- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- World

- History

Libya?

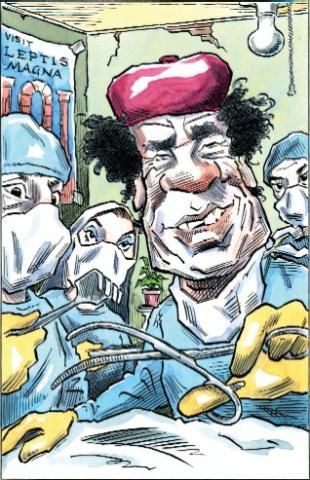

Most are rightly taken aback at the thought. But I was intrigued when an educational cruise line invited me to lecture this past April on the classical antiquities of Libya—or, more properly, “The Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya the Great,” which since 1986 has been Colonel Muammar Gadhafi’s name for his ancestral country.

As petroleum engineers will point out endlessly in the lobby of the Corinthian, Tripoli’s only Western hotel, Libya is both huge and tiny. Slightly larger than Alaska, it is likewise relatively empty of people and almost unexplored. Oilmen like both. We forget that, for all its notoriety, Libya, given the dearth of water and the nearness of the desert to within 50 miles of the coastline, has fewer than 6 million people—one of the smallest populations of any Arab nation.

The Roman ruins at Leptis Magna and Sabratha are among the most impressive in the Mediterranean. And they are relatively untouched and unseen because Gadhafi expelled most Europeans soon after his 1969 socialist revolution. An earlier bloody North African officer who staged a coup, Septimus Severus, was born in a.d.146 at Leptis. His largesse to his native city—an enormous basilica, triumphal arches, a vast harbor and lighthouse—together with the booming commerce of the imperial eastern Mediterranean during Rome’s first attempt at globalization, made these North African coastal settlements among the most vast and opulent of the empire. The dry climate and sparse nomadic population have for centuries ensured the preservation of Libya’s “cities in the sand” long after the Vandals looted them. They remain haunting today in their grandeur, more like recent ghost towns than ancient ruins.

It’s also impossible not to have a perverse curiosity about the proverbially lunatic present-day Libya. It is not just its 35-year history of sponsoring African revolutionaries, terrorist operatives in Europe, and hit squads sent after Libyan dissidents. There are stranger, North Korea–like tales. Many there still remember the colonel’s 1977 fiat that all Libyans, even Tripoli’s 1 million urban residents, were to raise chickens; or his call to gather up all of Jamahiriya’s Western musical instruments and burn them en masse; or his offer of $5,000 to any Libyan who would marry a sub-Saharan black African to further Gadhafi’s own reputation as the great African unifier.

But even more bizarre were the reports that after 2003, Gadhafi had abruptly liberalized his police state. By the time of my visit in spring 2006, he was finishing his byzantine negotiations with the U.S. State Department, which would get rid of his weapons of mass destruction, reopen embassies in both capitals, and allow Libyans and Americans to visit each country freely. Gadhafi had even appointed an American-educated economist as his new prime minister, and he was eager for the planned renewed relations with the United States to evolve into real friendship—hence the limited number of visas now accorded to the new generation of American visitors.

I had a few reservations, of course, about visiting Gadhafi’s Libya, having criticized Arab autocracies frequently in print, both here and abroad, and having read long ago the colonel’s bizarre Green Book and its plans of making Libyans into new “partners” of his authoritarian socialist state, rather than “slaves” to Western-style capitalist democracy. That pamphlet—a mishmash of Nasserite, socialist, Islamic, Bedouin, and authoritarian pop philosophizing—was Libya’s Robert’s Rules of Order for a large cadre of aging revolutionary committees and increasingly worried security services.

Nor is it quite as easy to enter and travel inside Libya as its new generation of reformers envisions. Moreover, there was only an American interest section at the Corinthia hotel, no embassy, so travelers until recently were more or less on their own. And I had my own complications: Because of a long-planned speaking tour in the American South, I would have to fly late and alone into Tripoli to meet the cruise ship from Italy—hopefully still docked at Leptis—and then trust that the visa that allowed me to enter only by air would also permit departure by sea to Carthage in Tunisia. Then there was a minor health problem of intermittent abdominal aching and nausea that had persisted for over a year, despite a physician’s diagnosis of “bad food” or perhaps yet another kidney stone. Still, I figured I would stop the morning sit-ups and the Libyan holiday would be fine.

After receiving my visa from a Canadian go-between—by spring of 2006, our government still had not allowed any Libyan consular officials inside the United States—I landed in Tripoli in mid-April, met my government-supplied travel minders, and began asking rapid-fire questions about Libya, ancient and modern. Gadhafi’s portrait, splashed over a background of his trademark green, still looms everywhere, albeit now surrounded with Coke and Sony billboards. The colonel is also often superimposed on a verdant map of Africa to remind Libyans that his geriatric revolutionary socialist movement still exudes pan-African zeal.

| Rome’s first attempt at globalization made Libya’s coastal settlements among the most vast and opulent of the empire. Modern isolation has left their ruins mostly untouched and unseen. |

When I arrived, Lionel Richie had just finished a rock concert at Gadhafi’s former residence, commemorating the 20th anniversary of Ronald Reagan’s “crime” of bombing Tripoli. Between songs, Richie offered prayers for Gadhafi’s deceased “daughter,” killed by the American bombs (most think that Gadhafi adopted her posthumously). Most Libyans I talked with, though, seemed indifferent to the celebration, griping instead about all the money going “south” to Third World con artists in sub-Saharan Africa still masquerading as sixties-style communists and national liberationists. They were much more interested in the world to the north, asking whether George Bush would reply seriously to Gadhafi’s bold peace feelers and follow the Europeans back into Libya.

As my minders drove me the next few days back and forth through the drab city, I was struck that a nation that could export 1.6 million barrels of oil a day (bringing in over $40 billion in annual income at recent prices) could not yet asphalt all the dusty back ways of Tripoli’s suburbs or fix the gargantuan potholes on the main thoroughfares. But read the Green Book; then the general poverty of the country seems the logical manifestation of Gadhafi’s zealous vows to eliminate most private property, end a market economy and its “parasitical” middle class, shrink the professional elite, and ensure cradle-to-grave subsidies for everyone else—all the while supporting “liberation” movements from South Africa to Northern Ireland.

| Most Libyans I talked with—and how they love to talk, mostly politics— griped about all the money going “south” to Third World con artists in sub-Saharan Africa still masquerading as sixties-style Communists and national liberationists. They were much more interested in the world to the north. |

The first few days went well. The intrigue of Leptis Magna is not just that it spreads almost endlessly through dunes and grass-covered hills, with the pristine Mediterranean shore at its back, but that most of its remains, like Colonel Gadhafi’s oil, still lie under the sand. Skeletons of old Italian cart rails and rusted tools are scattered around the site, the detritus of Mussolini’s once-grand schemes to showcase his Roman forebears’ first civilizing mission to tame North Africa. Western archaeologists, nursed on the dated excavation reports of the 1960s, have pined to return for four decades. For the classical scholar, Leptis of the magnificent mosaics is like a mine in the mother lode, shut down when its richest vein was scarcely tapped.

Libyans seem to talk nonstop. It’s as if they have been jolted from a long sleep and are belatedly discovering, thanks to their newfound Internet, satellite television, and cell phones—many carry two to ensure that they are never out of service from competing companies—that there is a wide world outside dreary Tripoli and beyond the monotonous harangues of government socialists on the state-owned TV and radio stations.

They talked about their new gadgetry, and much else, with infectious optimism. As one hopeful Libyan travel entrepreneur with friends in the government explained, there might be some irony after all to Libya’s long, self-imposed insularity. Yes, he conceded, foreign investment declined. Oilmen left. Petroleum production nose-dived from more than three million barrels to never more than two million. But there was a silver lining: Did all that not have the effect of saving Libya’s precious resource to await the return of the present sky-high prices? Yes, Libya had banked a sort of strategic oil reserve that now was to be tapped at its most opportune moment. Yes, it was Libya’s grand strategy to deny Westerners its petroleum treasure for years, until they finally came around to pay what it was really worth!

| Reminded of the 1988 bombing of Pan Am Flight 103, Libya’s vast weapons-of-mass-destruction program, the efforts to cause havoc in Chad, and so on, Libyans looked away as if the rude stranger had ruined a long-planned reunion celebration. |

I was not sure that it did not make a certain sort of post facto sense. Libyans gushed on that geologists may have just scratched the surface of their country’s known oil and gas reserves. The petroleum alone under the desert was already pegged at 40 billion barrels—with 60 percent of the country still uncharted. To add to their euphoria, I did some quick math. At a theoretical $70 a barrel, the likely climb back to more than three million barrels a day could mean an extra $35 billion a year in windfall Libyan petro-profits.

Libyans have surprisingly little anger over these four squandered decades. Instead, they kept voicing the same themes—including that the past opportune “conservation” soon would bring dividends to the magnificent ruins at Sabratha and Leptis as well. “Isn’t it true, Dr. Hanson,” they often queried, “that our antiquities are the best in the Mediterranean? Because few have seen them, they are mysterious and not so damaged from tourism—and now just waiting for you in the West to work with us to rediscover them. The sand at Leptis is like the sand of the desert: Both have been keeping our ruins and oil safe until now.”

The tiny world of classics, of course, eagerly awaits the reopening of Leptis Magna. But more important, there are rumors of Italian and Maltese tourist pavilions and more Corinthia-like seaside hotels to come—the Mediterranean coastline outside Tripoli is as beautiful as it is pristine. Over lunches, the Libyan tourist officials traded guesses on the numbers of European cruise ships that would soon queue up outside Libya’s soon-to-be-built tourist docks. They would unload myriad shoppers laden with euros and eager for Berber folk arts and crafts—culture’s counterpart to the proposed enormous liquefied natural gas plants that would supply Europe’s energy appetite across the Mediterranean.

But always framing these conversations were two more melancholy themes that led to sudden embarrassing silences—the United States’ new Middle East “democratization” policy and Libya’s recent history. Would the United States warm to Libya’s bold opening without impossible preconditions? Were not Libya’s oil, antiquities, and goodwill enough to make everyone forget the unfortunate shared past? The last sentiments were always in more hushed tones, given the fear of ubiquitous government informers in and outside our small circle.

When I went over the old litany—the 1988 bombing of Pan Am Flight 103, Libya’s vast weapons-of-mass-destruction program, the efforts to cause havoc in Chad, the trumped-up capital convictions of Bulgarian nurses falsely charged with deliberately injecting Libyan children with HIV, the recent plan to assassinate Saudi Crown Prince Abdullah after he traded slurs with Gadhafi at an Arab League summit in 2003, and on and on—Libyans looked away as if the rude stranger had ruined a long-planned reunion celebration.

Among foreigners, a constant topic is the mystery over Gadhafi’s opening of the country in 2004 and his pledge to give up his WMD arsenal. American liberal pundits ridicule the administration’s claim that Saddam Hussein’s capture, and especially the end of his sons Uday and Qusay, prompted the colonel’s desire to avoid the same fate for his family—proof, as it were, of the success of the Bush Middle East policy. But perhaps it is true—at least that is what Gadhafi supposedly told Italian prime minister Berlusconi in a phone conversation: “I will do whatever the Americans want, because I saw what happened in Iraq, and I was afraid.”

Libyans, of course, prefer to put a diplomatic spin on the conversion without assigning causation: “You Americans,” they told me, “should call it a windfall: you went to the wrong palace to find your WMD by force but, by our goodwill, found it here nonetheless—and in peace.”

But there were other reasons for change as well. At least three of Gadhafi’s eight children are European-educated and reportedly have persuaded their father to emulate what they have seen and enjoyed abroad.

| I had done some research on Libya and remembered coming across an old Wall Street Journal piece that referred in passing to Libya’s hospitals as “dirty death traps.” But my medical emergency left me no choice. |

There is also real Libyan disgust over the billions squandered on revolutionary—mostly terrorist—movements the world over, especially the largesse given to the African insurrectionists. As one minor Libyan official put it to me, “They all cut deals with you in the West—the African National Congress, the IRA, Sandinistas, Liberians, and the Palestinians. Now you think these former killers are OK again, but not us—who had less blood on our hands. So why should we not deal, too?” I passed over the probable falsity of that claim and instead reminded him of rumors that Al-Qaeda-backed terrorists see Gadhafi’s quasi-secular socialism as heresy and have been trying in earnest to assassinate him—groups with such typical bumper-sticker nomenclature as the Islamic Movement of Martyrs, Libyan Jihad Movement, and Islamic Movement for Change. Apparently the enemy of our enemies is to be our friend after all.

More concerns followed. There are a million Egyptian guest workers in Libya, many of them there illegally. In Egyptian circles, pan-Arabist talk of the old Nasserite notion of a United Arab Republic still abounds, a “reunification” perhaps of part of Libya’s eastern tribal zones with an Egypt without oil—the same sort of nonsense that Libya once proposed to Tunisia. In this context, my Libyan companions voiced a weird sort of nostalgia for the old American Wheelus Air Force Base, vacated in 1970—now an eerie, grass-covered area on the coast east of Tripoli that was partly expropriated by the Soviet and then the Libyan air force and then bombed in the 1986 U.S. raid.

Driving over potholes in a small, cramped Nissan full of cigarette smoke, I thought, must explain the increasing fevers and occasional vomiting I was continuing to experience. Even when much of the abdominal pain suddenly went away, the brief respite gave way to even more sweats and fever. Or maybe the malaise was due to the newly allowed Al-Jazeera beaming in all the cafés, blaring out the usual monotony of IED explosions from Iraq and finger-shaking lectures from Gaza and Lebanon.

In due time I went aboard the ship and had my first dinner with the guests. Then I finished a formal lecture on the Roman economy and culture of the early empire in the lounge—and quite literally collapsed in a fever in my cabin.

A few hours after the lecture, I woke up, delirious, and called the ship’s doctor, a young Ukrainian. After a quick examination, she guessed a perforated appendix, perhaps already of some hours’ or even a day’s duration. She then explained the bad—and worse—options: The ship was embarking the next morning on a 30-hour cruise to Tunisia. If I did have a ruptured appendix, surgery would be impossible at sea. I could risk the voyage or, as she advised, try a Libyan hospital, although no Westerner to her knowledge had recently experienced surgery in the state-run hospitals. I had done some research on Libya and remembered coming across an old Wall Street Journal piece that referred in passing to Libya’s hospitals as “dirty death traps.”

By midnight, the fever had climbed higher, and there was really little choice. The Libyan minders arrived, worried that I had food poisoning or some other bad experience that might sour our once-happy plans for national conciliation. I was taken by taxi to the nearest Red Crescent clinic and rushed in. The on-call intern had good and bad news: The pain and swelling probably indicated a textbook case of a perforated appendix, so the diagnosis was not a problem. But there were a few hitches. I had to be operated on immediately at the clinic—no time for the hospital—and that would require finding a surgeon at 2 a.m.

The clinic was what one sees everywhere in the medical practice of the Third World. In the chaos, there seem no formal demarcations between patients and hordes of relatives, janitors, and doctors at work or between waiting and operating rooms. So I still insisted that the recurring pain was just another kidney stone or at least a year-old problem relieved, as in the past, by antibiotics. But on arrival, the bleary-eyed surgeon smiled at this pathetic denial and matter-of-factly announced his verdict: immediate surgery—the sooner the better, to ensure that the spread of peritonitis remained localized.

A Pakistani nurse sterilized a few surgical instruments, and soon a young Syrian anesthesiologist arrived. They took me to a tiny sparse room with a table and a light. The doctor assured me that he would not only do a good job but would also “clean up” the mess, with as many bags of saline and as much suctioning as necessary. He laughed at my final stab at alternative antibiotic treatment and murmured something like, “You probably want to live tomorrow, so we’d better start right now.”

I had a few memories in delirium of leaving a final phone message for my family back in California that things were not going well in Tripoli. When the nurse readied my mask, she said in English, “Put your trust in Allah.” For some reason—I am not a church attendee—I whispered back, “I prefer the redemptive power of Jesus Christ.” The last images I remember were of an illuminated minaret out the window and Gadhafi in sunglasses glaring down from the wall—and a strange sense of well-being that complete strangers, with few resources at their disposal, were eager to save my life at 4 a.m. in an Islamic clinic.

A PUZZLE FOR WASHINGTON

Libya poses a special damned-if-you-do/damned-if-you-don’t challenge for the Bush administration, especially now, after the Hamas election victory on the West Bank and amid the ongoing mayhem in Iraq, Afghanistan, and southern Lebanon, when neoconservative idealism is fading before the return of more hard-nosed realism in foreign policy. I heard the arguments of both sides in a later meeting with State Department and National Security Agency officials following my return.

Skeptics can’t really believe that Reagan’s “mad dog,” who once called on Arabs to “destroy” the United States and its Arab surrogates, could ever be sincere, much less relied on. But more important, how can the United States cut a deal that serves to legitimize a dictator and his gulag when Americans are dying in the Hindu Kush and the Sunni Triangle to foster and protect democracies?

And what about cutting the ground out from under Libyan exiles, idealists, and reformers—such as the outspoken Mohamed and Fathi El-Jahmi—long the targets of Gadhafi’s operatives? Isn’t this the Libya that tried at one time or another to overthrow or undermine the governments of Egypt, Chad, Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia? And aren’t journalists still locked up—or killed, as in the case of Daif al-Ghazai? And aren’t the infamous zina laws, which indefinitely lock up women accused of supposed moral laxity, still in effect, proving that in the Middle East a secular police state can be just as repressive as an Islamist patriarchy?

But so far, our principled distance from Libya has only facilitated Chinese, Russian, and now European entrance into the country, all of whom demand little of Libya in terms of democratization but take away a lot in business and oil. And who knows exactly the true nature of Libyan dissidents? Aren’t some of them radical Islamists, who want electoral victory merely to legitimize their anti-Western hatred? That possibility later hit home for me in an informal Washington, D.C., meeting, when one Libyan democratic “reformer” insisted in our conversation on using “Zionist entity” for Israel as he unleashed a repugnant torrent of anti-Semitic nonsense.

| The final bill for surgery, drugs, and a few days at the clinic was $800, not surprising in a socialist paradise where surgeons make about the same state-mandated wages as those who mop the floors. |

The arguments for normalization go on. The United States does not have a superfluity of friends in the Middle East, and the more wild cards in our hand the better, especially when we and the Libyans are shared targets of Islamic terrorists. To paraphrase the arguments of Jeane Kirkpatrick, sometimes isn’t it enough that a stable Middle East autocracy eradicates terrorism, because, unlike theocracies or communist states, such secular dictatorships are much more likely in the distant future to evolve into constitutional governments? So the conundrum continues.

AWAKE AND ALIVE

In the early dawn I awoke, groggy from the anesthetic but euphoric, since I was somewhat surprised to be alive. I was immediately told that the colonel “discourages” analgesics of any sort and that this abstinence was “good,” since I would heal quicker and avoid postoperative constipation. No matter—survival was good enough, especially if the antibiotics would kill off the peritonitis. The final bill for surgery, drugs, and a few days at the clinic was $800, not surprising in a socialist paradise where surgeons make about the same state-mandated wages as those who mop the floors.

The days of recuperation were the most interesting of my Libyan holiday, despite the pain from the surgery and the receding infection. The first guests were career diplomats from the American interest section. They were savvy, both married to Arab nationals, and the epitome of the U.S. Foreign Service’s best professionalism, insisting that food be served, that IV needles be fresh—and urging me to make plans to leave as soon as possible. Soon we talked of politics, and with characteristic sobriety they cautioned neither pessimism nor euphoria, but “exploration.” I liked them but did not envy their task in the next month of laying the foundations for an embassy ex nihilo.

Dr. Hafez al-Hafez, a Libyan-American exile and medical consultant for the American interest section, also visited regularly. He had only recently been reinvited into Libya as a neurosurgeon. Dr. Hafez immediately made sure that the peritonitis was in remission and that the right antibiotics were being dripped in, and then he held up my gangrenous appendix in a jar of alcohol. He smiled and said that I had had a close call. Then, like all Libyans, he talked politics.

If there is a future for Libya, it will require moderate and educated elites, such as Dr. Hafez, whom the government is cautiously inviting back in and whom it needs desperately to jump-start the economy and reestablish the beginnings of a stable, humane culture.

I also corresponded with a few Libyan government officials and, once back home, a few other exiles, and their similar optimism rests on the somewhat shaky proposition that if Libya’s vast petroleum and tourist potential is tapped, the resulting bounty will take on a life of its own, convincing even the revolutionary generation of 1969 that the Gulf model is preferable to the nightmare of Iran or Syria. Always in the background looms the untenable option of Al-Qaeda or the Muslim Brotherhood, which all want to avoid.

By its own volition, Libya appears ready to reenter at least the global commercial system and renounce its past roguery. No one knows quite why Gadhafi changed or whether the about-face is sincere, much less whether it bodes well for the United States.

I’m sure a desire for a Western standard of living, fear of ending up like the Taliban or the Husseins, jealousy of the rich oil-exporting Gulf sheikhdoms, worry over Islamists and former enemies in the Maghrib, weariness with foreign, money-hungry 1960s revolutionaries, the isolation of a crippling trade boycott, and the opportunity for more Machiavellian triangulation on a new world stage all played a role. But for now, the benefits for both sides outweigh the risks.

I lost my bottled, deflated, and black appendix on my return, when my physician thought its odd appearance suggested—if it really was an appendix and not part of the intestine, he wondered out loud—that it might well be cancerous. It was not, but the pathologist ground it up all the same. I remain very thankful to my friends in Tripoli, who saved my life and shed a great deal of light on a once-shadowy place, on a very memorable Libyan holiday.