- US Labor Market

- Economics

- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

- Budget & Spending

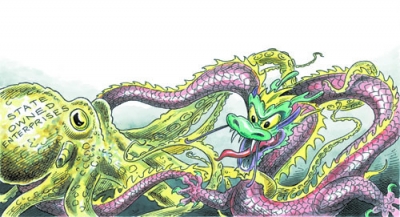

Those who speak for China’s government insist that during the past thirty years the state and private sectors have been “flying wing to wing.” They officially deny that state-owned enterprises have expanded at the expense of private enterprise, pointing out that the private sector’s share of production value, profit, employment, and growth rate exceeds that of the state. Hybrid and interlocking asset ownership by state, non-state, and foreign capital is still encouraged, they assert.

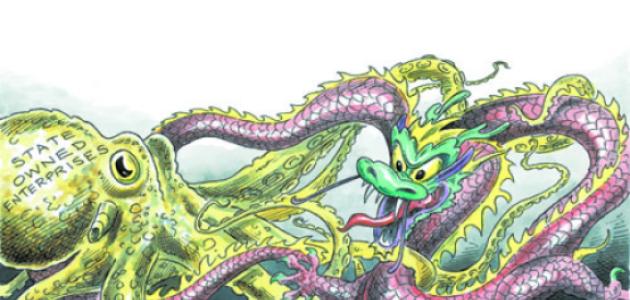

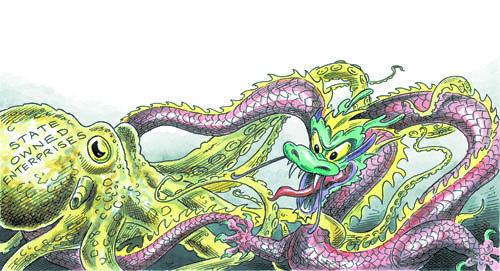

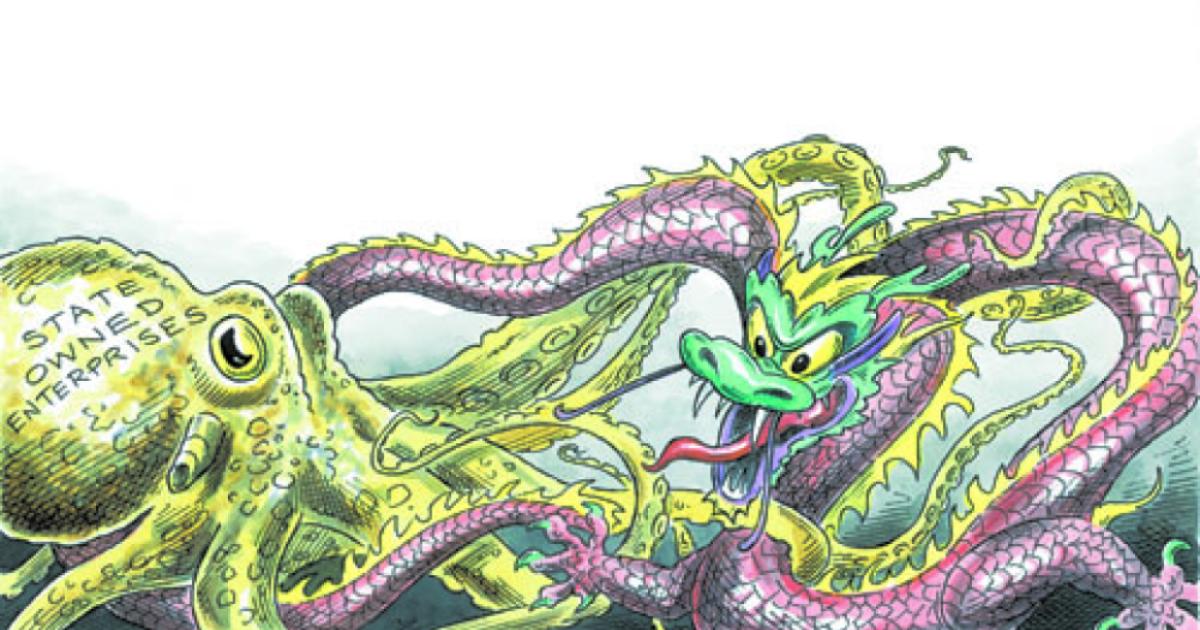

But most academics and journalists contend that such economic figures are unreliable and selective. Thus we are witnessing a heated debate in China on whether the state sector is making a comeback after decades of official encouragement of private enterprise (a reversal dubbed guojin mintui, or, the state advances as the private sector retreats), and if so, what the implications are for China’s economy.

The advance and retreat show themselves in many ways. The state still refuses to let private companies enter many key industries, especially those monopolized by state-owned enterprises; the government recently has intervened more vigorously into the economy; the government has allocated more resources to state firms than to private companies; and state firms have expanded into competitive industries and grown bigger.

The Chinese government began encouraging private-sector growth in the national economy, while downgrading the role of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), with the introduction of market-oriented economic reforms in the early 1980s. When China officially announced economic reforms and an open-door policy in 1984, the SOEs were urged to initiate a “responsibility management system.” But they failed to reverse their money-losing behavior. Then, in the early 1990s, Beijing started structural reforms of the SOEs by “grasping the big, letting go of the small”—retaining some large, vital SOEs while allowing most of the country’s medium and small businesses to become private. In 1999, the central authorities further redefined SOEs’ status, allowing them to remain in only three economic domains: industries related to national security, natural resources that the state monopolizes, and industries that produce public goods and social welfare.

Many SOEs had to abandon the competitive industries to private businesses. State-owned enterprises almost disappeared in food and beverages, textiles and apparels, home appliances, and other consumer-goods industries. Legally, non-state-owned enterprises were allowed to enter even such industries formerly monopolized by the state as finance, electricity, telecommunications, railroads, civil aviation, and petroleum. As a result, the share of SOEs in China’s industrial production fell from approximately 80 percent at the outset of the reforms to about 30 percent in 2008.

Their fate, however, was far from sealed. In 2003, the State Council set up a new organ, the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Committee (SASAC). This agency was determined to revitalize the SOEs and to reorganize them from money-losing into profitable firms through restructuring and consolidation. Li Rongrong, the chairman of the SASAC, declared that major industries including electricity generation and transmission, oil and petrochemicals, telecommunications, coal, civil aviation, and shipping should be exclusively owned by the state, excluding any domestic private entities.

In the meantime, Beijing was welcoming and attracting foreign investment to the SOEs. Indeed, the new policies benefited the SOEs’ performance. They began to make money, reaping a profit of $147 billion in 2006. Among 149 centrally controlled SOEs under the direct supervision of the SASAC, nineteen were on the Fortune 500 list. The SOEs had started to resurface.

State-owned enterprises also gained impetus from the 2008 global financial crisis. Most of the Chinese government’s 4 trillion yuan ($586 billion) stimulus package, already earmarked for rebuilding infrastructure such as railroads, highways, airports, and construction, was contracted to centrally controlled SOEs. Moreover, these enterprises enjoyed the privilege of borrowing from state banks. In 2009, around 80 percent of bank loans, 9 trillion yuan ($1.4 trillion), went to SOEs.

BIG ENTERPRISES GET BIGGER

As the global financial crisis weighed on China’s economy, exports declined and bankruptcies and the unemployment rate rose. Beijing issued a “Plan on Revitalization of Ten Industries” in early 2009 to encourage large SOEs in steel, automobile, shipbuilding, equipment, and other industries to merge with medium and small private enterprises, thus transforming them into giants that could compete in the world market.

The SOEs, supported by financing from central and local governments, made an impressive comeback after 2008. Among the major mergers and acquisitions in 2009:

- In the steel industry, the Shangdong Iron and Steel Group, long a money-losing SOE, acquired private Rizhao Iron and Steel. This created the second-largest steel company in China. The Baoshan Steel Group, a famous SOE, acquired private Ninbo Steel. According to the government’s plan, other big state-owned steel groups are supposed to merge about 45 percent of the country’s steel production capacity by this year.

- In the oil industry, China Petroleum (CNPC) acquired most of the non-state oil companies in Heilongjiang province. Almost no private gas stations can now be found in northern China. More ambitiously, the two oil giants, CNPC and CPCC (China Petroleum and Chemicals), are planning to buy banking and trust companies.

- The China National Cereals Group invested and purchased private Mengniu Dairy, the largest-ever deal in the Chinese food industry. Its business goes far beyond food and beverage to include residential and commercial real estate. It is now one of the “land kings” in upscale areas of Beijing.

- In Sangxi, the provincial government ordered reorganization of the coal industry. The share of private capital in that industry is to be capped at 30 percent.

Such SOE acquisitions and mergers have taken place in almost every industry, including automobiles, shipbuilding, civil aviation, and finance. Currently, the SOEs enjoy a monopoly over almost all of China’s resource industries—petroleum, telecom, electricity, tobacco, coal, civil aviation, finance, and insurance—forcing out private enterprises.

Furthermore, these SOEs have priority in going public and having access to financing. Most centrally controlled SOEs are listed in the Shanghai and Shenzhen composite indexes. Their capitalization has risen rapidly. With abundant financial resources and backed by political power, these special-interest groups can easily merge with and acquire other companies and exercise monopoly behavior in many markets. In addition, their growing liquidity has flowed to property and stock markets, thus inflating a bubble economy.

Recent data show that 80 percent of the profits earned by centrally controlled SOEs come from fewer than ten huge conglomerates, including CNPC, China Ocean Oil (CNOOC), China Telecom, China Mobile, and China Telecommunications. Most of the other SOEs either have overcapacity or are mismanaged, and must rely on government subsidies and credit to survive. At the same time, many non-state enterprises are in worse shape because they have no access to government loans and tax credits, and many private enterprises in coastal areas have shut down. Thus, the SOEs’ advance has not only promoted a threatening price bubble but also increased structural imbalances in the Chinese economy.

MONOPOLISTS CREATE A REAL ESTATE BUBBLE

One of the adverse effects of the advance of the state-owned sector has been the real estate bubble.

According to China’s law, all urban land belongs to the state. But local governments can transfer the land-use right (for no more than seventy years) of certain sizes of land to private or public bidders. The winning bidders then become landlords, and can resell their land-use right for a certain plot of land to developers for residential and commercial development.

Since the Beijing government liberalized the real estate market in 1992, the nonstate sector has been the major player in this market. But the share held by SOEs has been gradually rising—from an initial 8 percent to 60 percent. Many central and local SOEs that were never before involved in real estate have been competing for a share of this booming market. According to official data, over 70 percent of the 136 centrally controlled SOEs, including China Chemical, China Railroad, and China Metallurgy, have entered the real estate market.

In the wake of the global economic slowdown, most Chinese manufacturing companies have experienced overcapacity. Their executives saw in the real estate market an easy way to earn a profit. Relying on low-cost loans from state-owned commercial banks and high credit ratings, they won land auctions in “golden districts” of Beijing, Shanghai, and other metropolitan areas that smashed price records and created a number of “land kings.” This has created a public outcry.

These new landlords are not rushing to resell their land to developers for residential construction. Because the supply is limited, these land kings usually hoard real estate and attempt to corner markets, expecting their holdings to grow further in value. As a result, land in many urban areas lies idle even as housing remains scarce. According to recent news reports, the vacancy rate for new condominiums in many major cities exceeds 50 percent, while 85 percent of residents cannot afford to buy even a single unit. Over the past four or five years, China’s land and resources prices have quadrupled or more. Housing has become a source of social turmoil, an unstable factor in society.

PRIVATE ENTERPRISE, CHINA’S GROWTH ENGINE

Many Chinese scholars argue that in a market economy, government should act merely as a regulator and not a stakeholder. They worry that the surge of state-owned enterprises has grave ramifications and signals a potential return to a command economy. Among their specific concerns:

- State-owned monopolies have combined assets and power in many industries to limit market competition. This action brings market failure and widespread corruption.

- Because SOE revenues depend more on government spending and less on market demand, their behavior may fail to boost consumer spending and help the country achieve a more balanced economy. It would certainly change the transaction costs for transforming China’s economic growth models.

- Relying on government loans and subsidies instead of innovation and technological progress could make the SOEs less efficient than private companies.

- The SOEs pay high salaries and bonuses to their executives and employees, which means less money for the government and shareholders.

- Because many SOEs have invested in risky projects, bad loans will increase if the bubble bursts and triggers a bank crisis.

Private enterprises have become the driving force of the economy. According to official statistics, private enterprises now account for 65 percent of the nation’s GDP, 80 percent of newly added jobs, and 65 percent of government tax revenue. In 2009, private enterprises saw industrial production rise 18.7 percent, compared to 6.9 percent for state enterprises; revenue increase 18.7 percent, compared to a 0.2 percent decline for SOEs; gross profit rise 17.4 percent, compared to minus 4.5 percent for state firms; and employment go up by 5.3 percent, against 0.8 percent for the state firms.

In light of these data, many intellectuals are calling for the government to loosen its grip, return legitimate rights to the private sector, and revitalize nonstate enterprises.

Beijing seems to have begun paying attention. As a first step toward addressing the critical housing problem, in February 2010 the SASAC ordered seventy-six large central SOEs whose core business was not real estate to retreat from the property market. That action is now regarded as part of a broader government plan for SOEs to divest and thereby rein in fast-rising housing and land prices.

Apparently, the authorities also are responding more broadly to the advance of the state sector. In late 2009, the government agreed at its Central Economic Conference to promote private enterprises to create jobs, increase market access for private investment, and protect the legitimate rights and interests of private investors.

In March 2010, Premier Wen Jiabao announced an important new policy—“Wen’s Four Guidelines,” as nicknamed by the media. With the global financial crisis easing, Beijing has started to ponder an exit strategy from its stimulus program in order to diminish the state role and encourage private and foreign investments. These guidelines include the following developments:

- Encourage and guide private investment in currently state-controlled sectors such as infrastructure for transportation, telecommunications, energy, public utilities, scientific and technological programs for national defense, and affordable residential construction.

- Promote private innovation and upgrading through research and development, and participate in state-managed science-technology programs.

- Encourage and guide private enterprises to participate in restructuring and reorganizing SOEs through buyouts, shareholding, or joint shareholding actions.

- Set up a sound administrative system to serve and guide private investment and amend unfavorable laws and regulations.

At the same time, Li Rongrong, head of the SASAC, has pledged that state-owned enterprises will gradually retreat from competitive sectors to make way for private enterprises to expand.

If all these new policies are implemented, some analysts say, it will reverse the trend of “advance of the state, retreat of the private sector.” Some $6.7 trillion in private capital would replace the government stimulus plan and become the new engine for China’s post-crisis economic growth.