- History

- Military

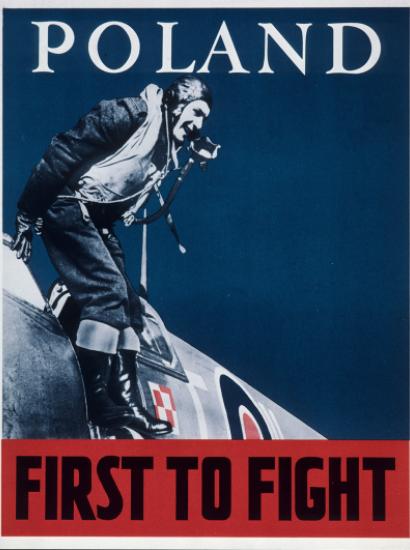

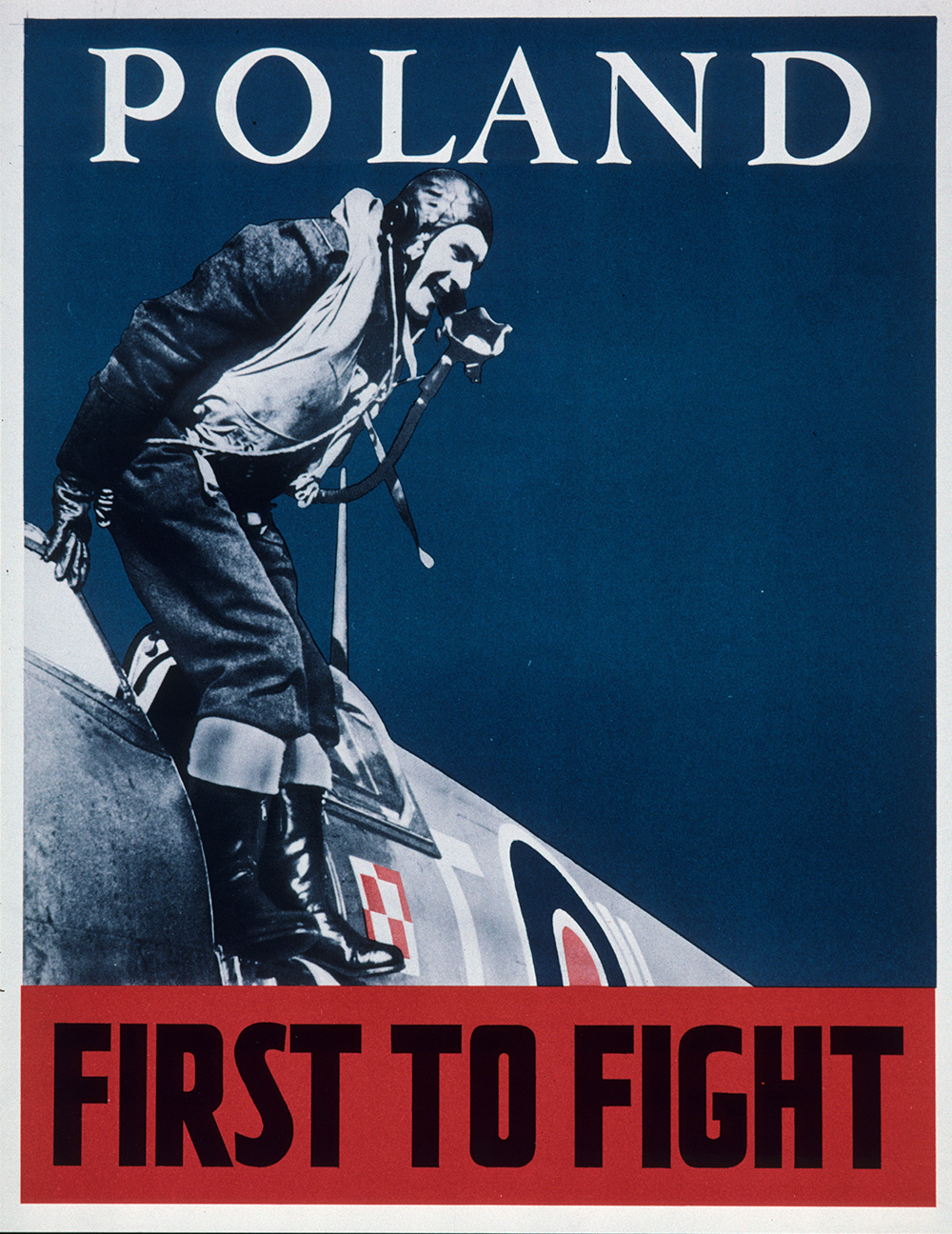

Eighty years ago this month the most catastrophic war in history broke out. On September 1, 1939, Nazi Germany invaded her neighbor, Poland. From before dawn German shells and bombs fell across the breadth and width of the country. Despite the obvious buildup of military forces on the other side of the frontier, the Poles had not fully mobilized because British and French statesmen worried that such a mobilization might encourage Hitler to go to war—as if he needed any encouragement. In every sense, the German invasion of Poland proved to be a disaster for Poland, a disaster exacerbated by the willful policies of appeasement that the British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain had fostered over the previous two and a half years.

Nevertheless, the Germans had also miscalculated in estimating the actions of the democracies and the potential for war. Hitler famously remarked in the spring of 1939 that he had seen his enemies at Munich and they were worms. That calculation certainly explains the enthusiasm with which he had ordered the Wehrmacht to occupy the remainder of the Czech state in March 1939. And in fact he had correctly calculated the response of Chamberlain and his fellow ministers, because their initial reaction was that nothing of significance had happened. But what Hitler had not calculated on was the reaction of the British people, who far better than their leaders understood that the Nazi occupation of Bohemia and Moravia had undermined the assumptions on which appeasement rested. The resulting fire storm of public opinion forced Chamberlain to guarantee Polish independence at the end of March 1939. His decision made sense in diplomatic terms; it certainly made sense in terms of Britain’s domestic politics. But it did not make any sense in strategic and military terms.

From March 1939 to the beginning of the war, the Chamberlain government pursued a policy of attempting to ignore the harsh strategic reality that Britain and her ally France were confronting an inevitable war against Nazi Germany. Admittedly, Britain did begin a serious effort of rearmament, but that effort largely aimed at persuading Hitler to back down. Ironically, British rearmament, which now was beginning far too late, only pushed the Führer to move before British efforts could have an impact. By early April, German military planning was in the process of working out the details involved in destroying the Polish state. Hitler had no intention of being robbed of his chance at war as had happened at the Munich Conference in September 1939.

Perhaps nothing better underlines the faulty assumptions on which the Chamberlain government approached the crisis of summer 1939 than the lackadaisical approach with which it approached Stalin and the Soviet Union. Clearly, British leaders believed the Soviets were of little or no importance in the emerging strategic calculus in which they believed war was not inevitable. The Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact of August 1939 was undoubtedly the shabbiest piece of diplomacy in a decade of dishonest dealings. And the peoples of the Soviet Union would pay a terrible price twenty-one months later. But for now, it allowed the Soviets to remain out of a war, while the capitalist powers supposedly destroyed themselves. It also allowed the Germans to escape the possibility of a two-front war, once they had destroyed the Polish state.

In addition to various other efforts to placate the Germans, the British offered a large loan, if the Germans would behave themselves. But it was for nought. On September 2, nearly forty hours after the Germans had begun killing Poles in large numbers, Chamberlain went before an expectant House to deliver a particularly mealy-mouthed speech. Furiously, Leo Amery, a leading Conservative, shouted to the Labour Party spokesman, Arthur Greenwood, “Speak for England, Arthur.” That night, as an angered House dispersed, the Conservative chief whip, David Margesson, warned the prime minister that if he did not have a declaration of war in hand when the House met the next day, he would face a major revolt among the back benchers. Chamberlain would have that declaration of war the next day, but it would take until May 10, 1940 when Winston Churchill became prime minister before the British people would possess a voice that would speak to their moral outrage at Hitler’s duplicitous, evil regime.

The lesson of history is sharply edged in the debacle of the late thirties. There are times when democracies and statesmen must face the harsh reality that there may be no alternative to war. Not to confront that reality is to make the conditions of an inevitable war that much less palatable and that much more costly.