- US

- Contemporary

- Military

- World

- Security & Defense

- US Defense

- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- The Presidency

- History

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

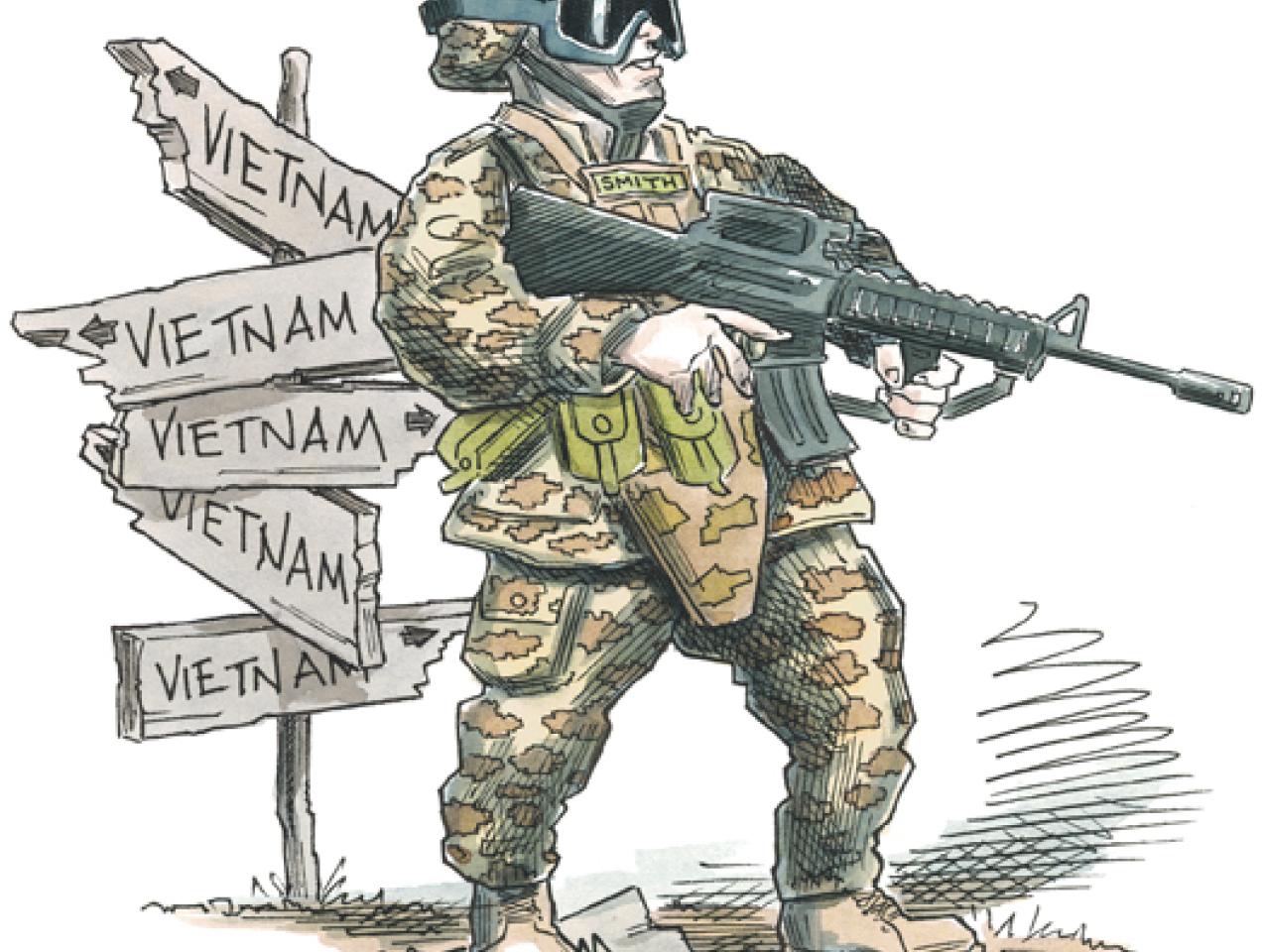

The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and the political debates concerning the nature and scope of U.S. involvement in those countries, have resurrected the “lessons” of Vietnam once again. Far from having kicked the “Vietnam syndrome,” as President George H. W. Bush put it in the exuberant aftermath of Operation Desert Storm, it now seems possible that the memory of the Vietnam War will be forever conflated in the public imagination with the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq, producing something like a Vietnam syndrome on steroids.

Some of this is understandable. In Afghanistan and Iraq, the United States is engaged in conflicts of the sort that, after the painful experience of the Vietnam War, many believed our nation would never again fight. As the debate over U.S. policy and strategy in Iraq and Afghanistan intensified last year, voices on all sides invoked Vietnam to support their arguments. Some suggested that at the level of grand strategy, the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq were related campaigns in the broader war on terror, just as Vietnam was one chapter in a wider Cold War; others, making the case in ideological terms, likened today’s global fight against adherents of Salafi jihadism to yesterday’s struggle against world communism. Afghanistan and Iraq also evoke the American experience in Vietnam because they present complex problems with a multitude of political, military, economic, and cultural dimensions.

Additional Vietnam analogies range far and wide. Iran’s proxy wars against Israel, the Lebanese government, and the United States, waged through Tehran’s support for Hamas, Hezbollah, Afghan militias, and Shiite groups in Iraq, add a dimension to the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq reminiscent of Chinese and Russian support for their proxy in Vietnam. Porous Afghan and Iraqi borders combined with sanctuaries in neighboring countries provide insurgent and terrorist organizations room to maneuver and havens to organize, plan, and train for operations. Like Vietnamese communist insurgents, Taliban and Iraqi armed groups intimidate the populace, wage effective propaganda campaigns, and use terrorism to undermine local and U.S. efforts to establish security, build governmental institutions, and complete reconstruction projects.

But it is in the operational realm that Vietnam analogies have truly come to life. Like arguments over the lessons of Vietnam, debates over the effect of the “surge” in Iraq and the strategy that preceded it have focused on deficiencies in America’s conceptual approach to the Iraq war. Just as analysts such as Colonel Harry Summers argued that a neglect of the operational art led to a disjuncture between tactical means and strategic ends in Vietnam—the result, in his telling, of focusing the Army too much on counterinsurgency rather than on its traditional war-fighting strengths— today some military officers and analysts argue that the Army has become mesmerized by the techniques and procedures of counterinsurgency, few of which they credit for recent successes in Iraq.

And just as the opposing side of the Vietnam debate argued that an American force wedded to conventional orthodoxy was ill-suited for and failed to adapt to the challenges of combating an insurgency in the complex geographic and cultural environment of Southeast Asia, scholars such as Conrad Crane have made the point that the U.S. military was ill-prepared for counterinsurgency operations in Afghanistan and Iraq—mainly because it regarded Vietnam as an aberration and then as a mistake to be avoided.

Many historians criticize the late Robert McNamara and other architects of America’s intervention in Vietnam for having slighted the human and psychological dimensions of war and refusing to pay due respect to the complex Vietnamese communist strategy of Dau Tranh—a strategy that employed a mosaic of shifting political and military actions—and a critique of American military policy in Iraq levels a similar charge. It faults those who initially devised military policy in Iraq for having revived the Vietnam-era conceit that the United States had discovered the secret of using violence with minimal uncertainty and a high degree of efficiency: the mere demonstration of American military prowess, policy makers argued at the outset of both conflicts, would be sufficient to alter the behavior of the enemy. This flawed assumption had similar effects in each case: the United States dramatically underestimated the complexity of war and the level of effort and time required to achieve its wartime objectives.

“GRADUATED PRESSURE” AND A RATIONAL WAR

How and why did America go to war in these places, and what best explains the course of these wars? Evidence that became available in the mid-1990s, including documents and tapes of meetings and phone conversations, shed new light on the Johnson administration’s Vietnam War decision making thirty years earlier. That evidence indicated that the answers to these two questions were connected: the unique way in which the United States went to war in Vietnam had a profound influence on the conduct of the war and its outcome. In Iraq, too, the way the United States went to war influenced everything that followed. A fixation on American technological superiority and an associated neglect of the human, psychological, and political dimensions of war doomed one effort and very nearly the other.

Our record of learning from the past, particularly the American experience in Vietnam, is not strong. As Yuen Foong Khong argued in her book Analogies at War: Korea, Munich, Dien Bien Phu, and the Vietnam Decisions of 1965, it was the misapplication of history that so muddled analysis and decision making during the escalation of American involvement in Vietnam. Similarly, America’s memory of the divisive military intervention in Vietnam is easily manipulated because it is foggy and imprecise, more symbolic than historical. There are dangers in the reflexive application of historical memory; it clouds understanding and justifies poorly devised policies. Thus historian Earl Tilford argued that the only true lesson of Vietnam was that the “United States must never again become involved in a civil war in support of a nationalist cause against communist insurgents supplied by allies with contiguous borders in a former French colony located in a tropical climate halfway around the world.”

It is true that the conflicts in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan exhibit many more differences than similarities. But although the uniqueness of Vietnam limits what we might apply directly from that experience, an examination of how and why Vietnam became an American war and what went wrong there can also help us think more clearly about the wars of today and tomorrow. Indeed, as long as we resist the temptation to expect simple answers from history, strategic and operational insights from the war in Vietnam can be relevant and helpful to our efforts in Afghanistan and Iraq.

A fairly obvious insight, or so one might think, is the conclusion that no easy solution presents itself in Afghanistan and Iraq, just as none did in Vietnam forty years ago. Success in Vietnam meant defeating enemy insurgent and conventional forces, countering enemy political initiatives, and helping the South Vietnamese government and military develop the effectiveness and legitimacy necessary to secure the population, address people’s basic needs, and turn people against the communists. The United States, however, was drawn toward a simple solution that proved inadequate to the complexity of the conflict.

The way the United States went to war in Vietnam was unique in American history. No one decision led to war. President Johnson did not want to go to war, yet every decision he made seems in retrospect to have led inexorably in that direction. Not that Johnson relished such decisions: he turned to his secretary of defense, Robert McNamara, to develop a strategy for Vietnam compatible with his domestic priorities and one that would permit the president to avoid a concrete decision between war and disengagement.

Approved in March 1964, “graduated pressure” was the result. The strategy would use raids and tit-for-tat bombing to persuade Ho Chi Minh and the leaders of North Vietnam to desist from supporting the communist insurgents in the South. Graduated pressure would allow the United States to control the escalation of the military effort and improve the situation cheaply, efficiently, and without attracting undesired attention from Congress and the American people.

The principal hallmarks of graduated pressure—maximum results with minimal investment, a conviction that the enemy would respond rationally to American action, an obsession with technology as a defining element of warfare—responded to multiple needs unrelated to the actual situation. They were, however, consistent with the education and professional orientations of the architects of the American war in Vietnam. For these men— McNamara, William Bundy, John McNaughton, and the “whiz kids” who surrounded them—human relations were best viewed through the lenses of rational-choice economics and systems analysis. The persistence of nasty, divisive, “irrational” political impulses did not figure much into their worldview. Further, technological innovations had, at least in their telling, endowed these policy makers with an ability to use force in a precise and calibrated way, one that would not set loose the dogs of war.

Nowhere did these conceits manifest themselves more clearly than in the application of systems analysis to a guerrilla war half a world away from Washington. U.S. planners should assume that the enemy “is in much the same position as we” and will “adapt his behavior,” one of the deans of systems analysis, Thomas Schelling, wrote in 1964. The precise, rational application of force would culminate in the United States and its adversary reaching “simultaneously a judgment about what is the most reasonable choice for us to make and what is a reasonable choice for him to be making.” Drawing on English legal tradition, McNaughton and Bundy went so far as to assert in Vietnam planning papers that U.S. policy would establish a “common law” justification for bombing North Vietnam; Hanoi would enter negotiations soon after the United States established a “common law pattern of attacks.” But Pentagon planners and White House advisers failed to account for a commitment to revolutionary war that permitted bloodshed on a scale unimaginable to American white-collar professionals.

The inflated expectations for graduated pressure accompanied a belief that technological prowess obviated the need to think too much about the nature of the enemy or about the human and psychological complexities of war. In fact, McNamara and his principal assistants were oblivious to those human and psychological dimensions. Their faith in U.S. technological superiority, combined with their assumption that the enemy would conduct himself like any rational actor, blinded them to the character of their North Vietnamese and Vietnamese communist foes. Nor, even in later years, did this faith in technology abate. The litany has been well chronicled—the overwhelming reliance on airpower, the overhyped use of sensors and other technologies to slow movement down the Ho Chi Minh trail, McNamara’s proposal to erect an electronic barrier along the seventeenth parallel, the quantification of even the most fundamentally human aspects of warfare. Even facing defeat, American planners forged ahead.

A FATAL MISREADING OF THE ENEMY

The failure of graduated pressure was foretold in 1964 by two eerily prophetic Pentagon war games. In those simulations, Southeast Asia experts played the role of the North Vietnamese government. In response to limited bombing designed to signal American resolve, those experts decided to infiltrate large numbers of North Vietnamese army soldiers into the Central Highlands of South Vietnam. This, in turn, impelled the commitment of American troops to the South. The war games concluded that the combination of enemy sanctuaries in North Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos; the enemy’s ability to sustain itself on meager provisions; its strategy of emphasizing political and military actions to avoid strength and attack weakness; and limitations on the application of American military power would mire the United States in a protracted conflict with little hope for success. The game ended after five years of fighting with five hundred thousand troops committed in South Vietnam; Bundy, however, found the conclusion “too harsh.”

Thus those war games had no effect on American policy or strategy. Graduated pressure was based on a contrary assumption—that applying limited military force would signal American resolve and thereby persuade the enemy to alter his behavior. The strategy, however, failed to consider military actions in political, cultural, geographic, economic, or historical context. Vietnamese communist leaders were committed to winning even if victory came at an extraordinarily high price; they had demonstrated that commitment as recently as the first Indochina war (1946–54) against the French. The North Vietnamese were culturally predisposed toward patience and a long view. Ho Chi Minh and other Hanoi leaders viewed their fight against Americans in the context of previous struggles against the French, Chinese, and Japanese. Moreover, the North Vietnamese economy was primarily agrarian, which meant that bombing its infrastructure had limited usefulness. That covert operations and selective bombing would force the enemy to “desist” was a fantasy—but it was a necessary fantasy if the president was to escape making what he feared would be unpopular decisions.

In November 1964, Assistant Secretary of Defense John McNaughton wrote a twenty-page analysis for an interdepartmental committee led by William Bundy and devoted to the question of what to do next in Vietnam. Although McNaughton’s recommendation for a strictly controlled and carefully limited bombing campaign against North Vietnam— “progressive squeeze and talk”—would soon be enshrined in official policy, its author had misgivings. McNaughton began to doubt that the acutely limited military action he favored could persuade the North to stop supporting the Viet Cong. In a memo, he wrote that his favored course stood “some chance of coming out very badly.” Nevertheless, McNaughton and other officials in the Defense and State Departments believed that if the North Vietnamese did not respond to the gradual application of military pressure, the United States could simply stop using force. Graduated pressure was designed to allow “maximum control at all stages and to permit interruption at some appropriate point or points for negotiations, while seeking to maintain throughout a credible threat of further military pressures should such be required.”

Even McNamara had his doubts. But, in an effort to give his president the advice he wanted to hear, McNamara convinced himself and others that the strategy of graduated pressure was feasible.

Nineteenth-century Prussian philosopher Carl von Clausewitz argued that “the first, the supreme, the most far-reaching act of judgment that the statesman and commander have to make is to establish the kind of war on which they are embarking, neither mistaking it for, nor trying to turn it into, something that is alien to its nature. This is the first of all strategic questions and the most comprehensive.” The problem in South Vietnam was fundamentally political, but the strategy of graduated pressure did not address the fundamental causes of violence. Planned military actions were based on readily available weapon systems and other capabilities, rather than on the objectives that the application of military force was meant to accomplish. Because the president and his advisers considered only the next step up the “ladder” of graduated pressure, the strategy hindered long-range thinking about purposes and policies and barely acknowledged U.S. interaction with the enemy.

To the extent that criticism of strategic thinking did enter into the discussion, it hardly slowed the momentum behind graduated pressure. In a November 1964 planning memo, a senior civilian Pentagon planner defined the primary objective in Vietnam as the preservation of American credibility and concluded that it was unnecessary to win the war to achieve that objective. America simply had to “get bloodied” and appear to the world to have been a “good doctor” who did all he could for a terminally ill patient. This approach ignored the uncertainty of war and the unpredictable results of an activity that involves killing and destroying. To the North Vietnamese, attacks on their population and the bombing of their countryside were not simply means of communication or a game of chess. The results of the bombing campaign, as with any act of war, created problems—and emotions—to which coldly rational calculations provided no adequate response.

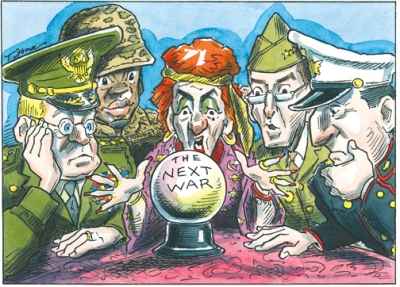

Although terms like “signals” and “messages” were banished from the lexicon of U.S. military affairs after Vietnam, the search for magic bullets—and a related neglect of the human and intangible dimensions of warfare—persists even now. The strategic concept for future war that emerged in the 1990s bears a striking resemblance to an earlier, repudiated approach to the use of force. This concept resurrects a set of theories tested and found wanting four decades ago.

A TRANSFORMATION BASED ON HUBRIS

The “shock and awe” campaign that opened the war in Iraq illuminated not only Baghdad’s skyline but also a vision of warfare that has tantalized American defense professionals for generations. The operation would be quick, precise, and efficient in its means, predictable in its outcome. Explaining that America’s purpose was to make war on a regime rather than a nation, a senior American official summarized the desired objective: “You would be able to bring new leadership but we were going to keep the body in place.”

But the body—the Iraqi army and governmental institutions, which were expected to switch sides eagerly and intact—melted away (before being disbanded entirely) or collapsed, presenting the American-led coalition instead with groups of unconventional fighters operating within a failed state. The insurgency that would grow and coalesce over time did not comply with a strategy of decapitation. And the distinction between regime and nation was not as clear as war planners had assumed.

Far from reconstituting itself quickly and peaceably once freed from tyrannical rule, the Iraqi state appeared on the brink of fragmentation. Some had expected wholesale enthusiasm for the liberation, yet an element of the population engaged in armed opposition. And defying the prediction that U.S. forces could draw down quickly and depart, as the champions of “speed over mass” predicted, the war took a distinctly nonlinear course as an insurgency, militias, and criminal organizations filled the void left by Saddam Hussein’s oppressive regime.

On the eve of the invasion, a senior Pentagon official predicted: “I can’t tell you if the use of force in Iraq today will last five days, five weeks, or five months, but it won’t last any longer than that.” More than six years later, it is clear that the initial planning for the war misunderstood the nature of the conflict, underestimated the enemy, and underappreciated the difficulty of the mission.

Along with an assumption that the enemy would respond to American military action in a fairly predictable and reasonable manner, the proponents of concepts such as “shock and awe” and “rapid decisive operations” believed, like the whiz kids before them, that technological prowess would free them from the enduring logic of warfare. In the years just before the attacks of September 11, 2001, enthusiasm about a “defense transformation” epitomized American military thought. Advocates of this transformation believed that information, communications, surveillance, and precision strike capabilities had generated a revolution in military affairs that would deliver quick, cheap, efficient, and decisive victories in future wars. The language of defense transformation was hubristic—U.S. forces would enjoy “full spectrum dominance” over potential adversaries so long as they maintained a technological advantage. Once more, faith in American technological superiority had elevated a military capability to the level of strategy, and once more, the human element had gotten lost in the enthusiasm for what seemed to present a relatively painless solution to a complex problem.

The conviction that technology offered a panacea not only impeded U.S. efforts in Afghanistan and Iraq to begin with but also slowed the ability to adapt once the true nature of those wars became apparent. In late September 2004, as the insurgency in Iraq was coalescing and U.S. forces were preparing for the battle of Fallujah, the secretary of defense continued to make the case that “speed and precision and agility can substitute for mass,” reiterating that the war plan was designed “to take advantage of the speed, precision, and agility that we have.” Such views go a long way toward explaining the mismatch between ends and means in Afghanistan and Iraq, where for years the United States chased ambitious aims with inadequate resources (especially numbers of soldiers and units committed).

Decisions against deploying coalition forces in numbers sufficient to secure populations left many commanders with no other option than to adopt a raiding approach to counterinsurgency operations—an approach that tended to reinforce the perception of coalition forces as aggressors and conflated tactical successes with strategic effectiveness. Inadequate troop strength and the approach it impelled created opportunities for the enemy. The Iraqi insurgency gained this respite in part because of the belief that America’s technological superiority would permit a small U.S. force to achieve effects disproportionate to its size even when fighting among the population.

Although technology has contributed significantly to operational successes in Iraq—such as efforts to hunt down terrorist leaders or the ability to target roadside bomb cells—those tactical efforts would have achieved only limited results had they not been combined with improved security for the Iraqi population, which helped break the cycle of sectarian violence, generate precise human intelligence, and deny the enemy the ability to hide in plain sight. After local and tribal leaders felt secure enough to participate in their own security, they proved to be the most effective protection against enemy attack and, along with Iraqi security forces, the best guarantors of security writ large.

“EFFICIENCY” MISSES THE POINT

Paradoxically, concepts associated with the so-called revolution in military affairs were based partially on the desire to avoid another Vietnam. In the 1990s, the Weinberger-Powell doctrine of overwhelming force was eclipsed by the certainty that U.S. technological superiority would deliver in future wars what had proven so elusive in Vietnam: rapid, decisive victory. If an adversary had the temerity to threaten U.S. national security interests, a transformed military would mount “rapid decisive operations” that would “shock and awe” any and all foes. The most enthusiastic proponents of these concepts argued that U.S. technological advances would “lock out” potential adversaries from the “market” of future conflict. “Networkcentric warfare” counted on surveillance and information technologies to deliver “information dominance” over all potential adversaries.

Applied to Afghanistan and Iraq, these ideas invited Americans to indulge in the conceit that decisive victory would henceforth be achieved by small numbers of U.S. forces backed with superior technology. Three years after the invasion of Afghanistan and one year after the invasion of Iraq, senior defense officials continued to advocate a “10-30-30” idea for national defense under which small, light forces would deploy to a distant theater in 10 days, defeat the enemy within 30 days, and then ready themselves for another mission in another 30 days. Similar to the concept of graduated pressure, concepts like rapid decisive operations and the associated 10-30-30 plan were mostly grounded in visions of wars that defense officials would like to fight rather than the kinds of wars that current and potential enemies were likely to force upon them.

As with graduated pressure’s premise that limited attacks would alter enemy behavior, the belief that surveillance and information technology would permit rapid decisive operations became a surrogate for strategic coherence, disconnecting war planning from war’s political goals. The late Admiral Arthur Cebrowski and John Garstka wrote in 1998: “When 50 percent of something important to the enemy is destroyed at the outset, so is his strategy. That stops wars—which is what network-centric warfare is all about.” But this is backward: the elevation of tactical capabilities to the level of strategy divorces the tactical employment of forces from their strategic objectives.

Because counterinsurgency, for one, is fundamentally a political problem, the framework that connects tactics to strategy ought to be a political scheme that directs and integrates an entire array of initiatives, actions, and programs in the areas of security, political transition, reconstruction, economic development, governmental development, diplomacy, and the rule of law. As David Galula observed in his 1964 book Counterinsurgency Warfare: “So intricate is the interplay between the political and the military actions that they cannot be tidily separated; on the contrary, every military move has to be weighed with regard to its political effects and vice versa.” In his recent book, Why Vietnam Matters, Rufus Phillips argues that the political and psychological component of American strategy was missing in Vietnam because of a failure to “recognize the ultimate political nature of the war during the critical years 1963–1968.” The same might be said of the initial strategies for the Afghanistan and Iraq wars.

Like McNamara’s whiz kids, advocates of the revolution in military affairs applied business analogies to war and borrowed heavily from economics and systems analysis. Both graduated pressure and rapid decisive operations promised efficiency in war; planners could determine precisely the amount of force necessary to achieve desired effects. Graduated pressure would apply just enough force to affect the adversary’s “calculation of interests.” Under rapid decisive operations, U.S. forces, based on a “comprehensive system-of-systems understanding of the enemy and the environment,” would attack nodes in the enemy system with a carefully calculated amount of force to generate “cumulative and cascading effects.”

But the U.S. experience in Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq demonstrated that it was impossible to calibrate precisely the amount of force necessary to prosecute a war. The human and psychological dimensions of war, along with the friction and uncertainty when opposing forces meet, invariably frustrate even the most elaborate and well-considered attempts to predict the effects of discrete military actions. Emphasis in planning and directing operations, therefore, ought to be on effectiveness rather than efficiency. The requirement to adapt quickly to unforeseen conditions means that commanders will need additional forces and resources that can be committed with little notice. For efficiency in all forms of warfare, including counterinsurgency, means barely winning. And in war, barely winning can be an ugly proposition.