- Military

- The Presidency

- US

- History

- Revitalizing History

Today, most historians and many Americans rate Abraham Lincoln as one of the greatest presidents (if not the greatest) in our history. Yet, in the summer of 1864 (a full year after the Union victory at the battle of Gettysburg and the capture of Vicksburg) Lincoln was so unpopular that a fair number of leaders within his own political party supported convening a second nominating convention to drop him from the presidential ticket.1 Growing war fatigue throughout the North and concern that Lincoln would lose to his likely political opponent, General George McClellan, had conservative Republicans looking for a different candidate who could end the war with honor. On the other end of the ideological spectrum, the “Radical Republicans,” fearing Lincoln would cave to conservatives and end the war without abolishing slavery, nominated General John Fremont (the Republican standard bearer in the 1856 election) for president as a third-party candidate. Virtually no one in Washington, DC believed Lincoln could win, a faction that at least for a time included President Lincoln himself as he drafted a detailed memorandum to ensure an orderly transition between his administration and McClellan’s assuming they would be taking power after the election (Lincoln wanted to avoid the disastrous developments that occurred between his own election in November 1860 and his inauguration four months later in March of 1861).2

Moreover, in August of 1864, Lincoln was so desperate for a political game-changer that he actually drafted a letter to be delivered to Jefferson Davis, the President of the Confederacy, offering generous terms to end the war where the South got to keep their slaves if they stopped fighting and rejoined the Union. Fortunately for our country he decided to sleep on the idea first, and after rising the next day, thought otherwise, and discarded the letter, recommitting himself to leading the Union to a victory where the slaves were freed and the Union was restored under the philosophy and principles of our Founding.3

This essay will examine Lincoln’s leadership during those darkest days of the war where in the face of seemingly insurmountable challenges and overwhelming adversity, Lincoln ultimately found the strength to continue on when so many (including some key supporters) were ready to give up the cause. In the end, Lincoln’s formidable political skills, wisdom, and judgment played a pivotal role in the Union victory, but before that was possible, the North had to survive the toughest days of the war. This period was a testament to Lincoln’s personal courage (both physical and moral) and sheer mental toughness. When these traits were needed in extraordinary measure to shore up a waning war resolve in the North, Lincoln was the man of the hour…but it didn’t look that way from the beginning.

Indeed, as he was sworn in as our sixteenth president there was little evidence to suggest he would overcome the daunting political challenges he was facing. True, prior to his election as president Lincoln had received some favorable notoriety for his quirky toughness, like the well-traveled stories that he had won nearly every boxing match he ever had, a number reputedly in the hundreds, and during the campaign stories circulated that he had been elected as his company’s commander during the little known “Black Hawk War” of 1832, pointing to some ability to inspire others when courage and toughness were needed. Moreover, in 1858, Lincoln was perceived by many as the winner of the “Lincoln-Douglas debates” indicating some political skill, especially since Stephen Douglas was widely considered as our country’s greatest orator at the time. Still, it must be pointed out, Lincoln ultimately lost that election to Douglas and rather than earning a reputation as an imposing political figure, Lincoln was more known as a political loser after campaigning unsuccessfully for the House of Representatives, Senate, and vice presidency all by the time he accepted his Party’s nomination in 1860.4

Moreover, although Lincoln was the undisputed winner of the 1860 election, he did so while garnering just 40% of the popular vote and with virtually no support in the South—hardly an overwhelming mandate to tackle arguably the most divisive and consequential political dispute in our nation’s history. To all of this we must also add that his physical appearance was often mocked. At six feet four inches, Lincoln was our tallest President (a record that still stands to this day) and walked with an unusual gait. Cartoon depictions of Lincoln in the newspapers were less than generous about his looks. Considering all of this, more than a few wondered if Lincoln was up to the task at hand.

Yet, while Lincoln was painfully aware of all of these detracting factors, over time he somehow turned them all into strengths. The more people got to know him, the more they appreciated his humble, unassuming style and captivating story-telling abilities. He was especially quick-witted with a keen sense of humor and knew how to endear himself to friends and foes alike. Despite losing his mom at an early age, not being especially close to his dad and growing up impoverished, Lincoln had a good sense of himself and confidence in his abilities, which also proved a crucial asset during times of acute challenge and stress. His faith in God provided added strength and all of that along with his study of the classics (especially philosophy and history) gave him very strong convictions of what was right and wrong and the resolve to endure tough times to accomplish his duty.

The Hard Times: 1861–1864

As the Confederate batteries were firing on Fort Sumter, Lincoln was still back in Springfield, Illinois preparing for his inauguration as James Buchanan served out his final four months as our fifteenth president. Lincoln understood the peril of the moment and worked back channel with southern leaders, trying to persuade them not to secede from the Union. Despite these efforts however, just a couple of weeks after the election, South Carolina became the first to secede. Several other States followed in December, with others still in the new year. Ultimately, Lincoln was not able to persuade the South to stay in the Union. Faced with that grim development, Lincoln gave strict guidance that Union forces would not fire on Confederate forces. Through it all, Lincoln never lost sight of his highest strategic aim; to eventually end slavery while restoring the Union. If war was to come, the South would have to start it.

Ever the realist, after Fort Sumter, Lincoln quickly pivoted to raising an army to rapidly squash the rebellion. He knew he needed a new strategy to do it. Despite significant advances in weapons technology over the past several decades that might have influenced world leaders to re-think their strategic approaches, Union leaders in 1861 were still largely enthralled by the Napoleonic paradigm of warfare where armies maneuvered with close-ordered formations until they were ready to initiate epic battle. The goal of the big battle was to destroy the opposing army bringing about total victory. Napoleon had perfected this approach at the Battles of Jena and Austerlitz during his reign as Emperor of France and Lincoln envisioned a similar approach to crushing the rebellion by the summer of 1861.

Lincoln entrusted overall leadership of the Union Army to General Winfield Scott who had first distinguished himself almost 50 years earlier as a young Brigadier during the War of 1812. Scott further brandished his reputation during the Mexican-American War by capturing Mexico City. By 1861, Scott was known to be both studied and experienced. By then in his 70s and considerably overweight, Scott was still considered the embodiment of the Napoleonic style for Union forces. Following Lincoln’s guidance, in the summer of that year Scott ordered General Irvin McDowell, the field Commander of the Union Army of the Potomac, to engage the Confederates in epic battle in Virginia.

It could not have gone worse. In July, Union forces were routed at the Battle of Bull Run near Manassas and Lincoln quickly found himself searching for other generals who could master the Napoleonic style. He found little success. Over the next several years Lincoln went through a posse of generals attempting to destroy the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in hopes of capturing their capital city, Richmond. These generals included names such as George McClellan, Ambrose Burnsides, Joseph Hooker, and George Meade. In battle after battle, however, Union generals proved themselves not up to the task.

It was not for lack of trying. In the summer of 1862, the vaunted General McClellan, who had a well-cultivated reputation as a strict disciplinarian who was well-studied in the art of maneuver and the Napoleonic-style, orchestrated a daring landing on the Virginia Peninsula aiming to outflank Confederate forces to quickly capture Richmond. The campaign was an utter failure with Union forces being thoroughly defeated by General Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia during the Seven Days Battles. Later that year at Fredericksburg, Union forces under Burnsides attempted to dislodge Confederate forces dug-in atop of high ground and were slaughtered. The following year in 1863, General Hooker engaged the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia near Chancellorsville, another battle that ended in utter failure for Union forces.

Even when they managed to win a major battle, Union Generals were not able to capitalize. For example, after General Lee’s disastrous decisions at Gettysburg, which after three days of battle left the Army of Northern Virginia in an untenable position necessitating their withdrawal, the Union Army did not pursue Lee to force his surrender. That was a missed opportunity for the Union and put Lincoln in a position where he was not able to translate this rare battlefield success into significant political momentum for the Union cause.

While operationally the Union fared better in the West, capturing Vicksburg in July 1863, thereby consolidating control of the strategically significant Mississippi River, and by the end of that year, ensuring that Kentucky, Missouri, and most of Tennessee were back in the Union column; all knew that the rebellion would continue until Lee’s army was defeated and Virginia returned to the fold. Still, Lincoln took note of these victories in the West and eventually promoted to high command the generals responsible for them, including U.S. Grant, William T. Sherman, and George Thomas.

By 1864, after years of setbacks, Lincoln abandoned the strategy of maneuver warfare in pursuit of epic battle and settled instead for a protracted war of attrition. In this line of thinking, because the South could not match the North in terms of manpower and war-related resources, by bleeding them out (both literally and figuratively), the North would eventually win the war. Although the strategic effects of these decisions were not immediately felt (they will be covered in detail in the next essay of this series published in mid-January), in retrospect, this fateful decision was clearly the beginning of the end for the Confederacy.

Courage and Toughness—Leadership Lessons from Lincoln

The major take-away from this low point of the war was that it was a near miracle that the Union continued to fight on considering how much war fatigue pervaded the North and the significant in-fighting within the Republican Party. As chronicled by renowned historian Stephen Oates, by the summer of 1864 one prominent Republican wrote, “there are no Lincoln men.”5 Imagine what the course of American history would have been had prevailing opinions carried the day? However, this is where leadership can make all the difference. Lincoln had the constitutional authority to lead, the right vision, and was resolved to accomplish his duty. He inspired the North to faithfully forge ahead. That took incredible mental toughness and moral courage.

In the process, Lincoln also exhibited remarkable physical courage. When Confederate Cavalry Commander J.E.B. Stuart led his forces on a raid of Washington, D.C. in July 1864, Lincoln went to Fort Stevens to check on the defenses and encourage his men. During that visit there were Union soldiers shot and killed in his presence and bullets were reported to have nearly hit the president himself. Yet, he pressed on. Moreover, only one day after Union forces finally captured Richmond in the first week of April 1865, President Lincoln personally walked through the streets of the fallen Confederate capital to get a firsthand assessment. There is simply no equivalent example in modern U.S. history. It would be like Truman walking the streets of Berlin in May 1945 or George W. Bush walking the streets of Baghdad in April 2003. The inhabitants of Richmond (who knew what Lincoln looked like from photos in local newspapers and at six foot four inches he clearly stood out) were reported to have stared at him as he walked by, awed by his presence and courage.

His mental toughness, too, enabled him to resist caving to popular opinion and from the pressures of other leaders. Just as he did with passage of the XIII Amendment in the U.S. House in January 1865, when Lincoln simply refused to budge when all of his advisors told him there was no way that amendment would pass the House floor, with his generals, Lincoln urged them to carry out his intent and when they didn’t—he didn’t lose his temper, he just lost those generals, replacing them with others ready to get the job done. Key here is that it was not only his steadfastness to principles, but also his temperament. During the hard years of the war in the face of this apparent obstinance from his own Cabinet and from his generals, Lincoln seldom lost his cool. He consistently demonstrated stolid resolve, treating those who cautioned otherwise with dignity and respect, yet insisting that they carry out his orders nevertheless, sometimes using colorful storytelling to make his point. Important leadership lessons from our sixteenth president—thank you Abraham Lincoln.

Chris Gibson is a decorated Army combat veteran, a former Member of Congress, and a Participant of Hoover’s Working Group on the Role of Military History in Contemporary Conflict. This essay was drawn from Gibson’s latest book, The Spirit of Philadelphia: A Call to Recover the Founding Principles, published by Routledge in 2025.

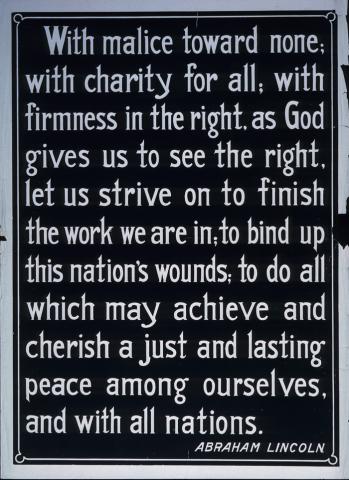

1 Stephen B. Oates, With Malice Towards None: The Life of Abraham Lincoln (New York: Penguin Books, 1977), p. 430.

2 Ibid., p. 429.

3Ibid., p. 430.

4 Lincoln was the runner-up to William Dayton, General John Fremont’s eventual running mate in 1856. In fact, the only real experience Lincoln had with national leadership before becoming president was a fairly unremarkable two-year term as a U.S. Representative, a seat he won on his second attempt, and that was over a decade before he became president-elect.

5 Oates, With Malice Towards None, p. 430.