- Budget & Spending

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Economics

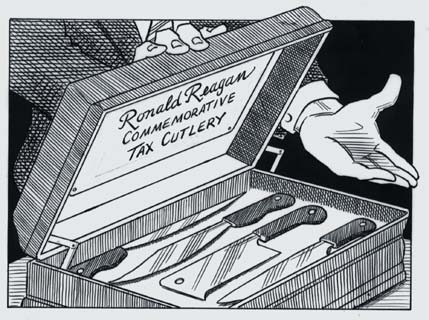

One sure sign that Republican tax cutters are struggling without Ronald Reagan is the fact that they quote him so much. Thus presidential candidate John McCain: “I ask every Republican voter to let my colleagues know that you still believe in the cause Ronald Reagan fought for.” And thus Grover Norquist of Americans for Tax Reform: “[Reagan’s] economic policies of tax cuts, deregulation, and choice for the American taxpayer are largely responsible for the economic good times we are enjoying today.”

Illustration by Taylor Jones for the Hoover Digest Illustration by Taylor Jones for the Hoover Digest |

True enough. But Norquist’s encomium also reveals a problem for the GOP. The whole basis for the tax rebellions of the ’70s and early ’80s was bad times—indeed, astoundingly bad times. In those days, inflation, high taxes, and global uncertainty combined to put the nation in something close to emergency mode. As Reagan said in his first inaugural address, in 1981, “Our objective must be a healthy, vigorous, growing economy.” The dramatic tax cuts that he brought about were a remedy for the period’s unique malaise. While the supply-siders vilified John Maynard Keynes, in this instance they joined the Keynesians in arguing that fiscal stimulus could jump-start a stalled economy. Today, by contrast, the economy hardly needs jump-starting. Growth is back to its old powerhouse levels; there seems to be nothing but blue sky ahead on the inflation front. And, without the old urgency, the GOP tax cutters have trouble marshaling sufficient energy to power through their cuts.

But, while fiscal stimulus no longer seems as urgent, there are good reasons for monumental tax cuts. When Republicans stand up for broad and serious tax cuts, they are also standing up for an old American ideal: faith in the individual. Their efforts, though sometimes faltering, represent a crucial campaign to give the country a tax code commensurate with the current temper of our society. A more appropriate code, in turn, will do much to sustain us on the new path we have chosen.

Consider first, that new path: today we place our faith in individuals and the private sector more than at any time in recent memory—and we are right to do so. We have come to understand that a globalized, technologically driven economy, left to its own devices, will provide for the poor better than welfare ever could. We eye the powerful earnings potential of the stock market and realize that it can provide for better, more reliable retirements than the pay-as-you-go Social Security net. The present administration’s boasts notwithstanding, the very existence of our surprise surplus is proof that it is a dynamic market, not good government, that produces prosperity. The fact that the microchip thrived here and not in Europe (or, as many once predicted, in Japan) is an argument for smaller government. For, even after the tax hikes of the 1990s, the United States has retained a freer (and less taxed) economy than the other great powers.

Anyone who believes that money can be “saved” and returned “later on” through government programs ignores the political history of the New Deal and the Great Society—and the sad legacies of waste, ineptitude, and fraud they’ve left us today.

All in all, America in 1999 is a different country from the nation we knew even, say, twenty-five years ago. There is a new sentiment that government ought to retreat. Blueprint, the magazine of the Progressive Policy Institute (PPI) and a vehicle for New Democratic thinking, recently republished a 1973 Harris poll asking people to describe their views of government. The poll posed the question, “Do you agree or disagree: the best government is the government that governs the least?” In 1973, 56 percent of Americans disagreed with the proposition—that is, they felt the need for big government. But, when the PPI asked the same question of voters in 1998, it got the opposite result. This time, 56 percent of Americans agreed. More tellingly, fewer than two in ten Americans—even fewer than two in ten Democrats—believed that it was the job of government to redistribute wealth.

And yet we still find ourselves with a tax regime built for big government, a massive engine of redistribution more worthy of Mitterrand’s France than the land of the home-office millionaire. Today, the federal tax take represents 20.7 percent of gross domestic product, the highest level it has been in any year except during World War II. A disproportionate share of the new revenue comes from taxes paid by higher earners—taxes on wages and capital gains. In other words, at a time when people are less supportive of redistribution than at any other time in recent memory, the tax code is also more heavily redistributive.

Representative Bill Archer, the Republican chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, has come under attack from the left for advocating an across-the-board tax cut—a tax cut that would include bringing down the top marginal income tax rate for the very highest earners. Democrats generally present this as an affront, and yet it would bring relief for the very people who have created our current prosperity. The reason to give the cash to them is a very simple one: it’s their money. Anyone who believes that money can be “saved” and returned “later on” through government programs ignores the political history of the New Deal and the Great Society—and the sad legacies of waste, ineptitude, and fraud they’ve left us today.

The second argument for broad tax cuts is simply an argument against the intrusion of taxes. Americans are weary of interacting with the tax beast: last year’s furious passage of an IRS reform law—the Senate vote was 97 to 0—is clear evidence of this. But the source of citizens’ fury was not really the IRS, for all its wrongdoings. The demon behind the IRS demon is the code itself. Welfare and other entitlements, as we’ve noted, are out of favor in the ’90s. Lawmakers, Republicans included, have taken all the energy they used to pour into writing entitlements and applied it to the tax code. This exercise in social engineering has produced a maddeningly complex tax system—one that penalizes those who cannot afford to hire their own accountants, which is to say the people the progressive tax code is supposed to succor.

Consider the status of very low earners, a group whom both parties claim to have done so much to protect. In this decade, we have expanded the Earned Income Tax Credit, a cash rebate, to help those people and encourage them to stay in the workforce. But the credit phases out and, in doing so, creates some perverse results. A Congressional Budget Office study shows that, in tax year 1996, two people earning $11,000 each would lose as much as $3,701 in earned income tax cash rebates if they decided to marry—an enormous amount for a household of $22,000. This means precisely what it sounds like: had the pair stayed single, they would have found themselves with $3,701 more to spend.

At the middle income level, other demons emerge. The Alternative Minimum Tax, a vehicle written into law to close loopholes for wealthy taxpayers, now punishes hundreds of thousands of families earning less than $80,000. Within ten years, it will hit nine million.

Bereft of any serious reason to maintain high taxes—we have, after all, no war, no deficit, and a president who has declared the era of big government to be over—why do so many lawmakers still want to spend first and cut later?

And, at the top, the hit is just as hard. In 1997, lawmakers lowered the capital gains tax. In the rarefied halls of economic theory, this move makes sense, for capital is already taxed once at the corporate level. But the reality of the capital gains cut—and another is forthcoming—is that it creates a fresh social division, what we at the Wall Street Journal have called the division between the haves and the almost-haves. On the one hand are the haves, who pay taxes on capital gains at 20 percent or, in some states, 30 percent. On the other hand are the wage slaves, whose entire incomes are subject to heavier income tax levies. Their money is taxed at 40 percent or, in the higher-tax states, 50 percent. This means that the government is depriving these people—professionals, mostly—of the chance to ensure prosperity for their children.

The most important group for the country, after all, is not the wealthy, although we may legitimately wish them well. It is those who hope to become wealthy—a hallowed definition of what it means to be an American. These people look up the progressivity ladder and see only greater punishment awaiting them. The obstacles they face—a top federal tax rate of 40 percent, plus state and local taxes that can put them over the 50 percent line—are higher than the hurdles that confronted their older siblings, who had only Ronald Reagan’s 28 percent bracket to surmount.

A final argument for tax cutting lies in our vision for the future. For, although we may no longer argue the need to “stimulate” the economy, our new individualism tells us that an economy free of the burden of the current code could only do better. And, yes, such growth is likely to have a trickle-down effect in city jobs, in prosperity. Here, the supply-siders’ theories are anything but outdated.

The most immediate penalties for inaction, though, lie in the political sphere. Tax disillusionment is a big part of voter disillusionment. It shows up in declining voter-turnout rates, in the fact that fewer people check the “presidential election campaign” box on their 1040s, and in polls that show declining faith in government. Voters have learned that government often promises serious tax relief but rarely delivers it.

In this sense, the reigning economic philosopher of our era is not Milton Friedman, the free market hero whose thinking so inspired the ’80s warriors. It is another Nobelist, James Buchanan of George Mason University. Leading a school of thought known as public choice theory, Buchanan has argued that the government’s impulse is very much like the impulse of any private-sector business—it wants to compete and grow. This is why, in 1999, bereft of any serious reason to maintain high taxes—we have, after all, no war, no deficit, and a president who has declared the era of big government to be over—many lawmakers, particularly Democrats, still insist on spending first and cutting later.

It is a bitter betrayal and one that tells us that tax cuts—broad cuts, cuts that also benefit “the rich”—can do more than any other policy to restore faith in the social contract. Freedom is necessary to sustain our civil society, as well as the prosperous era we have begun. A great president once said, “Only when the human spirit is allowed to invent and create, only when individuals are given a personal stake in deciding economic policies and benefiting from their success—only then can societies remain economically alive, dynamic.” That was Ronald Reagan, whose broader message can still guide us, after all.