted which clearly defines the cultural as well as the political competences and responsibilities of the region. This regional constitution must respect the unity of the Syrian state as well as the cultural and political rights of all ethnic and religious components living in the region administered. The KNC already worked on such a constitutional draft in 2016 – even though it was never adopted – and on its vision of a federal Syrian state.

There is no guarantee that such an agreement – or any agreement – can be reached. Neither the Syrian regime nor large parts of the Syrian opposition which identify any form of decentralization as separatist, nor major external actors such as Turkey, Iran and Russia support such a solution. Moreover, there would certainly be major resistance by both parties against the above drafted road map. Neither will the PKK be willing to dissolve the YPG, nor will the KNC want to give up the idea of bringing the Rojava-Peshmerga to Syria.

However, the alternative to a sustainable, Kurdish-Kurdish understanding is to sacrifice the region and its population to the despotism of the PKK – and, in the longer run, to the barbarous revenge of the Syrian regime. Likewise, to come to another agreement that falls far short of good governance and respect for human rights wouldn’t be worth the paper it is written on.

Dr. des. Eva Savelsberg is president of the European Center for Kurdish Studies in Berlin and an expert on the contemporary history of the Kurd in Syria, Iraq and the European Diaspora. Following an interdisciplinary approach, she is particularly interested in state building, nationalism, minority rights, and constitutional questions.