- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- Military

- Security & Defense

- US Defense

- Terrorism

- History

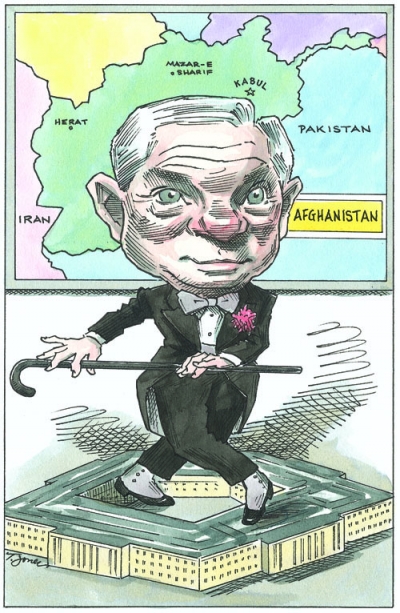

When Napoleon marched his army into Berlin in 1806, he took his generals to the tomb of Frederick the Great and announced, “Hats off, gentlemen; if he were alive we wouldn’t be here.” The same could be said of the Obama administration’s policy on Afghanistan: without Defense Secretary Robert Gates, we would not be here.

Late last year the Obama administration concluded its Afghanistan policy review, formally committing itself to prosecuting the war until Afghan security forces are competent to undertake the work done by U.S. and allied forces. Control of operations will gradually shift to Afghan security forces as military commanders determine them capable of managing the fight. The governments of Afghanistan and other nations providing forces aspire to complete that transition by 2014, although the commander in Afghanistan is reluctant to promise that the target can be met.

This outcome is diametrically opposed to the president’s intention when he first announced the “surge” in Afghanistan more than a year ago. Having been cornered by his own rhetoric about the “good war” in Afghanistan recklessly under-resourced by the previous administration, the president at that time accepted the need to increase forces. But in the very same breath as he gave, he took away: “As commander in chief, I have determined that it is in our vital national interest to send an additional thirty thousand U.S. troops to Afghanistan. After eighteen months, our troops will begin to come home.”

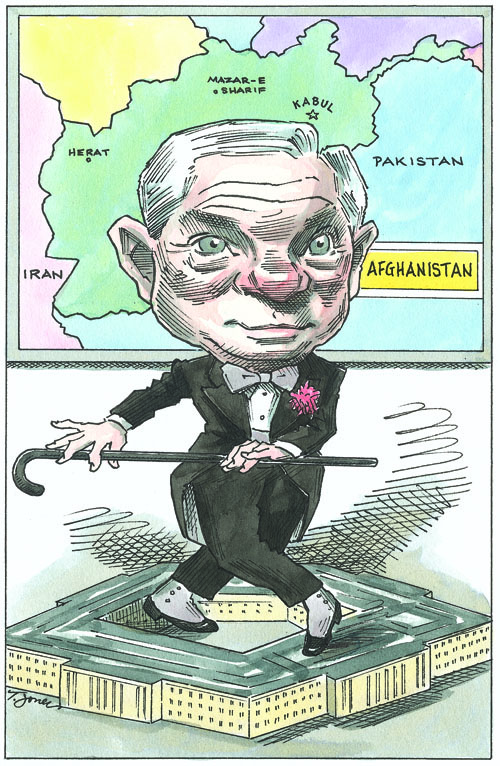

Secretary Gates has a fine Florentine touch for orchestrating outcomes, as we saw in his recent sleight of hand that convinced the public that defense spending is being reduced. But trapping the Obama administration into a sensible alignment of objectives and resources for winning the war in Afghanistan is his coup de grâce. His work repairing the administration’s strategy merits studying.

The first element was preventing the administration from adopting a narrower set of objectives in Afghanistan. Both during the initial administration review announced in early 2009 and the exhaustively drawn out second review, there was significant support by the political faction of the administration for reducing the standard to something that could be met without becoming a distraction from the president’s domestic agenda. Gates made common cause with Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and standing together they were too formidable for Vice President Joe Biden and others to assail. In his West Point speech announcing the conclusions of the second review, the president emphasized that “our overarching goal remains the same: to disrupt, dismantle, and defeat Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan and Pakistan, and to prevent its capacity to threaten America and our allies in the future.”

Having established the goal, Gates put his men in place. Though General David McKiernan had drawn attention to the inadequate resources in Afghanistan, he was judged by both Gates and Admiral Mike Mullen to be insufficiently creative to be entrusted with designing and commanding operations for this complex war. They replaced him with a counterinsurgency expert, General Stanley McChrystal, and also put Gates’s military assistant, General David Rodriguez, in the mix to ensure close ties between the Pentagon and the war effort.

Third, Gates ordered the commander to undertake an independent assessment of how to achieve the administration’s objectives. The McChrystal review accepted the premise of the White House’s policy and made an intellectually unassailable argument for what would be needed in operations and resources, with options directly tied to varying levels of risk. Once the McChrystal standard had been set, it was untouchable by politicians. There was no way to reject the resources the commander said he needed, given the president’s criticism of the previous administration.

Fourth, Gates prevented the strategy debate from becoming a civil-military schism. The White House felt betrayed by the military’s asking for the commitment necessary to achieve the president’s objectives. But when McChrystal injudiciously previewed his views, Gates made a fine show of calling for discipline and insisting that views be conveyed through the chain of command. Thus he protected the military from the White House. When the report leaked (as was inevitable when people on both sides of the argument believed that the administration was about to make a terrible mistake), the Defense Department struck a principled pose about not commenting on internal deliberations, reinforcing the perception of the military as apolitical.

Fifth, in making personnel decisions, Gates made the administration’s strategic decision on Afghanistan. When McChrystal self-destructed, Gates moved the smoothest civil-military operator among the commanders from Iraq to Afghanistan (General David Petraeus) and the finest war-fighting mind of our time (General James Mattis) to CENTCOM. They had written the counterinsurgency manual and were staunch advocates of winning the war. Once they were in place, the White House essentially ceded its preference for withdrawing in June 2011. (Bonus points to Gates for capitalizing on a tactical loss—McChrystal—to achieve a strategic victory.)

Sixth, Gates, Clinton, and our military leadership cajoled NATO into giving the president political cover to extend the deadline. If the United States fails in Afghanistan, NATO fails, and Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen showed enormous skill in keeping allies committed (even if only in name, not troop levels) until 2014 and announcing that commitment at the Lisbon summit. NATO made the extension of the timeline easier for the administration to accept, given its hallowed preference for working through multinational institutions.

Seventh and finally, Gates worked the communications angle brilliantly. A steady drumbeat of news stories about the importance of giving the surge time to work began almost immediately, and then shifted to seeding public expectations that the review would not advocate reducing forces but essentially validate the current course. Just before the president was to make a decision on the review, Gates took a planeload of journalists to Afghanistan to hear for themselves what the people fighting the war believe: it’s a tough fight, it will take time, but it’s winnable and we’re winning. In case anyone failed to draw the correct conclusion, Gates said he was convinced that the strategy was working, publicly delivering his private counsel to the president. Those stories made it very hard for the president to walk away from the war.

Hats off, gentlemen. But for Bob Gates, we would not be here.