- Budget & Spending

- Economic

- Economics

- History

If you’re looking for a name to attach to the huge tax bite that was taken out of your last paycheck, try this one on for size: Beardsley Ruml.

Ruml was treasurer at R.H. Macy & Company during World War II. He was also an academic and chairman of the New York Federal Reserve Bank’s board of directors, a polymath so glittering that he stood out even in that era of big talkers. Ruml was so well known for his dinner party expositions that Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman made him a model for a character in The Man Who Came to Dinner.

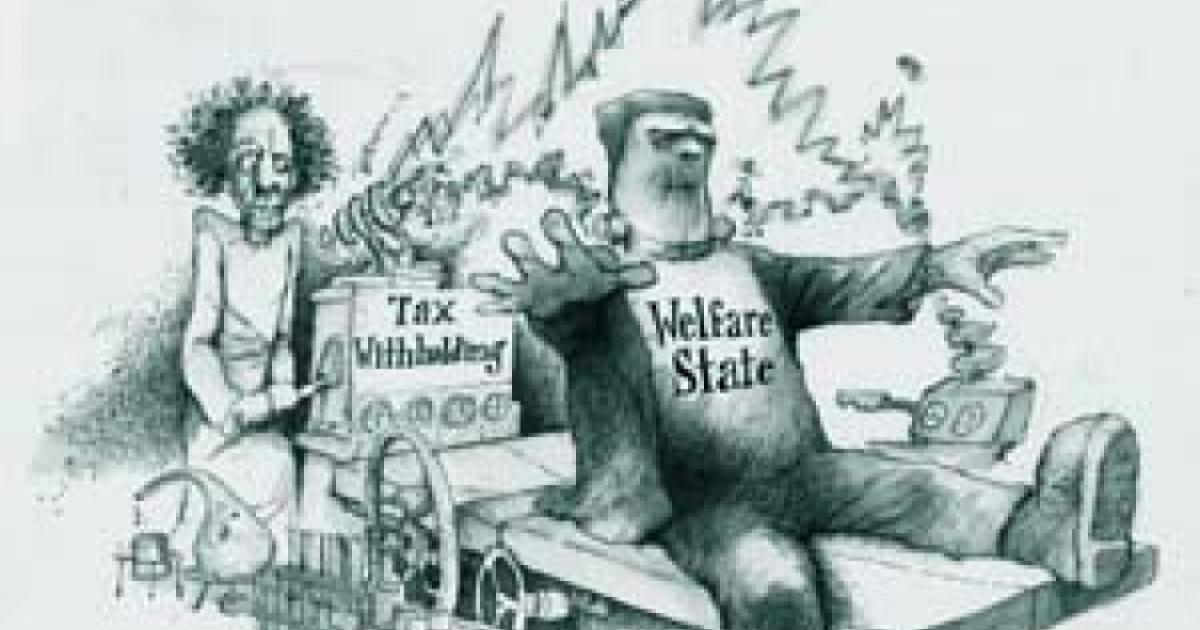

But it is Ruml’s role as New Deal spinmeister that keeps him in our thoughts today. He devised the legislation that gave us withholding as we know it. Today Americans give up more money in federal taxes than at any time except when the country was at war: 20.7 percent of the economy. Without withholding, it would be difficult to envision this scale of taxation persisting in a land born of a tax revolt. Indeed, without withholding the outsized government we have today would be hard to imagine.

Birth of the Mass Tax

The Ruml tale is worth recalling. In those years Washington was busy marshaling the forces of the American economy to halt Japan and Germany. In 1942 lawmakers raised income taxes radically, with rates that aimed to capture twice as much revenue as the previous year. They also imposed the income tax on tens of millions of Americans who had never been acquainted with the levy before. Chroniclers of the period say that the “class tax” became a “mass tax.”

But even in this most patriotic of moments, it was not evident that Americans were willing to pay the new tax. In those days, taxpayers sent one big check to the government. And as spring arrived in 1943, it appeared that many citizens might not ante up and file returns. Henry Morgenthau, the Treasury secretary, confronted colleagues about the nightmarish prospect of mass tax evasion: “Suppose we have to go out and arrest five million people?”

Enter Ruml, man of ideas. Like other retailers, he had observed that customers didn’t like big bills. They preferred installment payments, even if they had to pay interest to relieve their pain. So Ruml devised a plan, which he unfolded to his colleagues at the Fed and to anyone who would listen in Washington. The government would get business to do its work, collecting taxes for it. Employers would retain a percentage of taxes from workers every week and forward the money directly to Washington’s war chest. No longer would the worker ever have to look his tax bill square in the eye. He need never even see the money he was forgoing. Thus withholding as we know it today was born.

To tame resistance to the new notion, Ruml offered a powerful sweetener: The federal government would offer a tax amnesty for the previous year. It was the most ambitious bait-and-switch plan in America’s history.

Ruml advertised his project as a humane effort to smooth life in the disruption of the war. He noted that it was a way to help taxpayers out of the habit of carrying income tax debt, debt he characterized as “a pernicious fungus permeating the structure of things.”

Ruml’s genius did not lie in inventing withholding, already a known, if largely untried, tax concept. His genius lay in packaging so clever it provoked envy from his peers. Randolph Paul, a tax authority at Treasury, wrote distastefully that Ruml seemed to have convinced taxpayers he had found “a very white rabbit”—a magic trick—“which would somehow lighten their tax load.” Ruml called his program not “collection at source” or “withholding,” two technical terms that might put voters off, but “pay as you go,” a zippier name. Most important of all was the lure of the tax amnesty.

The policy thinkers of the day embraced pay as you go. This was an era in which John Maynard Keynes dominated economics, and Keynesians placed enormous faith in government, which they thought could end depressions, bring world peace, and build economies. The Ruml plan would give them the wherewithal to have their projects. The Keynesians also held that high taxes were crucial to controlling inflation.

CREATING THE MONSTER

Conservatives played their part in this drama. From a junior post at Treasury, a young economist named Milton Friedman helped plan the details of withholding. Later, Mr. Friedman called for the abolition of the withholding system. In their memoirs, Two Lucky People, Mr. Friedman and his wife, Rose, write that in the 1940s “we concentrated single-mindedly on the promotion of the war effort. We gave next to no consideration to any longer-run consequences. It never occurred to me at the time that I was helping to develop machinery that would make possible a government that I would come to criticize severely as too large, too intrusive, too destructive of freedom. Yet, that was precisely what I was doing.” One can almost hear Mr. Friedman sigh as he writes: “There is an important lesson here. It is far easier to introduce a government program than to get rid of it.”

We may have turned away from big government and the welfare state, but our enormous Washington bureaucracy and our bewildering tax code remain with us, unwieldy artifacts of an earlier era.

Although withholding was supposed to be a war measure, by 1945 there was a certain inexorability to the project. Even as the nation girded for VJ day, the big thinkers were laying out justification for expansive taxation in the postwar period. In 1945 Ruml himself published a book, Tomorrow’s Business, that described future national tax policy. Taxes, he said, were important “as an instrument of fiscal policy to help stabilize the purchasing power of the dollar” and “to express public policy in the distribution of wealth and of income, as in the case of progressive income and estate taxes.”

Early on, while the nation was still recovering from the shock of the war, there were several famous resisters. In the late 1940s, a Connecticut cable-grip maker named Vivien Kellems actually tried to create a movement to protest withholding. She refused to withhold for the hundred-odd employees of her company and challenged the Internal Revenue Service collectors in federal court. She even wrote a breathless volume of protest, titled Toil, Taxes and Trouble: “Under the hypnosis of war hysteria, with a pusillanimous Congress rubber-stamping every whim of the White House, we passed the withholding tax. We appointed ourselves so many policemen and with this club in our hands, we set out to collect a tax from every hapless individual who received wages from us.” Her protest earned her a modicum of respect in serious quarters. The journalist Harry Reasoner compared her battle to that of Gandhi and Martin Luther King. Most people, though, depicted her as a kook, and she spent her waning years until her death in 1975 holding forth at the soirees of the far-right fringe.

The feisty Adolph Coors family also tried to protest. The papers reported that Coors wanted to show workers the scope of the government take. The company gave them their full pay—without withholding—for two months. In the third month it took out three months’ worth of withholding. Yet Coors too soon abandoned its withholding experiment.

In recent decades it has become clear that Keynesianism is only window dressing for big government, and most policy leaders have ceased to see taxation as the principal monetary tool. From time to time, lawmakers, always Republicans, have questioned withholding. Ronald Reagan talked about challenging state withholding in his campaign for California governor—but did not follow through while in office. In this decade, House majority leader Dick Armey has pushed a plan to end withholding with his flat-tax proposal. Instead of the annual 1040 reconciliation, Americans would send the government a check every month, “rather like a monthly car payment.”

Still, withholding prevails, a testament to the force of Mr. Friedman’s wistful insight. We may have turned away from big government, the welfare state, and spending as a way of managing inflation, but our voluminous Washington bureaucracy and our bewildering tax code remain as unwieldy artifacts of an earlier era. It is a breathtaking contradiction and one that might not exist but for the powerful marketing skills of a wartime package man.