- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- Security & Defense

- US Defense

- Terrorism

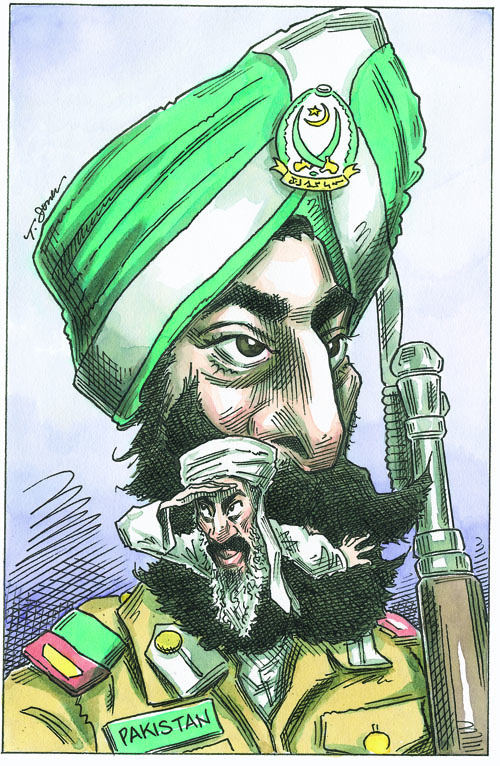

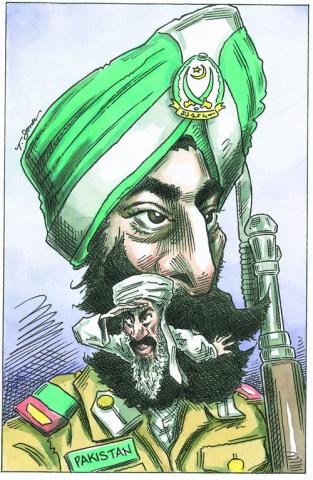

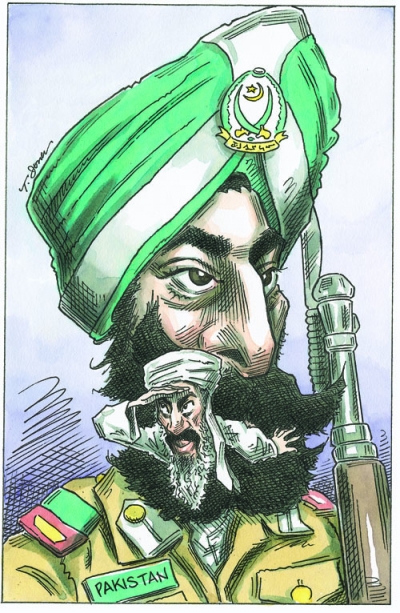

On September 22, 2011, Admiral Mike Mullen, then-chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, made his last official appearance before the Senate Armed Services Committee. In his speech, he bluntly criticized Pakistan, telling the committee that “extremist organizations serving as proxies for the government of Pakistan are attacking Afghan troops and civilians as well as U.S. soldiers.” The Haqqani network, he said, “is, in many ways, a strategic arm of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence Agency [ISI].” In 2011 alone, Mullen continued, the network had been responsible for a June attack on the Intercontinental Hotel in Kabul, a September truck-bomb attack in Wardak province that wounded seventy-seven U.S. soldiers, and a September attack on the U.S. embassy in Kabul.

These observations did not, however, lead Mullen to the obvious conclusion: Pakistan should be treated as a hostile power. And within days, military officials began walking back his remarks, claiming that Mullen had meant to say only that Islamabad gives broad support to the Haqqani network, not that it gives specific direction. Meanwhile, unnamed U.S. government officials asserted that he had overstated the case. Mullen’s testimony, for all the attention it received, did not signify a new U.S. strategy toward Pakistan.

Yet such a shift is badly needed. For decades, the United States has sought to buy Pakistani cooperation with aid: $20 billion worth since 9/11 alone. This money has been matched with plenty of praise from U.S. leaders, who have also spent an outsized amount of face time with their Pakistani counterparts. As secretary of state, Hillary Clinton has made four trips to Pakistan, compared with two to India and three to Japan. Mullen made more than twenty visits to Pakistan.

To be sure, Mullen was not the first U.S. official to publicly point the finger at Islamabad, nor will he be the last. Washington’s tactic—criticism coupled with continued assistance—has not been effectual. Threats and censure go unheeded in Pakistan because Islamabad’s leaders do not fear the United States. This is because the United States has so often demonstrated a fear of Pakistan, believing that although Pakistan’s policies have been unhelpful, they could get much worse. Washington seems to have concluded that if it actually disengaged and as a result Islamabad halted all its cooperation in Afghanistan, then U.S. counterinsurgency efforts there would be doomed. Even more problematic, the thinking goes, without external support, the already shaky Pakistani state would falter. A total collapse could precipitate a radical Islamist takeover, worsening Pakistani relations with the U.S.-backed Karzai regime in Afghanistan and escalating tensions, perhaps even precipitating a nuclear war, between Pakistan and India.

WEIGHING OF DEEDS

The U.S.-Pakistani relationship has produced some successes. Pakistan has generally allowed NATO to transport supplies through its territory to Afghanistan. It has helped capture some senior Al-Qaeda officials, including Khalid Sheik Muhammad, the 9/11 mastermind. It did permit the United States to launch drone strikes from bases in Baluchistan.

Yet these accomplishments pale in comparison to the ways in which Pakistan has proved uncooperative. The country is the world’s worst nuclear proliferator, having sold technology to Iran, Libya, and North Korea through the A. Q. Khan network. Although Islamabad has attacked those terrorist groups, such as Al-Qaeda and the Pakistani Taliban, that target its institutions, it actively supports others, such as the Haqqani network, the Afghan Taliban, and Hezb-i-Islami, that attack coalition troops and Afghan officials or conspire against India. Pakistan also hampers U.S. efforts to deal with those groups. Meanwhile, Pakistan refuses to give the United States permission to conduct commando raids in Pakistan, swearing that it will defend Pakistani sovereignty at all costs.

A case in point was the raid that killed Osama bin Laden. Rather than embrace the move, Pakistani officials reacted with fury. Of course, the operation was embarrassing for the Pakistani military, since it showed the armed forces to be either complicit in harboring bin Laden or so incompetent that they could not find him under their own noses. But Pakistan could easily have saved face by publicly depicting the operation as a cooperative venture.

The fact that Pakistan distanced itself from the raid speaks to another major problem in the relationship: despite the billions of dollars the United States has given Pakistan, public opinion there remains adamantly anti-American. In a 2010 Pew survey of twenty-one countries, Pakistanis had among the lowest favorability ratings of the United States: 17 percent. The next year, another Pew survey found that 63 percent of the population disapproved of the raid that killed bin Laden.

Washington’s current strategy toward Islamabad, in short, is not working. Any gains the United States has bought with its aid and engagement have come at an extremely high price and have been more than offset by Pakistan’s nuclear proliferation and its support for the groups that attack Americans, Afghans, Indians, and others.

PLAYING THE DOUBLE GAME

It is tempting to believe that Pakistan’s lack of cooperation results from its weakness as a state. One version of this argument is that much of Pakistan’s civilian and military leadership might actually want to be more aligned with the United States but is prevented from being so by powerful hard-line Islamist factions. Another explanation of the weakness of the Pakistani state is that the extremists in the government and the military who support militants offer that support despite their superiors’ objections.

Still, there is a much more straightforward explanation for Pakistan’s behavior. Its policies are a fully rational response to the conception of the country’s national interest held by its leaders, especially those in the military. Pakistan’s fundamental goal is to defend itself against its rival, India. Islamabad deliberately uses nuclear proliferation and deterrence, terrorism, and its prickly relationship with the United States to achieve this objective.

Pakistan’s nuclear strategy is to project a credible threat of first use against India. The country has a growing nuclear arsenal, a stockpile of short-range missiles to carry warheads, and plans for rapid weapons dispersion should India invade. So far, the strategy has worked; although Pakistan has supported numerous attacks on Indian soil, India has not retaliated.

Transnational terrorism, Pakistanis believe, has also served to constrain and humiliate India. As early as the 1960s, Pakistani strategists concluded that terrorism could help offset India’s superior conventional military strength. Pakistani militant activity in Kashmir has led India to send hundreds of thousands of troops into the province. Better that India send its troops to battle terrorists on its own territory, the Pakistani thinking goes, than march them across the border. Further, the 2008 Mumbai attack, which penetrated the heart of India, was a particularly embarrassing episode for India’s security forces.

Pakistan’s double game with the United States has been effective, too. After 9/11, Pakistan’s leaders could hardly resist pressure from Washington to cooperate. But they were also loath to lose influence with the insurgents in Afghanistan, which they believed gave Pakistan strategic depth against India. So Islamabad decided to have things both ways: cooperating with Washington enough to make itself useful but obstructing the coalition’s plans enough to make it nearly impossible to end the Afghan insurgency. This has been an impressive accomplishment.

CREDIBLE THREATS

As Mullen’s comments attest, U.S. officials do recognize the flaws in their country’s current approach to Pakistan. Yet instead of making radical changes to that policy, Washington continues to muddle through, working with Pakistan where possible, attempting to convince its leaders that they should focus on internal, rather than external, threats, and hoping for the best.

The one significant policy change since 2008 has been the retargeting of aid to civilians. Under the Obama administration, total assistance has increased by 48 percent, and a much higher percentage of it is economic rather than security-related: 45 percent in 2010 as opposed to 24 percent in 2008. The Enhanced Partnership with Pakistan Act of 2009, which committed $7.5 billion to Pakistan over five years, conditioned disbursements on Pakistan’s behavior, including cooperation on counterterrorism and the holding of democratic elections.

Despite Pakistan’s ongoing problematic behavior, however, aid has continued to flow. The United States has shown that the sticks that come with its carrots are hollow. The only way the United States can actually get what it wants out of Pakistan is to make credible threats to retaliate if Pakistan does not comply with U.S. demands and offer rewards only in return for cooperative actions taken. U.S. officials should tell their Pakistani counterparts in no uncertain terms that they must start playing ball or face malign neglect at best and, if necessary, active isolation. Malign neglect would mean ending all U.S. assistance, military and civilian; severing intelligence cooperation; continuing and possibly escalating U.S. drone strikes; initiating cross-border special operations raids; and strengthening U.S. ties with India. Active isolation would include, in addition, declaring Pakistan a state sponsor of terrorism, imposing sanctions, and pressuring China and Saudi Arabia to cut off their support.

Of course, the new U.S. “redlines” would be believable only if it is clear to Pakistan that the United States would be better off acting on them than backing down. (And the more believable they are, the less likely the United States will have to carry them out.) So what would make our threats credible?

- The United States must make clear that if it ended its assistance to Pakistan, Pakistan would not have escalation dominance; Pakistan would be even worse off if it retaliated. The United States could continue its drone strikes, perhaps using the stealth versions of them that it is currently developing. It could suppress Pakistani air defenses. The United States could conduct some special operations raids, which would be of short duration and against specific targets. Pakistan might attempt to launch strikes against NATO and Afghan forces in Afghanistan, but its military would risk embarrassment. Moreover, if Pakistan started tolerating or abetting Al-Qaeda on its own soil, the country would be even more at risk.

- The United States must show that it can neutralize one of Pakistan’s trump cards: its role in the war in Afghanistan. Washington must therefore develop a strategy for Afghanistan that works without Pakistan’s help. That means a plan that does not require transporting personnel or materiel through Pakistan. Without Pakistan the coalition could still support a substantial force in Afghanistan, just not one as big as the current one of 131,000 troops. And given the Obama administration’s current plans to withdraw 24,000 U.S. troops by this summer—with many more to follow—such a drawdown is already in the cards.

- Washington must shed its fear that its withdrawal of aid or open antagonism could lead to the Pakistani state’s collapse, a radical Islamist takeover, or nuclear war. Pakistanis, not Americans, have always determined their political future. Even substantial U.S. investments in the civilian state and the economy have not led to their improvement or to gains in stability. As for the possibility of an Islamist takeover, the country’s current power centers have a strong interest in maintaining control and so will do whatever they can to keep it—whatever Washington’s policy is. The possibility that nuclear weapons could wind up in the hands of terrorists is a serious risk, of course, but not one that the United States could easily mitigate whatever its policy in the region. As for Pakistan’s nuclear posture, it will not alter that posture because it is so effective in deterring India, and there is not much that the United States, or anyone else, can do to change that—good relations or not.

From a U.S. perspective, then, there is no reason to think that malign neglect or active isolation would make Pakistan’s behavior or problems any worse.

HEADS I WIN, TAILS YOU LOSE

Even as the United States threatens disengagement, it should emphasize that it would still prefer a productive relationship. But it should also make clear that the choice is Pakistan’s: if the country ends its support for terrorism; works in earnest with the United States to degrade Al-Qaeda, the Taliban, and the Haqqani network; and stops its subversion in Afghanistan, the United States will offer generous rewards. It could provide larger assistance programs, both civilian and military; open U.S. markets to Pakistani exports; and support political arrangements in Kabul that would reduce Islamabad’s fear of India’s influence. In other words, it is only after Pakistan complies with its demands that the United States should offer many of the policy proposals now on the table. And even then, these rewards should not necessarily be targeted toward changing Pakistan’s regional calculus; they should be offered purely as payment for Pakistan’s cooperation on the United States’ most important policies in the region.

A combination of credible threats and future promises offers the best hope of convincing Islamabad that it would be better off cooperating with the United States. In essence, Pakistan would be offered a choice between the situation of Iran and that of Indonesia, two large Islamic states that have chosen very different paths. It could be either a pariah state surrounded by hostile neighbors and with dim economic prospects or a country with access to international markets, support from the United States and Europe, and some possibility of détente with its neighbors. The Indonesian path would lead to increased economic growth, an empowered middle class, strengthened civil-society groups, and a stronger economic and social foundation for a more robust democracy at some point in the future. Since it would not directly threaten the military’s position, the Indonesian model should appeal to both pillars of the Pakistani state. And even if Islamabad’s cooperation is not forthcoming, the United States is better off treating Pakistan as a hostile power than continuing to spend and get nothing in return.

Implicit in the remarks Mullen made to the Senate was the argument that Washington must get tough with Pakistan. He was right. A whole variety of gentle forms of persuasion have been tried and failed. The only option left is a drastic one. The irony is that this approach won’t benefit just the United States: the whole region, including Pakistan, would be better off.