- International Affairs

- Key Countries / Regions

- Middle East

- Security & Defense

- US Defense

- US Foreign Policy

- Terrorism

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

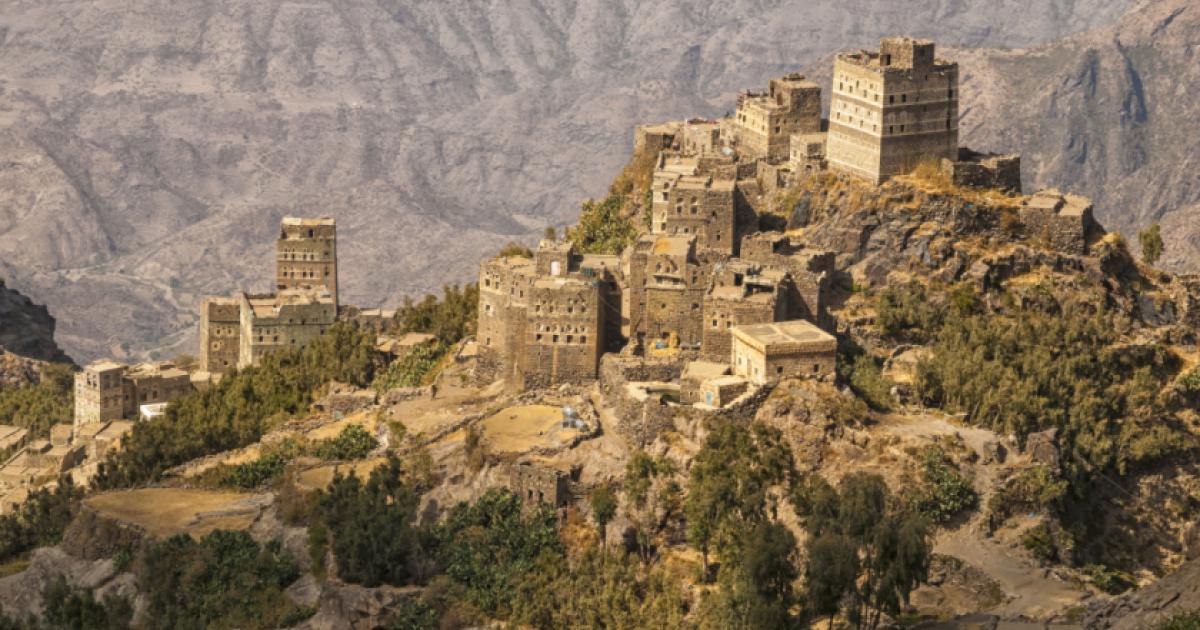

The conflict in Yemen is poorly understood in the United States. The general view in policy and government circles is that Saudi Arabia is the principal cause of the crisis, and that if the Saudis can be made to stop their military campaign against the Houthi rebel movement, the war would end quickly. Furthermore, this conflict is often mistakenly characterized as one between the regional powers of Saudi Arabia and Iran or one between Sunnis and Shia Muslims. It is in fact first and foremost a civil war, the most recent of several wars between Yemenis that began in 1962. Thus, it is internal dynamics that drive Yemenis to fight each other, and this war is unlikely to end quickly no matter what Saudi Arabia does or is made to do. After considerable resistance and perhaps willful naïveté, Washington finally appears to be accepting this reality.

Upon taking office, the Biden administration held the view that Riyadh was the principal culprit in the Yemeni war and therefore sought to exert pressure on the Kingdom to end its military intervention. This is a view that many Democrats in Congress also hold. Biden immediately reversed the Trump administration’s designation of the Houthis as a terrorist organization, announced a general review of US-Saudi relations, ostracized the Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman (MBS), and declared a moratorium on the sale of offensive weapons to the Kingdom. In other words, Biden believed that America’s pressure on Riyadh would initiate peace talks between the various Yemeni and regional actors in this conflict and that the Houthis would stop their military assault on Ma’rib, a strategically important city in the east of the country. Washington’s moves were indeed soon followed by a Saudi offer of a ceasefire and the lifting of the blockade, something MBS had been preparing for months because he has finally realized the quagmire he is in. Yet, rather than come to the negotiating table, the Houthis--just like the Taliban--doubled down on their military attacks, both on Ma’rib and by firing ballistic missiles and drones inside Saudi territory. Why did the Houthis react aggressively in this way and why do they continue to seem uninterested in ending the war? To understand the Houthis’ rationale, one has to delve into Yemen’s history and the particular ideology and program of this radical Islamist movement.

Who are the Houthis and what do they want?

The Houthis are a revolutionary Muslim Shiite group that captured the capital Sanaa in September 2014, ousting the internationally recognized government of Yemen, and then proceeded to attempt a military takeover of the entire country. They constitute a minority group, whose core members claim to be descendants of the Prophet Muhammad (aka sayyids). The movement emerged in the early 2000s and fought six brutal wars with the central government from 2004-2010, and these left large swaths of the north devastated and a humanitarian disaster zone.

The Houthis’ ideology is centered around the teachings of their founder, the late Husayn al-Houthi (d. 2004), who advocated the domination of the country by the sayyids as well as the radical transformation of its society according to an idiosyncratic interpretation of Islamic texts and tradition. Houthi’s ideology consists of a combination of anti-imperialist and anti-American rhetoric (“Death to America, Death to Israel”) with a radical Islamist vision of a world ruled by a descendant of the Prophet. This leader--who today is embodied by the movement’s leader whose name is Abd al-Malik al-Houthi--claims supreme authority over all Muslims around the world. He is a caliph in all but name and is referred to by his followers as the “Banner of Guidance” (‘alam al-huda). In some sense, the Houthis are similar to the Iranian Islamist revolutionaries led by Ayatollah Khomeini in 1979, but they have a distinctly more radical ideology about transforming society and Muslim religious belief and practice. Indeed, the Houthis’ revolutionary program can be compared to the Vietcong or even the Khmer Rouge in its ambition and scale although, of course, not in content.

Despite being a minority, perhaps some 5 to 10 percent of Yemen’s population, the Houthis are the best organized and ideologically motivated group in Yemen. These characteristics explain their military success and ascendancy, which they are not willing to give up until they have fully established themselves in power. But the Houthis did not emerge in a vacuum. Their rise should be seen in light of the systematic social and religious discrimination of the sayyids (i.e., Muhammad’s descendants) since 1970 by the government in Sanaa as well as the appalling governance and corruption of the regime of the late dictator Ali Abdullah Salih, the country’s president from 1978 until 2011. These are the two principal features of the context that have helped generate the chaos we are witnessing in Yemen today. On the one hand, the Houthis seek to make the sayyids the dominant political group and a member of their own family the supreme ruler, thus guaranteeing that they will never be marginalized and persecuted again. On the other hand, it is President Salih’s willfully bad governance that destroyed the nation’s institutions, fragmented its society and created the deep political, regional and identitarian cleavages that now fuel the civil war. Unfortunately, there are no quick fixes for such long-gestating structural problems.

Saudi Arabia and the Houthis

The Saudis somewhat mistakenly see the Houthis as a purely Iranian proxy akin to Hezbollah in Lebanon. The Houthis are indeed close allies of Iran and some of their ideological inspiration comes from Khomeini’s revolutionary ideas. Also, they no doubt coordinate their strategy and even specific attacks on Saudi Arabia with Tehran. Yet, the Houthis are a deeply rooted social and political phenomenon of the Yemeni scene and have an agenda that is ultimately about achieving local goals, such as rule by the sayyids over other Yemenis. However, the Saudis were not able to tolerate what they perceived to be Iranian influence in their southern neighbor, and therefore decided in March 2015 to enter the Yemeni civil war by leading a military coalition against the Houthis with the aim of reinstating the internationally recognized Yemeni government. Riyadh has not committed ground troops and has mostly engaged the Houthis in air strikes, no doubt because it knows from past experience and history that Yemen, like Afghanistan, is an impossible place in which to win wars decisively. The war against these rebels is now in its seventh year and has been brutal, involving a blockade of Houthi-controlled ports and airports, and this has greatly exacerbated the country’s humanitarian crisis. Millions are malnourished, cholera is widespread and the various militias, especially the Houthis, use food and fuel as instruments of coercion and a source for revenue generation.

Despite overwhelming military superiority, the Saudis along with their Yemeni allies have been unable to defeat the Houthis, who now control much of north Yemen and rule over two thirds of the population. Should Ma’rib be captured several million more Yemenis would fall under Houthi rule and with this their control over the north will be complete. One reason for the success of the Houthis is the disunity and infighting among the several Yemeni factions arrayed against them. Another is the superior fighting spirit and ideological motivation of the Houthis. They have framed the war as one against foreign domination, appealing to a strong sense of Yemeni nationalism. Sooner or later both the Saudis and their Yemeni allies will have to accept that the Houthis are here to stay, will have to play a dominant political role and some form of accommodation with them will become necessary. It is unclear how long this will take or what role the United States can play in helping bring this realization about.

The US Role

It is not obvious that the US can play an effective role in helping end this conflict. Within Yemen, America’s influence is negligible since it has little leverage over any of the various factions. Washington can try to engage Iran on Yemen through the ongoing negotiations over the resumption of the nuclear agreement or the so-called Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). Iran certainly has influence over the Houthis but until now Tehran has benefited from the war since it has been costly and hugely frustrating for the Saudis, their regional rival. As such, it is not in Iran’s interest to see the war end and it is unlikely it will use its influence with the Houthis to tone down hostilities. The only effective leverage the US has is over Saudi Arabia, and the Saudis are indeed keen to extricate themselves from the war, but not at any cost. A Yemen that is dominated by hostile Houthis who are constantly firing missiles and drones at the Kingdom is not an acceptable outcome for Riyadh nor should it be for Washington.

One possible avenue to test the possibility of bringing a cessation of hostilities in Yemen, if not an actual end to the war, is for the US to suggest to the Saudis that they make an offer that the Houthis, and other Yemenis, cannot refuse. For example, this could entail an immediate and unilateral ceasefire, the lifting of the blockade, substantial and yearly development and reconstruction funds, over say a decade, to see that Yemen is rebuilt, and, finally, a promise to make Yemen a member of the Gulf Cooperation Council. Such a generous and comprehensive offer, if made, would make it clear to all Yemenis that their long-term interests lie in ending the war and joining with and benefitting from the rich petro-states of Arabia. If this offer is turned down, then the US and other states in the region will have to contend with and contain the effects of a war in Yemen that is unlikely to end anytime soon.

Bernard Haykel is a Professor of Near Eastern Studies and Director of the Institute for Transregional Study of the Contemporary Middle East, North Africa, and Central Asia at Princeton University.