- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

Tony, jagshemash! Jagshemash, Elizabeth! President Nursultan Nazarbayev of Kazakhstan, cordially received in London in November by Tony Blair and Her Majesty the Queen, has proved himself to be a really good sport by taking humorously the satirical portrayal of his country in Sacha Baron Cohen’s film Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan. “This film was created by a comedian, so let’s laugh at it,” said the genial president at a joint press conference with Tony Blair, earning praise from the Sun. Good old Nursultan, friend of Britain, Dick Cheney, BP, Chevron, and Shell.

So, in this spirit of all-round bonhomie, let’s have a few more Kazakh jokes. Have you heard the one about Sergei Duvanov, a real-life Kazakh journalist imprisoned on probably trumped-up charges of child rape after publishing articles about Nazarbayev’s alleged Swiss bank accounts? Or the one about the opposition leader Zamanbek Nurkadilov, found shot dead on the floor of his billiards room shortly before the presidential election, which confirmed Nazarbayev in office with a claimed majority of 91 percent? Or the one about Altynbek Sarsenbaiuly, another opposition leader gunned to death in his car earlier this year? Great jokes, don’t you think? They must have been killing themselves with laughter.

As you will not have gathered from anything said by the prime minister, Kazakhstan is a hugely corrupt dictatorship with a dismal human rights record; a supine judiciary; controlled or intimidated media; and elections that do not, to put it very mildly, come up to the standards of Europe’s leading election monitor, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). President Nazarbayev, having been head of the Kazakh Communist Party and the last president of the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic, has been the president of the newly independent country since 1991 and has now been reelected until 2013.

According to some reports, Sultan Nursultan may now be one of the world’s richest men, but he has not kept his wealth to himself; he has spread it most generously around his immediate and extended family, who control much of the media and many state-owned companies. After socialism in one country, there is capitalism in one family.

I hasten to add (lest a Kazakh joke prove to be no laughing matter) that there is, so far as I know, no evidence linking the Nazarbayev family directly to either of the aforementioned mysterious deaths. What we can definitely say, however, drawing on evidence from many independent reports, is that Kazakhstan has a climate of corruption, lawlessness, and lack of democratic accountability in which such things are liable to happen.

Readers will not be so naive as to ask: “Why, then, the red carpet treatment at Number 10 and Buckingham Palace?” But let me just put a few figures on the answer you have already arrived at. Proved reserves of oil, 26 billion barrels; proved reserves of gas, 3 trillion cubic meters (both 2004 estimates, according to the current CIA World Factbook). There are also major reserves of chromium, lead, zinc, copper, coal, iron, gold, and more across this vast, sparsely populated country, whose westernmost end is closer to Hamburg than it is to the country’s easternmost tip, which borders on China.

| Let’s have a few more Kazakh jokes. Have you heard the one about Sergei Duvanov, a Kazakh journalist imprisoned on probably trumped-up charges after publishing articles about President Nazarbayev’s alleged Swiss bank accounts? |

Britain is the second-biggest foreign investor in Kazakhstan, after the United States. And the West is engaged in a new, triangular great game—competing with our traditional rival Russia and, increasingly, China to control those vital resources. Last year, China National Petroleum bought PetroKazakhstan for $4.2 billion, and a pipeline is to be built all the way to China. Meanwhile, Britain and America are trying to persuade the genial Sultan Nursultan to link Kazakhstan’s Caspian oilfields with a westward pipeline across Turkey. Need I say more? (The services Kazakhstan might render as an ally in the war on terror have also been a consideration, particularly in Washington, but are probably a secondary concern in Britain.)

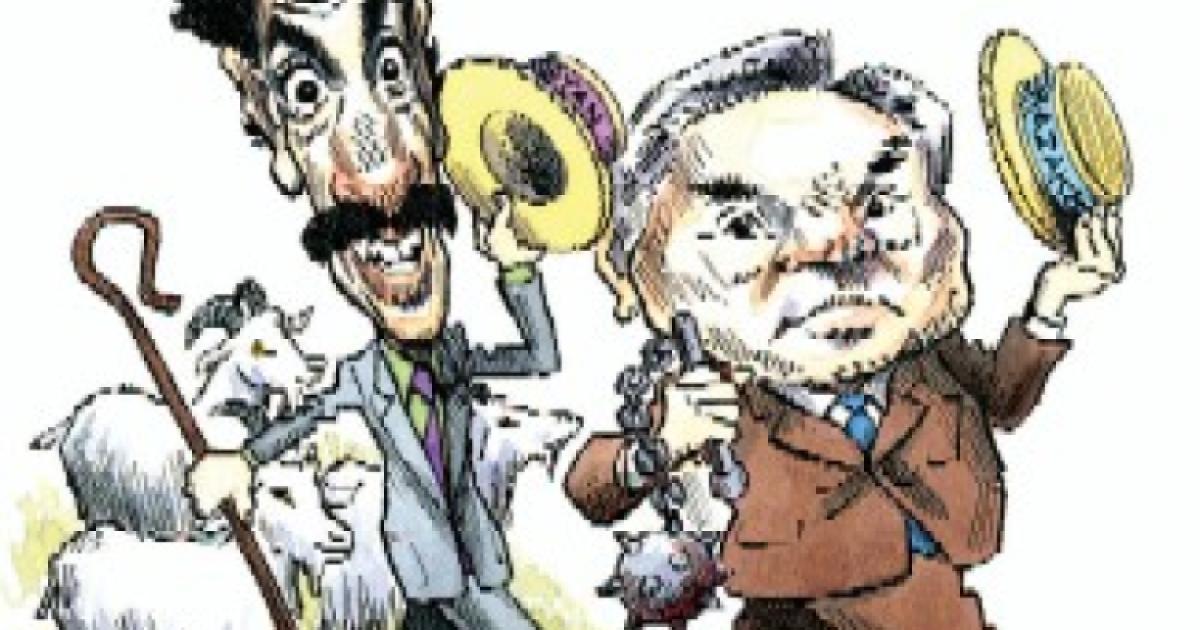

You may think I’m leading up to the conclusion that President Nazarbayev should not have been made so welcome in London. Human rights should come before oil. Certainly, all my instincts pull in that direction. If the human rights situation gets worse, not better, in Kazakhstan, Buckingham Palace may one day remember this visit with as much embarrassment as it does—I hope—the even more splendid welcome given to President Nicolae and Madame Elena Ceausescu of Romania. Remember the wonderful Private Eye cover of the Ceausescus with Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip in full evening dress at a state banquet? In speech bubbles, the duke says: “And does he have any hobbies?” Elena Ceausescu: “He’s a mass murderer.” The queen: “How very interesting.”

One can, however, argue that it’s a gamble worth taking. Significant interests are at stake, both economic and geopolitical. Measured by the standards of contemporary Europe, Kazakhstan is a dictatorship; measured by those of its Central Asian neighbors, such as Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, it’s the best of a bad bunch. Regular visitors tell me there are signs that wealth is beginning to trickle down to start the formation of a more independent-minded middle class. The more involved we are, the more possibilities of influence we have—and you can be sure that China and Russia won’t impose any human rights conditions. Often a policy of constructive engagement can move an authoritarian regime toward reform more effectively than one of isolation. This is what I call “offensive détente.”

| Kazakhstan is a hugely corrupt dictatorship with a dismal human rights record; a supine judiciary; controlled or intimidated media; and elections that do not, to put it very mildly, come up to prevailing standards of fairness. |

But there must be very clear limits, and there must be plain speaking at the end of the red carpet. We should not pretend, to ourselves or anyone else, that Kazakhstan is a democracy or a free country—as we used to pretend with friendly dictators in Latin America during the Cold War. At the same time as engaging with the Nazarbayev regime, we should actively support the growth of independent media, an independent judiciary, civil society, alternative political parties, and so on. Offensive détente always has two tracks.

And sometimes we must just say no. Kazakhstan, which claims to be part of Europe because a fraction of its territory lies west of the Ural River, came to London seeking British support for its bid to chair the OSCE in 2009. It would be ridiculous beyond words if a country whose elections have fallen so far short of OSCE standards, as has its record on human rights and media independence, were to be given this position. Think Mel Gibson as chair of Alcoholics Anonymous, Jack the Ripper in charge of marriage counseling—or Borat being responsible for accuracy in journalism.

| Compared to its Central Asian neighbors, such as Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan is the best of a bad bunch. |

So what response did President Nazarbayev get from Tony Blair and the British government? I asked the Foreign Office and was given this strip of damp flannel as an official response: “Long term, a Kazakh chair would be good for us all. But it is important that any prospective chair exemplifies the standards of the organization in all dimensions. We and our EU partners will continue to discuss the matter with the Kazakh government in the lead-up to the OSCE Brussels ministerial meeting this December.” How many words does it take to say no? From the Foreign Office, during an official visit, the answer is: 55.