- Budget & Spending

- Economics

- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

- US Labor Market

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Science & Technology

- Energy & Environment

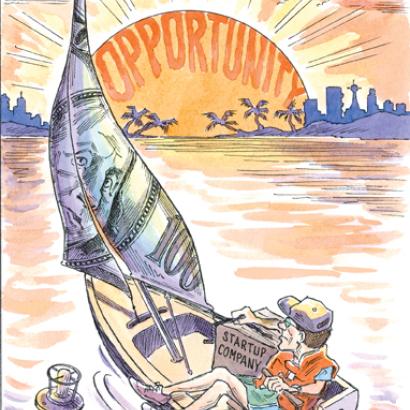

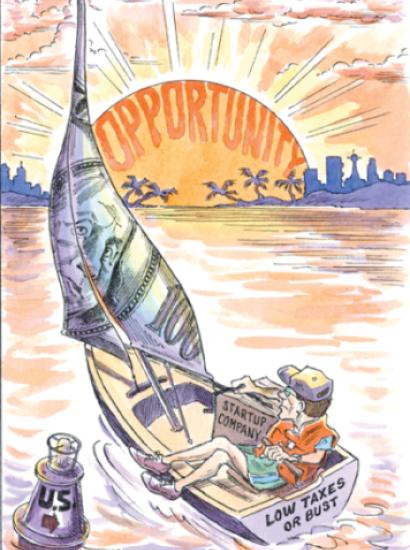

The other day a friend of mine (we’ll call him Doc) had to cut short a telephone conversation. “Gotta run,” he said. “The government of Singapore just arrived.”

Although the entire government of Singapore hadn’t actually trooped into Doc’s Northern California office, I learned, when we spoke again, that the delegation had been substantial. The reason for the visit? A recent Obama tax proposal (since put on the back burner, but still simmering).

Here the story gets a little complicated. But bear with me. The complexity is part of the point.

Doc helps run a company that has developed a new pharmaceutical technology. The technology remains confidential but can be thought of as a way of making many kinds of drugs more effective. After almost a decade of research and testing, Doc’s company is finally ready to bring the technology to market. Always tiny, the company is about to grow big.

Previously concerned only with treating sick people, Doc has lately found himself forced to study up on corporate tax rates.

What has he learned? That the United States imposes one of the two or three highest corporate tax rates on the planet. “If you take the federal rate of 35 percent, then add the average state rate, you come up with a combined corporate tax rate of about 39 percent,” Doc says. “In most other countries in the developed world, the corporate tax rate is in the 20s.”

During visits to Switzerland (several of the giant pharmaceutical companies with headquarters in Geneva are considering investing in his company), Doc has learned of even lower corporate tax rates. “In the canton of Zug,” Doc says, “the corporate rate is about 19 percent. But if you sit down with tax officials in Zug and tell them you’re torn between locating in Zug and locating in a different canton, maybe Vaud or Zürich, the chances are good that the officials in Zug will cut you a deal—something like a 10 percent rate for a decade.”

Variations in corporate tax rates from one country command the attention of all international corporations, of course. But in pharmaceutical corporations, such variations prove crucial.

“Only a small portion of the revenue stream in a company like ours goes toward the direct costs of product,” Doc explains. “The rest—often as much as 90 percent—represents the value of the patents and other intellectual property.

“If we locate the entity that owns our patents here in the United States, then we’ll be taxed at a rate of 39 percent on all our revenue. But if we locate the entity that owns our patents outside this country, we’ll take a much smaller hit on the income we derive from the intellectual property we created; again, that will represent most of our income.”

If Doc’s company collected $100 million in licensing fees here in the United States, for instance, it would be able to keep only about $60 million. If the company collected the same $100 million in Zug, Switzerland, it would be able to keep as much as $90 million.

“Once you look into it,” Doc says, “this isn’t rocket science.”

Enter the delegation from Singapore. “What the Singaporeans understand,” Doc explains, “is that one thing leads to another. Once you domicile your intellectual property offshore, it isn’t long before your manufacturing operations follow.”

Suppose, for instance, that for several years Doc’s company collected revenues for the use of its intellectual property at a site outside the United States. Now suppose that Doc’s company wanted to build a new fabrication plant. “We might want to build it here in California,” Doc says, “but how could we? All our money would be overseas. The moment we repatriated the money, we’d be taxed at the higher American corporate tax rate. What would we do? We’d find a manufacturing site outside this country.”

The delegation from Singapore hardly needed to explain this to Doc, but it did anyway: Singapore combines a corporate tax rate of less than half that of the United States with easy access to low-cost manufacturing in Malaysia, Indonesia, and China.

Which brings us, at last, to President Obama’s tax proposal. Although said to have been shelved last fall, it could come back to life as the administration hunts for ways to pay for costly changes in health care.

The idea is to change current law under which American corporations pay the U.S. corporate taxes only on income they repatriate to the United States. Under the administration proposal, American corporations would pay U.S. corporate taxes on all their income abroad, whether or not they repatriated it.

“Instead of making it easier to repatriate profits to this country,” Doc says, “Obama wants to make it almost impossible.”

The result?

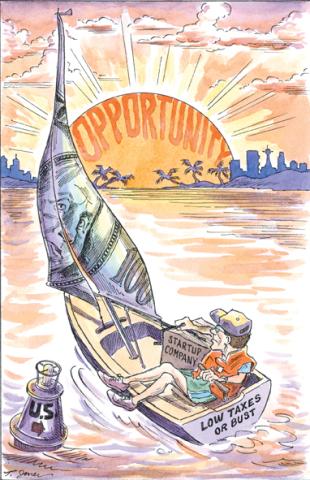

No longer are companies merely considering locating patents and manufacturing operations overseas. Now they have begun considering a more fundamental transformation: American companies with foreign operations are drawing up plans to turn themselves into foreign companies with American operations. Even as the president feigns concern over the high rate of unemployment, his tax policy is driving corporations—and the jobs they create—out of the country.

“This is just nuts,” Doc says.

Instead of attempting to extend the reach of the country’s exorbitant corporate tax rate, Obama should take a lesson from those local officials in Zug, Switzerland, and the delegation from Singapore. He should recognize that the global marketplace in tax rates has become just as dynamic as the global markets in oil, grain, and textiles. He should admit that the United States must compete—and that the only way for the nation to do so is to cut its corporate tax rate. Not trim it. Cut it.

“Corporate tax rates are too complicated to reduce to a sound bite for television,” Doc continues. “But do corporate tax rates matter? Well, let me put it this way. I wasn’t the only entrepreneur in Silicon Valley who agreed to an appointment with the delegation from Singapore.”