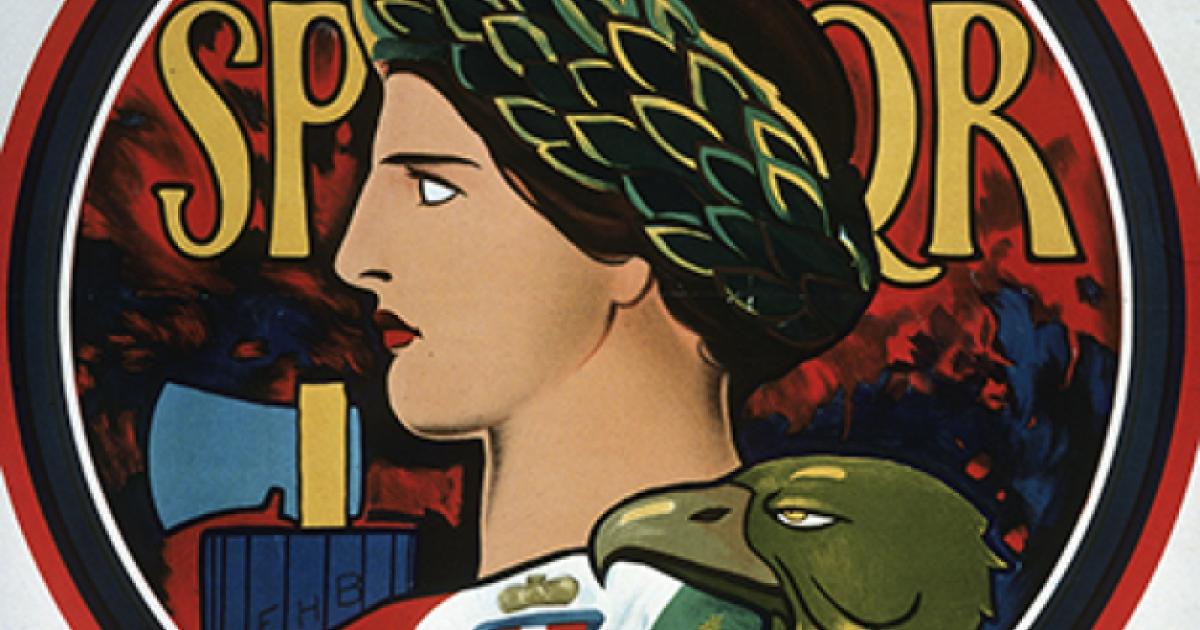

- History

By his own account, Julius Caesar was a brilliant soldier, and his masterful prose obscures his later misrule. Brutus didn’t draw his dagger because he was having a bad-toga day. In his time, Caesar set the pattern for repeated—all but countless—military moves against the Roman state and, consequently, rule by ill-suited emperors, with here and there a blood-sustained triumvirate or a doomed duopoly inserted between one-man reigns. The Roman Empire was not destroyed by barbarians, but by soldiers determined to fix it.

That pattern may be Rome’s most-relevant legacy.

Coups by military men—often quite junior in rank—long rattled history, with Napoleon Bonaparte’s takeover as a paramount example, but, paradoxically to our common thinking, they were statistically less common from the late-Medieval period through the generation that followed the Congress of Vienna. England’s Henry IV didn’t stage a military coup but a revolt of a disaffected aristocracy, the preferred method of regime change in his era. A condottiere might seize a baronage or, far more rarely, a duchy, but dynasties were rarely overthrown by upstarts lacking a blood claim to the throne: Fellow monarchs would not have it, and, of course, standing armies only came into their own in the seventeenth century.

Weak states attract strong men. Thus, the twentieth century saw a proliferation of coups by military leaders or charismatic figures backed by the military. The governance frustrations of the infant states formed during the great European-imperial retreat made coups all but inevitable, since struggling and fragile new governmental structures could not deliver the basic security and services of former colonial overlords, let alone fulfill fantastic expectations. Commonly, the newly organized military, however inept it may have been at fighting external enemies, was generally the best-organized, and the officer corps the best-educated, internal collective.

Not all of the last century’s coups were simple power grabs, of course. Often, soldiers seized power with a sincere intent (see Rome) to put an end to chaos and right the government…but weak institutions soon frustrated the man or men on horseback and the return to civilian rule was first postponed then set aside. Power not only corrupts but condemns the corrupted to cling to power to avoid retribution. And states uncertain of their national identities—particularly those containing ethnic groups that have been historical enemies—often end up under the rule of the tribal faction that dominates the military.

In our information-fractured twenty-first century, the pattern appears destined to continue: Tanks in the streets still trump Facebook. In recent weeks, military leaders have responded to public protests against presidents-for-life by removing the heads of state in Algeria and Sudan, but it remains to be seen how the generals will respond to continuing protests that want them to step aside, too.

Even in states where the military nods toward a return to civilian rule, as in Burma/Myanmar or Thailand, the military often remains the power not only behind but all around the throne. Generals remove their uniforms, but their loyalty remains to their epaulettes.

Nor are military coups always a phenomenon of the right wing. In the last century, left-wing rhetoric was more common when the armored cars rolled toward the seat of government. The most-recent case with strategic import was the Chavez revolt in Venezuela two decades ago, when a mid-grade paratrooper overthrew a structurally inequitable democracy. Now, ironically, the leaders of established democratic states hope for a military coup (that has as yet failed to materialize) against the disastrous Maduro regime that inherited Chavismo.

The maxim appears to be that we, the great democracies, decry military coups—except when they suit us. Indeed, the deadly incompetence of the Maduro regime should end for the sake suffering Venezuelans, but a stamp of approval on one coup inspires another.

There are no easy answers, there are no inevitable outcomes. But our new century already looks (ironically, given the Aquarian promises of the internet age) a lot like the last one.

Hail Caesar! Beware the Ides of March.

Ralph Peters’ latest book, Darkness at Chancellorsville, will be published on May 21st.