- History

- Military

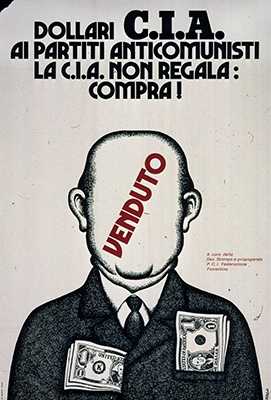

“Mad Mike” Hoare, the most-notorious mercenary leader of the Cold War, died on February 2nd, at age 100. Best known for leading his “Wild Geese” through the turmoil of post-independence Africa—where he served various paymasters, including the CIA—Hoare was a pitiless killer who cultivated a swashbuckling public image. His downfall as a freebooting man of arms came in 1981, when he attempted to overthrow the government of the Seychelles in a murky operation that collapsed into farce at the outset. After a brief stay in a South African prison, Hoare declared that the time for his breed of warrior had passed.

He was utterly wrong. The provision of mercenaries has become big business in our already-crippled century, a venture for corporate-minded entrepreneurs. The day of the small, independent band of warriors may be over, but the hiring of gunmen for auxiliary purposes, from straightforward security work to providing plausible denial for atrocities, has evolved from the drop-off of envelopes of cash to lawyer-vetted contracts for tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars. The mercenary profession has been legitimized by layers of bureaucratic paperwork.

Certainly, twenty-first century mercenaries differ from the brilliant opportunists of the past. Hoare stood in the tradition of the likes of Sir John Hawkwood and his White Company, who became a decisive factor in fourteenth century Italy, prospering grandly amid political chaos, plague, and economic transformation: Today’s mercenary chiefs no longer lead their killers into battle themselves. Instead, they sit behind desks in corporate officers, pausing now and then to chat with heads of state or donation-hungry lawmakers on the phone.

Of course, the mercenary profession has ancient roots, dating to the first, hazy empires, which hired auxiliary forces from their borderlands and beyond. As the Roman Republic mutated into a dictatorial empire, it became ever more unusual to find a recruit from the Italian peninsula in the ranks of the legions that fought its wars. Soldiers of fortune always appeared in turbulent times, and even the United States provided mercenaries since our earliest days, from John Paul Jones’ misbegotten stint in the navy of Catherine the Great to the ill-starred attempts of Confederate officers to serve Maximilian of Mexico just as the latter’s “empire” collapsed.

But while the United States sought to develop local allies, from our western frontier to the Philippines, we did not hire mercenaries to augment our forces. Until now. The advent of our wars in Afghanistan and Iraq opened a gold rush for hired guns. Excused by the logical-but-insidious argument that using armed hirelings for basic security functions freed up our troops for combat roles, the U.S. Government contracted willy-nilly with often-dubious firms that provided services ranging from barring the unworthy from dining facilities to protecting diplomats on the move.

Like many a disastrous decision, it sounded like a good idea to besieged and desperate bureaucrats. And we wound up employing steroid-addled hooligans who murdered local civilians, from dusty villages to central Baghdad. During reporting visits to Iraq in the early years of the occupation we shrunk from calling what it was, the most-frequent complaint I heard from tactical leaders was about the indiscipline and callousness of security guards whose wanton actions often undid a year or more of building local relationships.

We Americans stress—and believe—that we are not in the business of building a traditional empire. But something in our moral consciousness changed, for the worse, in the Middle East over the past two decades. The turning point may have come conclusively during the tenure of now-retired General David Petraeus in Iraq. Wherever our de facto proconsul went, he appeared surrounded by mercenary guards, not American soldiers or Marines. With their dark glasses, beards, and steroid-advertisement biceps and pecs, the members of his security team seemed like Praetorians clearing the path for an emperor. Legal, efficient and, perhaps, even logical, the situation nonetheless felt profoundly un-American.

Can we imagine Washington, Grant, Pershing, Eisenhower or even the gravely flawed Westmoreland surrounding themselves with hired guns instead of entrusting themselves to their own soldiers?

Our wealth allows us to hire mercenaries. But their hiring signals rot within the state.

One may argue that the British Empire used hirelings to great effect (the First Indian War of Independence, aka the Sepoy Mutiny, notwithstanding) and the French finessed many a dubious endeavor by deploying expendable members of their Foreign Legion. But we’re not the French, nor are we pukka-sahib Brits taking tea on the Northwest Frontier. We’re Americans. And when it comes to our blithe acceptance of big business providing security forces to provide security to our forces, we need to examine our consciences, our commitment to our values, and the long-term strategic impact.

Meanwhile, the only state employing mercenaries more aggressively than the United States is the Russian Federation, which turned to Chechen mercenaries when its war with tiny Georgia stumbled and which, thereafter, promoted the Wagner Group of mass-murderers for hire. While the latter did not fare well when it foolishly confronted American forces head-on, suffering hundreds of casualties, it has elsewise proved a useful tool for Vladimir Putin, from eastern Ukraine, through Syria, to Libya—while killing wantonly.

We have not used mercenaries as combat forces. Yet. But it’s time to ask ourselves, before it’s too late, whether we want to uphold the tradition of the citizen-soldiers who won at Trenton—or hire the Hessians our ancestors defeated.

Ralph Peters’ most-recent book is Darkness at Chancellorsville.