- Economic

- Contemporary

- The Presidency

- History

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

With the coming of the Great Depression in the 1930s, a sharp increase in protest and anticapitalist sentiment threatened to undermine the existing political system and create new political parties. The findings of diverse opinion polls, as well as the electoral support given to local radical, progressive, and prolabor candidates, indicate that a large minority of Americans were ready to back social democratic proposals. It is significant, then, that even with the growth of class consciousness in America, no national third party was able to break the duopoly of the Democratic and Republican Parties. Radicals who operated within the two-party system were often able to achieve local victories, but these accomplishments never culminated in the creation of a sustainable third party or left-wing ideological movement. The thirties dramatically demonstrated not only the power of America’s coalitional two-party system to dissuade a national third party but also the deeply antistatist, individualistic character of its electorate.

|

|

Illustration by Taylor Jones for the Hoover Digest. |

The politics of the 1930s furnishes us with an excellent example of the way the American presidential system has worked to frustrate third-party efforts. Franklin D. Roosevelt played a unique role in keeping the country politically stable during its greatest economic crisis. But he did so in classic or traditional fashion. He spent considerable time wooing those on the left. And though many leftists recognized that Roosevelt was trying to save capitalism, they could not afford to risk his defeat by supporting a national third party.

The Nation Shifts to the Left

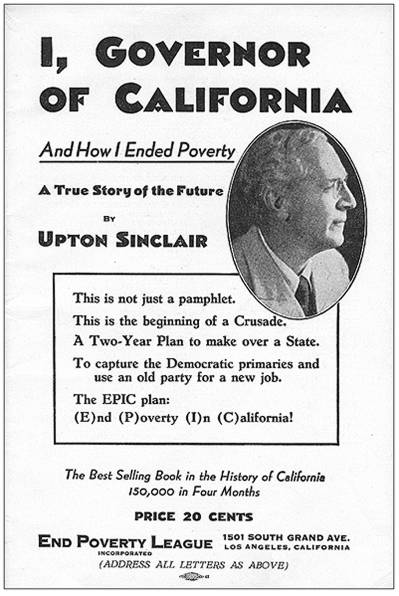

Powerful leftist third-party movements emerged in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and New York. In other states, radicals successfully advanced alternative political movements by pursuing a strategy of running in major-party primaries. In California, Upton Sinclair, who had run as a Socialist for governor in 1932 and received 50,000 votes, organized the End Poverty in California (EPIC) movement, which won a majority in the 1934 Democratic gubernatorial primaries. He was defeated after a bitter business-financed campaign in the general election, though he secured more than 900,000 votes (37 percent of the total). By 1938, former EPIC leaders had captured the California governorship and a U.S. Senate seat.

In Washington and Oregon, the Commonwealth Federations, patterning themselves after the social democratic Cooperative Commonwealth Federation of Canada, won a number of state and congressional posts and controlled the state Democratic Parties for several years. In North Dakota, the revived radical Nonpartisan League, still operating within the Republican Party, won the governorship, a U.S. Senate seat, and both congressional seats in 1932 and continued to win other elections throughout the decade. In Minnesota, the Farmer-Labor Party captured the governorship and five house seats. Wisconsin, too, witnessed an electorally powerful Progressive Party backed by the Socialists.

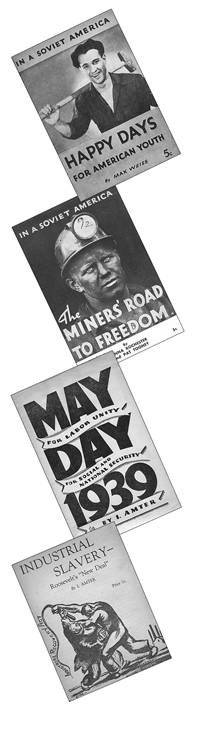

The Socialist and Communist Parties grew substantially as well. In 1932 the Socialist Party had 15,000 members. Its electoral support, however, was much broader, as indicated by the 1932 presidential election, in which Norman Thomas received close to 900,000 votes, up from 267,000 in 1928. The Socialist Party’s membership had increased to 25,000 by 1935. As a result of leftist enthusiasm for President Roosevelt, however, its presidential vote declined to 188,000 in 1936, fewer votes than the party had attained in any presidential contest since 1900. The Communist Party, on the other hand, backed President Roosevelt from 1936 on, and its membership grew steadily, numbering between 80,000 and 90,000 at its high point in 1939. Communists played a role in “left center,” winning electoral coalitions in several states, notably California, Minnesota, New York, and Washington.

|

|

A 1933 booklet promotting Upton Sinclair’s run for California governor. |

National surveys suggest that the leftward shift in public opinion during the 1930s was even more extensive than indicated by third-party voting or membership in radical organizations. Although large leftist third parties existed only in Minnesota, New York, and Wisconsin, three Gallup polls taken between December 1936 and January 1938 found that between 14 and 16 percent of those polled said they would not merely vote for but “would join” a Farmer-Labor Party if one was organized. Of those interviewees expressing an opinion in 1937, 21 percent voiced a readiness to join a new party.

Co-opting the Left

If the Great Depression, with all its attendant effects, shifted national attitudes to the left, why was it that no strong radical movement committed itself to a third party during these years? A key part of the explanation was that President Roosevelt succeeded in including left-wing protest in his New Deal coalition. He used two basic tactics. First, he responded to the various outgroups by incorporating in his own rhetoric many of their demands. Second, he absorbed the leaders of these groups into his following. These reflected conscious efforts to undercut left-wing radicals and thus to preserve capitalism.

Franklin Roosevelt demonstrated his skill at co-opting the rhetoric and demands of opposition groups the year before his 1936 reelection, when the demagogic Senator Huey Long of Louisiana threatened to run on a third-party Share-Our-Wealth ticket. This possibility was particularly threatening because a “secret” public opinion poll conducted in 1935 for the Democratic National Committee suggested that Long might get three to four million votes, throwing several states over to the Republicans if he ran at the head of a third party. At the same time several progressive senators were flirting with a potential third ticket; Roosevelt felt that as a result the 1936 election might witness a Progressive Republican ticket, headed by Robert La Follette, alongside a Share-Our-Wealth ticket.

To prevent this, Roosevelt shifted to the left in rhetoric and, to some extent, in policy, consciously seeking to steal the thunder of his populist critics. In discussions concerning radical and populist anticapitalist protests, the president stated that to save capitalism from itself and its opponents he might have to “equalize the distribution of wealth,” which could necessitate “throw[ing] to the wolves the forty-six men who are reported to have incomes in excess of one million dollars a year.” Roosevelt also responded to the share-the-wealth outcry by advancing tax reform proposals to raise income and dividend taxes, to enact a sharply graduated inheritance tax, and to use tax policy to discriminate against large corporations. Huey Long reacted by charging that the president was stealing his program.

President Roosevelt also became more overtly supportive of trade unions, although he did not endorse the most important piece of proposed labor legislation, Senator Robert Wagner’s labor relations bill, until shortly before its passage.

Raymond Moley, an organizer of Roosevelt’s “brain trust,” emphasized that the president, through these and other policies and statements, sought to identify himself with the objectives of the unemployed, minorities, and farmers, as well as “the growing membership of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), Norman Thomas’ vanishing army of orthodox Socialists, Republican progressives and Farmer-Laborites, Share-the-Wealthers, single-taxers, Sinclairites, Townsendites [and] Coughlinites.”

Destroying the Third-Party Threat

Beyond adopting leftist rhetoric and offering progressive policies in exchange for support from radical and economically depressed constituencies, President Roosevelt also sought to recruit the actual leaders of protest groups by convincing them that they were part of his coalition. He gave those who held state and local public office access to federal patronage, particularly in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and New York, where strong statewide third parties existed. Electorally powerful non-Democrats whom Roosevelt supported included Minnesota governor Floyd Olson (Farmer-Labor Party), New York City mayor Fiorello La Guardia (American Labor Party), and Nebraska senator George Norris (Independent), as well as Wisconsin governor Philip La Follette and his brother, Senator Robert La Follette Jr. (both Progressive Party).

|

|

Booklets from the American Communist Party from the 1930s. |

This strategy had an impact. In 1937, Philip La Follette’s executive secretary told Daniel Hoan, the Socialist mayor of Milwaukee, that a national third party never would be launched while Roosevelt was “in the saddle,” because Roosevelt had “put so many outstanding liberals on his payroll [that] . . . any third party movement would lack sufficient leadership.” The president told leftist leaders that he was on their side and that his ultimate goal was to transform the Democratic Party into an ideologically coherent progressive party in which they could hope to play a leading role. A few times he even implied that, to secure ideological realignment, he personally might go the third-party route, following in the footsteps of his cousin Theodore Roosevelt.

Franklin Roosevelt ran his 1936 presidential campaign as a progressive coalition, not as a Democratic Party activity. Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. has described Roosevelt’s tactics as follows:

As the campaign developed, the Democratic party seemed more and more submerged in the New Deal coalition. The most active campaigners in addition to Roosevelt—[Harold] Ickes, [Henry] Wallace, Hugh Johnson—were men identified with the New Deal, not with the professional Democratic organization. Loyalty to the cause superseded loyalty to the party as the criterion for administration support. . . . It was evident that the basis of the campaign would be the mobilization beyond the Democratic party of all the elements in the New Deal coalition—liberals, labor, farmers, women, minorities.

Roosevelt was reelected by an overwhelming majority in 1936. Yet his second term proved much less innovative than his first. This was due, in part, to several Supreme Court decisions during 1936 striking down various New Deal laws as unconstitutional and the president’s subsequent inability to mobilize popular protest against the Court. Reacting to a perceived shift in the public mood to the right, particularly from 1938 on, Roosevelt substantially reduced his reform efforts. The change, however, did not lead to a loss of leftist support. The Communist Party, following its Soviet-dictated Popular Front policy, actively opposed efforts in a number of states to create independent radical anti-Roosevelt political campaigns. Sounding like a moderate liberal group, it increased its membership, formed large front groups, and generally expanded its influence in the labor movement.

|

The economic crisis of the 1930s presented American radicals with their greatest opportunity to build a third party since World War I, but the constitutional system and the brilliant way in which Franklin Delano Roosevelt co-opted the left prevented this. |

On the assumption that the 1937–38 recession had undermined Roosevelt’s prestige, Wisconsin governor Philip La Follette attempted in 1938 to create a new third party, the National Progressives of America. The president responded with a renewed effort to co-opt such opposition.

The midterm elections in November 1938, however, made it unnecessary for President Roosevelt to react to a possible electoral threat from the left. Both the Wisconsin Progressive Party and the Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party suffered crushing defeats, losing most of their congressional seats, and Republicans badly defeated both Philip La Follette in Wisconsin and Elmer Benson in Minnesota in their gubernatorial reelection campaigns. Although unhappy about the Republicans’ gaining 81 seats in the House, 8 seats in the Senate, and 13 governorships, the president noted that some good things had occurred: “We have on the positive side eliminated Phil La Follette and the Farmer-Labor people in the Northwest as a standing Third Party Threat.”

Conclusion

Although party divisions became more class based, efforts to build a national left-wing third party failed. This cannot be explained by any absence of protest or popular support for radical efforts. Several developments attest to the growth of class conflict and the vigor of anticapitalist feeling that resulted from the Great Depression: mass demonstrations of the unemployed, the aggressive tactics and radical views of farm groups, widespread militancy and disdain for private property exhibited by many groups of workers, leftist views expressed by large minorities in the opinion surveys, and, finally, the strong and disparate electoral support given to leftist third parties and organized factions within the major parties in New York, Washington, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota, Oregon, and California.

|

Franklin Roosevelt succeeded in undercutting the growth of left-wing political movements in the mid-1930s by adopting much of the rhetoric of the left and co-opting many of its leaders. |

President Roosevelt recognized that the long-range interests of his coalition and the Democratic Party were best served by encouraging radical groups, whether inside or outside the party, to feel as though they were part of his political entourage. Thus, as we have seen, he showed a willingness to endorse local and statewide third-party or independent candidates and give them a share of federal patronage. In return, they were expected to support the president’s reelection.

Time and again between 1935 and 1940, meetings to lay the basis for a national third party went awry because those involved recognized that the bulk of their constituencies favored reelecting the president. And, in the last analysis, most radical, labor, and minority-group leaders supported the president as well. Certainly these leaders objected to particular Roosevelt policies, to his compromises with conservatives, and, in some cases, to his refusals to back their group or organization in some major conflict. Nevertheless, they concluded that a government in which they could play a part, which had shown some responsiveness to their concerns, and which acknowledged their importance was far preferable to a Republican administration with strong links to business.

|

The fact that left-wing parties did not make significant inroads during the Great Depression dramatically demonstrated not only the power of America’s coalitional two-party system to dissuade a national third party but also the deeply antistatist, individualistic character of its electorate. |

The economic crisis of the 1930s was more severe in the United States than in any other large society except Germany. It presented American radicals with their greatest opportunity to build a third party since World War I, but the constitutional system and the brilliant way in which Franklin Delano Roosevelt co-opted the left prevented this. The Socialist and Communist Parties saw their support drop precipitously in the 1940 elections. America emerged from the Great Depression as the most antistatist country in the world.