- Security & Defense

- US Defense

- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

Hoover senior fellow Victor Davis Hanson went to Iraq in early October 2007, his second visit to the country. He reflects on what he saw:

From Ramadi to Taji and in various hot spots in Baghdad and Diyala province, almost all the Marine and Army units I visited expressed the belief that there has been a sudden, almost inexplicable shift in the pulse of the battlefield. Sometimes, with little warning, thousands of once-disgruntled Sunnis have turned against Al-Qaeda, ceased most resistance, and begun flocking to government security forces and begging the Americans to stop both Al-Qaeda and Shiite militias.

Commanders are cautious. They know that if the Shiite-dominated government in Baghdad continues to seek revenge for decades of suffering at the hands of Sunni Baathists, any reconciliation will fail. So, among other tactics, thousands of American officers are desperately pressuring Iraqi ministries to start distributing the vast wealth of Iraq’s oil revenues to Anbar, the province at the heart of the “Sunni triangle,” and Diyala before the Sunnis revert to insurgency.

The brilliance of those Army and Marine officers has not been fully appreciated. I will return to that theme. I met scores of officers with doctorates and master’s degrees, from majors to colonels, who are simultaneously trying to defeat Al-Qaeda gangs and Shiite militias, rebuild government facilities, arbitrate tribal feuds, repair utilities, and train Iraqi army and police personnel. The men and women in the field of fire believe not just that we can win by securing Iraq but that they are doing a moral good by giving millions a chance at a different way of life. Whatever one’s views on the war, it seems to me morally reprehensible that anyone would slander these soldiers, comparing them to terrorists or their general to a betrayer. In today’s military, we see the representatives of the moral upper crust of American society, and as long as they are engaged, we need to support them in the efforts to stabilize an Iraqi constitutional government. We may come to the day when the military itself thinks victory is beyond our resources or not worth the cost, but from what I saw, as during my 2006 visit, we are not there by a long shot.

Just as on my previous trip, I am left with three general impressions about the military:

First, our Army and Marine forces are too few and overextended. The United States must either radically enlarge these traditional ground units or scale back its commitments in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. Through constant rotations, we are burning out gifted officers and lifetime professionals—and will lose their priceless expertise if they begin, as I fear, retiring en masse out of sheer exhaustion.

Second, there is more optimism among the battlefield soldiers about success than among analysts in Baghdad. The sudden decrease in violence has left many units stunned: the Iraqis who had been trying to kill them are suddenly volunteering information about terrorists and mines and clamoring to join the joint security force. Usually one expects those behind the desk to be the optimists; the soldiers in danger, the pessimists. Instead, there is genuine feeling on the front that after four frustrating years of ordeal, at last there are tangible signs of real, often radical improvement.

Third, as a supporter of some four years of the now-unpopular effort to remove Saddam and leave a democracy in his place, I continue to have only one reservation, albeit a major one. The U.S. soldier in the field is so unusually competent and heroic that one comes to despair at the thought of losing even one of them. As a military historian I know that an army that can’t take casualties can’t win, but I confess, after spending 16-hour days with our soldiers in impossible conditions, to wondering whether the entire country of Iraq is worth the loss of just one of these unusual Americans. I understand both the lack of logic and the amorality in such a sweeping statement—given the tremendous suffering and sacrifice on the part of millions of brave Iraqis. Yet I feel it nonetheless.

TO PACIFY AND TO TRANSFORM

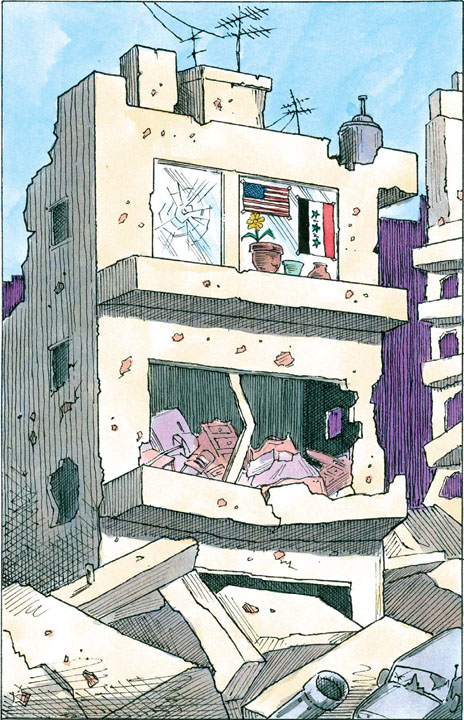

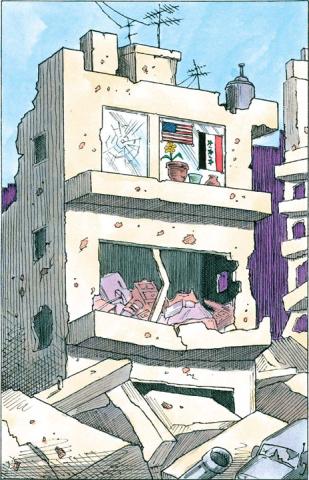

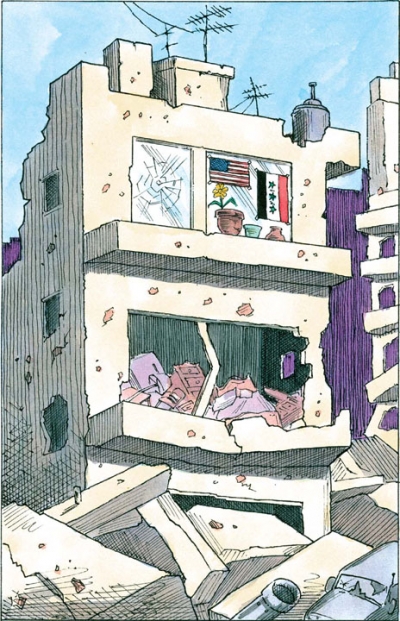

The military is pulling out all the stops in Iraq in the fullest military, economic, political, and social sense. Americans are trying not just to defeat the insurgency but to take Iraq from its primordial past to the twenty-first century within four years—a herculean task.

Traveling through Iraq, one notices the enormous U.S. investment in trucks, cars, military equipment, bases, houses, reconstruction, Iraqi outfitting— literally billons evident to the eye, everywhere, at every moment. And the wear and tear on that equipment is also evident. I wouldn’t be surprised if 30 percent of our equipment were worn out to the degree that it wouldn’t make sense to haul it back, that the machinery would be better off left to help with the transition in Iraq. Humvees have sprung doors, broken glass, missing pieces, in addition to the wear from sand and heat. I think the American people should accept that after Iraq we will have an enormous tab to pay to re-equip the Air Force, the Marines, and the Army.

Vietnam War–era veterans have been brought in to lecture on counterinsurgency, along with veterans of recent wars from Panama to Afghanistan. Interpreters are no longer scarce; in fact, too many are trying to join up. Some of the best are Iraqi-Americans, who know American idioms and deeply appreciate being Americans. Hundreds of U.S. personnel are working on IEDs (improvised explosive devices), not just countertechnologies and aerial surveillance but sophisticated methods of learning how they are made, how the bombers function, and how they are paid and maintained. Thousands of reserve and retired engineers have come to Iraq to build and to advise Iraqi contractors.

A common slur about such reconstruction efforts is that Halliburton is looting the treasury and that contractors in Iraq are overpaid profiteers. But those thousands of construction personnel build bases, roads, and Iraqi facilities, sometimes under fire, while living with the thought that shelling or shooting might break out any minute. I consider them more likely to be underpaid.

Other hardworking civilians include an astonishing number of Defense Intelligence Agency analysts, provincial reconstruction teams, investigators from the Pentagon, and midlevel diplomats constantly shuttling around Iraq. Even in the present calmer climate, their duties can pose higher risks than those of combatants because they hop from one area to another, in convoys and in aircraft, and are often taken to the front immediately on arrival. Many of them are courageous women who think nothing of jumping on a Black Hawk to copter up to Fallujah, tour the town, meet Iraqis, write reports, fly back, low and in pitch-black night on an Army helicopter, and then repeat the sequence the next day.

This is not a poor country. Flying over the Tigris-Euphrates valley (I speak now as a farmer) you see a land unlike anything in Kuwait or Saudi Arabia. The soil is rich, the water plentiful, and the dry climate perfect for intensive agriculture. That the country, in theory, could pump well over 3 million barrels of petroleum a day within a year or two gives some indication of just how badly Iraq has been run during the past forty years. Whatever this is, it is not a “blood for oil” war, more like “billions in aid for a region with its own $80-a-barrel oil.” We are stealing no one’s petroleum but rather trying to secure a naturally rich country to allow its inhabitants to profit from it. (The Chinese may soon have a concession; one wonders whether Al-Qaeda will go after them—and whether critics on the Left will cry, “No blood for Chinese oil.”)

We are using all of our twenty-first-century capability, money, education, and experience to fathom what is going on in the minds of millions of Iraqis—lost pride, a ruined country, thirty years of abject suffering—and to figure out to what degree they can channel their honor, status, and pride not into insurgency but into rebuilding their own country. It is a delicate balance.

In fact, it seems the task of a surgeon of diplomacy, this prodding of the Iraqis to step forward, without creating either dependency on outside assistance or a sense of abandonment by America. Few back in the States could pull it off.

One example: the tribal sheiks are coming forward to offer support against Al-Qaeda, in a movement centered on what has been called the “Anbar Awakening,” but they cannot run a government or supersede provincial administrations and the rule of law. So how do you encourage their quasi-vigilante efforts and self-help militias while delicately reassuring officials that these grassroots efforts will be incorporated into government—an entity that many not only distrust but recently attempted to demolish?

AL-QAEDA AND ITS HYPOCRISY

The abject irreligious nature of Al-Qaeda is a theme I heard again and again from analysts and intelligence officers. It is not religious zealotry to cut off the fingers of smokers, as the self-styled jihadists do, take 14-year-old “brides,” mutilate the dead, demand that bodies remain unburied, and steal businesses, homes, and cars—all verifiable incidents. We think of bin Ladenism as a distortion of Islam, but on the street level it is a cover for gasoline and food racketeering, petty theft, and murder. Soldiers spoke of confiscated Al-Qaeda computers with the worst sort of pornography on them and stories by Iraqis of known deviants, thugs, and criminals now masquerading as jihadists.

Here we prove incompetent by not publicizing the nature of hard-core jihadists, not just their hypocrisy and brutality but their criminality. No doubt many of the 100,000 felons Saddam released on the eve of the war ended up working for Al-Qaeda, a fact we again have blithely forgotten.

How can we be doing so much in so many areas but almost nothing to bring to the world’s attention the abject fraud of Al-Qaedism? We are at war not just with radical Islam but with the dregs of humanity, a sort of updated SS. They are criminals first, pseudo-fundamentalists second—a sort of Islamic front for Mafia-like extortionists and killers.

INTELLECTUAL FIREPOWER

John Kerry once quipped, “You know, education—if you make the most of it—you study hard, you do your homework and you make an effort to be smart, you can do well. If you don’t, you get stuck in Iraq.” But perhaps we should amend that to “if you get educated, you serve in Iraq.”

Among the small circle I met or corresponded with there, Colonels William Rapp, Christopher Gibson, and H. R. McMaster have doctorates, as does General David Petraeus and scores of others I met. I don’t mean to suggest that PhDs are smarter (some of the stupidest people I’ve ever met have doctorates), only that the military puts a high emphasis on continuing education and original research, especially valuable in a complex, if not bewildering, theater like contemporary Iraq.

So it is not uncommon to be in a forward operating base and meet someone who taught at the Naval Academy or West Point, or whom one has met at an academic conference, or who had written a journal article one has read, interweaving stories about a recent attack with a discussion of academic bibliography.

Three weeks after I heard a formal lecture on the history of Vietnam presented by McMaster, a Hoover research fellow, at Hillsdale College, I found myself being led by him in full combat gear through Anbar. Similarly, in the spring I spoke often at the Hoover Institution with Gibson, who was a national security affairs fellow, about his soon-to-be published book on military command; I saw him in Baqubah, where he is serving his fourth tour of duty in Iraq (his first was a stint during the Persian Gulf War).

I learned a great deal about Iraqi topography from Major Joel Rayburn after we coptered over the desert—no surprise, since he is writing his doctoral thesis on the British experience in Iraq. Camp Victory, the U.S. headquarters in Baghdad, has dozens of PhDs, who see combat often, and MAs in everything from Arabic and Islamic studies to military history.

In short, we might amend Kerry’s comment further to say that the brighter one is, it seems, the likelier she or he is to be in Iraq.

AN AMERICAN LEADERSHIP MODEL

One result of General Petraeus’s appointment seems to be a constant reappraisal by officers of almost everything we are doing. They speak freely about our prognoses, what we are doing right, what wrong; some are more glum than others. I met a few who were pessimistic and blunt about the outlook, who said Iraqis were perfidious and hopeless and the effort impossible. They were in a clear minority. But even the pessimists were encouraged to speak out rather than being dubbed defeatist and silenced. (Try speaking out in a similar fashion on campus, or inviting a Larry Summers to lecture.)

This is really a war to be won or lost by middle-echelon officers—majors up to full colonels—who, like Roman proconsular officials, must work alongside Iraqis to reorganize provinces as big as large American states. These capable Army and Marine officers seem to have been instrumental in bringing about the Anbar Awakening. Often, with almost no time for reflection or guidance, they have had to make critical decisions such as whether to enlist Sunnis into the security services—and often their decisions have been right.

U.S. officers wear almost identical camouflage. It is very hard to detect rank; only a small black insignia sewn at the breast indicates status. I note that in contrast with the university, U.S. officers seem much less concerned with rank: not a single officer reminded me that he or she had an advanced degree from a blue-chip school—an unsolicited offering common on campus. (The university is a natural comparison, since much of the antiwar sentiment emanates from it, and invites an obvious contrast about the relative degree of diversity, privilege, competence, and free speech.)

Iraqi officers are trying to adopt much of the ethos of the American officer corps, although there remain cultural and other differences. Iraqi officers with the rank of colonel and above insist on tea being served to them and keep a retinue of hangers-on who give constant obeisance; American officers more often open the fridge and offer you water themselves. Another ubiquitous contrast: in every Iraqi conversation, the Sunni/Shiite divide comes up. But on the American side, religious and ethnic designations— Mexican-American, African-American, Asian-American, so-called white— mean nothing. In this regard, our military does a far better job with diversity than the hothouse university, where difference is artificially emphasized, often for personal advantage. On the front lines, it is incidental to identity, not essential—something that amazes Iraqis, who sometimes seem puzzled about what constitutes an “average” American.

Iraqi military leaders are constantly coached to get out into the field, risk danger, and treat their subordinates with respect. Many are doing just that, to such a degree that entire units are beginning to emerge that are probably better than any in the Arab Middle East. Surely one fear of Iraq’s neighbors is that, if this country ever settles down, its army will be one of the most professional and competent in the region.

IRAN AND THE SHIITES

The Iranians are on everyone’s mind, especially in the Sunni-majority provinces. What is to be done with Basra (perhaps nothing, since the Iraqi- Shiite government will have to deal with its own militias to keep the city functioning)? What to do with Iranian super-IEDs (precisely machined explosive devices, with copper plates that nearly liquefy on detonation and, then in slug form, can penetrate all our existing armor, resulting in horrific wounds)? What to do with hacks in the government who are taking money and orders from Tehran? Yet the last thing U.S. officers wish is a war with Iran, a conflict that would immediately jeopardize everything they have achieved since spring. They express a desire for tougher sanctions, perhaps an embargo if Iranian enrichment cannot be stopped, to squeeze Iran enough to stop sending its agents and weapons to kill Americans but without galvanizing the Shiites into a surrogate Iranian army.

A shooting war with Iran, if it widened to include ground operations, would lead to a civil war in Iraq with clearly defined sides, large armies, and full-scale battle, rather than the current sectarian bloodletting. Something to watch for: if our success continues, the Iranians will become desperate to stop it. Only our being “bogged down” in Iraq, so they think, stops their own rendezvous with the Americans.

Most of the U.S. officers and their soldiers I met also believed we could win in Iraq—that we are winning—but most qualified that optimism: the Iraqis will have to step forward much more rapidly and competently, especially those in the Shiite-dominated Ministry of Interior, to translate newfound grassroots political and military participation into institutional stable government.

The subtext of all conversations with Americans and (mostly) Sunni Iraqis was how, with Saddam’s removal, we had turned the country upside down, in typically radical American fashion. After the U.S. invasion, the once-despised Shiites, many having no education or experience outside Iraq, found themselves running the country, while the 2 million Sunnis who used to manage things were exiles—a sort of justice, but one that immediately posed myriad practical problems.

So we ask of the Shiites instant experience, learning, skill, magnanimity, and forgetfulness of past abuse as they take up the reins of government; that they include the Sunnis; and that they give Anbar and Diyala provinces their fair share of revenues—all while stopping the flow of Iranian weapons. If they should accomplish this mission, the surge of money and work would keep the youth out of Al-Qaeda and too busy to resume attacks on Americans. That’s a simplification, but more or less a common sentiment of Sunni Iraqi provincial officials.

It is absolutely not true that the American military cannot define victory. Military leaders can and do all the time. It is the creation of a stable state that enjoys something of the calm of a gulf monarchy—but without the monarchial authoritarianism or the sharia law as implemented by Saudi Arabia. In other words, they hope for something like a Kurdistan or Turkey, and believe that the oil and agricultural wealth of Iraq, and its experience with secular traditions, might make that possible.

Further, many of the most thoughtful majors and colonels defined the cost/benefit analysis not in terms of Iraq per se but in view of the entire region. A stable Iraq would pressure Iran, and stop being a quarter-centurylong petroleum nexus of terror and trouble for others.

WITH GENERAL PETRAEUS

I spoke for an hour with General Petraeus, along with Rich Lowry of the National Review, at Camp Victory. I found the general at times soft-spoken, gruff but polite, blunt, candid, informed, and generous with his time and praise of his subordinates. He is a colonel’s general, and represents the military’s efforts to establish a brain trust here—to bring in those with advanced degrees, who question the status quo, and who find that their intellectual skills and education are nearly as important as their military acumen in finding a way through this labyrinth.

He is not prone to misstatement or bluster or partisanship and would seem a natural leader whom the Democrats could rally behind as well (while taking undue credit for demanding the changes that led to his appointment). So the tactic of slandering him, as we saw in September with the MoveOn.org “Be-tray-us” ads, is nothing short of political suicide for the Democrats—which those who finally distanced themselves from their in-house zealots learned belatedly. But that was a mere sideshow. The real task: can the Iraqi violence be stopped to allow reconciliation?

Petraeus is trying to reconcile two widely divergent views. His commanders in the Sunni provinces warn that the good news of calm is tenuous, dependent on good-faith efforts by the Shiite government to allot a fair measure of money to these minority constituencies that have sheltered both Al-Qaeda and former Baathists. Meanwhile, he agrees that hypercriticism of the elected Shiite government for its spite and intransigence can be counterproductive, creating only resentment—especially because it is almost impossible to separate deliberate, malicious acts within the ministries from simple incompetence. An elected government, after all, is sovereign, and we work with those elected by a plurality of Iraqi voters.

Thus, one must constantly pressure, coax, and argue for a Sunni constituency that until very recently was trying to blow apart one’s own troops. We liberated the Shiites, found them allies against Al-Qaeda and Baathists, and now worry more about them than we do the Sunnis who killed U.S. soldiers far more frequently for the first four years.

Iran also came up in our conversation. I gathered from Petraeus that we have to find a way to stop Iranian infiltration and its direct weapons deliveries, perhaps at first by moving our military compounds closer to the border and getting Iraqis to monitor the intrusions along with us. We must also get the Europeans to curb trade and investment; that alone would cripple the theocracy. What we must be careful about are direct strikes against Iranian weapons facilities that would only prompt a terrorist response—or worse—in Iraq at this most critical juncture.

So how does one balance that act—wean the Shiites of Iranian help, have the government rein in the Iranian-backed militias, and convince Baghdad that the new Sunni protection forces are no threat to the government?

BOMBS AND ARBITRARY DEATH

Colonel James Hickey gave a scholarly presentation about IEDs—frightful weapons that kill randomly, without recourse, and instill a sense of dread among those forced to drive over highways deceptively free of danger.

I won’t go into detail, but the possible solutions are not merely technological, given that we are in a constant challenge/response cycle with sophisticated enemies, in which deadlier mines can gain an edge in much less time than it takes to develop a far more expensively armored vehicle or jamming device. Even the new wedge-bottom military vehicles—I rode in a MRAP, or Mine Resistant Ambush Protected vehicle, and found that it seemed to ride much more cumbersomely than the “up-armored” Humvee—are vulnerable to Iranian-machined copper-headed IEDs, as are at times even Abrams tanks. All the jamming gear and armor plate in the world can’t fully protect our soldiers driving down roads mined with Iranian or Al-Qaeda bombs. (In Washington in late October, the Defense Department brought together some 750 experts from academia, science, and the military to tackle the IED problem. Retired General John Abizaid, former head of the U.S. Central Command and now a Hoover distinguished visiting fellow, said in his keynote speech to the conference that such efforts may reduce the IED danger but are unlikely to make it entirely disappear.)

So the answers lie in intelligence, and that means getting the local population to identify the bomb makers, those who plant them, the houses where the bombers sleep, and the places where they eat. I think we are winning that race, but the rub is that an exasperated American public has little tolerance for further casualties, a fact well known to the enemy. So to maintain our pressure on Al-Qaeda we must suffer almost no losses, which means almost no IED casualties. Even the best analysts can’t promise that.

Soldiers die in Iraq in unexpected ways, as is true in all wars. But the line from rear to front is blurred to an astonishing degree. The enemy has no uniforms, and we sometimes know very little about shifting alliances—and who is who on any given week. Shrapnel can fly at any second into a hospital tent in the massive Balad military base, the work of a single terrorist. With so many poorly trained Iraqis with so many guns, accidental shootings are common. Paid insurgents can fire a mortar shell into, and drive away from, even the most fortified target. Listening to the stories of how our 3,800 casualties have died, I was struck by how often death came in moments that were outside “combat” and involved simply driving, sleeping, or eating dinner.

Here is a small example of what must be an everyday occurrence. After one visits areas in Anbar with active hostilities, the ten-mile drive from Camp Victory to the tarmac at the Baghdad airport seems to pose little danger. But when my group of six (journalist Lowry, two National Guard lieutenants, and two Air Guard pilots) arrived at the runway about 7:30 p.m. and approached our light prop plane, a mortar round landed with no warning thirty yards from us. We dived to the ground.

All that saved us was that instead of immediately exploding and showering us with shrapnel, the round hit the concrete obliquely and skipped before exploding at a safer distance. The entire airport was shut down for a considerable time after the attack. When it reopened, we walked over to where the round had hit the tarmac and saw that even without going off immediately, the round, if aimed just a few yards differently, would have taken out at least one of us. So one of the supposedly safest places in Iraq on any given evening can prove to be one of the most dangerous.

To stave off defeat, the insurgents, whether ex-Baathists, Al-Qaeda fighters, or Shiite militias, are embedded within terrorized communities. And they know that although a firefight with a U.S. Marine or Army unit means instant death, an occasional quick rocket or mortar salvo might randomly kill an American—and with that death comes another headline in a U.S. newspaper and another thousand or more U.S. citizens sick of Iraq, the war, and Iraqis. The war has increasingly become defined only on the basis of how many of our own die, and that’s a measurement the enemy welcomes. The enemy’s only truly effective weapon is terror, which brings with it demoralization and fear.

I hope to make a third visit to the front this year, to see to what degree the Anbar Awakening has taken hold and resulted in an institutionalized stability. If the Sunni transformation continues, this historic development may well tip the scales in our favor—with enormous political ramifications throughout the region, and indeed the world. How the Arab world—or indeed the American Left—will handle scenes of former enemy and hardcore Sunni nationalists working side by side with Americans I don’t quite know. But it should be interesting.