What are unmanned weapons and where did America’s quest for autonomy begin? The answer takes us back to the birthplace of the country and David Bushnell’s famed kegs of floating gunpowder then to the Civil War when, first Confederate and then Union generals experimented with land and naval mines and tethered torpedoes, and finally, how the invention of aircraft, the radio, and two World Wars ushered in a new age of autonomy.

WATCH THE EPISODE

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: The Hand Behind Unmanned America's quest for Autonomous War.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: A little over a decade ago, in the midst of the global war on terror, Julia and I noticed there was something we couldn't quite explain about the United States fascination with the unmanned systems that dominated the battlefield at that time.

Predators and the Reapers. We were conducting interviews with the folks on the ground, calling in airstrikes, and we noticed the mythology around unmanned. On one hand, there was this distrust of systems remotely controlled from thousands of miles away, and on the other hand, a deep belief that unmanned and autonomy was the future of war.

It all culminated in a discussion that we were having at a Marine base. The Marines in the room had just recounted concerns about trust and risk with unmanned aircraft, especially when they were in a situation with the potential for a fratricide called danger close. But then one Marine raised their hand.

Guys, we may not like it, but unmanned is inevitable. And that was the beginning of the puzzle for us. Here were the war fighters, and they were assuming an inevitability about the technology. But Julia and I knew that these technologies were a product of human decisions. Somewhere along the way, we'd bought into a myth that technology progresses independent of human choices.

But that's not true. So we set out to tell the story of the human hand behind Unmanned. And in the process, we discovered the people, beliefs, and identities that shaped America's autonomous arsenal.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: Welcome to the Hand Behind Unmanned, a podcast about how America fights war without human beings, told from the perspective of the human beings making those choices.

I'm Jackie Schneider.

>> Julia MacDonald: And I'm Julia McDonald. In this podcast, we take you inside weapons budget lines and behind classified program doors to understand not only what unmanned technology the US Military bought, but why. For those of you who came for the technology, we hope you'll stay for the people.

Because this really is a story about remarkable humans, historical junctures, and our beliefs about the future of war and what that means for unmanned weapons, we buy. Along the way, in our unmanned journey, we'll learn valuable lessons about how technology shapes the winners and losers in war. How humans and technology interact at a time when the march of technological progress seems inevitable, how public funds get invested when it comes to warfare, and above all, the human hands at the heart of unmanned technology.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: I'm Jackie Schneider. I'm the Hargrove Hoover Fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, and I'm the director of Hoover's War Gaming and Crisis Simulation Initiative. Before coming to Stanford, I was a professor at the Naval War College, and I've served 20 years in the air Force as both an active duty and reserve intelligence officer.

I have a PhD in Political Science and my research looks at the intersection of technology, national security and political psychology.

>> Julia MacDonald: I'm Julia McDonald. I'm a research professor at the University of Denver's Corbell School of International Studies, and I'm also Director of Research and Engagement at the Asian New Zealand foundation in Wellington, New Zealand.

Along the way, I've served in a variety of roles in the New Zealand government focused on defence and national security. I have a PhD in Political Science and my research looks at questions around use of force decisions and military strategy and effectiveness. What is unmanned anyway?

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: We take an expansive view of what we mean by unmanned and really it's about being unhuman.

How technology can distance the human from the act of violence in war, sometimes that means that a system is uncrewed but remotely operated. Sometimes it means that the system has some autonomy or freedom to choose its target. But maybe it's launched by something else that's manned, like an aircraft or a destroyer.

Some unmanned systems are smart and autonomous, but others, and to be honest, probably historically most are kind of dumb and automated. There is a huge spectrum of capability, missions, and ways in which unmanned technologies have shaped historical and now modern battlefields.

>> Julia MacDonald: Sounds a bit complicated, but let's turn to our colleague, friend and defense expert from the center of a new American security, Paul Scharre, to make this a little simpler for us.

Paul has literally written the book on autonomy titled The Army of None.

>> Paul Scharre: The terminology here is really slippery because you put like 10 experts in a room to define autonomy. You come out with 15 different definitions and I think what's hard is people will talk about a spectrum of autonomy, but there's actually like three different dimensions to this spectrum.

So one is this idea of the relationship between the person and the machine. And so you get terms like semi autonomous where there's a human in the loop and the machine's taking some action, it stops, and then the human has to push a button or take some action for it to continue.

You get supervised autonomous systems where the human is on the loop and then the machine is performing some task and the human could intervene. And if they're not happy with what it's doing. So an example might be like a self driving car today, if it's in some kind of autopilot mode and you're sitting there letting it drive, but the human could intervene.

And then you have fully autonomous systems where the human is out of the loop and there's not a way to intervene or at least not in a timely fashion. And so that might be like you hop in one of these Waymo taxis and you're just in the backseat and there's no steering wheel.

Whatever happens, happens, right? So that's one dimension of autonomy. But there's another dimension that also people will use terms like automatic and automated and autonomous to refer to. That's about the complexity of the machine. And so you can have really simple systems that we tend to call automatic where there's this really direct feedback between input and action.

So examples might be a tripwire or a landmine or like an old mechanical thermostat or toaster, right? So you make some setting and it's a really simple, it's mechanical oftentimes actually like the input and output, then you assist those that might be more complicated that we would tend to call automated.

Where there's some set of parameters that a human sets for how it functions. An example there might be like a programmable thermostat or based on the times of days, you know, this is how it, what actions it's going to perform. Then people use terms like automated to refer to something that is more sophisticated that might be goal oriented.

And so there's a goal that this system is trying to achieve. So an example might be with a self driving car, okay? The goal is the destination and it's taking input from the environment. It's making decisions about how to drive to get there. And you can imagine like that's different than some very simple pre programmed car that just drives straight forward, you know, for 100 meters and then turns right and then drives a certain amount of distance.

That's going to work on a closed track. But these differences are really slippery in practice. So sometimes people will say like, well, we're going to build this thing, it's autonomous. And then they build it and then they can now see the inner workings of what it does. And people say, well, is it autonomous?

Maybe it's just automated. And so I think those are different concepts in some ways, right? And it's useful to use the term. But it's also maybe not like a really hard and fast definition. And I think that's important when we think about, you know, whether it's inside the DoD or internationally, things like regulating kind of some of these systems, like some of these terms are easier to define and pin systems down.

And then the third dimension that's really important is just what is it doing? What is the task that you're having the machine do? And that's critically important. So you look at like a top of the line automobile today and they have features like intelligent cruise control and automatic braking and self parking, you know, different tasks that start to get automated.

Or you could say the machine is autonomous to do that task, right? And that's true in the military space too, right? So you have fire and forget missiles that can maneuver their way to the target, but the human still chooses the target. Think about a targeting cycle in military operations.

Which task are we automating or which task we're making? Autonomous is really critically important. So let's talk about like a lock on after launch homing missile, right? That's launched from an aircraft. So you launch this missile, a pilot is launching it at something at an enemy target, but it's not wire guided, it's not being remotely controlled once it's launched.

And so on one level you might say the missile is fully autonomous once it's launched. And that's a fair way to characterize it. You're not going to recall that you don't have any control over it. But is it finding its own targets? Is it deciding in some grander sense which targets go after, no, it's being launched at something in particular.

And so when you think about sort of the scope of its autonomy, it's relatively narrow. And some of this gets a little bit technical. So it depends on things like, okay, when does the seeker turn on? Is it turning on before launch and then the pilot is able to lock onto a target or is it turning on after launch?

If it's turning on after launch, how big is the search radius for this weapon system? How big is the seeker acquisition basket, right? Use a kind of a technical term people use, basically the field of view of the seeker that it might lock onto. A lot of these munitions are really aimed to go after like a specific target where you would say, well, the human is still choosing the target.

The human knows what it's going after, but not all of them. There are examples like the Israeli Harpy drone that searches over a really wide area. It's an anti Radar drone. And you don't have to know the specific target that you're going after. It searches over a big area.

In the 80s, the US Navy had a missile called the Tomahawk anti ship cruise missile, the tasm, that would do this. You sort of launch it over the horizon in the general direction of Soviet ships. And it was queued by some kind of naval aviation asset, an ISR asset, that would say, okay, we know there are ships here.

But the time delay was such that by the time the missile got there, the ships were going to move during this really big search pattern. And that's a place where then you're kind of giving that machine more freedom, more autonomy. And then, like what task machines doing, what is the human doing?

It starts to get a little bit blurrier.

>> Julia MacDonald: As Paul illustrates, autonomy and unmanned are not necessarily new to the American battlefield. And in fact, the quest for technology to replace humans on the battlefield is almost as old as war itself.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: For centuries, people have tried to find ways to fight wars without humans.

There are reports of unmanned balloons and mines in ancient China. In the 1500s, Leonardo da Vinci sketched out an unmanned vehicle that could take off and land without a pilot. The United States flirtation with autonomy started at the birth of our great nation. During the Revolutionary War, Yale graduate David Bushnell was intrigued by the potential to use asymmetric technology.

In this case, we're talking about floating kegs of gunpowder to harass the very fancy and very much more capable British navy. His first combat experiment was to send tethered mines, firepower kegs with a crude contact fuse that were attached by rope to the American very small vessel towards a British frigate that was harassing American ports near New London, Connecticut.

A nearby British schooner noticed the line and reeled it onto the vessel to inspect the unknown object. At that point, the mine exploded, sinking the schooner and killing three sailors. Now that was not Bushnell's intended target. The actual target was the British frigate Cerberus. But it left an impression on the British navy.

The captain of the British frigate wrote back to England. The ingenuity of these people is singular in their secret modes of mischief. Bushnell and the Americans would continue their mischief in the waters off of New Jersey. When Bushnell sent 40 floating mines down the Delaware river, trying to sink the British ships anchored in Philadelphia harbor.

The kegs were more or less duds. None of them hit any British vessels, but they caused widespread panic. And for a full day, the impressive British navy expended their guns on anything floating in the harbor. Was it a resounding success for the Americans? No, but it did make the great British Navy look a bit ridiculous.

And it became a rallying cry for those mischievous Americans, which they then captured in song.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: The US would once again try its hand with minds both in the water and on land during the Civil War. Confederate generals in particular, one General James Raines, laid mines in both ground and naval campaigns in order to combat a far better equipped Union military.

Coincidentally or maybe not, General Rains had previously experimented with landmines during the Seminole wars, hiding shells under the bodies of dead soldiers. But disastrous results. In one particularly gruesome episode, an American landmine set up by Opossum drew American soldiers out of the fort, only to be attacked by a waiting group of Seminole Indians.

The Union military wasn't pleased with Rain's use of landmines, but to be fair, nor was all of the Confederate military leadership. But the north begrudgingly began to adopt land mines as they moved into Southern Territory. Union General Tecumseh Sherman wrote in June 1864, I now decide that the use of the torpedo is justifiable in war in the advance of an army.

But after the adversary has gained the country by fair warlike means, then the case changes entirely. The use of torpedoes and blowing up our cars and the road after they are in our possession is simply malicious. I think this is an important time to pause because at the end of the 19th century, technology began to catch up to the imagination of these warfighters.

Whereas before, if you wanted unmanned, you had to accept that removing the human via technology would come with very little control and therefore a very high chance of both failure and fratricide. But Moving into the 20th century, technological advances in radio gyroscopes and other electronic guidance mechanisms opened up a world of possibilities for unmanned technology.

In particular, these turn of the 20th century Technological innovations ushered in a golden age for the torpedo or self propelled guided naval mines. Let's turn to Dr. Kate Epstein, Associate professor of history at Rutgers Camden, whose book Torpedo tells the story of the rise of the technology in the late 19th century into World War I.

>> Kate Epstein: There's kind of this well known race, you know, you get a more powerful gun, you get more powerful armor, you then get an even more powerful gun, even more powerful armor, and so on. But actually the gun and the torpedo were in a competition as well. And the stakes of it were really like would the capital ship, the battleship.

And the battle cruiser kind of remain viable ways of kind of projecting combat power on the world's oceans. The great thing about a torpedo is you only really need one hit from it to potentially sink a ship, whereas chances are you're going to need multiple hits from a gun.

So the basic competition is really basically about range. How far can you expect to make a certain percentage of hits at? How you define what's an acceptable percentage of hits or an acceptable probability of hitting is a subjective judgment. It's not like there's some Platonic form of like, here's the percentage of hits you need to make.

But basically every time the torpedo's range got longer, the more important it became for ships to be able to hit with their guns.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: In many ways, the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century looks a lot like today. It was a time of technological and political uncertainty where these militaries had to make a decision about what unmanned they were going to buy.

But it had big effects on the manned force structure.

>> Kate Epstein: That was, to me, one of the kind of shocks of writing the book. I always thought that, like, tactics were fairly straightforward, and it was strategy that it was the hard part. Well, not if, every single technology that your extremely technologically intensive combat arm uses is changing at the same time.

So it's ship armor, ship gunnery, optics, telecommunication. So radio is coming on ships. So, figuring out, you kind of pity these officers, figuring out what the next battle was actually going to look like was intellectually actually like a very difficult challenge.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: These technological innovations made the torpedo, and to some extent the mine, the dominant unmanned weapon of World War I.

But it wasn't the US that was leaning into these technologies. It was the Germans, whose submarine U boats launched an unrestricted campaign against Allied shipping and combat vessels throughout the Atlantic. It was a German torpedo that sunk the American ship Lusitania, killing over a thousand and drawing the US officially into World War I.

In total, German and Austro Hungarian U boats equipped with torpedoes sank almost 5,000 merchant ships during World War I, killing approximately 15,000 Allied sailors. It was a gruesome war, a war in which unmanned technology, torpedoes, to some extent naval mines, and very crude landmines dug into the Western Front created cruel and enormous losses of life.

And it wasn't how the US Wanted to fight the next war. Which could help to explain why, despite experimentation between World War I and World War II, the US navy largely shuttered its mine and torpedo industries. Faced with declining defense budgets, the Navy moved the munitions to the bottom of their priority lists behind the new aircraft, submarines and carriers the service was clamoring for.

That left the Navy in a game of catch up when World War II began. As Robert Gannon, author of Hellions of the the Development of American Torpedoes In World War II, dryly noted. The Navy was left with a tiny dribble of beautifully crafted torpedoes, barely less erratic than their World War I forefathers, produced by an organization corpulent, sluggish, and not so much consciously resistant to change as physically and emotionally unable to.

But maybe it's not really the Navy that dropped the ball. Maybe what makes torpedoes and mines less interesting is that there's something new on the scene. Air power may have made a timid debut in World War I, but it was a full blown teenager by World War II, anxious to show its independence and impact on the modern battlefield, it had mixed success.

It was the Japanese, not the Americans, that launched perhaps the most ambitious use of unmanned aerial systems during the war. Between 1944 and 1945, the Japanese launched 9,300 explosive laden balloons, of which 361 eventually arrived in North America. But the United States was not far behind the Japanese.

The US Navy employed a squadron of unmanned aircraft in the Pacific. The Army Air Force also sent a handful of unmanned bombers against targets in Germany. And both services used drones so heavily for targeting practice that that a British invention, the O Q2 radio plane, became the world's first mass produced drone.

In all this experimentation, there were some serious duds, no doubt because even the new developments in radar and electronic transmissions couldn't overcome the extraordinary difficulty of controlling these systems, especially in war. One of the best examples of these failed experiments was Operation Aphrodite, in which unmanned B17s were stripped down of any armor and equipped with twice the firepower of a normal B17.

Unfortunately, the unmanned B17 couldn't take off safely on its own, and so the plane required a pilot and co pilot to take off from inside the cockpit. They would then transfer control to the mothership and parachute from what was at that point a B17 drone. It was a complicated and dangerous concept.

In the end, Operation Aphrodite and the Navy version Anvil included only 14 missions. Four crew members were killed, including the older brother of future president John F Kennedy. And none of the drones ever successfully bombed their targets. The program was terminated, but General Spaatz ordered that a few of the platforms be left displayed, ostensibly ready to launch, in order to leave in the minds of the Germans the threat of robot attacks.

>> Julia MacDonald: So we're going to stop here and fast forward now through a few decades and multiple wars to the 21st century, when predator and Reaper drones became household names thanks to the war on terror. And now, two decades later, over the skies of Ukraine, soldiers are sending thousands of small, cheap drones to spy, attack and resupply the lines of what has become a Duggan war of very human attrition.

So what happens in those decades and through those wars? That will be the subject of the rest of this podcast. But first, let's take a second to talk about how we can understand those investments over the next half a century. I think what our quick montage through unmanned history shows is that the US Arsenal of drones and remotely piloted aircraft didn't come about from some sort of predetermined linear pathway getting more and more advanced as time went on.

Instead, it's more like a maze than a pathway, a jumble of dead ends, rabbit holes, and hidden passages.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: That's complicated. So sometimes we look for the easiest explanation for why some weapon systems are bought and others never make it to the battlefield.

>> Julia MacDonald: The first of these is the technology explanation.

Simply put, unmanned arsenals are driven by technological development. As technology gets better, more and more capable unmanned appear on the battlefield. And certainly, that explains a lot about unmanned technology. We needed the radio, the radars, computers to make unmanned a reality on the battlefield. But that doesn't explain why we have remote controlled aircraft instead of conventional long range missiles.

It doesn't explain why so little innovation has occurred within the US Inventory of mines. And it certainly, doesn't explain why the Air Force, the service of pilots, led the adoption of unmanned over the last few decades. The second, simpler explanation is what we call a capacity hypothesis. Simply put, more dollars in equals more unmanned capabilities out.

States need investments in an industrial base, in research and development, and in procuring or buying unmanned things. More investment equals more unmanned things.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: Let's turn to Mike Horowitz. He's the Director of Perry World House and the Richard Perry professor at the University of Pennsylvania. He's also the Senior Fellow for Technology and Innovation at the Council on Foreign Relations.

For two years, he was the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Force Development and Emerging capabilities, which means he literally wrote the book on what types of autonomous technologies the US should be buying. But maybe most importantly, he's a military innovation and military technology proliferation expert, his first book, the Diffusion of Military Power, explained why some states adopt technology and others fail to follow their lead.

>> Michael Horowitz: If we're talking about the proliferation of ungrud technology, we're really talking about two things. One is the spread of the different technologies themselves, and the second is the ability of militaries to actually adopt them. And those are different things. We've really seen increasingly widespread diffusion of uncrewed technologies, driven in large part because the technological availability is just there and the price point is right, and they've increasingly been proven as effective in a lot of different real world conflicts.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: So one simple explanation is that the more capacity a state has to buy and build these technologies, the more likely unmanned systems are to diffuse and proliferate across militaries. Certainly capacity matters. The capacity comes after choices made by humans about which weapons and technologies we think will help us win a future war, these human choices are driven by beliefs, beliefs about what wars we will have to fight and how technology will shape those wars.

As Ben Johnson, director of the Futures Lab, a senior fellow for the Defense and Security Department at the center for Strategic and International Studies, a professor at Marine Corps University, explains, I think there's.

>> Benjamin Jensen: A tendency sometimes to assume that there's a degree of technological push or even technological determinism.

But all of a sudden, gadgets fall from the sky and antiquated warriors fumble with them and then start to change how they fight. But most of my journey has found the exact opposite. Usually, it's the imagination of the warrior that allows you to kind of see new opportunities on the horizon.

And then there's this just fascinating, often under theorized, complex interactions with the defense bureaucracy and civilian scientists and industry that kind of lead to often strange pathways for different technologies that no one might have chosen initially, but that end up kind of growing out of that complex negotiation.

>> Julia MacDonald: Untangling this knot to understand how these beliefs translate into lines within a congressional budget tells us something far beyond A rote inventory of unmanned systems. It tells us how ideas transit circuitous paths, how they diverge and intersect based on chance meetings and belief chaperones. And how some beliefs find themselves in dead ends while others become ingrained within identities and ultimately shape the budgets and technologies of military arsenals.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: This is a podcast about human beliefs about the role of identity, organizational culture and the American way of war. In this episode, we told you a bit about the humans that drove early American autonomous experimentation. But after World War II, technology and a new US military created new human agency about which technologies we would invest in.

People had to lead influence campaigns for weapons lobbying in Congress, the halls of the Pentagon, and within the intellectual foundation of American national security. These are what we scholars might call policy entrepreneurs. But they are the true influencers influencing the biggest choices about what the US buys, really?

This is their story.

>> Julia MacDonald: As we've seen in this episode, even as technology makes it more and more possible to fight wars without human beings, humans have had a constant, complex and fascinating role to play. Humans don't just design, the technologies, also decide whether they'll be built, bought and used.

They say yes to bad technologies and say no to great ones. Sometimes emotions and pre existing beliefs get in the way. And sometimes those same beliefs allow them to make truly revolutionary choices about American military effectiveness. The way people and organizations think about technology, that is the beliefs that they hold about them are crucial to understanding their use and proliferation.

People and institutions cultivate, adopt and then champion these beliefs to build support for certain weapons within the political system. When shocks occur like a war or a political crisis, windows of opportunity open for these actors to push forward their ideas, navigating budget cycles and attempting to make their preferred policies stick.

So you may have been with us at the beginning for a story about technology, but this is a story just as much about the invisible human hand as it is about unmanned technology. Making that human hand more visible in the saga of unmanned technology reveals something about how states choose the ways in which they fight wars.

It helps us to better understand the relationship between human nature, organizations, states and the conduct of war. In the next few episodes, we'll see the role of beliefs and identity play out across US history. We'll start with the beginning of the nuclear age. We'll move to Vietnam and the end of the Cold War.

Introduce you to a post Cold War American military, the Gulf War and 20 years of a war on terror. In our last episode, we'll look to the future and explore how wars in Ukraine, Israel and the Red Sea may influence the trajectory of the US Unmanned arsenal. Will it be an arsenal of exquisite drones and long range precision?

Or will the coffers be filled with quadcopters and small attritable systems? Start the journey with us in episode two. I'm Julia.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: And I'm Jackie.

>> Julia MacDonald: This is the Hand Behind Unmanned podcast. If you liked it, buy the book. It's by Oxford University Press and available on Amazon.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: Thanks for listening.

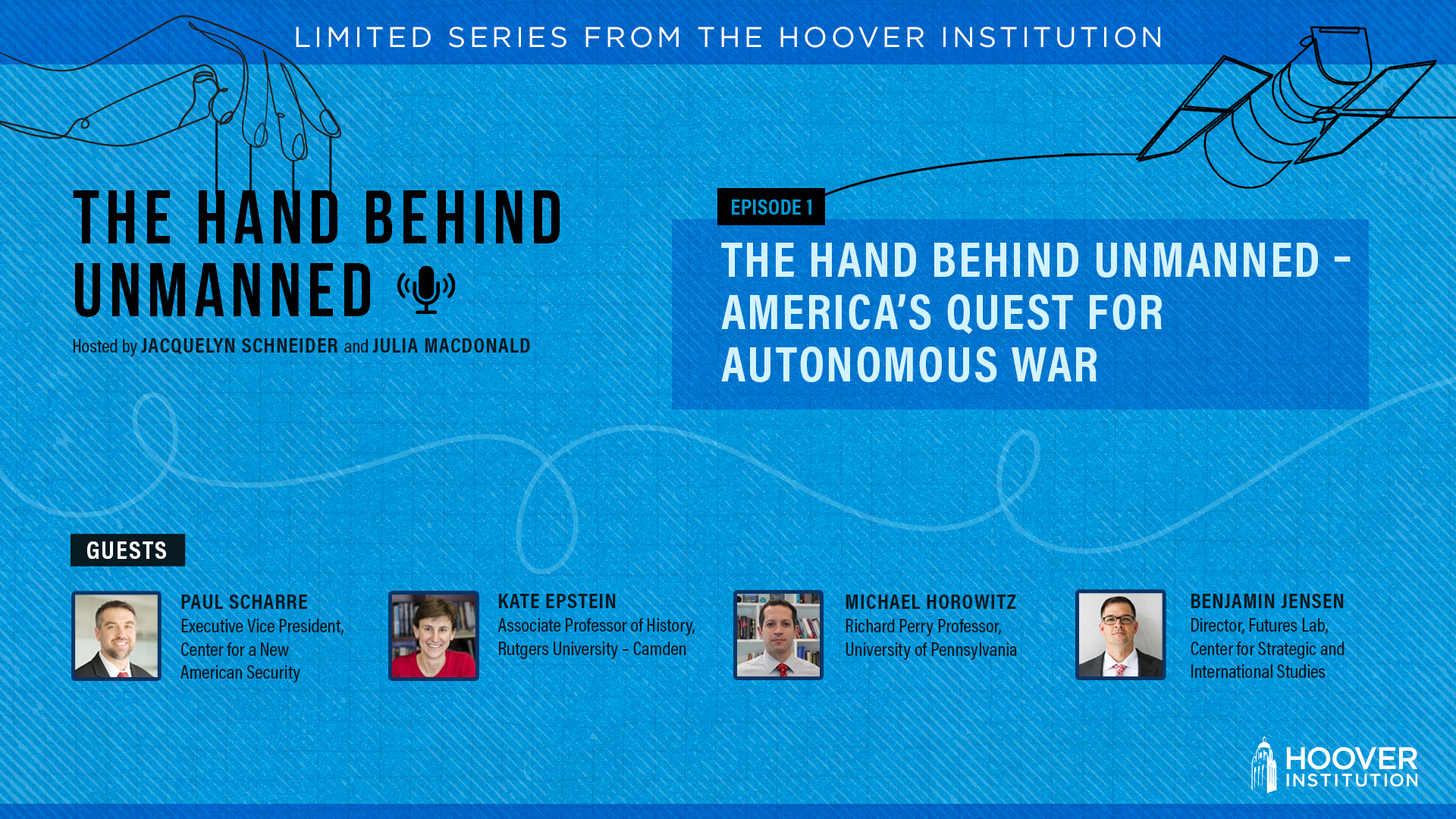

ABOUT THE GUESTS

Paul Scharre is the executive vice president at the Center for a New American Security and award-winning author of Four Battlegrounds: Power in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. His first book, Army of None: Autonomous Weapons and the Future of War, won the 2019 Colby Award, was named one of Bill Gates’ top five books of 2018, and was recognized by The Economist as one of the top five books to understand modern warfare. Scharre previously worked in the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) and served as a special operations reconnaissance team leader in the Army’s 3rd Ranger Battalion. He holds a PhD in war studies from King’s College London and an MA in political economy and public policy and a BS in physics from Washington University in St. Louis.

Kate Epstein is an associate professor of history at Rutgers University– Camden. Her research focuses on the intersection of defense contracting, intellectual property, and government secrecy in Great Britain and the United States, as well as the “hegemonic transition” from the Pax Britannica to the Pax Americana. She is the author of two books: Analog Superpowers: How Twentieth-Century Technology Theft Built the National-Security State and Torpedo: Inventing the Military-Industrial Complex in the United States and Great Britain.

Michael Horowitz is the director of Perry World House and Richard Perry Professor at the University of Pennsylvania. He is also senior fellow for Technology and Innovation at the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). From 2022 to 2024, he served as deputy assistant secretary of defense for force development and emerging capabilities. He is the author of The Diffusion of Military Power: Causes and Consequences for International Politics, and the co-author of Why Leaders Fight. Professor Horowitz received his PhD in government from Harvard University and his BA in political science from Emory University.

Benjamin Jensen is the director of the Futures Lab and a senior fellow for the Defense and Security Department at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). At CSIS, Jensen leads research initiatives on applying data science and AI and machine learning to study the changing character of war and statecraft. He is also the Frank E. Petersen Chair for Emerging Technology and a professor of strategic studies at the Marine Corps University School of Advanced Warfighting (MCU). Jensen has authored five books including Information at War: Military Innovation, Battle Networks, and the Future of Artificial Intelligence; Military Strategy in the 21st Century: People, Connectivity, and Competition; Cyber Strategy: The Evolving Character of Power and Coercion; and Forging the Sword: Doctrinal Change in the US Army. He also served as senior research director for the US Cyberspace Solarium Commission. He is a reserve officer in the US Army, with command experience from platoon to battalion. Jensen graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and earned his MA and PhD from the American University School of International Service.

RELATED SOURCES

- Army of None, by Paul Scharre (W.W. Norton, 2019)

- The Diffusion of Military Power: Causes and Consequences for International Politics, by Michael C. Horowitz (Princeton University Press, 2010)

- Torpedo:Inventing the Military-Industrial Complex in the United States and Great Britain: by Kate Epstein (Harvard University Press, 2014)

- Forging the Sword: Doctrinal Change in the US Army, by Benjamin Jensen (Stanford University Press, 2016)

- The Hand Behind Unmanned: Origins of the US Autonomous Military Arsenal, by Jacquelyn Schneider and Julia Macdonald (Oxford University Press, 2025)