- Economics

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Budget & Spending

The federal government’s largest two programs, Social Security and Medicare, are at the center of a vibrant national debate over our fiscal future. Each program faces a significant financial shortfall, the solution to which remains elusive.

The following are five myths that have been particularly damaging to our national discussion of Social Security and Medicare.

Illustration by Barbara Kelley

This elusiveness exists in part because of inherent substantive difficulties: many Americans will have to give up something to bridge the significant gaps between program revenues and promised benefits. It’s not easy to forge bipartisan agreement over how to allocate these sacrifices. Yet these decisions have been made unnecessarily difficult by rampant confusion about each program’s finances.

MYTH #1: We "only" have a healthcare financing problem, not a population-aging or senior-entitlement problem. Medicare’s financing shortfall is therefore much bigger and more urgent than Social Security’s.

Unlike many myths that arise from popular ignorance, this damaging myth gained currency through being pushed by several influential policy advocates.

Make no mistake: the growth of healthcare costs is indeed a huge problem. But mainstream budget analysts have long understood that the graying of the Baby Boom generation would by itself create enormous financial challenges. When the Boomers left the ranks of taxpaying workers and entered the ranks of Social Security and Medicare beneficiaries, federal expenditures would soar. These financial strains would be great enough to require a reassessment both of the annual benefits promised to these birth cohorts, and of the number of years they should be allowed to spend in subsidized retirement.

But as George W. Bush’s second term drew toward a close, many of Washington’s influential policy wonks began to sing a different tune. Suddenly population aging wasn’t such a big deal. Even Social Security itself didn’t face such a large problem. The entire fiscal shortfall was due, it was now said, to healthcare alone.

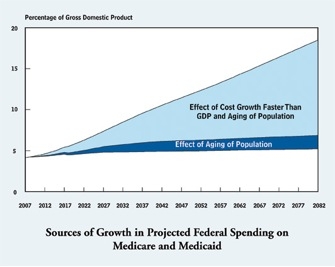

Proponents of this new line of argument were legion. Brookings Institution scholar Henry Aaron asserted flatly that "there is no general entitlement problem. Rather, the nation faces a daunting healthcare financing problem. . ." AARP head Bill Novelli echoed the new line, saying that "we don’t have an age problem; we have a healthcare cost problem." When Peter Orszag (Novelli’s cited source for his claim) became director of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), that agency soon published a controversial chart purporting to show that healthcare inflation utterly dwarfed population aging as a contributor to the long-term fiscal imbalance. CBO corrected this in later publications, but a lasting misimpression had already been made.

The Long-Term Outlook for Healthcare Spending

(As Shown by CBO, November 2007)

Photo credit: Congressional Budget Office

This line was enormously attractive to politicians then assuming office at both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue. President Barack Obama himself soon declared, "Make no mistake, healthcare reform is entitlement reform." If Social Security specifically and population aging generally were minor problems, politicians were off the hook for tough calls concerning benefit levels and eligibility ages. Expert opinion was now offering a rationale for doing what politicians liked best—expanding promised benefits—instead of warning of the necessity of scaling untenable promises back. One direct consequence of this widely repeated rhetoric was the passage of yet another federal health entitlement last year.

All of this inflicted incalculable damage upon prospects for righting federal finances, as deficit hawks knew all along that it would. While the urgency of Social Security reform was downplayed, its finances deteriorated even more rapidly than previously projected. The troublesome long-term budget outlook that some had attributed entirely to unreformed healthcare now remains just as bleak after healthcare reform. Indeed, the health legislation erected still more barriers to fiscal consolidation, for example when the Obama administration declared that the new law’s insurance exchanges were to remain untouched in recent budget negotiations.

Even if it hadn’t been so damaging, the myth would still be flatly untrue. While Medicare as a whole poses the larger financial challenge over the long term, Social Security’s shortfall is of comparable magnitude and is by some actuarial measures even larger. The latest Trustees’ reports find that Social Security’s imbalance equals 2.22 percent of its tax base over the next 75 years ($6.5 trillion in present value), whereas Medicare’s is 0.79 percent ($3.0 trillion). And from now through 2025, Social Security will not only remain the more expensive of the two programs, it will actually grow more in the aggregate.

We must revise our entitlement benefit promises to seniors.

In sum, population aging will remain a bigger financial challenge even than health cost inflation for decades to come. The vast majority of long-term cost growth in Social Security and Medicare, for example, is projected to take place by 2035. The CBO now attributes 64 percent of cost growth through 2035 in Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid to population aging, even though two of these programs are health entitlements.

There is of course a kernel of truth in the myth—just enough to permit its wide circulation. If we could muddle through to 2035 without altering our spending commitments, and if excess health-cost inflation persisted as the health sector swallowed larger fractions of the nation’s economy, then indeed we would later reach a point where healthcare costs overwhelmed all other federal budgetary problems. But no such hypothetical excuses the irresponsible implication that we could indefinitely defer revising our entitlement benefit promises to seniors.

This myth has inspired terrible policy mistakes and cost us valuable time in confronting the most pressing financial problems we face. For Social Security does face a huge financial challenge—indeed, quite comparable to Medicare’s—and population aging still remains the most problematic driver of unsustainable federal spending growth.

MYTH #2: Social Security does not and cannot add to the deficit.

In 2011, Social Security tax income will fall short of payment obligations and the program will add $151 billion to the current federal deficit. Despite this, vocal opponents of Social Security reform have commanded the attention of the press and key public figures when asserting that the program does not add to the deficit. In deference to this rhetorical pressure, elected officials ranging from the Senate’s "Gang of Six" to the president have insisted that Social Security reform take place entirely separately from deficit reduction talks.

Some historical background is important to understanding why this is a fiction. From 1984-2009 inclusive, Social Security did indeed mitigate federal deficits by running annual surpluses of taxes over expenditures. But that positive balance turned into a deficit in 2010 when the onset of Baby Boomer retirements coincided with a recession that depressed payroll tax revenues. Social Security is thus now exacerbating the federal budget deficit and will do so even more in the years ahead.

The argument that Social Security "can’t add to the deficit" is founded on the idea that the program is self-financing, so it can’t spend on benefits beyond what it previously generated in revenues. The money and spending authority now in Social Security’s Trust Funds, it is asserted, simply represent the amount by which the program has thus far reduced federal deficits. In 2036, therefore, when the Trust Funds are depleted, the program’s net effect on the debt to date would theoretically be zero. It can never become a net negative, so the story goes, because the program lacks borrowing authority.

Much of this might well hold water were it not for certain unavoidable realities. First, not all of the money in Social Security’s Trust Funds represents past surplus taxes paid by anyone. Some of the debt was simply issued without any incoming taxes behind it. This year, for example, the Social Security payroll tax was cut while—to make up for the lost revenue—the same law issued $105 billion in further Treasury bonds to its Trust Funds.

In 2011, social security will add $151 billion to the current federal deficit.

Moreover, Social Security is only "not adding to the deficit" this year if we credit the program for interest payments and other transfers of general government revenues. But the CBO is absolutely explicit that such payments do not mitigate the program’s effect of adding to the deficit: "because those interest transactions represent payments from one part of the government (the general fund of the Treasury) to another (the Social Security trust funds), they do not affect federal budget deficits or surpluses."

Indeed, the vast majority of all assets in the Trust Funds represent such interest credits. These interest payments would only reflect a positive long-term budget impact if past surplus Social Security taxes had been saved. Most academic analysis has instead concluded the opposite—that past surpluses stimulated additional federal consumption—instead of being used to reduce federal debt service costs.

In sum, Social Security is clearly adding to the deficit this year—it will add far more in the years to come under current law.

MYTH #3: Medicare’s projected insolvency date is the critical barometer of its financial condition.

This year, the Medicare Trustees (of which I am one) projected that the Medicare HI Trust Fund would be insolvent in 2024, five years earlier than projected in the 2010 Trustees’ report. This five-year acceleration was depicted in press accounts as a serious deterioration of Medicare’s finances.

Medicare’s finances are indeed in dire condition and people are right to be concerned about them. Medicare’s insolvency date, however, is at best an incomplete measure of the program’s finances for at least four reasons.

First, it refers to just one portion of Medicare financing—the Hospital Insurance Fund, or Part A. But Medicare also has a Part B and a Part D funded through another Trust Fund. Because these other parts (B and D) of Medicare are provided by law with the revenues required to match expected costs, solvency is not a meaningful concept for them. The one part of Medicare for which the 2024 insolvency date is relevant actually represents less than half of Medicare’s total cost.

Second, because Medicare’s Trust Fund balances are kept small, even minor annual changes in program finances can cause the projected depletion date to change by several years. The latest five-year deterioration didn’t, for example, reflect a qualitative change. To the contrary, in no year prior to the insolvency date did the new report show an annual worsening (relative to the previous report) even as large as -0.25 percent of the program’s tax base.

Third, Trust Fund solvency only signifies the extent of the program’s financing authority; this is very different from the government’s actual ability to finance benefits. In 2010, for example, the Trustees’ Report found that Medicare provisions in the new healthcare law would extend HI solvency from 2017 to 2029. But other provisions in that same law spent the vast majority of those savings on a new health entitlement. Though this effect would undo much of the supposed improvement in the government’s ability to pay, it is not captured in the Trustees’ projections.

Finally—as with Social Security—Medicare’s insolvency date can be manipulated by government accounting. Congress can issue additional debt to Medicare’s Trust Funds at any time, thereby extending its period of projected solvency without improving the government’s ability to finance Medicare by so much as a penny.

MYTH #4: Social Security projections are conservative; a good portion of its projected shortfall might disappear on its own.

This myth has faded of late as Social Security’s finances are now far worse than its Trustees previously projected. But in recent years, it was almost an article of faith on the American left that the Trustees had been exaggerating the Social Security shortfall with overly conservative projections. It can still be heard on occasion, as in Paul Krugman’s recent statement that "there’s a significant chance, according to [the program’s actuaries’] estimates, that [trust fund exhaustion] will never come."

Actually, there isn’t such a significant chance. A statistical analysis prepared by the Social Security actuaries for the Trustees actually shows that in 90 percent of all projection scenarios, the most that program insolvency would be delayed would be only six years. Moreover, what Krugman refers to as a "significant chance" represents much less than a 1-in-50 probability.

The historical basis for this myth was a fundamental confusion about the elements of current forecasts. Some wrongly assumed that the Trustees were projecting a slowdown in national productivity growth. What the Trustees (like other credible forecasters) actually project is a slowing of net national labor force growth as the large Baby Boom generation retires. Aggregate economic growth is equal to the product of productivity growth times growth in the number of workers. Just as New York’s economy grew more slowly than Texas’s over the last decade because Texas’s population grew faster, our national economy will grow more slowly if workforce growth slows. In fact, contrary to the myth, the Trustees actually assume that real wage growth will somewhat increase going forward.

Pay-as-you-go financing treats younger generations worse and worse as society ages.

A number of commentators have even asserted that the Trustees had a history of overly-conservative projections, particularly with respect to economic growth. This was, as I stated in a paper presented at the American Enterprise Institute in 2007, "empirically incorrect," as the Trustees had been "not a bit too conservative in predicting the present." And in the aftermath of the recent recession, Social Security is now experiencing deficits at an earlier date than predicted in any previous Trustees’ report since the 1983 reforms.

The argument that the Trustees were being "too conservative" has turned out to be nearly 180 degrees from reality. But even before the recent recession, there was never a reasonable analytical basis for it.

MYTH #5: Social Security’s projected solvency through 2036 means that beneficiaries have pre-paid their benefits through that date; any benefit changes, therefore, should be deferred until later.

This unfortunate myth leads to great confusion as to what constitutes a "fair" reform of Social Security.

Workers do not pay in advance for their own benefits under current Social Security law. Rather, the vast majority of each generation’s Social Security payroll taxes are used to pay for the benefits of the previous generation of beneficiaries.

This method of financing, known as "pay-as-you-go," has clear implications for the intergenerational fairness (or unfairness) of Social Security. As the ratio of workers to beneficiaries declines, each succeeding generation must pay a higher tax rate to get the same relative benefit "replacement rate." In other words, pay-as-you-go financing treats younger generations worse and worse as society ages.

Some numbers from the Trustees’ report demonstrate the point. If current benefit schedules are left in place, those now entering the system will lose roughly 4 percent of their lifetime wage income to Social Security, even if they in turn receive all benefits now scheduled for them. Postponing financial corrections until the Baby Boomers are all in retirement thus does not result in workers getting "what they paid for," but rather results in the least equitable treatment across generations.

The reason that the Trust Fund is projected to last until 2036 is not because Baby Boomers have pre-funded a quarter-century’s worth of benefit payments. To the contrary, the Trust Funds are never projected to hold enough assets to fund more than about three and a half years’ worth of payments. From now through 2036, well more than four-fifths of the funds to finance benefit payments will be derived from taxes coming in from younger workers.

In sum, the suggestion that Social Security benefits have been "pre-paid" through 2036 is incorrect, and fosters substantial confusion about what constitutes an equitable solution to the program’s financial shortfall.

These five myths are by no means the only myths that confuse our national discussions of Social Security and Medicare. They are, however, particularly damaging myths of which policy makers would do well to disabuse themselves.