- History

“Periodization” is a trendy academic term for historians’ use of particular (and sometimes arbitrary) chronological terms—often in reference to wars in general, and in particular to when they started and ended.

Were there really “three” Punic Wars rather than just one that continued for well over a century from 264-146 BC, ending only with the Roman absolute destruction of Carthage?

We talk about the “Peloponnesian War” (431-404 B.C.) that ended with the defeat of Athens. Yet a few scholars see the Spartan-Athenian “war” breaking out earlier in 460, and continuing with off-and-on fighting for almost a century—until Sparta was crushed by Thebes at Leuctra in 371 and ended formally its hostilities with a resurgent democratic Athens.

In others words, what sometimes looks like a war to end all wars can turn out to be a breathing space or lull between rivals.

How many Mideast wars have there been—five, six, or more? Or maybe just one that began in 1948 with the birth of Israel and the attack on the Jewish state by its neighbors, and continues today through its several incarnations?

Democracy is said to discourage aggressive imperialism (as if democratic Athens and republican Venice were not imperialist). In this way of thinking, Germany was reborn in 1945 as something quite antithetical to everything that had come before. At last and for good, Berlin was fully integrated into Europe on peaceful and co-equal terms.

Or was it?

Of course, we abhor any suggestion that Germany is not a liberal democracy. Certainly, it has reinvented itself over the last eight decades as a humane and decent society, its present generations so often unfairly blamed for the sins of their long-dead ancestors. Yet that fact of postwar German moral success makes even more striking the recent course of German history that is beginning to resemble a sort of postmodern Prussianism on the trans-Atlantic stage.

On September 9 1914, German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg’s secretary, Kurt Riezier, produced the so-called Septemberprogramm—a plan for imperial Germany to annex or control much of an envisioned defeated Europe and Western Russia.

After the first heady victories of World War I, the German army looked like it would defeat the allies in mere weeks and Russia within a few months. Hollweg and Riezier dreamed of a Pan-Germanic Europe under Kaiser Wilhelm II that would rival the power of Great Britain and the United States.

Almost four years later, under the harsh terms forced upon a defeated Russia by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, for a moment Germany had achieved the plan’s visions in the east.

But the unexpected entry of America into the war in April 1917 thwarted the Western European complement of the Septemberprogramm, and Germany surrendered in November 1918.

The idea of a Pan-Germanic Europe did not quite die with the end of imperial Germany, despite depression, political chaos and the general distrust that Germany had incurred from all of Europe.

For the next 21 years, various German academics, politicians, and extremists all sought to remedy the verdict of the Treaty of Versailles and to fulfill what they thought was Germany’s natural but sidetracked destiny since unification in 1871.

New imperialists boasted of an even larger Germany to come than the Kaiser had ever dreamed, now to be surrounded by a ring of defeated client states that lacked free political or economic will. Everything and everywhere from Moscow to the Atlantic and from the North Pole to the Sahara would be subject to control from Berlin.

Hitler outlined such mad visions in his rambling autobiographical Mein Kampf and his Nazi Party went to war in 1939 to fulfill them. Of course, the subsequent ruin of Germany in 1945 seemed to have put to rest for good any further idea of a Pan-Germanic Europe, in the manner that Napoleon’s crumbling idea of a French European Union was ended at Waterloo.

After all, Germany was now divided and occupied.

France and Britain, but not Germany, went nuclear.

NATO and the European Common Market replaced German nationalist ambitions with ideas of partnership with its fellow democracies.

The half-century long Cold War threat of the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact all but made Germany a client of America.

But after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the reunification of Germany in 1990, and the establishment of the European Union in 1993, Germany gradually reassumed its historic continental influence. The ensuing predominance predictably could not be entirely explained by its large territory or population. Over the next thirty years, yet a third incarnation of German power emerged, following the failed imperial efforts of 1914 and 1939.

German statecraft made several brilliant decisions. If in the past, military force had failed to obtain European dominance, perhaps its refutation might—as if money and industry could do what spiked helmets and motorized divisions had not. And rather than threatening neighbors why not seduce them?

Germany was able to square the circle of controlling the European Union by all but disarming. What it saved in military expenditures by enlisting the subsidized protection of NATO and the United States, it invested in a new mercantile Pan-European system of break-neck exporting while carefully limiting importation. The world benefitted by superb German goods, and German respect for international organizations and rules.

Yet German foreign policy insidiously became largely synchronized with the interests of huge German banks, and financial, petrochemical, engineering, manufacturing, automobile, and pharmaceutical companies.

One way of thinking of the European Union is not as a utopian dream of shared power among like-minded consensual democracies. Rather, more cynically, the EU has resulted in the veritable end of nationalism and, with it, of the independence of Germany’s weaker continental rivals. Or more directly, the EU states have voluntarily surrendered their sovereignty to a union in Brussels that is, whether by intent or accident, virtually run by Germany.

In the past, German arrogance coupled with military power failed to absorb Europe. In the present German international citizenship and pacifism have nearly succeeded. In every recent major European crisis of national sovereignty, Germany had the final say, often with the result that others grew only relatively weaker.

Germany’s open borders policy has caused utter chaos in front-line Mediterranean states like Greece, Italy and Spain.

When Berlin began to have second thoughts that too many illegal immigrants made their way into Germany, it began sharing its self-induced problem with its neighbors. Or rather, Germany began ordering Eastern Europeans to mimic its own failures to assimilate and integrate impoverished, mostly Muslim males arriving from the war-torn Middle East—but always under the banner of the ecumenical European Union. The rising popularity of Vladimir Putin’s Russia in Eastern Europe and the Balkans as the new orthodox Byzantium is directly attributed to growing backlash at Germany and its insistence on forcing EU values on others with different worries.

Germany determines the value of the Euro, the common European currency that is more or less a renamed Deutsche Mark. It is pegged artificially lower than the prior Mark to ensure more German exports and make more expensive foreign imports. Berlin’s neighbors, of course, imported more and exported less, and as a default increasingly bought German—often on easy credit.

After the 2008 global financial meltdown, Germany proved a harsh taskmaster in demanding its own recklessly liberal loans be paid back fully by mostly bankrupt southern European nations. It is no exaggeration to say that Greece and Italy, and perhaps even Spain, never recovered from the 2008 implosion, and under the financial terms arranged by EU bureaucrats and German banks will likely not soon fully reach their prior levels of economic growth and standards of living.

Such imperiousness might suggest that some EU countries would like to leave the union. But Germany stubbornness with a departing United Kingdom has signaled that leaving is almost more trouble than it is worth.

Donald Trump is furious that NATO members in Europe are in arrears on their promises to increase defense spending. But they hesitate, largely following Germany’s lead. Currently it has the largest account surpluses into the world and runs a massive trade surpluses of $65 million with the United States.

Germany could vastly increase defense spending to share NATO’s burden, given it is the largest European member and for years the most vulnerable to foreign invasion.

Berlin could further negotiate over much of the massive debt owed by southern EU members, given that they are becoming near third-world countries in futile efforts to service such sums—and that Germany has become enriched by a union that so often impoverished others.

Germans could build better relations with the United States by ensuring that tariffs were either eliminated or reciprocal, and thereby slash half their trade imbalances with America. They might improve global commercial health by stopping their warping of international trade and finance to ensure an end to gargantuan Germany surpluses. And they could aid frontline Mediterranean states to secure their borders, and thereby end illegal immigration where it injures the most fragile of European members.

But then if Germany were to do all that, Germany would not quite be Germany—at least as proud Germans once again envision themselves as mostly misunderstood victims, who are blamed for their successes by mostly envious others.

In terms of economic, political, cultural, and social power and influence, Germany exercises far greater sustainable influence in Europe and beyond than it ever has since 1871, despite a vastly reduced territory, a static population, and being virtually disarmed.

Until recently, German ascendance was seen as an entirely good thing. Germany’s industriousness and wealth, lack of military power, and democratic institutions both enriched Europe and reassured neighbors that peaceful Germans were now more European than German, and were working hard for 500 million other Europeans. The past was long dead and buried.

Or so it seemed.

But the rub was not just the decisions that Germany has recently taken seemed designed for national aggrandizement. It is the manner and attitude in which they were arrived.

In other words, immigration, finance, Brexit, trade, and NATO were mostly non-negotiable issues. Germany decided and other EU members nodded.

If the U.S. dissented on German energy deals with Vladimir Putin’s Russia, its laxity in NATO contributions, or it mercantile trade policy, then the U.S. was demonized as something similar to Germany’s own autocratic past. That growing animus that might explain why Germans poll the most anti-American of all European states, regardless of which party controls Washington, and why recently one German analyst advocating going nuclear to ensure Germany a full range of foreign policy options. A cynic might suggest that Berlin resents a third effort in a century by the United States to curb its ambitions.

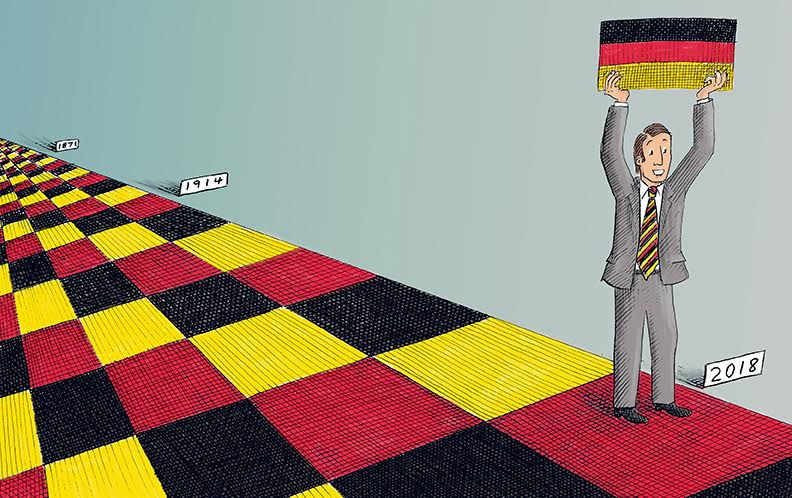

Future historians may argue that the birth of a united German state in 1871 was a century-long checkered project, aimed at consolidating German power and eventually adjudicating Europe from Berlin. If so, they might conclude that a subsequent 100 Years War started around 1914 and wound down after 2018—and that all the horrific ups and downs in between were detours to victory.

GET MORE commentary from VictoR Davis Hanson.

Hanson explains the fascinating history of how both factions trace their roots back to Roman times - the urban radicals who favored equality, and the rural traditionalists who favored liberty. You'll learn the important parallels between these ancient movements and their modern counterparts in both progressives and conservative populism.

Simply complete the form below and we'll send you Dueling Populisms now.