- US

- Contemporary

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

- History

In recent years, the right-wing Catholic twins who run Poland have advanced two articles of political faith: first, that the strength and moral integrity of the Polish nation is built on the rock of the Polish Catholic Church and, second, that the weakness and corruption of Polish public life are a result of the failure to cleanse it of former collaborators with the communist regime. So what happens when the new archbishop of Warsaw turns out to have signed a secret agreement in the 1970s to spy for the communists?

What happens is the scene, at once dramatic and grotesque, that unfolded in Saint John’s Cathedral in Warsaw on January 7. A Mass is held, supposedly to install the new archbishop, Stanislaw Wielgus, who had assumed office the previous Friday despite press revelations of his heretofore hidden past. Instead of being installed, however, the archbishop, decked out in all his glorious episcopal vestments, announces his resignation. Seated in the front row of the congregation, the president of Poland, Lech Kaczynski (twin one), starts to applaud. (Rumor has it that he personally intervened with the pope to bring this about.) But he rapidly stops applauding when he hears from the back of the nave a raucous chorus: “No! No! Stay with us!” The people who are shouting are his people, the faithful who listen religiously to Radio Maryja (“Mary”), the influential right-wing Catholic radio station that helped bring him and his brother, Prime Minister Jaroslaw Kaczynski (twin two), to power.

Apparently those rank-and-file Catholics don’t agree with their president in thinking that the compromised archbishop should step down. It’s our church, right or wrong. Except that the church can’t be wrong, can it? So they do what people often do when they don’t like what they hear: blame it on the media. “The media lie,” they chant in the street afterward.

| The unforgettable scene in the Warsaw cathedral illuminates, like a medieval morality play, the dilemmas with which half of Europe has been wrestling since the end of communism. |

The primate of Poland seems to agree with that part of the congregation. In an extraordinary homily, Cardinal Jozef Glemp rails against the judgment being passed on Archbishop Wielgus on the basis of what Glemp dismissively calls “scraps of paper and documents photocopied for the third time.” Yet he knows the pope has already accepted Wielgus’s resignation, with regret but also with approval. So is the primate attacking the pope?

That unforgettable scene in the Warsaw cathedral illuminates, like a medieval morality play, the dilemmas with which half of Europe has been wrestling since the end of communism. To remember or forget? To open the files or leave them under lock and key? To purge or not to purge? Some would argue that this case shows, once again, how dangerous it is to open Pandora’s box. Better to let bygones be bygones, as Spain did after Franco.

I think the opposite is true. The Wielgus affair perfectly illustrates the importance of a timely, scrupulous, fair, and comprehensive uncovering of the dictatorial past, in all its complexity. After all, the truth will out in the end. Would it be better if, 50 years from now, Polish Catholics discover from the long-sealed archives that their beloved archbishop—subsequently perhaps primate and, who knows, even second Polish pope—had been supping with the communist devil?

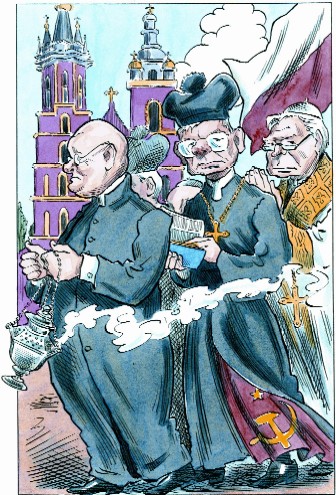

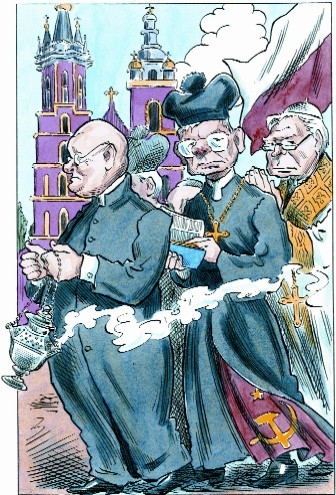

To be sure, sensationalist press stories, based on leaks, are not the best way to go about this. A little knowledge is a dangerous thing. But the cure for a little knowledge is more knowledge, and still more, until people begin to see the historical truth in all its shades of gray. Already this scandal has blown to smithereens the simplistic black-and-white picture of the past constructed by the Kaczynski twins, Radio Maryja, and the like. For them, anyone who walked in clerical black was whiter than white, and anyone who had ever, however briefly, sported the communist red was black as black can be. Now the archbishop in black turns out to have been the red spy, and all the colors are mixed up together.

The process of uncovering this messy past will continue, hard though the Polish church hierarchy has tried to resist it. Apart from anything else, younger and uncompromised Polish Catholics are demanding it. Another senior Polish priest has just resigned. A clergyman in Krakow, the Reverend Tadeusz Isakowicz-Zaleski, has published a book naming 39 alleged clerical collaborators, four of whom he says are now bishops.

We will never know the full facts, however, because many files of Department IV (which dealt with the church) of the communist security service were destroyed at the end of the communist period, which is perhaps why Wielgus felt safe from his own gray past. It caught up with him, however, in the form of a microfilm copy of a file belonging to the foreign intelligence department, to which he committed himself to report under the pseudonyms “Adam Wysocki” and then—very suitably—“Grey.” I have read some facsimile pages from that file (available on the web). Far from being mere “scraps of paper,” they are almost textbook samples of a typical communist secret service file, with the wooden language and distorted perspective (almost invariably overstating the informer’s willingness to collaborate) familiar to me from the documents of other Soviet-bloc security services.

| It’s our church, right or wrong, say the rank-and-file Polish Catholics. Except that the church can’t be wrong, can it? |

The story they tell is equally familiar. Stanislaw Wielgus, an academically and personally ambitious man from a poor, conservative, rural background, wanted to study in West Germany with German theologians such as the present pope. He signed an agreement to collaborate to get there. He says he didn’t harm anyone; that’s what they all say. But the whole point of such an intelligence system is that individual informers do not understand the value, in the larger jigsaw, of the apparently innocent pieces they reluctantly provide to the importunate secret police.

Many people signed similar declarations. But many others didn’t and paid the price—not being allowed to go and study abroad, for example, or not going on to have successful careers. As human failings go, this was not very serious. Those of us who had the good luck to grow up in a (relatively) free country should ask ourselves: what would I have done; would I have signed? But a man who did sign should obviously not be the archbishop of Warsaw, especially because he did not come clean about his past until forced.

| The cure for a little knowledge is more knowledge, and still more, until people begin to see the historical truth in all its shades of gray. |

When I first traveled to Warsaw, nearly 30 years ago, when it was still under communist rule, I chanced upon a monk in Saint Antony’s Church who led me round, pointing out memorial tablets indicating that the person had died at Katyn in 1940—killed, that is, by the Soviets, a fact flatly denied by official communist propaganda. Since I did not then speak Polish and he apparently spoke no other living language, communication was difficult. But finally I found a way. “Fortis est veritas,” I said, “et praevalebit!” (“Truth is strong and will prevail!”).

I will never forget his grin of sheer delight. It was a good motto for Poland then, and I think it’s still a good motto for Poland now. And not just for Poland.