- Budget & Spending

- Economics

- Economic

- History

“Just as some species become extinct in nature, some new financing techniques may prove to be less successful than others.”

The remark was made to Congress in September by Anthony Ryan, assistant secretary of the Treasury. Only when we know the true magnitude of the current financial crisis will we be able fully to appreciate the significance of his words.

Analogies between finance and evolution are nothing new. “The survival of the fittest” is a phrase that aggressive traders like to use. “It’s Darwinian out there” is a stock utterance by hedge fund managers after an especially tough week. Back in November 2005, a conference hosted by the investment bank Goldman Sachs was titled “The Evolution of Excellence.”

Yet, as became clear at that gathering, when financial practitioners use such terms they seldom understand just how pertinent they are. A long-run historical analysis of the development of financial services, going all the way back to the days of Charles Darwin, strongly suggests that evolutionary forces are as much at work in the realm of money as they are in the natural world.

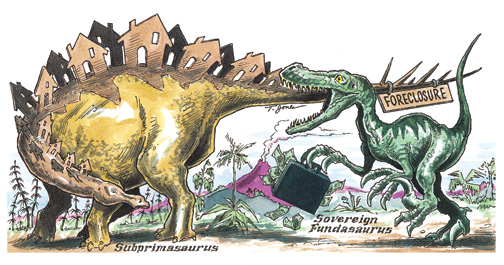

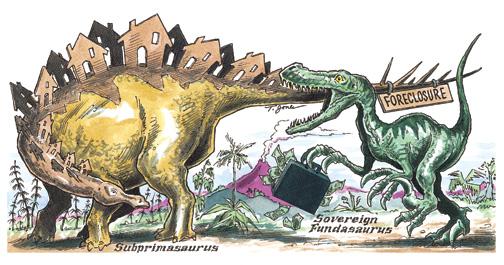

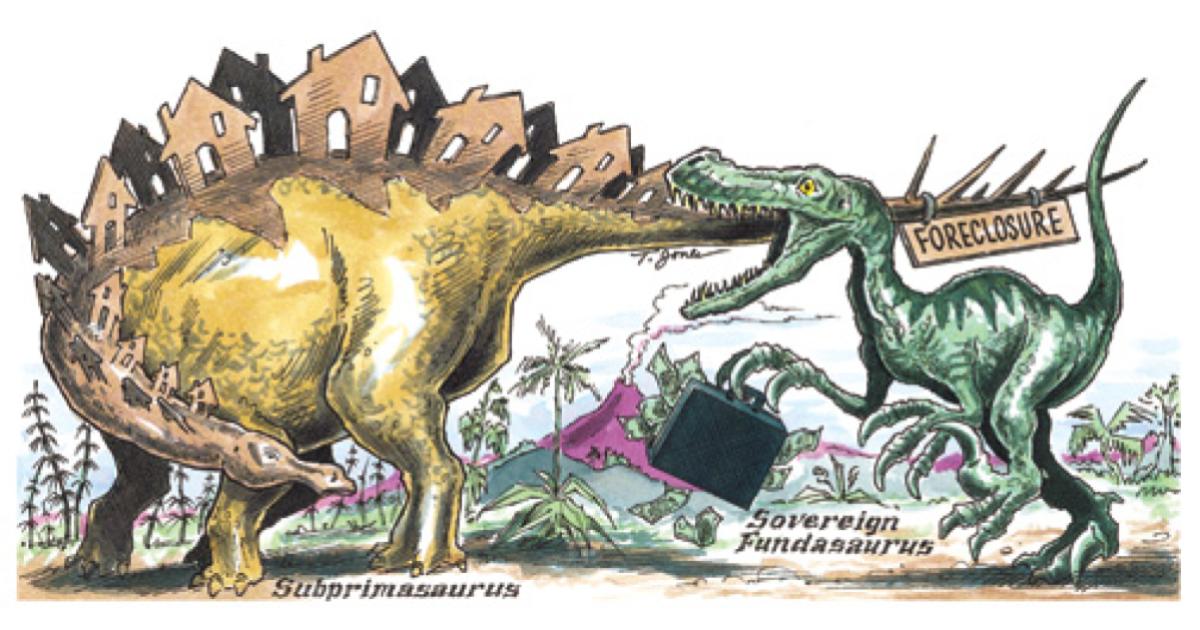

The big question for our time is: are we on the brink of a “great dying”— one of those mass extinctions of species that have occurred periodically in the history of life on earth, such as the Cretaceous-Tertiary crisis that killed off the dinosaurs? It is a scenario that many biologists fear, as human-caused climate change wreaks havoc with natural habitats around the globe. Financial analysts have their own great dying to worry about as another humanmade disaster, the subprime mortgage crisis, works its way through the global financial system.

THE ORIGIN OF FINANCIAL SPECIES

The notion that Darwinian processes may be at work in the economy was raised by Thorstein Veblen, the Norwegian-American economist best known for his Theory of the Leisure Class, as long ago as 1899. An academic journal has been devoted to the subject for the past 16 years, though most economists remain skeptical about the applicability of Darwin’s ideas to the economic sphere. The analogy is in fact surprisingly good in the case of the financial-services industry, which has many of the defining characteristics of a true evolutionary system:

- Genes, in the sense that certain business practices perform the same role as genes in biology, allowing information to be stored in the organizational memory and passed on from individual to individual or from company to company when a new one is created.

- The potential for spontaneous mutation, usually referred to in the economic world as innovation, and primarily, though by no means always, technological

- Competition among individuals within a species for resources, with the outcomes in terms of longevity and proliferation determining which business practices persist.

- A mechanism for natural selection through the market allocation of capital and human resources and the possibility of death in cases of underperformance—in other words, differential survival.

- Scope for speciation, sustaining biodiversity through the creation of wholly new species of financial institutions.

- Scope for extinction, with species dying out altogether.

Financial history is essentially the result of institutional mutation and natural selection. Random drift (innovations/mutations that are not promoted by natural selection, but just happen) and flow (innovations/mutations that are caused when, say, U.S. practices are adopted by Chinese banks) play a part. There can also be coevolution, when different financial species work and adapt together (like hedge funds and their prime brokers).

But market selection is the main driver. Financial organisms are in competition with one another for finite resources. At certain times and in certain places, certain species may become dominant. But innovations by competitor species, or the emergence of altogether new species, prevent any permanent hierarchy or monoculture from emerging. Broadly speaking, the law of the survival of the fittest applies. Institutions with a “selfish gene” that is good at self-replication (and selfperpetuation) will tend to endure and proliferate.

The analogy is, of course, not perfect. When one organism ingests another in the natural world, it is just eating, whereas in financial services, mergers and acquisitions can lead directly to mutation. Among financial organisms, there is no counterpart to the role of sexual reproduction. Most financial mutation is deliberate, conscious innovation rather than random change. Indeed, because a company can adapt within its own lifetime to change going on around it, financial evolution (like cultural evolution) may be best described not as Darwinian but as Lamarckian, after the French biologist who contended that an individual organism could acquire new and heritable traits. Still, the resemblances outnumber the differences—and evolution offers a better model for understanding financial change than any other we have.

Rudolf Hilferding, a German socialist, predicted a century ago an inexorable movement toward concentration of ownership in “financial capitalism.” The conventional view of financial development does indeed see the process from the vantage point of the big survivor. In the successful company’s official family tree, numerous small companies are seen to converge over time on a common trunk, the present-day conglomerate—the kind of giant “überbank” that Hilferding imagined would ultimately take over the entire financial system. This, however, is precisely the wrong way to think about financial evolution. Over the long run, financial innovation begins at a common trunk. Over time, the trunk branches outward as new kinds of banks and other financial institutions evolve. The fact that a particular institution successfully devours smaller rivals along the way is more or less irrelevant. In the evolutionary process, animals eat one another, but that is not the driving force behind evolutionary mutation and the emergence of new species and subspecies.

Economies of scale and scope are not always the driving force in financial history. More often, the real drivers are the process of speciation—when new types of companies are created—and the equally recurrent process of “creative destruction,” whereby weaker companies die out or, more commonly, get eaten.

Take the case of retail and commercial banking, where considerable “biodiversity” remains. North American and some European markets still have highly fragmented retail banking sectors. The cooperative banking sector has seen the most change, with high levels of consolidation (especially following the crisis of the 1980s surrounding the U.S. savings and loans industry) and most institutions moving to shareholder ownership. But the only species that is now close to extinction in developed countries is the stateowned bank, as privatization has swept the world.

In other respects, the story is one of speciation—the proliferation of new types of financial institutions—which is just what we would expect in a truly evolutionary system. Many new “monoline” financial services companies have emerged in commercial banking, especially in consumer finance (for example, Capital One). A number of new boutiques now exist to cater to the private banking market. Direct banking (by telephone and the Internet) is another relatively recent and growing phenomenon throughout the developed world.

Likewise, even as giants have formed in the realm of investment banking, new and nimbler species have evolved and proliferated. Although what many recognize as the first hedge fund was established as long ago as 1949, their emergence as big players in global financial markets is a relatively recent phenomenon. In 1992, there were just 400 hedge funds, with $50 billion in assets under management. By the end of 2006, the number had increased more than twentyfold and assets under management by a factor of nearly thirty. And by the second quarter of 2007, there were 9,767 such funds, with $1,740 billion under management.

Thanks to leverage, the estimated gross investments of the five largest funds amount to around $100 billion. Altogether, hedge funds now account for between one-third and one-half of all trading in the U.S. and British equity and bond markets.

Meanwhile, there has been a somewhat smaller surge in the number of private equity partnerships and the assets they manage, and the rapidly accruing hard currency reserves of exporters of manufactured goods and energy are producing a second generation of sovereign wealth funds.

Not only are new forms of financial institution proliferating; so too are new forms of financial assets and services. In recent years, investors’ appetites have grown dramatically for mortgage-backed and other assetbacked securities. The use of derivatives has also increased significantly. In evolutionary terms, then, the financial services sector appears to be in the midst of a kind of “Cambrian explosion,” with existing species flourishing and new species (such as hedge funds and private equity partnerships) increasing in number. Yes, there are giants such as Citigroup. But, as in the natural world, their existence does not preclude the evolution and continued existence of smaller species. Size is not everything, in finance as in nature.

Indeed, the very difficulties that arise as publicly owned companies become larger and more complex—the diseconomies of scale associated with bureaucracy, the pressures associated with quarterly reporting—make it probable that new kinds of private firms will proliferate. What matters in evolution is not your size or your complexity. All that matters is that you are good at surviving and passing on your genes. The financial equivalent of evolutionary success is being good at generating returns on equity and generating imitators employing a similar business model. Both are easier for small firms.

SHOCKS LEADING TO EXTINCTION

Mutation and speciation have usually been evolved responses to the environment and competition, with natural selection determining which new traits become widely disseminated. The evolutionary process, however, has been subject to recurrent exogenous disruptions in the form of geopolitical shocks, financial crises, and regulatory interventions (or lapses). The Great Depression of the 1930s and the great inflation of the 1970s stand out as times of major discontinuity, along with “mass extinctions” such as the bank panics during the 1930s and the savings and loan crisis in the 1980s.

Could something similar happen in our time? Certainly, the sharp change in credit conditions in the summer of 2007 created acute problems for some hedge fund strategies, leaving the funds vulnerable to redemptions by investors. But a more important feature of the recent credit crunch has been the pressure on banks.

More than $60 billion in write-downs has so far been acknowledged by the world’s leading banks, but it is widely assumed that as much as $300 billion of subprime-related losses will eventually come to light. Pressure is mounting on some banks to bring the assets of other novel organisms— conduits and strategic investment vehicles—back on to their balance sheets. Yet the difficulty of pricing these assets in highly illiquid markets and the need to maintain capital adequacy are making this easier to say than to do. In Europe, for example, average bank capital is now equivalent to less than 10 percent of assets, compared with around 25 percent toward the beginning of the twentieth century. Some banks must sooner or later choose between increasing their capital and restricting their lending.

And what of the market for mortgage-backed securities? Recent events have certainly checked the hopes of those who believed that the separation of risk origination and balance sheet management would distribute risk optimally throughout the financial system. The U.S. asset-backed issuance has collapsed since August, as has the issuance of collateralized debt obligations, another relatively novel financial life form.

Nevertheless, the problems of the banks are opportunities simultaneously for some big hedge funds, particularly those that seized the moment to go public when stock markets were buoyant, and for sovereign wealth funds, which are acquiring stakes in big-brand banks at what seem like bargain prices.

A REGULATED SYSTEM

There is, however, one big difference between nature and finance. Whereas evolution in biology takes place in the natural environment, where change is essentially random (hence Oxford biologist Richard Dawkins’s image of the blind watchmaker), evolution in financial services occurs within a regulatory framework, where—to borrow a phrase from anti-Darwinian creationists—“ intelligent design” plays a part.

Sudden changes to the regulatory environment are rather different from sudden changes in the macroeconomic environment, which resemble environmental shifts in the natural world. The difference is that there is an element of endogeneity in regulatory changes because those responsible are often “poachers turned gamekeepers,” with a good insight into the way that the private sector works. However, the net effect is the same as climate change in biological evolution. New rules and regulations can make previously good traits suddenly disadvantageous. The rise and fall of the savings and loans institutions, for example, was due in large measure to changes in the regulatory environment in the United States.

The primary focus of most financial regulators is to maintain stability within the sector, thereby protecting the consumers whom banks serve and the economy that the industry supports. Companies in nonfinancial industries are neither so fundamental to the economy nor so critical to the livelihood of the consumer. The collapse of a leading financial institution, in which retail customers lose their deposits, is an event that any regulator (and politician) wishes to avoid at all costs—a fact of which the British authorities were painfully reminded by the run last summer on Northern Rock, a mortgage bank.

An old question that has raised its head once again in recent months is how far implicit guarantees to bail out banks create a problem of “moral hazard,” encouraging excessive risk taking on the assumption that the state will intervene if an institution is considered too big to fail (meaning too politically sensitive or too likely to bring a lot of other companies down with it). From an evolutionary perspective, however, the problem looks slightly different. It is, in fact, undesirable to have any institutions in the category of “too big to fail” because, without occasional bouts of what Harvard economist Joseph Schumpeter termed creative destruction, the evolutionary process will be thwarted. Japan’s experience in the 1990s stands as a warning to legislators and regulators that an entire banking sector can become a kind of economic dead hand if institutions are propped up despite underperformance.

Every shock to the financial system must result in casualties. Left to itself, “natural selection” should work fast to eliminate the weakest institutions in the market, which typically are devoured by the successful. But most crises also usher in new rules, as legislators and regulators rush to stabilize the system and protect the consumer/voter. The critical point is that the possibility of extinction cannot and should not be removed by excessively precautionary regulation.

As Schumpeter wrote more than seventy years ago: “This economic system cannot do without the ultima ratio of the complete destruction of those existences which are irretrievably associated with the hopelessly unadapted.” Creative destruction, in his view, meant nothing less than the disappearance of “those firms which are unfit to live.”

The coming months will determine how far, in terms of economic impact, the current crisis is a true ice age as opposed to just a severe winter. It will also determine which among the world’s financial groups are the dinosaurs and which are the fittest mammals.