- Campaigns & Elections

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

The role of race in American politics cannot be understood except as an example of the role of ethnicity in American politics. Despite the long-standing elite opinion that ethnicity should not play any role in politics, that voters and politicians should act without regard to ethnic factors, in fact ethnicity has always played an important part in our politics. This is what we should expect in a country that has always had forms of racial and ethnic discrimination, and in which civic and university and corporate elites, for all their tut-tutting about ethnic politics, have often been more hearty practitioners than ordinary people of ethnic discrimination—of anti-Jewish discrimination up through the 1960s and of racial quotas and preferences since the 1970s.

Over the long course of our history, politics has more often divided Americans along cultural than along economic lines—along lines of region, race, ethnicity, religion, and personal values. This is natural in a country that has almost always been economically successful and culturally multivarious, in which economic upward mobility has been the common experience and in which cultural and ethnic identities have often been lasting and tenacious. During the 2000 presidential campaign it was noted by none less than Al Gore that we are moving into a new and unprecedented era in American history in which our people are being transformed from one to many. But Mr. Gore, in doing so, not only mistranslated the national motto e pluribus unum but also ignored the long history of American political divisions along racial and ethnic lines. We are not in a totally new place; we have been here before, and we can learn from our history—and our motto.

|

|

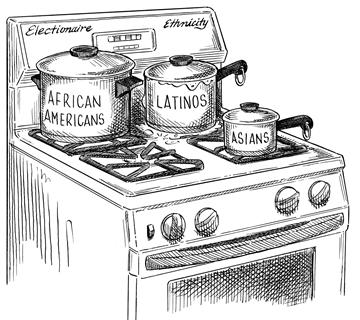

Illustration by Taylor Jones for the Hoover Digest. |

The common pattern seems to be this: there is an inrush into the electorate of a new ethnic or racial group, with a strong preference for one political party, and politics seems to be structured around this division. Attempts are made to limit the new group’s strength in the electorate, sometimes successfully, more often not. Then there are inrushes of other groups, with checkerboard political preferences, depending more on local circumstances and issues than on any single national pattern. Politicians and parties compete for the support of these groups, with generally benign results. Eventually there is regression to the mean: the issues and identities that once led a group to favor one party heavily are replaced by other issues and identities that tend to divide them pretty much along the lines of the electorate generally. But this is a process that can take a long time and one in which the original identities and issues continue to play an important role in politics for many years.

The Postwar Inrush of the "New Minorities"

At the time of Pearl Harbor, America seemed to have reached a pause in its racial and ethnic politics. But only a pause. For in the second half of the century, new groups entered the electorate, the groups that are now officially recognized as "minorities"—blacks, Hispanics, and Asians. On the surface, this seems to have produced an altogether new "multicultural" politics, as predicted by Al Gore among others. Some analysts proclaim with relish that white non-Hispanics will some time in the next century cease to be a majority and that "people of color" will control American politics. But on closer examination, these new inrushes of voters have produced an ethnic politics closely, almost eerily, resembling the ethnic politics of 100 years ago. And the results are likely to be similar: one constituency remaining solidly Democratic for years, others the subject of benign competition between the parties and ultimately regression to the mean.

First came the inrush of blacks into the electorate between 1940 and 1970. It was caused first by the huge migration of blacks from the rural South to the cities of the North and then by the end of the disenfranchisement of blacks in the South after passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965. Before 1940, there was relatively little migration of blacks to the North. But the war industries of the 1940s and the booming auto and steel factories of the 1950s and 1960s, whose unions strongly opposed racial discrimination, brought blacks north: the percentage of blacks living in the North rose from 23 percent in 1940 to 47 percent in 1970. At that point, migration leveled off. But for three decades the black move northward was one of the great migrations of American history.

|

The inrush of new minority voters over the last several decades has produced an ethnic politics that closely—indeed, almost eerily—resembles the ethnic politics of a century ago. |

These northward-moving blacks became the most heavily Democratic constituency in the nation—perhaps even more Democratic than the Irish of the nineteenth century at their most monopartisan. The Democratic percentage among blacks throughout the North rose to around 90 percent when President Kennedy backed the civil rights bill in 1963 and when the Republican Party’s presidential nominee, Barry Goldwater, voted against it in 1964. Since then, blacks have enthusiastically supported the national Democrats’ antipoverty and big-government programs. They have strongly supported race quotas and preferences. They gave overwhelming percentages to Jimmy Carter, Walter Mondale, Michael Dukakis, Bill Clinton, and Al Gore and almost unanimously supported Clinton against charges of scandal in 1998. For the last third of the twentieth century, they have been the solid core of the Democratic Party.

Then the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965 suddenly swept away all barriers against blacks voting in the South. Blacks rose from about 6 percent of the electorate in 1964 to 10 percent in 1968. But this did not have entirely positive effects for the Democrats, for in the same years, white Catholic voters were moving toward the Republicans. And in the meantime, southern white voters were moving rapidly away from the Democratic Party.

The Voting Rights Act was not the only 1965 law that changed the shape of the American electorate: so did the Immigration Act of 1965, in ways that were almost entirely unforeseen. Many in Congress voting for it may have expected a resumption of the European immigration so sharply cut off in 1924. But postwar Europe was prosperous and sent few immigrants. Instead they mostly came from Latin America and Asia. Latin America accounted for 40 percent of immigrants in 1971–80 and 39 percent in 1981–93; Asia (including the Middle East), for 36 percent in 1971–80 and 27 percent in 1981–93.

Like the immigrant groups that followed the solidly Democratic Irish from the 1850s to the 1920s, these new Hispanic and Asian groups did not flock almost unanimously as "people of color" to the Democratic Party but produced a checkerboard pattern of political allegiances. Hispanics and Asians have not necessarily seen discrimination as their greatest problem and have not seen big government as their greatest friend; for them America has been not an oppressor but a haven. And some liberal policies have arguably worked against their interests. Poor public education and bilingual education programs that prevent children from learning how to speak, read, and write English well have arguably hurt Hispanics; racial quotas and preferences have clearly hurt Asians. It simply does not make sense to see today’s Hispanics and Asians as the counterparts of blacks during the civil rights revolution. Certainly their political behavior is different. Blacks remain heavily Democratic, but the picture is quite different among Hispanics and Asians. Hispanics on balance currently lean Democratic but not everywhere and by differing margins and for different reasons in different places. Asians have actually been trending Republican.

Blacks: Solidly Democratic

Today’s blacks, like the Irish of 100 years ago, have a history that gives them reason to doubt the legitimacy of the demands of the larger society—slavery and segregation in one case, anti-Catholic laws in the other. Like the Irish of 1900, the blacks of 2000 are concentrated heavily in ghettoized neighborhoods of big cities; even in the South, heavily black rural communities have continued to lose population, and an increasing percentage of southern blacks live in the region’s burgeoning metropolitan areas.

This has been reflected in political representation. In 1990s redistricting, the Voting Rights Act has been interpreted as requiring the maximization of the number of majority-black districts, resulting in many convoluted district lines and a sharp increase in the number of black members of Congress and state legislators. However, such districting also reduces the number of blacks in adjacent districts and so arguably reduces the number of members of Congress with an incentive to pay heed to black voters’ opinions. It also means that most successful black politicians fall on the far left of the Democratic Party, a comfortable place in majority-black constituencies but not a good position from which to seek statewide or national office; it is significant that the first black to lead in presidential polls was not Jesse Jackson, who rose through protest politics, but Colin Powell, who rose through the most integrated segment of American society, the United States Army.

The blacks of 2000, like the Irish of 1900, have had high rates of crime and substance abuse; they have also produced large numbers of police officers and an influential clergy. They have produced many great athletes and entertainers and a cultural style that most Americans find attractive. They have tended not to perform well in economic markets, but they have shown an affinity for rising in hierarchies, particularly the public sector and electoral politics. And of course blacks in 2000, like the Irish in 1900, are one of the main core constituencies of the Democratic Party, although blacks are still awaiting, as the Irish were a century ago, their Al Smith and John F. Kennedy.

The blacks of 2000, like the Irish of 1900, show no sign of abandoning their overwhelming allegiance to the Democratic Party. Republican percentages among blacks have risen in the last two decades but only very slightly, except for a few unusual elections in a few states.

Hispanics: Leaning Left

Today’s Hispanics, like the Italians of 1900, come from societies with traditions of ineffective centralism, in which neither public nor private institutions can be trusted to act fairly or impartially. Like the Italians, the Hispanics have migrated vast distances geographically and psychologically, moving from isolated and backward farming villages to particular city neighborhoods pioneered by relatives and neighbors from home. The Hispanics of 2000, like the Italians of 1900, tend to be concentrated in only a few states: more than three-quarters of Hispanics live in California, Texas, New York, Florida, and Illinois.

Here they often maintain contact with their old homes, sending back remittances and in many cases returning: their commitment to remaining in the United States is in many cases not total. They often have strongreligious faith, but they tend to mistrust most institutions, including government and businesses. They depend on family and hard work to make their way.

|

The United States has a long history of political divides along ethnic lines. The phenomenon can be benign—and is as American as apple pie. |

Politically, the Hispanics of 2000, like the Italians of 1900, tend to vote for different parties in different cities. Cubans in Miami are heavily Republican, Puerto Ricans in New York heavily Democratic. There are rivalries as well within cities between different Hispanic groups.

Most important are the sharp differences between the politics of Latinos in the two most populous states, Texas and California. Mexican Americans in Texas, some of whom have deep roots in local communities and churches, elect Republican and conservative Democratic members of Congress and legislators as often as liberal Democrats and in 1998 polls were shown casting majorities for Republican governor George W. Bush. The pro-Bush feeling can be attributed to his fluent Spanish, his frequent visits to Hispanic communities, his policy of close ties with Mexico, his emphasis on family and hard work—his showing that he understands and appreciates the Latinos’ strengths. It also may rest on the fact that relations between Anglos and Latinos in Texas, for all its past history, have been relatively close and friendly: almost nobody doubts that Latinos are truly Texans.

In contrast, Mexican Americans in California often seem to live in a nation apart and are met with a certain hostility by Anglo elites, from the leftish Jews of Los Angeles’s west side to the rightish whites living in gated communities in the outer edges of metro L.A. to San Diego surfers worried about the discharges of Tijuana’s sewage on their beaches. California’s Latinos tend to live in enormous swaths of metro L.A., which until very recently had few Latinos, in atomized local communities where politics is waged by direct mail financed by rich liberals. The candidates they elect tend to come from a small group of politically connected Latino left Democrats.

In addition, California Latinos were repelled by the 1994 campaign of Republican governor Pete Wilson and his support of Proposition 187, barring aid to illegal immigrants. What bothered them was less the substance of the issue (some 30 percent of Latinos voted for it) than the implication they saw in Wilson’s ads that immigrants were coming to California only to get on the welfare rolls. Wilson’s failure to appreciate the genuine strengths of California’s Latinos and, until 1998 at least, California Republicans’ apparent lack of interest in them have produced higher Democratic percentages among Latinos there in the late 1990s than in the middle 1980s—an ominous sign for national Republicans, since Latino turnout has been rising sharply, and without a sizable share of Latino votes a Republican presidential ticket will have trouble carrying California.

Asian Americans: Leaning Right

Finally, the Asian Americans of 2000 in many ways resemble the Jews of 1900. The Asians, like the Jews, come from places with ancient traditions of great learning and sophistication but with little experience with an independent civil society or a reliable rule of law. Like the Jews, many Asians in this century—overseas Chinese, Vietnamese, Koreans, and Muslims and Hindus in India and Pakistan—have been subject to persecutions and have had to make their way in the world amid grave dangers. They tend to excel at academic studies and have quickly earned many places at universities—and have been greeted by quotas that bar them despite their achievements. They have had great economic success and perform well in economic markets. Like the Jews, they tend to be concentrated in a few metropolitan areas.

Politically, the Asians have been taking a different route from the Jews. Few, aside from some campus activists, have been attracted to left-wing causes; some (the Japanese Americans in Hawaii) but not very many have been staunch organization Democrats. Asians with a history of anticommunism have voted mostly Republican: Koreans, Vietnamese, Taiwanese. Filipinos, mostly in low-income jobs and subject to discrimination by Americans for a century, have been heavily Democratic. The Asian trend toward Republicans in the 1990s has not been much studied and is a bit mysterious. Contributing to it may be the Los Angeles riots (in which the Los Angeles elite tended to portray the rioters as victims and the shop owners of Koreatown as oppressors) and the racial quotas and preferences that bar so many Asians from places in universities.

Conclusion

The experience of the immigrants of 100 years ago should give us at least cautious optimism about the future course of the minorities of today. The high rates of crime and substance abuse among the Irish receded after some time; crime rates and welfare dependency among blacks have experienced a sudden and sharp decline in the 1990s. The aversion to education and economic advancement of Italian Americans waned in time, and, despite the civic poverty of their homeland and the dire predictions of elites earlier in this century, the Italians have blended in well to American life; there is good reason to think the same will happen to today’s Latinos. The Jews, early in scaling the economic and academic heights, have seen discrimination and anti-Semitism diminish toward nothing; the Asians may find the barriers they face receding as well.

Politically, all these new Americans have the advantage of living in a society where there is a tremendous political penalty for shows of intolerance and ethnic discrimination, and in which both political parties have an incentive to seek their support. There will be times when ethnic conflicts in politics will be wrenching, but American history also teaches us that ethnic competition in politics can very often be benign and in any case is as American as apple pie (or pizza or tacos).