- History

- Military

Russell Weigley, one of America’s leading military historians in the twentieth century, used Sherman’s 1864 scorched-earth March to the Sea that made “Georgia howl,” as an example of the American way of war. While there is some truth in Weigley’s description, he missed another aspect of the framework within which Grant and Sherman broke Confederate resistance and ended the Civil War: namely logistics and the problems that it raised for Union strategists in waging the war.

Too many historians have puzzled over why it took the North so long to bring the South to heel, when Union industrial power and population were so superior to that of the Confederacy. Simply put, the answer is that the Confederacy’s territorial expanse was immense: some 780,000 square miles, a territory greater in expanse than that of the territories of Britain, France, Spain, Germany, the Low Countries, and Italy combined. In the Eastern theater, logistics were not so much of a problem because the distances were considerably less. But the distances certainly were immense in the West, where Confederate guerrillas consistently destroyed the bridges and ripped up the rails on which Union armies depended for their supplies throughout 1862 and 1863.

After their crushing victory over the Army of Tennessee at Chattanooga in November 1863, Grant and Sherman confronted the fact that an advance on Atlanta, one of the key industrial centers in the Confederacy, was going to have to depend on supply lines that ran from Louisville to Nashville (185 miles), and from there on to Chattanooga (151 miles), where the advance on Atlanta (137 miles) would begin. In addition, much of the supplies for the advancing army group would come from factories in Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania, all a considerable distance from Louisville.

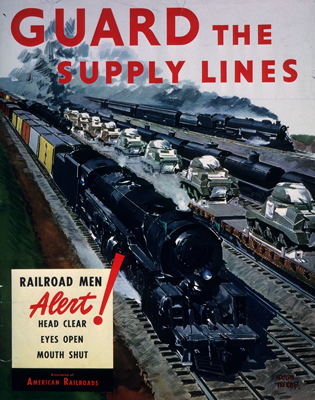

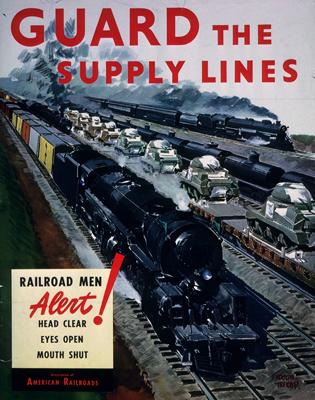

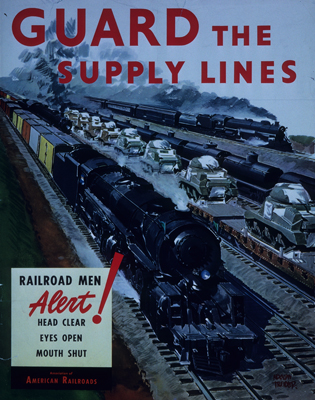

Immediately after their victory at Chattanooga, Grant, who remained as commander in the West until he assumed command of all Union armies and moved to Washington in early March 1864, and Sherman set about insuring that their supply lines in the West would not break for any period of time, as their armies moved ever deeper into the Confederacy. Thus, work began at once in rebuilding the entire rail system and depots that supported logistics from Louisville to Chattanooga. In February 1864, Daniel McCallum, one of the most experienced railroad managers in the East, received control of the massive restructuring. He created six separate sections with the requisite supply dumps of bridging materials, rail, and ties, with soldiers assigned to each section to rebuild any damage that Confederate raiders inflicted on the bridges and sections of the railroads. Major bridges received forts and garrisons for their protection. And a massive supply depot was created at Chattanooga, so that the same process of rebuilding and protecting the railroad would continue as Union armies advanced on Atlanta. Finally, McCallum persuaded Stanton, the Secretary of War, to contract with locomotive manufacturers to deliver 140 new locomotives over the summer to the system, along with 202 new freight cars every month.

The result was that Confederate raiders never managed to break Union supply lines to Chattanooga and then on to Atlanta for more than a single day at a time during the course of the campaign. In his memoirs, Sherman estimated that his armies required the logistical support of sixteen trains per day, each with ten freight cars with a total weight of 1,600 tons. That effort supported 100,000 men and 35,000 animals from May 1 to November 12, 1864, when Sherman cut his supply lines and began his March to the Sea. He added: “I reiterate that the Atlanta campaign was an impossibility without these railroads; and only then because we had the men and means to maintain and defend them, in addition to what was necessary to overcome the enemy.” In other words, without the logistical support, the Atlanta campaign would not have worked.

At present, the United States again confronts the same problem: the tyranny of distance and the fact that major military operations demand supplies. With much of the great infrastructure that supported U.S. forces throughout Asia and Europe during the Cold War abandoned, the American military face the fact that they must again project American power over continental and oceanic distances. In some respects, the current situation resembles that of 1941 and 1942. It does not represent a new strategic problem, rather logistics present problems for which there are no easy, simple answers. But it does represent the key to military effectiveness and has lain at the heart of the American way of war since the Civil War.