- Campaigns & Elections

- State & Local

- The Presidency

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

There may be no second acts in American lives, as F. Scott Fitzgerald once suggested, but that doesn’t keep us from second-guessing politics, politicians, and the art of campaigning.

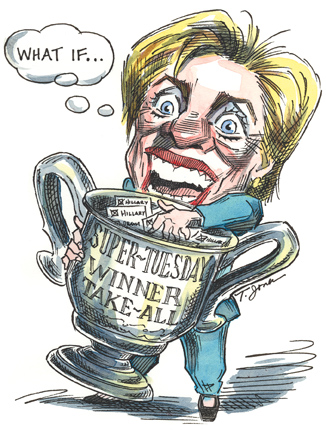

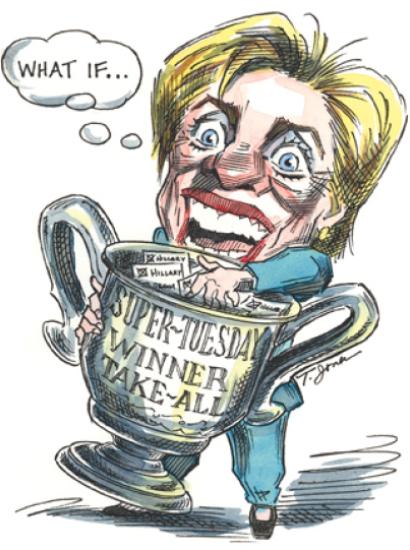

The 2008 election is no exception. Should Hillary Clinton have paid more attention to those caucuses in February instead of going for a Super Tuesday knockout? Would the Republican contest have turned out differently if Rudy Giuliani had contested Iowa and New Hampshire or if Mitt Romney had not so deeply immersed himself in conservatism? And where would we be without YouTube, talk radio, Matt Drudge, and the 24-hour news cycle?

With all of that in mind, here are five “what if?” questions to consider.

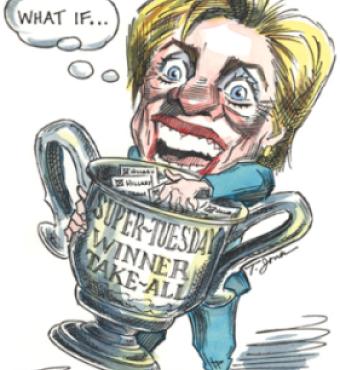

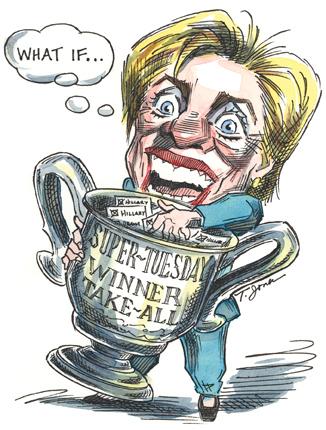

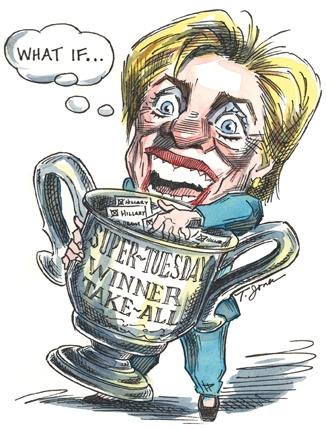

WHAT IF DEMOCRATS HAD CHANGED THEIR DELEGATE MATH?

“If we had the Republican rules, I would already be the nominee,” Hillary Clinton told reporters in May, in the days leading up to the Indiana–North Carolina doubleheader. For good measure, she voiced the same thought the day after splitting the vote.

She had a legitimate beef. She won the popular vote in every megastate except Illinois, but because her party allots delegates proportionally, as opposed to the Republicans’ winner-take-all rules, those wins didn’t translate to an insurmountable delegate lead. This negated a big win on Super Tuesday; though she won handily in California, New Jersey, and her adopted New York, Clinton saw her lead grow by a mere 44 delegates by night’s end on February 5. March and April were no kinder. She scored victories in Ohio, Texas, and Pennsylvania, but because of the Democrats’ quirky rules, those three states added up to a net gain of only 14 delegates— an advantage offset by Barack Obama’s landslide win in South Carolina, with a net pickup of 13 delegates.

Apply the GOP’s delegate rules to the Democratic primary, and it would have been a different story. Rather than trailing in the delegate count, Clinton would have racked up a lead of 400-plus delegates, and she would be facing John McCain today. Twenty years ago, however, Democrats instituted a new set of rules that turned their party’s delegate selection into the political equivalent of a kids’ soccer game, where everyone goes home a winner.

As the Reverend Wright would say, that chicken has come home to roost.

WHAT IF THE GOP HAD PLAYED BY THE DEMOCRATS’ RULES?

If all the GOP delegations had been chosen proportionally, McCain wouldn’t have begun to distance himself from the field after winning the January 29 Florida primary (recall that McCain edged out Mitt Romney 36 to 31 percent but claimed all 57 delegates). A week later, on Super Tuesday and thanks to different rules, McCain still wouldn’t have achieved closure. He won nine states that day, but under our hypothetical count, six would no longer be winner take all. The 309 delegates he won in those states would dwindle to more like 142. California doesn’t help matters. Instead of capturing 158 of 170 delegates, McCain’s 42 percent performance would be worth only 71 delegates.

Take yourself back to the spring: McCain is not the strongest of frontrunners— in his home state of Arizona, he wins on February 5 with only 47 percent of the vote. And he’s strapped for cash. Perhaps this encourages Romney, who has won seven Super Tuesday states, to dig deeper into his personal fortune and prolong the race to March 4 (Ohio, Texas) and beyond. Maybe Air America seizes on the confusion in the Republican ranks and launches its own version of Rush Limbaugh’s Operation Chaos (an invitation to voters to cross party lines to confuse the results). Then again, given Air America’s puny listening audience, would anyone have noticed?

WHAT IF CALIFORNIA HADN’T VOTED UNTIL JUNE 3?

The Golden State usually holds its primary on the first Tuesday in June, which is when it would have been weighing in on Obama versus Clinton if the state’s leaders hadn’t opted to advance the presidential primary to Super Tuesday. The political elite got what it wanted: California mattered (kinda, sorta), with Obama and Clinton working the state and flooding its airwaves. What they missed out on was the big enchilada. June 3 was the Democrats’ last hurrah, with primaries in Montana and South Dakota. If California had been among the fold, the Golden State would have become Clinton’s Alamo—two weeks of campaigning, after the May 20 vote in Kentucky and Oregon, to plead her case to the superdelegates.

And it would have been historic. That June 3 vote came one day before the fortieth anniversary of the fabled California primary fight between Eugene McCarthy and Robert F. Kennedy. McCarthy entered that contest as a practitioner of “new politics” and as the darling of college campuses. Kennedy, trailing in delegates and the popular vote, desperately needed a California win to gain momentum heading into the national convention. Kennedy got his win by stitching together a coalition of working-class whites and minorities (most notably, United Farm Workers’ leader Cesar Chavez). Forty years later, Clinton campaigned with Chavez’s sister-in-law (and UFW co-founder) Dolores Huerta. By the way, California was a winner- take-all state in 1968. Sorry, Mrs. Clinton.

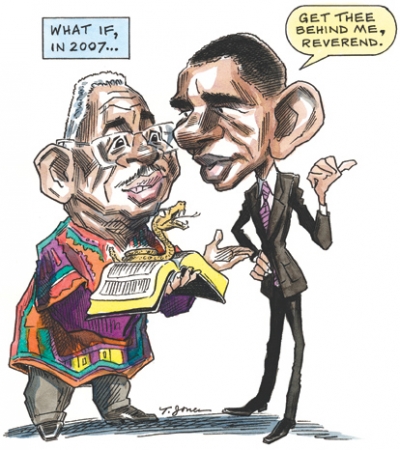

WHAT IF OBAMA HAD DECIDED WRIGHT WAS WRONG?

Instead of a clumsy one-two—equating his pastor to his white grandmother, then parting ways with his spiritual mentor when Wright was no longer politically tenable—let’s suppose Obama had decided a year earlier to distance himself from not only the controversial minister but also the larger issue of religious hate speech.

In an address at the National Press Club in the spring of 2007, soon after announcing his candidacy, Obama, in my what-if scenario, takes on the Reverend Wright in particular and, without naming names, all black leaders who engage in racial ambulance chasing. Perhaps the speech generates positive press and cements Obama’s image as a spokesman for the post–Civil Rights generation. It almost certainly guarantees a visible fight with the Reverends Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton.

All of which means that race, an issue that didn’t come to the forefront of the Democratic race until Obama’s speech in Philadelphia in mid-March 2008, would have appeared much sooner on the campaign trail and would have dogged the candidate as he tried to amass delegates. Perhaps it would not have mattered to Democratic primary goers, but it might have weighed on the minds of the superdelegates, whose support proved critical to Obama in the nonhypothetical campaign.

WHAT IF CLINTON HAD CUT LOOSE A KEY STRATEGIST?

You were expecting Mark Penn, who left the Clinton campaign in April, but that’s too obvious. Rather, what if Bill and Hillary had gone their separate ways once he had left office and she had secured her Senate seat? A freed Hillary would not have been dogged by questions about the complexity of her marriage or how she intended to keep her ex-husband largely contained to the East Wing of the White House. And, as a divorcee, she could have better related to a neglected part of the electorate that the Democrats need come November: only 59 percent of single women came out for the 2004 presidential election, compared to 71 percent of married women.

But Hillary’s newfound freedom might have come at a tangible cost: the financial freedom to keep her struggling campaign afloat with personal loans. According to the Clintons’ 2005–06 joint tax returns, she earned $1.05 million in Senate salary, plus nearly $10.5 million in book income. The former president, meanwhile, collected $1.2 million in his White House pension, $29.5 million in book income, and a whopping $51.8 million in speech income. Hillary’s no pauper, but without her husband’s income stream (or a sharp divorce attorney), she might not have had the kind of deep pockets that enabled her to twice make personal loans to her campaign.

This unusual election cycle will work itself out soon enough. Its “what if?” questions will keep political commentators busy for years to come.