- History

Two films graced the cinemas of the United States—and Europe—this past year that are worth noting for the light they shine on the past as well as the current sensibilities of our chattering classes. Both cover the same period: May and the first days of June 1940 when the fate of the world hung in the balance. The first, Dunkirk, supposedly covers the escape of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) from France as German panzer divisions, having broken through the French defenses at Sedan, rolled toward the Channel ports and appeared to be on the brink of cutting off and destroying the BEF before it could escape. The second film, Darkest Hour, records the political arguments at the highest level of the British government as to whether Britain should attempt to do a deal with Hitler or fight on to the bitter end at the moment that the escape from Dunkirk was occurring.

Dunkirk is a thoroughly dishonest movie. Its intellectual heart, if it has one, aims to show the “little” man, caught in the maw of events over which he has no control. The movie opens with a few British soldiers desperately attempting to run away from German soldiers, who are shooting at them. They run by a few French soldiers, who make a cameo appearance and then disappear. But we never see the Germans. In fact, we never see them throughout the film—only the occasional aircraft dropping bombs. As for the British side of the picture, we see the cowardly, the hopeless victims, slaughtered by German bullets, the little sailors, and only occasionally a few British officers. It is as if the only thing that mattered in the historical events of Dunkirk are the cowards and the slaughtered. We do not see the British soldiers—or the French soldiers for that matter—who held off the Germans in desperate fighting, dying or heading off into five years of captivity; we do not see those coordinating the ships or Spitfires; and only in the distance do we see a disciplined, organized mass of soldiers patiently waiting with their mates to escape. In the end, Dunkirk depicts the worst, but then in this post-modern world, heroism, discipline, self-sacrifice are things of the past and why would movie audiences want to see such odd aspects of the human condition.

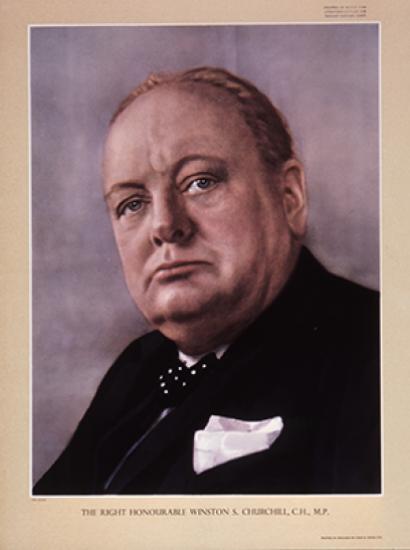

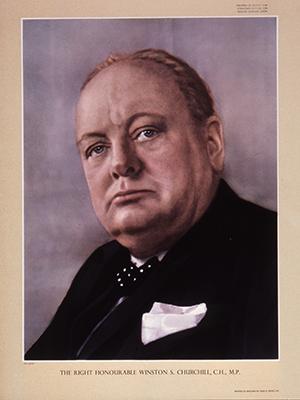

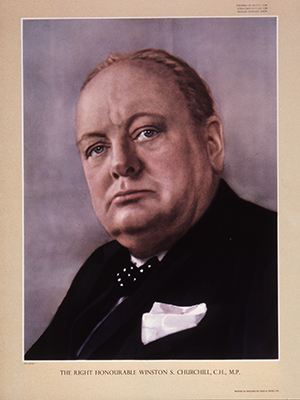

Darkest Hour presents a very different picture of the events. There are a few quirks in the film: Churchill never journeyed on the Tube; nor did he share his doubts with the common folks, or, in fact, with anyone. But those quibbles do not detract from an extraordinary film and acting performance. It is the heart of that perilous time that Darkest Hour gets right. What is important is that Churchill understood the terrible moral as well as strategic danger that Adolf Hitler and his crew of murderous thugs represented. In an uncertain hour, with the tide of the seemingly unbeatable Wehrmacht rushing ever onwards, Churchill recognized that there are some things worse than dying, a recognition that flies in the face of modern wisdom. And so in furious debate with Halifax and Chamberlain, Churchill stood against what appeared to be the tide of history and the fact that for many in the Conservative Party, there was no good reason to continue to fight in a hopeless cause. And oh, does Gary Oldham catch the brilliant eloquence of Churchill, who, as Halifax notes in the movie, mobilized the English language in support of his cause.

If ever there were a decisive moment in the history of the Second World War, it was this point, where British statesmen had to weigh whether the gamble that the United States and the Soviet Union would enter the war instead of waiting on the sidelines was worth the terrible price that Britain would have to pay. Churchill was the only one who understood the moral price Britain would pay if she failed to take that gamble. And he was the only individual who had the eloquence to speak the harsh truth and get the British people to rally behind him. The movie captures all of that. It is a monument to real heroism in an age where those at the highest level tweet instead of thinking and where historians believe that leadership does not matter in determining the course of history.

Williamson Murray serves as a Minerva Fellow at the Naval War College. He graduated from Yale University in 1963 with honors in history. He then served five years as an officer in the US Air Force, including a tour in Southeast Asia with the 314th Tactical Airlift Wing (C-130s). He returned to Yale University, where he received his PhD in military-diplomatic history under advisers Hans Gatzke and Donald Kagan. He taught two years in the Yale history department before moving on to Ohio State University in fall 1977 as a military and diplomatic historian; in 1987 he received the Alumni Distinguished Teaching Award. He retired from Ohio State in 1995 as a professor emeritus of history.